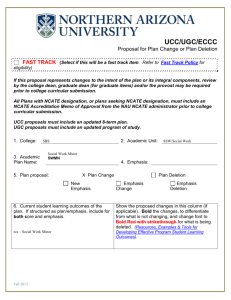

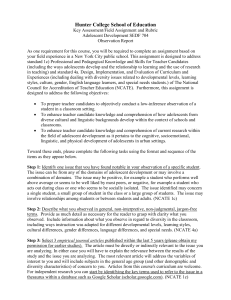

How Does Location Impact Meaning and Diversity Standard

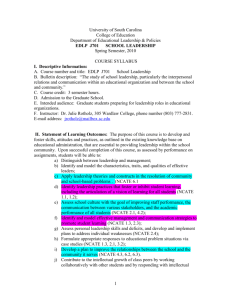

advertisement