&~4,~ Kilkelly's Heroes S.

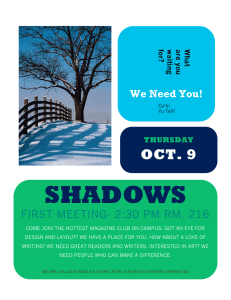

advertisement