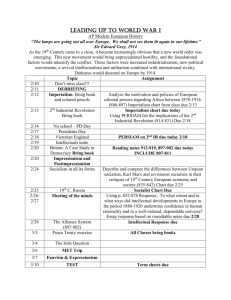

Not Really Failure: by Tamara Hamilton

advertisement