r 4-99,- BY

advertisement

r

SOCIOMETRY AND THE ELEMENTARY TEACHER

A RE3EARCH ,PAPER

SUBMITTED TO THE HONORS COUNCIL

FOR FULFILLMENT OF 'flIE R.&iUIREMENTS

OF I.D. 4-99,- SENIOR HONORS THESIS

BY

MaRY JANE CRONK

ADVISOR-DR. HELEN SORNSON

BALL STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE

MUNCIE, INDIANA

Jun, 1963

C)

PREFACE

This paper is b~ing submitted to the Honors Committee in order to

meet the requirements fOT graduating this June, 1963, on the Honors

Program. I began this paper in June of last summer. It is with a

great deal of relief and regret that I have now completed it almost

one year later.

I began searching for a subject in the broad field of guidance

in the elementary school. During the summer I did reading in this

area, and with the guidance of Dr. Sornson, I decided to write on the

area of sociometry. It was hard to decide on a specific area, since

everything I read was interesting to me. However, I think that sociometry

is one of the most important areas in the field of elementary guidance,

since many of the other areas seem to revolve around or hinge on

sociometry. Sociometry forms a good basis on which to base other

types of guidance activities.

I did student teaching during the fall quarter of this year in a

fifth grade classroom at Westview Elementary School in MunCie, Indiana.

~ critic teacher, Mrs. Irma Gale, and I carried out some action

research in the area of sociometry. I would like to thank ~~s. Gale

for her help, cooperation, patience, and understanding. Also, I

would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Helen Sornson. Without her t

this paper would not have been written. I also wish to thank my

friends for their underst~~ding and patience.

Mary Jane Cronk

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII..

IX.

X.

XI.

XII.

'1'tlJ1at Is Sociometry?

Why

~ocionetry?

PAGE

1

3

The :reacher: Her Judgment of Children and the Effect of'

Classroom Atmosphere on Children.

12

Setting Up The Sociometric Test.

16

Administering the Sociometric Test.

19

Plotting the Results of the Socioraetric Test.

21

Interpreting the Sociometric rest.

24

Using the Results of the Sociometric 'rest.

3~

Isolates--Stars.

35

Reliability and Validity of Sociometric Tests.

41

Action Research.

44

Conclusion.

56

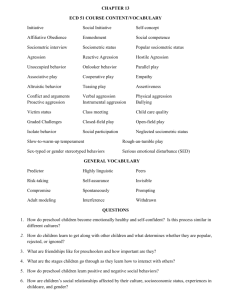

TABLE OF !I...ATRL,{ CHA.."'tTS

E,iGE

}IATRIX CHART NljUBER 1

-Who would you like to work with on a social studies

committee?

47

NA.TRIX CHART Wu}IDER 2

If you could sit next to anyone in the class you wanted to,

what five

peo~le

would you like to sit by?

54

lv1ATRIX CHART NUMBER 3

what five people in the classroom would you best like to work

witr. on a special project for the New England states?

58

!<IA.TRIX CF.ART NUMBER

Who do you

4

thi~~ ma~es

a good comT.ittee leader?

59

MATRIX CHART N1JMBER 5

What person in the room has some of the most unusual or

creative ideas?

},,~'flU'!c

60

CF.ii..RT NuNBER 6

·'.mat five people in this room would you invite to a

Halloween ?arty?

61

l'lATRIX CEAitT HL'MBER 7

\ihat ~erson in the rooo would you like to play with

after school?

63

TABLE OF FIGURE3

PAGE

FI,}URE NUI1BER 1

Sociometric Test Number 1

46

FI;VRE NliMBER 2

Sociogram

Who would you like to work with on a social studies

committee?

48

FIGURE NUNBER 3

Social Studies Committees

49

FIGURE NUMBE...tt 4

Sociometric Test Number 2

53

FIGURE l\"VHBE...tt 5

Seating Arrangements

55

FIGURE NUMBER 6

Target ~ociogra~

What five people in this room would you invite to a

Halloween Party?

62

SOCIOMETRY AND THE ELEMENTARY TEACHER

How important is the group in the classroomI

the teacher have on the group?

Wbat influence does

How is a sociogram helpful to the teacher"

Do the children need peer approval and acceptance in order to be secure

and to learn·,

These ar<::: some of the questions that this paper will

consider o

~ociometry,

the study of the inter-relationships among people, can

be very helpful in answering some of these questions.

If a teacher uses

the sociogram as a starting point in her understanding of children, then

she can understand her children better.

The sociogram points out rela-

tionships the teacher may not be aware of.

~he

can also use other

guidance techniques to better advantage.

In this paper, various sociometric techniques, tests, and sociograms are explored.

The value of sociometry to the elementary teacher,

how sociometry helps the teacher, and how the teacher can use the results

of sociometric devices in her classroom will be discussed.

1.

What Is 00ciometry?

Before going further, it is necessary to have a basic understanding

of what sociometry actually is and the terms used in this area.

sociometry is from the Latin word

II

"lhe word

socius" which means companion and the

Latin word "metrum" which means measure. l

Its literal meaning is to

lMarilyn G. Jones, The Use of 0ociometric Data and Observational

Records ~ Guides for J:TOniOt~ -;acial and InteIIe'CtuaI Growth of I'rimary

Children. Masters Thesis (Muncie, Indiana, Ball ,jtate Teachers College,

1955), p. 4.

"L:J-:J!1 1rte':;f.::·:~.r~~;T~}erlt

and

:?v.:~lv.~

t

'1

~on. n~

.:':ar:s: . ~.

~'.)(;rth·~f~1~r, ~·lOVir:"!1.~'-=:::c, :<'a,:; ~~t-t~;._J

~

ceiv"j

ot):

1.":"

e::: j";li'illing tb ~i.r n :~.,i:.:;» or'nlianc2.n2 t.h,'!i.r ;X~) :ri'c'n~;2. ;'J

1:ot

vc

behind th"?

rhoic-s.

':>"conr;

ditj on,

p. 11.

?

<-J:lcoh .:,.cr:mo, i,ho

l-iOUb'?, :!:ac., 1)53)>> p. Th.

~

,:·urviv;:;?,

""oronto

,

L.,vliffc)rd

':>ci

"~nc'3

~:".

:r·(~r3~·11ic~1.9

L~:·:s~·).'.·:.!'ch 1\s,:.~oci8t'.~!;,

the dtDaa1c aspect. ot interaction rather than on indi.14ual

children in ieolation from o.e another. tll The more one know.

about the relationenip8 of one peraOD to other people and hi.

environment and background. the better one is able to understand

this person. It 1. aomet1... hard to underetand the person in

isolation.

MaD7 terse are involve4 in the int.rpr~.i tation ot the sociogram. One of the.e is neglect.e. ~h. negl.ot •• is the individual

who receive. relative11 re. choice. on a eoCiometric test. A

reject •• receiv•• negative choice.. So.et1mes tb1. ie contu.ed

with the iaolat., but the isolate reoeiv.s no choice. either

pos1t1ve or negativ.. A sooiometric cliqu. i . a groyp which

g1ve. relatively fe. choice. o~taide ot the clo ••

knit group_

It i8 a subgroup within the l~rger group. When there is socio•• tric oleavage there i& a lack ot aociometrio choic •• between

two or aore subgroups. A star 1. a person who i . highly chose.

by the group, and a autual choice is the sttuation ot two people

cho.1ng each other.

8oc~o.etry 1. relativel, D.W.

Ita father was Jacob L. Moreno,

who wrote the tirst . . jor book on aocioeetl'1. ~ Shall ~!£vive? t

1n 1954. Although relatively ne., it bas become a very important

tool. Moreno oays that "80010.. tl7 bit" taqht U8 to recogllize

that human 80ciety 1s Dot a riga.nt ot the sind, but a powerful

r.ality ruled by • law and order of ita own, quite ditterent trom

uy law or order p.r.... ting otber part. of the UD1.er••• tt2

l,

II.

Whl Soeio.et£l?

Why should educators be conoerned w1th 80cio.etry? Aa haa

b.en prev10ualy said, aooioa.try ,can be very important in the

ele.entary achool. It. importanoe i. partially hinged on whether

the aChool i . subject •• tter ortented or pupil oriented. More

sohools toda.y are aore pupil oriented. "Iducatora have man,.

re.ponsibilities in common with the parente of their stUdents.

the,. aust help children learn to livo and work and play together

lJenninga, Socio. . trl!! Group Relat1oDa. p. 1,.

ZMor.no. !,ho Shall Surd•• ? t p. 92.

cooperatively as models for their future functioning in society.

They must aid children in achieVing maturity.

One indication

of an individual'. maturity is his relations to the other

members of the groups to which he belongs. tll

Other writers in the area of sociometry have pointed out

the role of the school in developing social responsibility as

well as helping children to learn facts.

Edson Caldwell has

said that "sociometry i8 derived from the developing attention

to the

sociali~at1on

responsibility of the school.

It has now

become an important tool in providing individual guidance for

children and in fostering a healthy classroom social climate. tt2

Mary Beauchamp and Boward Lane indicate that tithe significA.nt

role of the school is to

acce~t

children, to understand their

Circumstances, and upon this acceptance and understanding to

create an environment which complements the rest of their living.'"

It seems that educators are going to have to be concerned about

the individuals in the classroom and the

and amond them.

inter~ctions

between

This is just as important as teaching the

children reading, 'riting, and trithmetic.

Teachers need to

understand their pupils if "their pupils are to be motivated to

healthier personality and group development and to gain from

the school curriculum the most possible.,,4

The sociogram "can

reveal the workings of this child association and thereby help

the teacher to serve the student's needs and at the aame time

lDonald E. Guinouard and Joeeph F. Rychlak. "Personality

Correlates of Sociometric Popularity in Elementary School

Children," Personnel and Guidance Journal, XL (January, 1962),

p. 13.

-

2Edson Caldwell, Creating Better Social Climate in the

Classroom Through Sociometric Teehnigues (San Francisco:--'earon Publishers, 1959), p. 6.

3Mary Beauchamp and Howard Lane, Human Relations in Teaching I

Dynamics £1 Helping Children 2!2! (Englewood Cli!f;t

Prentice-Ball, Inc., 1955), p.i6.

!h!

_

4 Intergroup Education in Cooperating Schools, A Sociometric

Work ................

Guide, p. 5.

.

,

br1n, tbem w1tlU.n ran~"tI of the teacher-s educI)t10nal objeet1ve •• 1tl

"It 18 possible to affect the entire structure of the

group when individual relationships are i.proved. The applioat10n of soc1ometric technique. a.4 an understanding of the 1nfor. .t10D ga1ned permit the teacher to improve the soc1al structure

of a claasroom anti to raise the academic achieve •• nte of the

pupils to 80•• dogr.e. u2

Soc10metry and group dlnaaic. 6re 1nter-related. A person

i8 e.l wal& part of 80.e &roup in aoc1et1_ The ea.ring that "no

.an 18 an island" 18 beooming more true every 481_ the world

toda1 18 Yh'l inte:--depsndent.

Couoquent.ll. it 1. important

to learn to get alOftg with others. Moat people want to be a

part of a group and to bo ~cc.pted by their peers. The baby 1 •

• 'ael.f-centered being. Through group interaction d.oe8 h. learn

to think about other., to aooept 80c1al responsibility, aDd

become a 10 0d citisen. "Our a ••ooiationa with other human

beings are continto.ou.ly uking UII what we are becoming.'"

Humanness 18 learned..

Social acceptance is

very important to .oet people that

often, without it, they beoome maladjusted, unhappy 1ndividuals.

Mann haa said that "children who are socially Wlacceptab1e by

.0

their peers often exhibit eaot10n&11, unstable habit. that

affeot all areas of their develop.ent. If children can be helped

to acquire positive .oc1a1 a ••et., they - , become more socially

ace.ptabl~ to their ~.er..

Social aooeptance, in turn. &&1

increase their aoadem.1c aobiev... nt."lt- Social belongiAg i8 a

psyohological nec •••1tYI the cla•• room haa a profound etrect on

llntergroup Iducation in Cooperating School.,

wor) Qu1d.~. p. 1.

!

Sociometric

2Ieadora Hann, "A Teaeher'. ae.pona.1b111ty: UDderatanding

Grcup Behavior," EducatloD, LXXXI (Jov••ber, 1960), p. 17'.

'Beauchamp and Laae, &'·11 Sele" n •• J.Il "z•• claj • ."

P.lna.u.cs 2! He1pini Children Grow, p. 18.

4M.....U1 • ft. 'feaohert. ,Reapona1bil1t1l

Behavior,ft 1~. 17l.

....

Understanding Group

6

Children_ Hl

aelen Hall J.nning. baa a814 that "all learnia. in

80hool takes place within the .ettins of pupii-pupil relationship.. Teacher•• in ,eneral, r.alize that th. ind1Y1dual t s

p.r.onal and acad.mic crowth ~ be .It.cte4 a4•• r.ely or

la.orab17 b,. hi. ,o81tion ill the group aM that all pupil.

stimulate or thwart each other in "83 w."."2

Children have various Deeda tbat auat be met b.for. they

are r.a41 to oo-.1t th....l ••• wbolly to acadeale l.arnine.

Azoag thesG need. are the basic pbta1cal ...d. ot adequate nour1sb&ent~ eneiter, elothin8. re.t, and medical att.ntion.

The

p8ychological ne.d. are love, a le.llag of .ueo•••• and fr•• do.

troll .xe•••i •• tear. a..ide. tb_ •• n•• 4., th.re are aleo tbe

aeoial n.ed. of being re.pecte' aDd aocept.d ~y othere, belongiDg to a group, and being r.gar4e. aa worth while aa4 important.'

Beauchamp and Lane alao ba.e ad4ed the followiaC needs to tho._

alrea4y ._ntion_d--"self-re.pect &lul a De.d tor. freedoll 80 that

a person could make a mistake without it. bothering hi., could

expre.. upopuar id.... w1 thout becoll1ng UDpopular. and could

recognize a mistake aade by tbe t ••ch.r and .till fe.l .ecur.

with that teacher ... 4 "An tltUIiWiption badc to under_tandtng

human b.havior 18 that 8 • • r1 act is tor the purpose of sat1.,y1ng eo.. need."' a••d. are not alw., • •xpo.~4 to tull vi •••

"They never exiat in isolat1oa. t16 It 1_ the re.ponaib111t1 ot

lH11da Taba and othera. Di!IBo.1n, Huaaa aelation. B.eda

(Washington, D. e.1 ••erican COUDCil on !4ucat1oD, 1951), p.

2Jenn1n.a, Soc1oaetrl !! group a.latione, p. 1.

>Robert Oelau and Jack Kou,h, ".el1:l1nJf Children With

SpeCial Needs," T.aoh.r. Guidanc. BaaQOoOk, vol. 2 (ChicaSO;

Science Research .....oc1at•• , Ino•• 19"'. 1>- )20.

4...uchamp and Lane, Human Selat1ol18 in Toacbin" the

l)1umics 2! Helpin, Childrfln~. pp. i,2:r1tO.

5Dorothy Roger., Mental Health !!. Ele.. ntarl Uucat1on,

(Beeton. Boughton Miff11n Company; Caabridge I the it.ersid.

Pre 86 , 19.57), p. 22.

-

6 Ib1d •• p. 2!J.

71.

7

the teacher to look behind surface behavior to discover what

needs of the pupil are not being met.

Froehlich and Darley sud that whenever students come

together, they participate in a social interaction process. To

really understand a student, it is necessary to know the role

he plays in the group and his satiefaotion with that role. l

"Through the sociometric

technique

a teacher can find out what

.

.

reputations children have in the opinion of their peerst what

children in the group think of each other, and what preference.

and rejections pupils in a group have for each other. Much

information for understanding individual or group problems can

be obtained by pupils evaluating each other. tt2

In the socialization process of human beings, getting

along and being accepted by others is one of the major problems

of children. "The strength he (the child) finds in a group of

friendly peers serves the very necessary purpose of helping

wean him away from complete dependence upon his parents. As

the child learns at school how to relate olosely to others,

many of whom hold different values and opinions than his own,

he is developing some of the human relations skills that he

will need throughout all his adult life."3

A child •• self-concept is very important. The child who

is secure in his self-concept will have the confidence to do

things, to accept failure, to meet new people. and will usually

be interested in learning. "A child's estimation of his own

personal worth, his evaluation of his competence, and his senee

of personal superiority or inferiority are .haped. often to a

lrroehlich and Darley t Studyin~ ~.;tudent8. p. 327.

2Gertrude A. BOld, Understanding Children Through ,nfor~~!

Procedures (Laramie, ~h~ Curricul~m and Research Center, College

o! Ed1.4c:-.t1c,1l., Uni'{ ...·~lty of WyOll'l1ng, Vol. XI (No.1). 1957).

p. 20.

3Ed• on Caldwell, Qreat~i ,'tter QPciLL g*iUle J.A. lAt.

Cla••rAS8 %hrough lociometric "echpiqu••• p.O.

8

critical extent. by the statue accorded or refused hia by his

peers.

hen .. cM.ld fails to win belongi.ng or 1s acti"ely

rejected by his claseaate., the clas810al aSI"s•

or withdrawing patterns of beha"ior that usually follow frustration

are •• ea_"l Theretore, the rejeGted ohild doee not have an

adequate •• If-conoept. ae i8 usually 80 concerned with thie

self-ooncept and the relatioD of hi••• lf with his peera, that

he continuously does the wron& thing when be tries to win

api,roval. Often, this child i8 UDable to learn academic uterial because hi. Bind i . on other thing. wh1ch are of more

immediate importance and value to him.

Sinoe the cla.s i& • large group with various groupe contuned with.i.n it. it is inter•• ting t.o look at cohe.iven••• of

groupe. How much inflUence 40e. the individual have on the

group, and how much i8 the indiVidual attracted to the group?

"The power of a group may b••• asured by the attraotiven••• o~

.1".

the group for the m.mbo;....... ~

..... to l:eroon wants- to etay in a

group, he will be susceptible to influences coming from the

group, and he will be willing to conform to the rules ..'hich the

group .eta up.tt2 n(livea equal influence pr ••• ure., groups high

in attractiveness will have fewer deViated from a group standard

than will groups •• dium or low in attracti't'eneazh"' It ee.u

to be apparent that the stronger the ,roup coheeivene •• , the

more conformity there i8 within the group.

Educators alao h~v. to be concerned with .ental health and

maladjust.ent. It i8 often the person who i . not accepted by

bi. peer. or who does not accept hi. peer. who is having

lA~erican COUDcil of Education, The Staff of the DiVision

on Child Development and feacher Personnel. Be1pi!, 'taohers

Under.tand Ohildren (W•• b1ngton. D. C.I American Council on

Education, l§l5J. p. 219 •

...

ftramiC

'Dor"in Cartwright and Alvin Zander, Group

e.!!!

Reee!lch ~ IBferx. Second Edition, (EY&natoD.inoIs;

Elu'ord. New York, Row. I'at.rson, and Compa.nY', 1960), p. 250.

'Lester M. Libo, MtaaWJi GEoIP CoheGiven ••• (Ann Arbor:

R••earch Center tor Group Dynamic., I~oittut. for Social Research.

University of Michigan, 1953), p- ,.

9

adjustment problems.

"Mental health implies a satisfactory

relationship to one's self and to one's environment. as well as

the possession of problem-solving techniques for establishing a

satisfactory relationship between the two. nl "Children are considered to be poorly adjusted if their behs"vior interferes with

their learning. their personal growth and development. or the

lives of others. HZ

Kough and DeHa.n said that a sociometric

teot will help identify children with problems and will show how

the children in your group teel about their classmates and

friends. 3

By asking certain questions, such as Who Are They?

questions, the teacher

~an

identity aggressive and withdrawn

behavior and friendship.~

There are several main types of maladjustment.

The teacher

will probably see that some of her children exhibit 80me of these

kinds of behavior.

Bowever, it is important to remember that

"the difference between maladjusted children and most children

is one of degree rather than of kind.

That is, maladjusted

children have the same problems most children do--only much more

so.

~hey

are much more unhappy. much more self-centered, much

more fearful."5

Some children show an aggressive maladjustment

such as:

1. Doesn't go along gracefully with decisions of

teacher or group.

2. Is quarrelsome, fights often, gets mad easily.

3. Is a bully, picks on others.

4. Is resent£ul, defiant, rude, sullen, or apt to

Iteas" adults.

5. Disrupts cla8s and is difficult to manage.

lDorothy Rogers, Mental !lliene !! Elementary Education

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; Cambridge: The Riverside

Press, 1957), p. 15.

'Robert Deltaan and Jack K.ough, "Identifying Children With

Special Needs," Teachers Guidance Handbock, Vol. 1, (Chicago I

Science Research Associates, Inc., 1955), p. 58.

-

3Ibid' t p. 63.

-

4Ibid •• p. 65.

5DeHaan and Kough, "Identifying Children With Special Needs i t •

p. 119.

10

6.

1.

8.

9.

Is regarded 01 other children a8 a pest. Rub.

others the ""rong .a1. Ie exoluded -1 others ..hene.er they get the chanoe.

otten steala.

Lie. frequentl,_

Ooca.1onally 1. deetruct1.e ot property.l

others ex.b1b1t viithdr••" aaladjust•• nt .1to such traits as the

following:

2..

Is not not1ced by other cbildren. Ia neither

acti ••ly liked nor d1sl1ked--juet l.tt out.

Is one or more of tbe tollow1ag: ahy. t~dt

fearful, anxious, excessively quiet, tenae.

Daydr •••• a gre.t

Bever atends up for him.ell or his 1de.le.

la "too 1004'1 for hia own good.

rinde 1t diffioult to be 1n group aet1vit1es or

to be relax.d when with othera.

X. easill upaet, feeling. are readily hurt. 1e

ea.111 diecoura,ed. 2

,.al.

Other chtldrea aa1 ahow sympto. . ot general aaladjust•• nt such

&a1

2.

.h

2

Ne.ds an unusual .-oURt ot prodding to cet work

Gompleted.

ta 1nattent~.a and 1ndifferent. or apparently lazy.

Exhibits n.rYO"8 _neri ... eueh a8 nail b1tlnth

sucking thua~ or fingers. stutt&ra. extreme ~.Gt­

la.en.se, musole twitching, hair twisting, picking

and eoratabi ••• "eap u4 frequent eish1ng.

Is aetivel,. exolud,d _1 moat of tb. children wheneYer they get • chanee.

I. a failure in .ohool for DO partioular reaeon.

Ia aba.nt from school frequently or dislikes .cho~l

inteneel,..

Se ... to be aore unhappy than 808t of the ch1ldran.

Aohie.e. m~ch le •• in sohool than hi. ability

iadieat.d he ahould.

,

Is jealous or o•• reoapetitiye.

Ib14 •• p. 61.

-

'Xt.J.cl., p. 62.

11

116c.J th bdoL.

~

.1.•

Cli'

i:,e~ll

(:!,t<r.. tb.l llc~d..-l t t

Chilarc~ wit~ sound &Gotion'

-<-able to _,cc.e;;t ttl"..:. ,,1', .';

the,'u3rC,lv,,' •.:'. \!1ey ecti;!lote t \~~d:" "::,i.c:'!;~' rc;s..li~,tic l:~<., h,:,vin

n,;it,el' teo ::i [, J'!" t·;.: 1. C," LL

~,

\,,1

i:o.U€FE;nc~er;t

ir c:eci·:in:,. thi!' ..

Df th~ G ...

'rlhey ar~:" cOl,ficj.Ent nf trJci.:C t.jl;:_li

5i tuatioE .. to'. [, ·'d'., ceil,col t tr.,

chilJr~n

other

..?

4.

Ths

1

-.>~

gu~ltQ

5.

:r.ct co:";.)t.~~ntly iJ.11 -.:ctt.-J. \:;lt

'The,)"" a.T'>.;

feeli:-:

~.)i

at le,,;.(::·t

<)

l""

~~~r.~~

O":E

,;..;,n::·~.-·r,

tn(:J

trUE:t

clu:~:,

~heJ

co~ci~er

~:'rcuT;

•

tie

They

~ccent re0~o~aulc

(-j.

'l'he~.:--

'7.

grou~

r~·:

to

(~~x:~,~,

1

l~~..

,.1(2

:.~::."'~-!

3:"-:

',

..

·.',·or'::""~/,

r·l:>r

.'....I-~

or

r~·. . :dX(~\~.

to

i.ur~·.

lrie~!rJ.

so~e

t}lt:~

je-:.::JloUf-j:,'· t

SE:;al~!

ct~~

like

They

feel

u.

the

~"e~<L~

Ge~'-.(.~·;-).ll"\

lik. e

t

to

t.','

if.!. te rc

responsibilit~

tje"8e]v~

:.: t~:

ler t~

i nt

:~:.n

T~.~l

. . ..,: r t

t,'.::~.

Oi

rc~~on~i~llit~.

i:... ~'rcve their ,-,bil.j_ti.ec, ~:.··:.,llGt

2:.nd f:iee n(-::\. e:~},erJ..cricc':-;: e:,: crl.~!.

cJnj

L(,

.c·r

t~::le.),~t~ t

~

(.1.

in i .. : . covir:

relaticnG~i:6.

tc.c~ l.'

r

7i vinrS

1"0

1. "C'2C

tv 1.f .rn.

t

'y

..','

, ';1..:'-..

1;_

C ::' 1'1

.i..·:;,"'r

C " . r:

. 1. \;

::':

_~!.

/.;

" j

v:

.0','.,

,

V~

t,

l.

.:1

.,

...

;~

i,. ,- ~ .;

~

t·,

">"'~"~"~

._ '_..i-

' .... ,'

\

:.1- ::.

........

i •. " "

"

t

i. .........

\..L ..

(,

..........

r~

..~

:.. _~ 1,

t

c:r ..

,-.

c- ;

t

.'.

t: (l

Y'

,i C~

>_'...1.; ....',1

l. ::: .

.-~.

.

,-

,

"

~c

'I;

2. ri 1. .

(:0) "

:1:

-

it

i.-",,:

oi

'.,

.' (~

~

1.

..

•

J1..L

t

J0.,.'.

,.,

~. . : . {_

vi'

:

.K. ''''

,~

. • J,

...

---------_.._.,

~

J •

)

,

•

--.)

.

-;,....~

(,;

-,_.i-·.;;"

"

of

;..:.

hOUT6

clwlogy COt.:rf.r'L,

te . . ~t'1tt~rt u.1?'> :~,~~i:;:t~~

contu:~t

'.1. t./'. th.e

h.~~ v ';;.'

"'_:":' ~'?~

':)i

't ..i

c!.~: :~,o

....

"

/

.'

.

.

~ t~~<,",-J..L:.

.~ ~~

lli0~t~

IQC1,~,~

Dr

:cor'-': .':''',

:,..:

jv.<i

L

c.. :.,

..:;

tr~c

'

,) i.

...

,

v\. ..

j Ll, j

€

1:

D.'

tLv~ir

ecr:t,,;., "

,

,

l:

. t;:-

c.

O'::"'..A:C.;.~·l

,'.' ..

t ":

t ) I,

<,0

~.i.'

'; ", (: ,'C'

t (.

t.

c: ",

1

..

"

~I

~. ~.11

.~ t

.~ 1 !.: ,

: .i1.1

1.':,:,1; :,(·:1

-_.

to _

" 0

i

t

,- l:.

r', "

,

.

V" I'~:

~ ... ~._ ,.: j 1

.! .

1. l'

C "

l

•. j

the

.,-~

r t.)

.

y~:

....; .'

~

-..:: :'.... 1 'I::.

, .--~

t; "',

t

:;

.i...s- •

'"'>i:',i.:~L_Lo

1,-

... ~

]

,.,

L ..

t

0:;'

t

::

, ".

.~

l.n

..t '

tt

'.: 1 .....

'" !'

fl'\~f:::r

.... '

",-, •.

i.,.

r

<.... '

~.'

.,.i 1

r~~n.

C.: .

0

•

,(

cnc·.,,) 1 ,'1

Ci;'.

t

;-~c

1 i~

r:.J.,

)

..

..I':

Cl' ,:.<1':

~

-.--~

. I

h

:·li::",-rl:~ t

.;_'i' v_~:)r,t'

.~..' c:

•

,J

L

•

LJ +-

.

\.

)

to

,

,

,'-

(':. .1:n

~

.Lf: 'l'"n

T,

, (~

n <..

c i _...L ( n "

.

t • -,"

flU

,

"

r"i_

r'rinc:i. (,le

L

t,

t,;-"

V(';r j

;," ur

t

r.

1 '.

",!:':i. ;,",

; ,

,',.::."

l)j

t·

t·ne.

•. J. • .",

•.,t:,; \._'"-

',;: ,~

1~

. :'. Xl.

_"""",::c-

,-

.;.

' ..>

,

.

.--...

~,;,

'.l

...~--.- ..

t,

i,"

-------"'"

~;

10

.:rovide tlc' .-;t.i.loren ':,it;·

IV.

UF thc

~ettin~

cleci'"jes

s~e

~ocio~etrlc

iSbt.

.·:~nt

taoY.: that .-:iJ.n

tne

c1 ...'.;,:::: roo:....

tJ. '.'

i~tic

6itu~tioLC.

cbiloren.

be

C

import~nt

&~~

~ill

Licly.

ferent

''''rviU·

1

.~-' 'IA.

~'e

L)

<,

t..... •

·,3

.lYi

----------------------..)

r:... ";"':...:."'...:, L~

:7'."!: 1,1

oe useO.

.nin

t

... C-!';:: ,..

l

, II

'" :l

J. • •

•

...

.

l

"

."

I

\

•

..

.

..:...

(:, ,r.

,t:

jl\ . .!..i..~'lt-b-".:"

G,:':"11 C

V,:

r ._

,J

....>

.'::.~

(':.

.l ..

. .

....

~~

... '

~

I I .

t ;..'-

.... -~~\..1

t

~j G

t ,..I,i'e."-

.-

; ,(..'

.,.,'

·,·.d

f-:

L

:...,,,

t ."

1\,.;,

I'Ot:...

U; ·f

:'.:1. t

1. .,

..

'

i L"

.

, ::,:. t!

u ,.:. t i c-' ,;

.

.;

01.'

.~

.',

..

~"

,.

...

.....

.

;/

,-'

~J

t•

.'

..

J •

.::..

"J.. -:.

.'.

~

r:

')' t

, 01

t - .....

,l'Cj

~--,------

1

.::;'

..

'\

-"-':'--~-.....

'

T ,,'i.. ; •

i

"l"r'

5,

I".

':

'

o

. t

.. .

!'

(

..

IL

.~

It

i'~-...:.t .. t,r;.~c. /l":

+;" '._'J_

__ "",1J. ..

j·/..)·A ......

,.,i.

-:i;;';'u

~:.o.':.,t

,.~.;

it:'

.

.

... ..... ',' .....

1 • "

••

-;.. .'

+ ,

•

~

~

',',

J..,

C. L C l~ ({

1: .~.

t

~.~ 7"::

r

lr,:

lCulCi'iell,

.';rl'~tin'

Lcttc·r

~Inro1.~S'~ ;?_22io'':i~"tr::.c.i.(:;c:;.T:.~. lh.'::O,

}\'!

'~~.

:' .•

~,ocici

,:.

1J.

:2 I I ,

------_..&.

:.·.. J_~~£l-.... ·-.ri ~~~JC~:.:~ G.~n\l

l' ~), p. l)t

't

3rC'[LLUr.. .

pp. '"tU-'+/.

01.

'~~<o.,rOOt_

-------

1:;

this Ce,Se

h.:-~

tlH; I.lm; hasif! if'! on the' chooser' !.in.> the

t

gives to

student to

iii

mc.~;te

of t:hoices

than th(· numb"!,, of ehoiceB he receives

oth~rs rat~lt:rr

from other.s.t.ccordintJ: to John Burr, "it

allow

11umb~.r

:.1,,1

;u.:,r.y choices

<H;

IW&t

St1tJl'U5

effective to

he aeeires on c_.l.:h

qUb't'-

choosinz ffitny Dr f~~ clu6smataB. be

1

reveals information about himself."

"Such information i19 u6eful

In the very fact

tion.

01

in evaluating the individual's desire and drive for social intaraction.,,2

Mary I .• Northway sugGe sts usinf~ three criteria and. three

choices.

By using thCt same number of criteria and choicetl. the

sociometric resul t~, are more dil'ectly

equat~,-n8:.3

cOr?i~.relble

wi thcut statistical

Gronlund aloo \:.>"'-ys that a fixed number has statistical

and practical advantae;ea ..... the number beinE: influenced pE.rtly by the

age of

subject6 but mainly by the stability of the Bociometric

th~

re::oalto.

Nursery SChool and kinder/,arten child.ren have little

ability to aiscriminate beyond first choico.

In the early elementary

yeeJ"s there should be three choices for each criterion.

Frorn the

third gralie on, five choices can be made without difficulty.

Gron-

lund. also .bays that studien have shoY-,n thut five choices provide

the moet stable aociotnetric results. 4

In sur.llilary, to set up a t::ociometric teLt the te,_cner must

decide hoYt many questione and how many choices ahe v/ant:s to use.

Jl.lso, she needs u purpose behind h<'::r queotions

be real a~d have meanini for th3 children.

60

that they will

dnce she has the teat

set uP. she is then rehdy to ad:d.nister the test to her ola6oroom.

V.

Ad:ninistering the

0hen a

teach~r

decides to give & bociometric test to her class,

it it:; im90rtant that she have an

children. til! the

Test.

SOciol~etr.ie

teactl~r

eut.~"bli6hed

ru.pport with the

-haa alrel,dy gained a ,{oed working

lnarr, .:f.!!!. £lementary Teacher

.!E.2.

Guidance. p. 150.

2aronlund, bociometrl ~ ~ Classroom, p. 46 •

.3NorthvJay.

40ronlund,

.2! ~ocioll1etry t p. ~.

Sociometry !E !h! Classroom, p. 48.

!i

Primer

20

relationehip with the clas8. the resulte are likely to be more

vaLtd. n1 The atmosphere of the clas.rooa will affect tn. responses

to III sociometric test.

Do not «ive the eoeio•• tric test until the group has been

together from four to six wee!.ua. 2 The opportu.nity the children

h~ve to. know each other affects th~ re8pon~e8.

The children should

undex-'stand why the test is being given end wh1 the? should answer

the que'at1on6. '2h. instruct:ions shOUld b(j clear. The aneVier.

should be confidential. Only the teacher shOUld see them. The

ehiidren should be assured of th1~ before they begin. Be aure the

children understand that the;y /lay write the n.ame of any boy or girl.

The whole procedure ehould 'be as casua.l as poee1ble. "'the

queations should be pre~ent.d in an infora~l and natural manner-that itl. in such a .a.y that it dQel'S not ta'te on undue importance."3

Preeentthe teet '11th interest and some enthueiasm. It ia alao

good to aay hOl\! scon the e.rranf:.ement~ baaed 'on the test can 'be made.

Every blank should be filled unless the child absolutely feels he

can't or doesn't want to. 4

If the teet is being given to a class below "the fourth grade,

give the te$t to each child indiv1d~ally and record the answers for

}I..1m. G1 ve 1 t to the whole group wi thin 8.& shor t fA time a8 l;O$slble

80 chance for discussion is le&aened.5 ~~en giving the teet to the

wh.ole group attbe 8ame time. usually five minutes is enough time

for the ch1.ldren to make te.e:!.r eho:1.cea.

So. . t1.mes the tec:.cher might want to use .. suceeauye 80c1og1'&m

in order ,to di~gnol)e the effect ot changing rules and arrangements.

A successive sociogram i8 ~ aooi08r&= given after the firl~t sociogram ..a a follow-up. nThe cb:1et Vill.1U$ of 8uocessive 8oeiograms

lJarr,

1!:!!.

El"Blentul t.acher ted GSd.a.llce. p. l~.

2 Taba and other •• ,D1.al.noaipi

ii;tm.a.!

1iel.. t~.o,u N.ede, p. 16.

'rroehlloh &.nd Uarley. St!l!bJI!I stUdents. p. 330.

4Northway, ~ frf~~: !! Soc1oa. trl. pp. 6-7.

-

5 Ibid •• pp. ,5-6.

\

21

lies in their emphasis on the degree of stability within the

structure as a whole and on the relative slowness with which membere alter the feeling they have about

Olle

another."l

"The use of

successive sociograms gives individuals continuing opportunity to

exercise choice and to learn to act in their own behalf and to livee

by their decisions.,,2

If a second sociometric test is given. it

should be given after a time interval long enougb to make sense to

the group members--to justify it from their point of view.

For

children up to the third grade, wait four or five weeks; for fourth.

fifth, and sixth grade children, wait six vleeks. 3

VI.

Plotting the Results of the Sociometric Test.

Once the teacher hae given the

to know what to do with the results.

sociomet~ic

teet, then she has

These results have to be

plotted and interpreted before they can be of help to her.

the first things to do is to make a matrix chart.

given on page47'

One of

An example is

On the matrix chart the choices of the entire

class are tabulated.

The names of the pupils are listed in the

same order vertically and horizontally.

Then the choice and the

number of the choice are inserted in the proper sfluare to indicate

which choice is given.

At the bottom of the vertical column the

choices for each individual can be tabulated.

Add together the

choices from all the criterion and the result is the 60cial acceptance score or choice-status or

socio~etric

status.

Count the number

of different people who have chosen an individual and

the column of "number choosing."

en~er

this in

This is the sociul receptiveness

Bcore. 4 Count thE: number of different individuals whom the indiVidual

has chosen by counting the entries in the horizontal column.

this number under "number chosen."

This is the emotional expansion

lJennings, Sociometry ~ Group Relations, p. 47.

2 Ibid., p. 4.5.

3~.,

Enter

4.5.

4Northway, ! Primer £! Sociometry,

p.

p. 8.

22

Bcore. 1 It 10 also belpful to draw a diagonal 11ne from the upper

left-hand corner of the table to the lower rl,ht-hand corner. The

main purpose of tbiB i~ to 5~rv. a8 ~ guide ia ident1f7ing mutual

choic ••• 2 ~nia matrix chart will be helpful if the teacher chooses

to p~ot her results in another way.

The most comaon way to show the results or a sociometric t.st

i8 the 8oeio!p"am. This 1.e fl ltiap''' .hovae; the relationships

among a group of people ... n"ho onoae who,.." An example ot a 8Ociogram may be founci on pa~e4b. When plotting a SOCiogram, firet

decide 011 the symbols that are going to be useu. aeneI'ally Circles

are u.ed to represent girls and triangle-a tor bOYG. The IUU4. of

each pu.pil shou.ld be printed in full inside the 5;ymco1. Place the

girls on one Bide 01' the eb/irt and the boy. on the other. The

eyabols nearest the center should be used for frequently chosen

children. The Bymbols neare.t the. should b. for mutual choices.

The most distant symbols should repreeent children who have received

few or no oho1eee. To 8ho'6' one-way choices, si,."'!lply draw (:IJl arrow

from the chooser ;oint.1ng to the chosen peraon (--;.). A autual

choice 1e ehown with a line touching both .ymbole and a small

vertical bar at the center (~). A dotted 8ymbol 1s u$ed for

1\

&n.y person that 1s ab.ent the day the t.et 18 given ( :... ~ ). It

lIO_one is chosen outside the group, the situation 1s ind1c~ted in

the same way as for an unreoiprocated choice and a dotted symbol

should be drawl!. :1.11. 'Ihe connectin, linllt chould be left open eo

that an arro~ or a completed joining can be made later it the child's

ohoices becom. kno~n.3 It rejection questions arc ueed, plot these

the same way using a dirterent color.

Another way of sho_in, 8001al relationships obtained from

sociometrio testing is the target diagram. An example oan be found

in the az>penJ1x on pag~ 62.

~

target diagram.

I

M4ry L. Northway is an authority on the

target diagram contains tour concentric circles

..

lNerthway, ~ l~i~r £! hooia •• tEl. p. 9.

2aronlund, ~~~••etrl!ala! C~a8.roo~. p.

,8.

'Intergroup Lducatio!l in Cooperating .;3chools.

Work Guidv. p. 26.

!!

soc;oetr1c

23

thpt

~re

an equAl distance

center for

<1

sep~ration

~p~rt.

A vertic2l line is

of boys Imd girls.

dr~wn

through the

The numbers on each circle

indic~te the choice levels for each of the concentric circles. l

people with the highest scores

from each

choice.

rocpted.

individu~l

~re

ne?r the center.

An

~rrow

The

is drawn

to the person to whom he gives his higheft composite

A double arrow is drawn if the subjectts hiphest choice is recip2

"When the sociogram is plotted on this diagram the sociometric

status of

jnn;v;rlu~l

group is depicted."3

group members as well as the social structure of the

Northway has listed two important points or safe-

guards to remember when using the

t~rget

sociogrcm:

It is an abstraction--b,r depicting only dominating choices

(or else resulting in confusion), it is a further abstraction

from the living situation.

It is as.y.mbol. It is properly supposed that a higher

sociometric score, reflected in position of nearness to the

center of the target, is directly rglated to values of good

mental health. This is not proven.

1.

2.

The rainbow sociogram is a half-target sociogram with some additional

features.

It allows for the measurement of many factors and many individuals.

No other device is so helpful in detecting changes over a long period of

time.

This diagram can be read outwardly from the center out or inwardly.

The rainbow diagram does not show the intricate network of individual

choices.

Rather it shows the relative position of students in the class.'

IGronlund, Sociomet;r in ~ Classroom, p. 69.

2'Moreno, The Sociometry Reader, p. 224.

3Gronl1.md, Sociometry in

!:.!:!!!.

Classroom, p. 69.

4Moreno, The SOCiometry Reader, p. 227.

'Caldwell, Creating Better Social Cl~te in ~ Classroom Through

Sociometric Techniques, pp 25-29.

24

It is 'possible

t~

show the results of sociometric tests in many

ways. There are many ways that have not even been mentioned in this

paper.

However, I have tried to give the most common and the promary

ways of using the results so that they can be interpreted and put to use

by the teacher.

VII.

Interpreting the

~ociometric

Test.

Now that the teacher has plotted or shown the results of the sociometric test in some way, she needs to know how to interpret these results.

The sociogram only points out the relationships; it does not explain them.

"Interpretation involves attempting to account for the patterns that the

sociogram reveals."l

It is important to remember that "even the least

accepted is liked by someone, and the best accepted not liked by someone."2

So be cautious in interpreting sociograms.

To read the sociogram,concentrate on. one person and follow all the

likes t.hat lead from and to him.

plete~

If these patterns of relation are com-

self-contained with no arrows or lines

friendship is a clique.)

rmL~ing

between them, the

Note the pairs or mutual choices.

to see who the leaders or stars are.

named by several other children.

Also, look

These are the children who are

If there is a s.ymbol with no lines

leading to it, then this person probably is an isolate.

The most frequent

pattern in the youngest grades is a chain or string of one-way choices.

This is because younger children are "not consciously aware of the impression

they make on others.

Being reciprocated does not have importancA

lRogers, MAntal ~ene ~- -2'ClD'lnir'''''

~~-

25

the child is still self-centered.

Little children do not know much about

each other's feelings--one of their big problems is adjusting to others. ,,1

Sometimes the teacher is very surprised because certein children are

highly chosen or overlooked that few adults would have predicted. 2 Sometimes opposites or likes mark each other. 3

The teacher should also check the cliques or subgroups to see if

there are few lines or choices between the different subgroups.

be a sociometric cleavage among groups.

for this cleavage.

Sex, race, or religion may account

Usually there is a cleavage in sex.

girls prefer members of their own sex.

There may

Most boys and

The lowest percentage of cross-sex

choices appeared in the play companion criterion at all grade levels. 4

M8ny choice lines occur between boys and girls in kindergarten and the

first grade.

grpdes.

After this there is a decline into the fifth and sixth

The number of choices then remains fairly constant until the

eighth grade.

After that the trend is reversed.'

In the fifth and sixth

grades linked chains of mutual association become more constant, and there

is a strong tendency for homogeneous groups to appear. 6

When the teacher is interpreting a sociogram and sociometric scores,

it is important to keep in mind the fact that sociometric status obtained

in the usual groups is not related to I. Q., M. A., or C. A.; it is slightly

related to skills when these are important to the group and to measures

1

Intergroup Education in Cooperating Schools, A ~ociometric Work

Guide, p. 45.

2Jennings, Sociometry in Group Relations, p. 21.

3Ibid ., p. 28.

4Gronlund, Sociometry in the Classroom, p. 112.

'Jennings, SOCiometry in Group Relations, p.

6

Ibid., p. 75.

15.

26

of social adjustment and

p~rticipation.

Also, sociometric status is an

index of the degree to which an individual conforms to the folkways and

embodies the vp1ues of the group; it is not as close a measure of his

inner psychological security.1

Jennings has listed the following questions

that the teacher may ask herself when analyzing a sociogram:

l!

2.

3.

What appears that you had expected would appear?

What appears that you had not expected to appear?

What seems to account for certain pupils being the most

chosen and receiving few, if any, rejections?

4. What seems to account for certain pupils being unchosen

or receiving many rejections?

S. What seems to account for the mutual choices?

6. What seems to account for the mutual rejections?

7. Can you think of any classroom arrangements which may

account for the above choices or rejections?

8. Can you think of any classroom arrangements which might be

a factor in the general patterning of the sociogram?

9. What cle~vages appear in the sociogram? Absences of

choices between individuals related to a group factor.

10 0 Can you see any spots in the structure of the group as a

whole that need to be more closely related to the rest of

the group for better mors1e? "

11. In the light of your analysis of their inter-relation

structure, wh~t understandings and skills do you estimate

the pupils have already developed? Which do you estimate

they need to develop further?

12. What do the majority of most-chosen children have in

common?

13. What do the unchosen ~nd rejected children have in

common?

14. Are there visible signs of segmentalization in your community--association patterns which divide according to

race, religion, residence location, or any other factor?2'

Looking at the over-all pattern of a sociogram, one can see that

there is an uneven distribution of sociometric scores.

The tendency for

a larger percentage of pupils to appear in the low sociometric status

categories than in the high status categories has been shown to occur at

all age levels over different sociometric criteria, among both sexes,

and with varying numbers of sociometric choices •. When an increased

./

INorlhway, ~ Primer of Sociometry, pp. 30-3h

2

Jennings, SOCiometry in Group Relations, pp. 31-32.

27

number of sociometric choices is

m~de

pvailable to a group, there is a

tendency for the largest number of choices to continue to go to the

group members with high sociometric status while those with low sociometric

status continue to receive a disproportionately smpll

Shifts in sociometric status

positions.

~re

sh~re

of the choices.

1

relatively rare at the extreme sociometric

"This would tend to indicate that the high and low sociometric

status positions are more stable

th~n

those in the

aver~ge

categories and thus can be used with greater confidence. ,,2

sociometric

These facts

have been incorporated by Moreno into his sociodynamic law which indicates

that "the lIDeven distribution of

lIDeven distribution of

we~l th

socioill~G.c;;'c

in a society.

choicEi5 is

Sillli.li'ir

to the

Thus, few are "sociometrically

wealthy" but many are " sociometrically poor. 1t3

In interpreting the sociogram, the teacher needs to find out the

patterns in the

sociog~m

and the repsons behind them.

I~his

interrelat-

edness of human beings is viewed as the very foundation of human society.

The choices of children, then, take on new importance.

drawn to certain people because they see

personal appeal.

choose a

tr~its

Children feel

in them which have a

As noted on previous sociograms, the isolate tends to

st~'!I"'-he seems to sense thAt this person can help him. ,,4 "Socio-

metric findings show that individuals tend to form two kinds pf groups

in which different needs are paramount:

(1) groups in which the indi-

vidual as a person receives sustenance, recognition, approval, and apprecbtion for just being "himself"; (2) groups in which the individual f s

lGronlund, Sociometry in the Classroom, p. 111.

2Ibid., p. 131.

3Ibid., p. 95.

4Caldwell, Crepting Better Social Climate in the Classroom Through

Sociometric Techniques, p. 40.

26

efforts

~nd

ideals p-re focused

tow~rd

objectives which are not his

~lone

but represent the fulfilling of goals which a number of individuals agree

to seek."l The st~bility and cohesion of groups is determined by the

quantity of pairs and the interlocking between them and not the high or

low number of unchosen.

2

Sometimes children choose others because of a combination of emotional

and specific helpfulness which the chooser expects from the individual he

has np-med. 3 Sometimes the children know their needs better than the

teacher does.

Sometimes children

ence or problem.

~re

brought together by a common experi-

4 Children's responses are limited and modified by the

community social structure, the family responses they have had, their

residenti~l

proximity to other children, and social cleavages existing in

the community.

Sociometric results in some of these areas suggest that

the sociometric results reflect the social pattern in the community.'

Residential proximity has the greatest influence on children's actual

friendships.

In choosing desired associates, the influence of residential

proximity is minimized.

6 Usually children who are highly chosen by their

peers tend to be more intelligent, to have higher scholastic achievement,

to be younger in age, to have greater social and athletic skill, to participat.e more frequently in sports and special activities, to have a more

pleasant physical appearance, to have

mO~9

social and heterosexual

~reno, The Sociomet!l Read~, p. 87.

2Moreno, Who Shall Survive?, p. 132.

3Jennings, Sociometry in Group Relations, p. 72.

4Ibid., p. 73.

'Gronlund, Sociomet~ in the Classroom, p. 222.

6Ibid., p. 223.

29

interests, and to have more need-satisfying personality traits and

characteristics than children who receive few or no sociometric choices. l

In interpreting the sociometric scores, the "gross sociometric

status may be interpreted as an indication of the individual's external

social adjustment to the values of the particular group, but that it does

not reflect directly his degree of inner psychological security.,,2

It

is an "index of the degree to which he attempts to conform to and abet the

group's folkways and mores; in this sense it is a

towards external social adjustment. ,,3

me~sure

of his drive

It is suspected thpt there is a

tendency for an individual's sociometric status in one group to be positively related to his status in another similar group.

likes or dislikes

hL~,

4 If one group

then another group of similar people would prob-

ably tend to like or dislike him, also.

Norman E. Gronlund has listed some common errors that teachers make

in interpreting the sociogram.

1.

2.

3.

4.

These errors are:

A tendency to consider the socbl relations depicted as

actual relations among group members. Since the sociometric

test measures underlying social structure, this is neither

desirable or true.

The sociogram is sometimes viewed as a complete picture of

the social structure of the group. However, sociometric

criteria are limited, etc.

A network of choice patterns are frequently thought of as

representing a fixed group structure rather than a picture

of a changing social process.

The social structure depicted in the sociogram will look

5

slightly different when constructed by different individuals.

lGronlund, SOCiometry in the Classroom, pp. 221-222.

ZNorthway,

!

Primer of Sociometry:, p. 30.

3Ibid., p. 29.

4Ibid ., p. 28.

'Gronlund, Sociometry ~ the Classroom, p. 77.

30

Knowing how to read the sociogram, the common patterns in the

sociogram, and reasons behind some of the choices, is not enough to know

when the teacher is interpreting

t.hA

sociogram.

"The value of sociometric

testing, as in any testing program, lies in the interpretation and use of

the results.

The conclusions drawn and recommendations made from socio-

metric testldata necessarily are subjective.

The soundness of the con-

clusions depends to a great extent upon the teacher's skill in obtaining

additional information about his pupils from other tests, health records,

interviews with pupils and parents, and observation.

An

under~+'pnding

of

children, their motivations and prestige values, plus the ability to determine the causes of pupil behavior, are some of the skills needed to interpret sociometric data effectively."l The teacher needs to know something

about where the students live,

~omething

of their present situation and

background, local customs, and traditions of the school and community.

When the teacher has done an adequate job of interpretation and knows and

understands her children and their interrelationships, then she is ready

to put these results into active use.

VIII.

Using Results of the Sociometric Test.

The most important part of sociometry is putting the results of the

test into use.

This is the main purpose in giving the sociometric test--

as a guide or tool in helping the te?cher work with her class.

There is

no value in giving a sociometric test unless something is done with what

the teacher has learned from the test.

The sociometric test is valuable

to the teacher in helping her attain insight into group behavior and class

morale and into the individual children and their situations.

lLouis P. Thorpe and others, Studying 'Social Relationships in the

Classroom: Sociometric Methods for the Teacher (Chicago: Science---Research Associates, Inc., 1959);:P.~.

31

Since the sociometric test

cont~ined

criteria that were real

~nd

of

immediate importance to the children, the teacher should start here by

out the original agreement.

car~ing

She should group the class according

to the way the children made their choices.

Her object should be to pro-

vide for each student the best possible placement from his point of view

so

th~t

he can learn--both in human relations and for academic purposes.

When arranging sociometric groups, try to fulfill as many choices as

possible.

If the children have been allowed five choices, try to satisf.y

at least two of them.

The following are some good directions for forming

sociometric groups:

1.

2.

3.

h.

5.

6.

1.

8.

Decide on the size of the groups. Five is usually the most

effective for small group discussion.

Start with the unchosen pupils--place them with their

highest choices. Give them their first two choices if

possible, but do not place two isolates in the same group

unless it is necessary. Never place more than two isolates

in a group.

Consider those who received only one choice next. If the

choice ,a'-neglectee :r;-eoeived was reciprocated by him, place

the neglectee with the person with whom he has the mutual

choice regardless of the level of the choice. Then attempt

to satisfY his first choice or the highest level of choice

it is possible to satisfY without disrupting the groups that

have already been formed.

Continue to work from the pupils receiving the smallest

number of choices to the pupils receiving the largest

number of choices.

If there are conflicts in choices--several people having

chosen the same person--satisfY the choice of the child

who is in a weaker position in the group.

Do not put unchosen children near those who have rejected

them, into a closed cluster, or with a mutUEl pair.

Do not break up completely the existing associations, not

even those that may not be entirely desirable such as

closed groups.2

Check pupil arrangement to be sure eve~ pupil has at least

one of his choices fulfilled. 3

IGronlund, SOCiometry in ~ Classroom, p. 238.

2.raba and others, Diagnosing HtmWn Relations Needs, p. 238.

3Intergroup Education in Cooperating Schools,

Guide, p. hI.

!

Sociometric Work

32

It has already been said that we need to be aware of and value or use

group qynamics in the classroom because we then create a better learning

situation both academically and socially.

There are many different ways

that the teacher can use the sociometr1c data.

to organize effective groups.

Sociograms help the teacher

"Clioue patterns may indicate a need to

fom new groups for different kinds of activity to permit new friendships

to develop."l

"Through careful selection of the membership in a group

and proVision for a series of activities, it becomes possible for these

pupils to interact in desirable directions. n2

The teacher can use the results to fom committees and work groups

and to reseat the children.

Teachers are alerted to values or skills

needed in social relations.

Sociometric results can show the effect of

certain teaching techniques and learning experiences on social structure

in otherwise comparable groups of children. 3 The sociogram and its

results can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of school practices or

to see how well a new pupil is integrated into the class. 4

It also helps

with disciplinary problems by providing clues to the attitudes and values

underlying the difficulty.5 The results can help determine the placement

of exceptional children in the Gchool program.

Some studies have shown

that mentally handicapped children are not socially accepted in the

regular classroom. 6 The results of the sociogram help to identify

lxto gers, Men~a! Hygiene in Elementary Education, p. 296.

2Caldwell; Creatin~ Better Social Climate in

Sociometric Technioues, p. 38.

~

Classroom Through

lraba and others, Diagnosing Human Relations Needs, p. 96.

4Gronltmd, Sociometry in the Classroom, p. 17.

5~.,

p. 18.

6Ibid., p. 17.

33

leadership potential so that this potential can be developed.

The results

are also useful in studying special needs of children who are having

difficulty in adjusting to the regular school program.

the results of sociograms is in parent counseling.

I

Another use of

Parents can be told

in which areas the child has the best ?cceptance and where he needs help.

Parents may also add to the sociometric data by telling the teacher about

the child's play activity outside the school. 2 By discussing and analyzing

with the class any problems of relationships that arise in the class, the

children will come to understand the behavior of others.

As the children

work in groups, "they are able to appreciate different abilities as they

are encouraged to work and plan together.

supportive toward one another.

Children feel warmer and more

Fundrunental needs for recognition, affec-

tion, and a sense of belonging are met in group life. ,,3 Through group

work, the atmosphere of the class is improved and pupils get to know and

understand each other better.

The atmosphere is more conducive for good

mental health.

After grouping the childreniil some way or another sociometrically,

the teacher should not expect to see all the problems in the classroom

solved.

This does not happen overnight.

"It is the adjustment that

gradually t?kes place in an enduring way which are so satisfying.,,4

"Teachers usually report that they notice an immediate change in pupils1

IGronl1md, Sociometry in ~ Classroom, p. 326.

2Barr , The ElementaEY Teacher and Guidance, p. 155.

3Los Angeles County-Superintendent of Schools ,Office, Guiding Today's

Children (Los Angeles: California Test Bureau, 1959), p. 54.

4Intergroup Education in Cooperating Schools,

Guide, p. 241.

!

Sociometric Work

34

attitudes when the sociometric choices are put into effect.

The isolated

pupils tend to feel accepted since they are placed with some of their

choices.

They have no way of knowing

are told by the other children.

th~t

they were unchosen unless they

The members of minority groups tend to

feel less tension since they are placed with majority group members and

the cleavage they feared did not appear in the sociometric grouping.

These feelings tend to be reflected in improved morale and more active

participation in classroom activities.

Thus, the groundwork is laid for

improving social relations. Hl

The children benefit greatly in their personal lives as a result of

group work.

"When the boys and girls can be associated closely with those

who respond to them and to whom, in return, they feel attracted, they

have a greater sense of inner security.

their inhibitions and act naturally.

Then they feel that they can shed

They feel free to be themselves and

to react positively without inner dread of possible disapproval. H2

"MOre

creative work should come about and fewer tensions within the classroom

should be noticed.

The flow of communication should improve, and natural

discipline should develop from children wanting to please others in the

group.H3

Using the sociometric results in group work begins

HAs the social climate of the class improves, so will the

a circle.

soci~l

adjustment

of the individual students, particularly those who have been isolated

because of group attitudes toward them.

And in turn, as each child grows

in social effectiveness, class social integration grows, too.Hh.

lOronlund, SOCiometry in the Classroom, p. 241.

2Caldwell, Creating Better Social Climate in the Classroom Through

Sociometric Techniques, p. 40.

3Melba A. Htming, "How Well Do You Know Your Class,ft ~ Teacher,

LXXIX (March, 1962), p. 107.

hrhorpe and others, Stugying Social Relationships in the Classroom:

Sociometric Methods for the Teacher, p. 37.

35

Sociometric results h:lve many uses.

By a sking certain

questions, the test can be used for different purposes.

should carry out the original agreement.

strongly.

particul~r

The teacher

This point is stressed very

If the teacher carries out the original agreement, the children

know they can trust and believe her.

Putting sociometric results to use in grouping the children in different ways gives the children an opportunity to know other children in

the

cl~ss.

Some children are too shy or do not have enough time in school

to become acquainted tmless they sit next to them, phy with them, or walk

wi th them to and from school.

The dynamic s wi thin the group should be

such that children learn to know and understand each other better.

They

also learn to appreciate and know others who are different in some way-another race, religion, or personality type--from them.

This is very good

because children need to know and appreciate people who are different from

them whether they live in the same neighborhood or in another part of the

world.

IX.

Isolates--Stars.

Working with isolates and stars is part of putting the sociometric

results to use.

It is up to the teacher to try to help these pupils ful-

fill their needs.

Although the star has received many choices and the

isolate none, this does not necessarily mean that the star is liked by

everyone. and is well adjusted or that the isolate is disliked by everyone.

No child in the

cl~ss

will be accepted by everyone, and few will be com-

pletely unaccepted by everyone.

The isolate is someone that the teacher needs to help because he has

several problems to work out.

The isolate may be the seldom confOrming

child that attracts everyone I s attention.

Usually this person cannot work

36

with a group.

The isolate may also be the overlooked child who is con-

forming and silent. 1 ·Some teachers feel that if a child is not accepted

by his peers in the early grades, he

,~ll

interpersonal reI a tions as he grOtIS up.

which indicates

th~t

not be able to develop normal

There is a good deRl of research

the child who is not accepted achieves at a lower

level than other members of his elementary-school class. H2 Since personality patterns are often formed. according to psychologists, by the

time the child is six years old, it is possible that the child will not

become accepted by his peers i f he is not accepted by them in the early

grades.

"Eve~

individual grows into a person whose

by me.ting the demands of his environment.")

begins.

The

enviro~~ent

beh~vior

is shaped

A vicious circle often

shapes the personality.

If this

personal~ty

is

not accepted by the pecor group because of certain ch3.racteristics or

behaVior, then the pesr group isolates the person.

§,ggravates the undesirable traits.

This in turn only

The person ...ho acts aggressively in

order to get ?ttention and is then rejected by his peers, only tries

harder to get attention and is only r3jected further.

Isolated children often

e)~ibit

certain

co~~on

characteristics.

Unpopular children are less self-confident, less cheerful, less enthusiastic, less acceptant of group standards, less conventional. and less

concerned with social approval than popular children. 4 Least popular

1Los Angeles County Superintendent of Schools Office, Guiding

Today's Children, p. 61.

2Edmund Amidon, "The Isolate in Children's Groups," Journal of

Teacher Education, XII (December, 1961), p. 412.

)Jones, The Use of Sociometric Data and Observational Records as

Guides for PromotIng SOcial and Intd'iI'eCtual Growth of Primary Children, p. 2.

4Guinouard and ~chlak, "Personality Correlates of Sociometric

Popularity in E1ementa~ School Children," p. 442.

37

children show less Qbility or desire to control their emotions.

more self-centered. jmpulsive. and moody.

They are

Often they are unable to react

to a situation although they often have the desire to participate.

1

Sometimes a child is isolated. not because of his personality. but because

of certain factors ?resent in the classroom culture.

Also. i f a teacher

dislikes a child and communicates this c:islike to t:le class, this may

cause the children to isolate this child.

2

Each isolate should be treated as a separate case; the tool used

should be fitted to the particular situation.

used. the teacher ought to have

using the techniques, some

3.

"Before techniques are

clear understanding about why she is

~"ell-thought-out

hypotheses about how the

techniques will affect the group, ani a formal or informal procedure

which can be used for evaluating the SUCGess of the technique.")

The

teacher should take into consideration the pupil's social aspirations.

the pattern of factors causing the pupil's social difficulty. the pupil's

skills. abilities, and interests. the values held by group members, the

degree of emotional disturbance underlying the pupil's social behavior.

4

and thE pupil's social potential.

The teacher can do many things in the classroom to help the isolated

pupil.

She can encourage the child to take responsibilities that his

classmates 1fill recognize and 3.)preciate.

She can hel? him with his

personal apf)earance and to practice and develop skills and abilities which

1 NorthHay, ',fua t Is Popularity?, p. 12.

2Amidon. "The Isolate in Children's Groups." p. 412

)Ibid •• p. 416

4Gronlund. SOCiometry 1:ll ~ Clas':.;room, p. 297.

38

have prestige

i~th

his classmates.

The teacher can help the child under-

stand how his o'tm behavior affects the feelings of others.

If the child

has interests and hobbies. the teacher can help him vTi th these.

The

child can then share them tiith the class andpperhaps achieve some social

success and recognition. 1

If the teacher maintains an accepting attitude of

~ersonal

warmth

and acceptance, this adds to the child's feeling of security and belonging.

Group techniques such as group discussions and role playing will

also help the pupil see his own behavior and

acceptable behavior.

\\~ll

help him find more

The teacher can also help to modify the values of

the group through helping the children to increase their acceptances of

differences in themselves and others.

· , · · dua1 conf erences

through J.nO-J.vJ.

Changes can also be brought about

. th pUpl'1 s. 2

\oil. •

lI~fuen

the pupil does not

respond to the teach8r's remedial efforts. he should be referred to a

professional counselor for special help.")

Although it is easy to forget about the star because he must be

popular and

~-Jell-adjusted

since he

i'laS

chosen so often, the teacher should

not neglect the star.

The star or popular Jerson may have adjustment

problems of his own.

People today tend to regard popularity as an end

in itself.

The va.lue of a person is judged by the nu.'Tlber of friends he

has, how many people know him, and hOI<1 m:my organizations he belongs to.

However, it is .oossible .that even though he

knO:JS

a lot of people and has

a lot of friends, he might not have one real friend.

He may kn01'l a lot

1Los Angeles County Superintendent of Schools Oftice, Guiding

Taday's Children, p. 62.

2Gronlund , SociometEY in the Classroom, pp. 280-285.

J Ibid., p. 297.

39

of people but be close to no one.

Northway asks the question of "is it

possible that we've overvalued popularity as an end in itself, and that

our emphasis of business and social success has made us lose sight of

some of the other values or human living?" 1

By

using a sociogram, it is possible to learn something about the

child's popularity and ,vh2- t i t consists of:

~.;hether

he has reciprocal

choices or is often chosen by people he does not choose; whether he likes

and is liked by both boys and girls; and whether belonging to a minority

group affects his popularity.2

popular.

It is hard to define what makes a person

Popularity appears to depend on the extent to which one's

energies are directed towards the goals the group values.

nSome children

work towards these goals easily, with genuine interest in and concern for

people.

Others do so with considerable effort and anxiety, not primarily

for the welfare of others. but to bolster their o".,rn insecurity and enhance

their o..m. egos."3

his environment.

light.

The very popular child shm{s a greater sensitivity to

He tends to

vie~·:

the situation in a conventional

Popular children do not shovT much originality in their thinking

nor do they seem to get a new slant on things.

They show a strong need

for affection and a conscious striving for approval. 4

Usually teachers consider the popular children to be the leaders of

the class.

"If we define a leader as a person with the ability to

influence others. we

1

Northway,

~

2Ibid • , p. 8.

3-..!2.L.

r °d I p. 17.

4Ibid •• p. 11.

c~n

see by looking at sociometric test results that

Is Ponularit;E? , p. 2.

almost everJ child is a leader to the extent that he influences those

\

who choose him.

'

','Ie can see. too. that most children also ?lay the part

of follmler; they choose and are influenced by others.

In fact, most

children are a mixture of lec.c.er and follo-;.;er, but some haves. stronger

tendency in one direction than in the other. n1

are at least

1.

2.

3.

~hree

different kinds of

Northway says that there

le~ders:

The popular leader--his influence is Ivide but not deep. He

forms no close associations with the people who choose him.

He gets others to follmT on impulsive ideas.

The po~{erful leader--he is not particularly powerful. He

has an average sociometric score. This score is made up

of popular children he has chosen in turn. Since he is

able to influence all of them. he holds the balance of power

in the group.

The Dower behind the throne--has a 1mV' score but is behind