Bush Versus Kerry: A Case Study of the 2004 Presidential Election

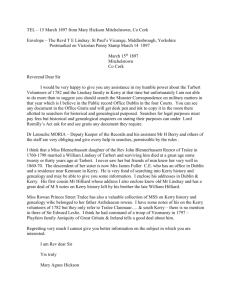

advertisement