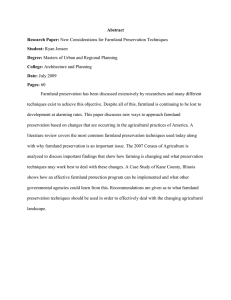

Balance: Lancaster County’s Tragedy

advertisement