Les Femmes Nouvelles: The Liberating Image of French Women by

advertisement

Les Femmes Nouvelles: The Liberating Image of French Women

in Fin-de-Siecle Bicycle Advertisements

An Honors 499 Thesis

by

Kristie Couser

Thesis Advisor

Dr. Ronald Rarick

Ball State University

Muncie, Indiana

May 2008

Graduation Date: May 2008

Les Femmes Nouvelles: The Liberating Image of French Women

in Fin-de-Siecle Bicycle Advertisements

An Honors 499 Thesis

by

Kristie Couser

Thesis Advisor

Dr. Ronald Rarick

Ball State University

Muncie, Indiana

May 2008

Graduation Date: May 2008

Abstract

.eli f;

During the fin-de-siecle, a period of political stability, rapid industrialization, and

economic prosperity in France, a burgeoning middle class emerged in Paris. In the lively capital,

Parisians enjoyed countless leisure activities, as the cultural center of Europe attracted a diverse

population of artistic, literary, and philosophical minds from around the world. Traditional

definitions of gender roles, however, limited the public activity of women to the domestic duty

of shopping for their families. Large, colorful lithographic advertisements produced by artists

were displayed amid the city streets, popularizing new consumer goods while simultaneously

helping to elevate the medium of lithography to high art status. The safety bicycle was one of the

most popular, and widely advertised, consumer products of the 1890s. In this paper, 1 examine

the representation of women in five bicycle advertisements, as men were rarely depicted in them

regardless of the bicycle frame often being a men's model. 1 heavily explore the social and

political environment of France as 1 discuss the context and interpret the intended message of the

advertisements, concluding that such images complemented feminist identities in French women,

speaking to their interests of literally moving beyond the domestic realm.

Acknowledgements

-I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Ronald Rarick, for his spirited response when 1 proposed

my thesis topic to him last fall. His enthusiasm for and commitment to my project throughout the

semester has resulted in a work of which 1 am very proud. His art historical expertise,

outstanding skill as an educator, and encouragement every semester has greatly enriched my

undergraduate experience.

-I would also like to thank Dr. Ted Wolner for being the most challenging and fascinating

professor with whom 1 have had a class here at Ball State. 1 thought 1 knew well enough how to

read, write, and critically think before 1 entered his Humanities sequence; 1 was wrong. 1 credit

the personal and intellectual growth 1 experienced in his courses as the main reason why 1

continued to pursue the Honors diploma.

The civil disaster of the Paris Commune marked the start of the Third Republic, a new

government that, according to its first president Adolphe Thiers, was the "regime that divided

least" after the humiliating defeat the French suffered in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71)

(Moynahan 32). Finally, after a tumultuous century of great political instability and international

and civil conflict, the French experienced a refreshing sense of national security, enjoyed

increasing economic prosperity and a burgeoning middle class, and dabbled in social reform

under the progressive Third Republic at the fin-de-siecle (Schardt 7). This confident, expansive

spirit was most apparent in Paris, a city focused on innovation (Collins 41).

In the mid-19 th century, despite continuing political strife, Paris underwent significant

change. Under Napoleon III, the urban planner Baron Haussmann transformed the narrow

medieval streets into wider, grand boulevards that beckoned the social elite and commercial

enterprises to make appearances (Tiersten 16). Rail systems were soon introduced, affordably

transferring the lower classes from the countryside to work in the city, while simultaneously

showcasing the growing city as a competitive economic force. Paris was also the site of several

extravagant Expositions Universelles, which proved to the world that France was on the mend,

demonstrating ceaseless industrial pursuit of technological innovation and confirming the status

of Paris as the vivacious, cultural center of Europe (Moynahan 33).

A common leisure activity in this era was strolling down the grand promenades,

particularly in the evening, and enjoying the countless activities found in the city-bustling

cafes, lively cabarets, and packed dance halls. Famous entertainments, such as the Folies

Bergere and Moulin Rouge, were immortalized through the large, energetic chromolithographic

2

posters made by artists such as Jules Cheret (1836-1932) and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (18641901). These images of Parisian leisure merged avant-garde artistic ideas and transformed the

streets themselves into a "picture gallery" (Gretton 115). Paris drew talented and curious people

from around the world, and unless they staunchly objected to the decadent lifestyles made

famous by the city, they could find community among the multiplicity of artistic, literary, and

philosophical minds that flourished there (Moynahan 45).

However, the many pursuits of the city were mainly reserved for young, privileged men

and the women they accompanied. Though society was more progressive than under earlier,

chiefly aristocratic or monarchical rule, the ideals ofthe Third Republic continued to emphasize

the differences between the sexes. The majority of people held onto the concept of "separate

spheres" for men and women, which sought primarily to keep women in domestic environs

(Silverman 73). The advent of the department store brought about the most "accessible social

arena" for women in public life and legitimized the public appearance of women because it

allowed them to fulfill their domestic duty of shopping for the home, a task inextricably tied to

nurturing the Republican family (Gretton 113; Tiersten 23).

Though thefin-de-siecle tendency of consumerism itself gave women public visibility,

one ofthe products being sold allowed them, as well as people of all ages and classes, the ability

to take to the streets as never before. By the late 1880s, the mid-century invention known as the

velocipede had been refined into the more comfortable, affordable safety bicycle (Herlihy 278).

From its debut, people were drawn to the bicycle as a curious machine, an exciting means for

3

transport, exercise, and leisure. By 1900, there was one bicycle for every 32 people in France

(Foley 159).

The bicycle had great impact on French society as a technical innovation, but for women,

the bicycle was one of the most transformative inventions of the century because it gave them

unprecedented mobility and thereby a sense ofliberation from male supervision. The nature of

the bicycle itself excited debate over women's health, sexuality, public appearance, and changing

familial and societal roles. Despite the controversy, women continued to ride. To the social

conservatives of the era, as well as women eager for liberation, the bicycle was closely tied to the

femme nouvelle, a "new woman" who had social and economic aspirations beyond the foyer

(Foley 157).

In this essay, the social and commercial environment ofthe 1890s will be considered

with particular interest in the controversial, though liberating, effect of the safety bicycle on the

lives of French women. A selection of bicycle advertisements featuring female figures will be

examined, noting the representation of women and connections to the advance of the femme

nouvelle. As a commercial product of great interest to both sexes, advertisements of the bicycle

were intended for a wide audience, though it can be seen that even images intended for men

communicated ideas of liberation to women. In addition, the array of artistic styles of Paris at

the end ofthe century will be discussed as a necessity because chromo lithographic prints were

considered an integral part of popular culture and were often collected by the pUblic.

4

Ushering in the "Golden Age"

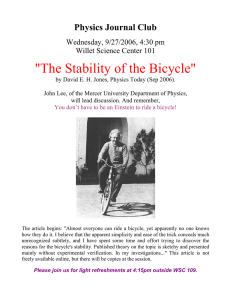

In the chromolithographic poster {'Etendard Frant;ais (1891) [Fig. 1], the revered French

poster artist Jules Cheret (1836-1932) promotes the bicycles and tricycles available at the

Ateliers de Constructions Mecaniques of Paris by featuring his archetypalfemme de Paris

elegantly seated upon a bicycle. Wearing a stylish blue, white, and red wasp-waisted dress, she

is herself the tri-color as she carries a flag, exuding confidence with good posture and a slightly

lifted chin. Cheret is selling the "French Standard" bicycle in his characteristic, wildly

successful way; the bicycle appears to be an afterthought when compared to the strong presence

of a vivacious, colorfully rendered woman upon it.

By the 1890s, Cheret had been a well-known and prolific poster artist for nearly 30 years,

applying his mastery of the lithographic medium and innovative spirit to designing large scale,

eye-catching advertisements for the diverse, emerging industries of Paris (Abdy 9). Cheret

illustrated a wide variety of products, from medicinal throat lozenges to alcoholic beverages,

being used by stylish, buoyant people who dominated a brightly colored, painterly field (Schardt

20). His skill lay not only of creating an alluring vision offin-de-siecle life, but also in knowing

how to capture and hold the gaze ofjlfineurs, the public that strolled through the city for leisure,

through simplified imagery and dazzling handling of color (Gretton 115). Through his career in

designing over 1,200 images, Cheret was not only responsible for "rediscovering" the function

and potential of the lithographic medium, but fully realizing it in terms of commercial use and as

a legitimate art form (Schardt 19).

5

After Cheret's celebrated application of "high" art to industrial and commercial printing,

countless designers followed suit and became commercial artists as a way to earn a living (Abdy

9). The tumultuous century had culminated with a tendency to fusion; antiquity, Rococo,

Japanese woodblock prints, and medieval illuminations were all sources of illustrative style.

Cross-cultural influences and art historical references are evident in the work of two of the most

successful poster designers working in Paris, Alphons Mucha (1860-1939) and Henri ToulouseLautrec (1864-1901). The popularity of such artists and their print work, along with Cheret, was

responsible for confirming the 1890s as a "golden era" of illustration (Arwas 7).

Because of the designers' deft abilities in making an eye-catching and breathtaking

image, the public fell in love not only with the new consumer goods depicted in a poster, but

often the poster as an object. It was not uncommon for freshly pasted posters to be removed by

the passers-by who desired to decorate their homes with the work. There was also a surge in

popularity of fine art prints amongst the public, as amateurs avidly collected affordable etchings

and lithographs (Abdy 21). According to Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), the poster work of

Cheret and his contemporaries was a "welcomed change" as it rejected the tired, "pompous"

academic art of the prior era (Abdy 22). For the first time, an "intimate relationship" existed

between art and life for the average person (Schardt 16).

The Emergence of the Fliineuses

The jlaneurs of the urban environs played an essential role in popularizing the poster art

of the era-but who exactly were these dawdling pleasure-seekers and what was their

relationship to the ever-present commercial poster image?

6

In the second half of the 19th century, Paris provided its growing popUlation with

numerous leisure activities: athletic pursuits in public parks, such as the popular Bois de

Bologne, shopping one's way up and down the newly-revamped, "opulent" boulevards in the

heart of the city, or indulging in the seamier side oflife through attending one of the nightly

revues or dance halls (Silverman 16). For middle and upper class men, the streets of Paris were

avenues of endless entertainments along which they could amuse themselves for hours while

running errands; strolling soon became an activity itself (Gretton 114). Until the near end ofthe

century, however, most ofthese outdoor or public activities were not socially acceptable or

permitted for an unaccompanied woman or even a small group of women. Women were seen

chiefly as responsible for maintaining the foyer and carefully raising children to be instilled with

Republican values (Foley 131). In other words, the prevailing attitude of the Third Republic at

its inception was that a woman was limited to the "private sphere," best complementing her

husband and strengthening her country by assuming domestic roles that accentuated her

femininity.

The social and political system that essentially barred unaccompanied women from

public leisure activity also sought, as a means to retain sexual polarity, to keep them out of state

institutions, such as education (Tiers ten 23). Before the 1880s, secondary schooling did not exist

for all women; only the privileged were able to receive education beyond the state-sponsored

primary school system that had been established thirty years prior (Foley l30). Even then, a

woman's "higher" education was often limited to preparatory courses on how to maintain a

proper household and marriage, as well as child rearing (Silverman 66). By the tum ofthe

7

century, the new access women had to secondary education began to bring them steadily into the

work place, beyond the factory. The majority, however, remained limited to the private,

domestic "sphere" which was separate from that of the rational, well-defined male (Foley 136).

The attitude of men and women being of separate spheres was not only based on longstanding social conventions, but also was most pertinently advocated by the scientific

community, which saw its research as a confirmation. Increasingly, anthropometric studies and

medical studies of the human body's processes served as confirmation of male superiority via

Darwinist theory (Foley 135). One example ofthe interest in translating biological sexual

differences into the social realm was the view that gender was considered embedded in nature, as

ovaries were understood to be "passive" compared to the "active" male sperm (Foley 135). The

leaders of the Republic felt that observing the greater implications of such biological differences

was necessary to keeping social order (Silverman 73). This was taken literally to the extent that

any threats to sexual polarity, such as the femme nouvelle and the liberating nature of the bicycle,

were perceived to lead to "impotence, sterility, and race suicide" by political leaders ofthe era

(Foley 135).

Women had more freedoms in Paris than in the country, partially due to the presence of

factories and their growing female workforce. It was the city's commercial growth and large,

luxurious department stores, however, that brought about the presence of unaccompanied women

in the male dominated public sphere. Grand department stores appeared in the 1860s, shortly

after Baron Haussmann transformed the narrow city streets into magnificent boulevards (Tiersten

22). Men, and the woman they accompanied, had been casually promenading on the boulevards

8

as a social activity, but the department store quickly became solely the woman's promenade, as

consumerism was associated with the interests of women or essentially female responsibilities

(Gretton 114; Foley 156).

A woman's domain was the household, a private, interior space in which her family was

comforted by her moralistic behavior and attentiveness. She was responsible not only for

keeping the space clean and orderly, but also for embellishing it with goods and decor that

reflected her careful, "natural" aesthetic sensibilities (Tiersten 23). As mass production made

available an array of cheap consumer goods, the middle and upper classes were increasingly

driven towards ownership. Since a woman maintained the home, the purchase of commodities

became, by the end of the 19th century, a seamless extension of her domestic identity (Foley

157).

The spacious department store, which was quickly becoming a fixture of Paris'

commercial districts, initially attracted women because it catered to their domestic needs.

Offering a wide range of goods in one location, the department store provided unprecedented

convenience to the point of being called "a city within itself' (Gretton 114). The one-stop nature

ofthese stores encouraged the idea that women could shop alone because it minimized their

contact with the "brutishness ofthe streets" (Tiersten 23). In this sense, the department store

took into consideration the anxiety that men (and the Republic in general) felt about women

moving about the public sphere without supervision.

Inside this commercial setting, however, women were able to "circulate freely" in a

controlled, interior environment that welcomed their presence with stock that appealed to their

9

delicate tastes (Gretton 114). It quickly became common for groups of bourgeois women to

enter a department store as a social activity, with the intention of spending their entire day

actively shopping or looking around at wares (Tiersten 17). Advertisements portraying content

family life and other domestic activities covered the product displays, barraging the unrestrained

female shopper with the idea that consumption was her duty (Foley 157). While feminine

advertisements reaffirmed Republican values, images of women delighting in urban contexts,

appeared ever more. Such images emboldened a woman's decision to continue venturing into

the city, as they could see that their new identity was being recognized, however, these images

were still through a "less threatening," entirely commercial context (Gretton 117).

By the mid-1880s, unaccompanied women were more visible on the trains and along the

streets of Paris than ever before, largely because of the development of "commercial zones," or

shopping districts, surrounding popular stores (Tiersten 22). The growth of consumer culture

prompted women to explore a variety of competing commercial outlets on their way to the grand

department stores. The activity of shopping had become the most acceptable public activity for

women andjlanerie, or strolling for leisure, became a progressively common diversion for

women.

As middle class women were beginning to enjoy their afternoons as urbanjlaneuses, the

introduction of a physically and socially liberating product brought them back to the storefront.

When the velocipede was unveiled in the late l860s, only wealthy men and their wives had

access to the vehicle. By the early 1890s, the mass produced safety bicycle was first affordably

introduced to the middle and lower classes, quickly becoming one of the most popular consumer

10

goods ofthe era (Herlihy 278). Controversially, women took to the bicycle as never before,

challenging complex social conventions as they rode away from the home, into the city and

countryside, and out from under male supervision. For women, the bicycle was not only an

exciting mode of transportation, but was also a form of liberation.

The Democratic New Vehicle of the Republic

"This horse of wood and iron fills a void in modern life;

it responds not only to our needs but also our aspirations."

-Le Monde Illustre, Spring 1869 (Herlihy 127).

In his poster Cycles Clement (1898) [Fig. 2], Jean de Paleologue (1860-1942), known as

"Pal," delivers a message of French technological victory. A female figure dominates the image,

donning a gauzy dress and winged sandals (an attribute of Mercury), leaping forward as she

hovers above Paris along the Seine. Her left arm is extended forward, proudly displaying the

Clement safety bicycle in front of her body. Her right hand is raised triumphantly in the air as

she grasps a laurel wreath, symbolic of victory. Just below and to the right of the laurel wreath, a

stylized hat in the form of Ie coq de gaulois, a French cultural emblem, sits upon her head.

Confident in her posture as she springs towards the viewer, the woman is an allegory of French

progress, prideful in celebrating the refinement of the safety bicycle within the city of its

invention.

Pierre Michaux of Paris had finally realized the age-old dream of human powered

transport in the spring of 1867, after several Frenchmen struggled for decades with awkward,

cumbersome vehicles, such as the draisine, which were no more than wheeled "walking aides"

11

(Herlihy 75). Michaux's wHocipede, a chainless two-wheeler with pedals attached directly to the

front hub, found immediate success in Paris. However, the high cost of ownership limited its

early clientele to upper class men. Passionate about the potential ofthe new vehicle as a

common mode of transportation and exciting sport, these men often rode in groups down the city

streets to show offthe ease of use and speed ofthe bicycle (Herlihy 78). By the end of 1868, the

public was broadly aware of the velo and intrigued by the novel opportunities it offered; the

French fascination with the bicycle had officially begun.

Although costing over three months of salary to the middle class worker upon its

introduction, the velo was an alluring machine to people of all classes and of either gender, both

on practical and philosophical levels (Bouffard 9). For one, the velo did not require any special

skill to use, though one was wise to take advantage of the free riding lessons offered by many of

its manufacturers (Herlihy 81). Though initially expensive, in the long run it was cheaper than

maintaining a horse or continually paying for other transport. The velocipede was appreciated as

a fast mode of transportation to get to work that also came with the benefit of exercise. The

average cyclist was capable of traveling at eight miles per hour and could ride several miles

"with the exertion of walking one" (Herlihy 75). It enabled workers to search beyond

comfortable walking distances for better, higher paying jobs or different opportunities (Bouffard

11). Cycling was also enjoyed as a natural, relaxing experience that freed the worker from

"mechanical restraints" of their jobs and fixed train schedules (Garvey 70).

The price came down as more manufacturers produced the velo, but it was not in the

hands of the average person until near the end of the century. The most basic models could cost

12

as much as two weeks' salary for a teacher; the most personalized and luxurious bicycles could

cost up to three months' pay (Bouffard 9). The early pricing competition did, however, begin to

alleviate the only obstacle to ownership, as social status or gender themselves did not decide who

could ride.

Though only a small number of women took to the velo because of its cost, women were

greatly interested in the vehicle as a form of leisure, exercise, and independence. From the start,

they were aware that this revolutionary form or transportation could also help push for much

needed social reform (Herlihy 3). Society was quick to view and criticize early female cyclists

as scandalous, daring, and downright "outre," for participating in a masculine activity in the

public arena (Wosk 92). Sport activities had long fostered community among men, allowing

them to develop strength, confidence, and exercise in arenas offlimits to women (Foley 160).

Despite the debate over the aggressive nature of the sport of cycling, women's velo races were

organized shortly after the introduction of the vehicle. Though few in number compared to men's

races, they were popular events (Herlihy 100).

One notable race took place in Bordeaux in November 1868, drawing thousands of

curious spectators (Herlihy 135). Daringly, these women shortened their skirts, or even

controversially, wore pants, though mainly out of necessity; the velo was difficult for women to

ride without getting their long, draping skirts caught on the pedal, or even more dangerous, in the

spokes. Female and male spectators supported such races because the women were adept

cyclists, comparable to men. The riders were viewed as celebrities, championed for their

reputations as fierce competitors (Herlihy 136). Women were especially inspired by the show,

13

viewing the competitive, exciting races as signals of social progress (Wosk 92). Any foray into

the public sphere, whether shopping in the city or riding a bike, was embraced as an opportunity

for change from the monotonous, "cramped and contracted" life women had been unnaturally

living indoors (Wosk 99).

The majority of the public, particularly in the countryside where races took place, was not

ready for "real" women to ride just yet. Satirists often portrayed them as amazones who tore

through the streets on their velos, abandoning their husbands and children (Foley 160). The

images were of thick, masculine women with "obscenely" exposed legs. Another common

image of early women cyclists played off ofthe stereotype that women could not understand

machines and involved bumbling women in stylish dress awkwardly sitting upon their velos,

barely able to control the sophisticated vehicles (Wosk 95). Both examples exposed society's

anxiety about the unabashedly liberating nature of the bicycle, as it was fast, easy to use transport

that could carry a woman into the city, countryside, or wherever she chose to go, alone and

unsupervised (Garvey 69). Since women did not need the assistance or company of men in order

to ride a bicycle, female cyclists were perceived as challenging natural gender roles and

threatening the breakdown of social order (Foley 135).

Leaders of the Republic who clung to the idea of separate spheres that kept women in the

foyer, again used biological science to argue against women's use of the bicycle, stating that a

woman's "natural fragility and modesty" were reasons they should avoid riding (Foley 159).

Public controversy about women's issues, particularly sexuality, quickly developed. These major

social concerns, however, could not stop the mass production ofthe safety bicycle in the 1890s,

14

and were only heightened as the new bicycle was rigorously marketed to and purchased by eager

women.

The safety bicycle was an improved version of the velOcipede that had pedals attached to

a chain, enclosed gears, and a coaster brake (Wosk 97). In 1891, Edouard Michelin (1859-1940)

and his brother Andre (1853-1931), owners of a rubber factory, patented tires with removable

inner tubes (Bouffard 15). Formerly, the velo had solid, one-inch thick tires that were glued

directly to the rims. The safety bicycle used Michelin's pneumatic tires, soon produced by

several manufacturers, which provided a faster, more comfortable ride and reduced rolling

weight dramatically (Bouffard 16).

The greatest appeal for women, however, was the introduction of a drop frame

"feminine" model that debuted alongside the men's diamond frame safety bicycle (Garvey 69).

Instead of extending from the handle bars to just under the seat, the crossbar on the women's

frame swept down low near the pedals, allowing long skirts to drape slightly more comfortably

and retain the rider's modesty (Wosk 97). Bicycle manufacturers had witnessed the growing

trend of female cyclists in the years since the invention of the velOcipede, and though women had

been determined to own a bicycle regardless of a feminine option, the innovation confirmed in

women's minds that cycling was an appropriate leisure activity in which they felt welcome to

participate.

In 1893, a few years after the more accessible safety bicycle became popular, there were

over 130,000 of them in Paris; five years later there were one half million (Bouffard 9). The

extraordinary popUlarity of the bicycle was largely due to its new affordability, functionality, and

15

enthusiastic riders, but as a product that debuted during the "golden age" of illustration infin-desii!cfe Paris, one cannot discount the effect of its colorful advertisements.

The Safety Bicycle and les femmes de Paris

Like other competitive manufacturers of Paris' famous products, such as cosmetics,

clothing lines, fashionable accessories, and cigarettes, operators of bicycle shops established

their brand name and increased sales by plastering the streets with large chromolithographic

advertisements. All advertisements that were pasted along the city streets served a specific

purpose-to catch the gaze of the passers-by and sell them a new vision of themselves, bettered

by a product. Regardless of an artist's stylistic influences and individualized handling of color or

line, the human figure, typically female, was always predominant in the field of posters in this

period (Schardt 16).

In the case of the bicycle, a product that was purchased and used by both sexes, the

representation ofthe female figure was different from poster to poster. In general, there were two

tendencies. To capture the interest of women, especially aspiringfemmes nouvelles, fashionably

(and more rationally) dressed modern women were portrayed assertively cycling alone, often in

the city. The male gaze was caught with alluring, scantily clad female allegorical figures that

promoted the industrious, more "masculine" qualities ofthe bicycle. Both sexes, however, were

likely to find appealing aspects of the posters, as they celebrated one of the most wildly popular

consumer products of the period.

In Lucien Baylac's (1851-1913) Cycles de fa "Metropofe" (1893) [Fig. 3], afemme de

Paris expressing the same buoyant spirit as the cyclist in Cheret's f'Etendard Fran{:ais [Fig. 1] is

16

centered, riding a safety bicycle. She wears a stylish green dress with puffy shoulders and a long

skirt with ruffled hem, tied at the waist with a yellow sash that matches her stockings. Upon her

head is a large tan hat adorned with feathers and a few flowers. A few locks of her dark hair are

hanging loose, blown back as she pedals forward on her bicycle. The bicycle, a women's safety

model with pneumatic tires, is in motion, as described by Baylac's vague rendering of the spokes

and the skirt of her dress and sash fluttering behind her. She smiles radiantly, glancing off to the

side as if communicating with a person on the street. Her left ann is raised into the air with her

hand gesturing what is likely a friendly greeting to someone with whom she has made eye

contact. The backdrop is a painterly scene in pure red and blue, not indicating her environs,

though the shop being advertised is named "Metropolis Cycles," suggesting an urban locale.

Unlike the posters ofCheret [Fig. 1] and Pal [Fig. 2], Baylac's image intentionally

communicates to a female viewer. In Cheret's poster, hisfemme is dressed in contemporary

style but she is an allegory for the nation, a modem Marianne, with a tricolor dress, lapel pin,

hat, and pennant in hand. Pal's female is a purely allegorical figure, celebrating the French

achievement of the invention of the bicycle and progress of industry as she holds a men's frame

bicycle. Traditionally, female personifications of ideals, such as liberty and virtue, are found

throughout painting and sculpture. Women are handled in the same way through the lithographic

medium, though the purposes of these works are different in that they are commercial.

Representations of female archetypes and goddesses were common in the Industrial Age

as a way to impart "dignity, legitimacy, and stability" to the changing, mechanizing world that

was exploring new technologies and altering traditional lifestyles (Wosk 17). These allegories,

17

though female, are not specifically selling bicycles to women or making commentary on the

social status of women so much as they are following an artistic and philosophical tradition.

Women would have understood the emblems and enjoyed viewing the posters amid the streets,

but such advertisements did not have the same impact as images celebrating the "real," modem

woman.

In Cycles de ia "Metropoie" [Fig. 3] Baylac acquaints the viewer with a stylish woman

riding a drop-frame safety bicycle. She is riding alone and with confidence, making eye contact

and gesturing to someone as she rides. The bicycle being advertised is of the mhropoie and is

being used by a vibrantfemme de Paris, merging the interests of manufacturer with a liberating

image greatly appealing to fldneuses. Unlike Cheret's image, which was laden with Republican

symbolism, Baylac's woman is more closely a real-life femme de Paris, or at least glimpse of the

independent, public identity that French women were striving to develop at the tum of the

century.

Portraits of radiant, unaccompanied women in less restrictive clothing (like the model in

Baylac's poster [Fig. 3]) are commonly found in bicycle advertisements of the 18908. Though it

served the manufacturer's purpose of selling more products, bicycle advertisements tapped into

the contemporary debates about women's social identity, promoting the bicycle as a mode of

transport for the "new woman" (Gretton 119). The active, confident women depicted in these

posters became icons of freedom and mobility, reflecting the desire that women had to enter the

public sphere beyond the department store. Ideas of reshaping women's social identities in a

commercial context were much less threatening than efforts in the political arena, as debates for

18

and against maintaining traditional gender roles were particularly heated during the jin-de-siecle

(Gretton 116).

The new cultural image of active women pursuing public lives, however, was not just an

advertising phenomenon. Middle class women were coming to identify themselves as femmes

nouvelles, women with aspirations and expectations beyond the foyer, and were entering

educational institutions and professional careers as never before (Foley 157). Countless

representations of the femme nouvelle in journals and publications from the 1890s pair her with a

bicycle, which literally and figuratively liberated her from her traditional, interior lifestyle

(Silverman 63). Though a relatively small number of women fully assumed this new careeroriented identity prior to World War I, the signs of change were becoming quite visible with the

movement towards dress reform at the end of the century (Gretton 116).

The Controversial Call for Reform

"More violent than any revolution [the bicycle] has entered customs,

turned traditional opinions on their head, erased fearless resistances,

and put pressure on old police ordinances on costume."

--Georges Montorgueil (1857-1933), author (Gretton 119).

The first International Congress on Women's Rights was held at the 1889 Exposition

Universelle in Paris, marking the "coming of age" of the feminist movement in France

(Silverman 65). A small group of upper class women, mostly "society mothers," met to discuss

social goals that would elevate the status of women in France (Silverman 65). The Third

Republic still sought to consign women to traditional roles, emphasizing the importance ofthe

19

family and its values as a way to maintain social order. Republican leaders already had anxiety

because of the declining birth rate, and they felt threatened by the growing German population

throughout the decade following the disastrous Franco-Prussian War (Silverman 66). Jules

Simon (1814-1896), a former French statesmen and influential philosopher, summarized the

Republican view ofthe women's condition with the statement, "women, in body and character,

are planned as preparation for child bearing" (Silverman 73). As women began to rally together

for social reform, Republican leaders, doctors, and scholars sought rationales to defend

traditional perspectives of gender, often seeking medical and biological proof ofthe

"unsuitability" of women's participation in public activity (Foley 160; Silverman 70).

The women at this convention, however, understood that any threat to the Republican

ideal of family, such as a rejection of the woman's role of childrearing and comforting her

husband, would impede their cause (Foley 135). Their agenda focused on promoting egalitarian

models of Republican families and promoting the idea of women as "independent individuals,"

capable of having identities beyond, but not neglecting, their familial obligations (Foley 148).

Although the event was small, it was noted by the press and Republic officials as signaling the

rise of a generation of women who were opposed to traditional gender roles (Silverman 65).

Feminists in France took a subtle approach to reform, working within Republican mores and

focusing on "superficial" changes, such as rational dress; women did not see suffrage as a

priority, unlike women's liberation movements in other nations (Foley 148).

In Jean de PaIelogue's Femand Clement & Cie. (1894) [Fig. 4], a female model freehandedly and with bare feet, drives a men's frame safety bicycle across the backdrop of a large

20

yellow crescent moon and white shining stars. Her figure, loosely dressed in a windswept,

diaphanous gown that flutters all around, is effortlessly poised upon the seat as she is literally

"over the moon," in a state of bliss. Her breasts are only half covered by the sheer dress as she

leans backwards, tossing her head and hair to the side. With a cheerful smile on her face, she

rests her head back against her left arm, which is wildly thrown up into the air. Her right arm is

extended upwards, a red lantern hanging from a support in her right hand. The symbolism ofthe

lantern is not certain, though it may just serve as a prop to guide her as she rides.

Pal's poster is an advertisement for a men's bicycle model and its image of a partially

clothed, voluptuous female figure would immediately grab the attention of aflimeur. The

woman does not, however, appear to be an allegory; her sexual appeal alone is selling the

vehicle. Although the advertisement is oriented towards the male gaze, images of women

abandoning themselves to bicycle rides had great appeal to female cyclists, who enjoyed the

sensation ofliberation that cycling gave them. The model's state of euphoria, evident in her

carefree posture and exuberant expression, sells the idea that cycling provides a feeling of

satisfaction through being physically unrestrained. Through using a bicycle, she is

disencumbered as she metaphorically soars through the sky without limit, and as she is simply

draped in a light, flowing fabric.

Prior to the socially acceptable activity offlimerie and the invention of the bicycle,

women were not only physically confined by an existence in interior spaces, but were literally

restricted by rigid dress codes that upheld the notion of feminine modesty. Conventional attire of

the mid-19 th century included corsets, long dresses, overcoats, hats, and gloves extending up the

21

arm, past the elbow (Herlihy 138). "Exaggerated ornamentation," such as voluminous skirts,

bustles, and bows, was added to women's clothes as a way to play up femininity, but it

contributed to garment weight and became cumbersome (Foley 157). Tight corsetry, which

quickly became a symbol of feminine oppression rather than femininity, was used to emphasize

the hourglass figure "natural" to the female anatomy (Bouffard 8). Even as long skirts turned

into bloomers and the corset was abandoned, an emphasis on the distinctly feminine hourglass

figure remained (Foley 158).

Dress reform had been talked about in elite social circles for a generation, with the

wearing of baggy "Turkish" pants adopted by only some women of privilege beginning in the

1850s (Herlihy 267). With thousands of women of all classes taking to the bicycle, the issue of

women's costume was pushed like never before, making the decades long goal of more rational

dress within reach (Herlihy 267). Sitting square on the seat in order to pedal a bicycle was

nearly impossible without struggling with the bulky, long skirts of conventional dress. Tight

corsets made it difficult to lean forward and properly breathe while riding; the practice of

wearing them largely declined because they were impractical for female cyclists, not because of

the achievements of the progressing women's movement (Bouffard 26).

When faced with the question of wearing bloomers, which had already begun to appear in

more athletic environments such as women's cycling clubs, or shortening their skirts in order to

better (and more safely) ride, the average women at first favored donning a knee-length skirt

paired with stockings that covered her legs (Herlihy 270). By the mid 1890s, a period of high

production of the safety bicycle, however, scores of Parisian women rode their bicycles through

22

the city, congregating in urban parks, such as the Bois de Bologne, confidently sporting

bloomers (Herlihy 269). The bloomer, trouser-like though still retaining a feminine look,

became so popular that, by the end of the century, cycling while wearing a skirt was viewed as

"passe" (Bouffard 32). Although the adoption of bloomers proved more practical for cycling, it

sparked public debate as the garment physically ''blurred the distinction" between the sexes

(Herlihy 269). The femme nouvelle was now impossible to ignore; she controversially exhibited

her aspirations on her body in the public sphere (Foley 157).

The increasing population of professional women, or women who aspired to enrich their

lives through participation in public activity, asserted a more practical form of dress, both during

and outside of their leisure activity of cycling. The femme nouvelle had a simplified, shorter

hairstyle, reduced overall volume in her clothing through shorter skirts and bloomers made of

thinner, breathable fabrics, and had abandoned the great symbol of feminine oppression-the

corset (Bouffard 8; Foley 157). Highly visible within a female population that generally

continued to wear long dresses, her public presence aroused fears of the "loss of feminine

modesty" (Foley 161). The sight of her calves (though covered by stockings), suggested to

traditionalists a more "sexual and dangerous" independent woman was emerging (Silverman 67).

The physical appearance offemmes nouvelles was subject to endless satire, as virtually all

publications ofthe period commented on the amazones or hommesses, the "masculine" women

who inverted genders as they rode their bicycles (Silverman 63). A common satirical image of

the femme nouvelle involved a strapping, bloomer-clad woman riding a bicycle away from home,

leaving her husband standing at the door, abandoned (Silverman 67). It was the goals ofthe

23

femme nouvelle, with aspirations of fully integrating into public life, however, that posed the

greatest threat to the state's ideal of domestic women who raised children instilled with

Republican values (Foley 131). Critics ofthefemme nouvelle, such as conservative statesmen,

sought to control the "problem" by attempting to limit or discourage her use of the agent most

responsible for her transformation--the bicycle.

As the birth rate was in fact declining, it was feared that women were seeking too much

independence from the tradition as they entered educational institutions or the professional field

rather than having children (Silverman 67). These feminist actions, perceived as ''tampering

with the female identity," and thereby inverting sexual roles, were viewed as dangerous to

society (Silverman 70). The bicycle had undoubtedly contributed to a woman's sense of

liberation, but critics ofthefemme nouvelle, however, viewed that impact ofthe bicycle with

great anxiety and fear. They condemned the bicycle for encouraging "immodest" attire and

feared the long-term consequences of the presence of the ''third sex" of masculine women, on the

Republican family (Herlihy 267). Unsupervised as they rode wherever they pleased, female

cyclists were feared to be engaging in "improper liaisons," experiencing sexual pleasure with

strange men; such anxieties were "nightmare scenarios" printed as disparaging advertisements in

popular publications (Foley 162).

Even more unnerving in the mind's of critics was the "intense pleasure" that could result

from cycling, a sensation that some bicycle manufacturer's advertised as a way to catch the

attention of women seeking an enjoyable hobby (Foley 161). Images such as Pal's Fernand

Clement & Cie. [Fig. 4], clearly illustrate the euphoric feeling of cycling, with a sexual

24

connotation used simply as a marketing tool. Panic was generated from such implications,

however, as the act of pedaling was thought to produce pleasurable feelings and increase the

instance of nymphomania (Bouffard 10). If a woman was freely experiencing sexual satisfaction

without a man, it was felt that the entire foundation of traditional Republic society, based around

a woman's sexual purity, her marriage and dedication to childrearing, would become unstable

(Foley 162).

Critics also sought to condemn bicycle use through biological and medical evidence,

which had been the rationale of Republican arguments about gender roles for decades (Bouffard

11). The attempt was based on the idea that cycling was a risky activity that jeopardized the

female biological processes necessary for childbirth; to be barren in a Republic that championed

childrearing would be a disgrace (Herlihy 267). Scholars called on doctors to confirm their

presumptions of cycling causing decreased fertility rates, complications in pregnancy, hysteria,

and spinal problems (Bouffard 11; Foley 160). Though doctors of the period suggested that

women should not ride while menstruating or pregnant, and recommended a gynecological exam

prior to one's first ride, they could not rationally dissuade women from cycling (Foley 160). The

bicycle was an excellent form of overall body exercise, improving the health of an increasingly

sedentary urban popUlation; the moral anxieties of an older generation could no longer be

justified through the medical community (Foley 160; Herlihy 75).

25

Conclusion

"The Parisienne of today goes everywhere, does everything,

and is interested in all. Her life has changed completely."

--Excerpt from the feminist publication La Fronde, 1900 (Foley 163).

In Cycles Terrot 1901 [Fig. 5], Plouzeau features the Dijon bicycle manufacturer's new,

improVed chain system as a small illustration in the poster's bottom right-hand corner. The true

focal point, however, is a daring, unsupervised female cyclist riding emerging from a tunnel

ahead of a moving train. Silhouetted against the black tunnel, the woman is thoroughly afemme

nouvelle from head to toe. Wearing bloomers, leggings, mid-calf boots, and a chemise with a

scarf, she is rationally dressed for comfort in cycling, freed from the corset and long skirts that

complicated such activity while still maintaining a feminine figure with a belt cinched at her

waist. Her hair is short with a small cap upon her head, reflecting the more practical style

embraced by professional women. The woman's head is turned back at the train steaming

behind her. The male conductor can be seen leaning out of his car's window, shouting at her as

she rides in the path of the train. She responds to his anger with a sassy gesture, Ie bisquer, a

teasing flick of the fingers outward from under the chin, asserting herself as she confidently

continues to ride ahead of the train. Her right hand holds on to the center ofthe bicycle's

handlebars, guiding her as she pedals onward.

In the thirty years following the debut of the velocipede, French women emerged from

the foyer, first entering the public sphere through the entirely commercial context of department

store. Large, colorful chromolithographic advertisements courted their domestic taste, presenting

26

them with a fashionable image ofthemselves, surrounded by material goods and their comforted

families. With the mass production of the safety bicycle in the 1890s, which introduced a model

tailored to traditional feminine dress, women began to participate in public, social activities more

than ever. Their view ofthemselves, increasingly resembling that of the confident, modem

femmes de Paris of safety bicycle in advertisements, was one of physical and social liberation

The daring, playful female cyclist racing a train in the 1901 poster Cycles Terrot [Fig. 5] is an

confirms the arrival of les femmes nouvelles, who would continue to drive towards women's

liberation into the 20th century.

27

Works Cited

Abdy, Jane. The French Poster: Cheret to Cappiello. London: Studio Vista, 1969.

Arwas, Victor. Belle Epogue Posters and Graphics. New York: Rizzo1i International

Publications: 1978.

Bouffard, Konrad. The Bicycle in French Art and Society: 1890-1914. Diss. Indiana University,

1996.

Collins, Bradford R. "The Poster as Art: Jules Cheret and the Struggle for the Equality ofthe

Arts in Late Nineteenth-Century France." Design Issues. 2. Spring 1985: 41-50. JSTOR.

Ball State University Libraries, Muncie IN. 14 Mar. 2008 <http://www.jstor.org>.

Foley, Susan K. Women in France since 1789: The Meanings of Difference. New York: Palgrave

MacMillan, 2004.

Garvey, Ellen Gruber. "Reframing the Bicycle: Advertising Supported Magazines and Scorching

Women." American Quarterly. 47. Mar. 1995: 66-101. JSTOR. Ball State University

Libraries, Muncie, IN. 21 Jan. 2008 <http://www.jstor.org>.

Gretton, Tom. "The Flfmeuse in French Fin-de-siecle Posters: Advertising Images of Modern

Women in Paris." The Invisible FHlneuse?: Gender, Public Space, and Visual Culture in

Nineteenth-Century Paris. Ed. Aruna D'Souza and Tom McDonough. New York:

Manchester University Press, 2006. 113-124.

Herlihy, David. Bicycle: The History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Moynahan, Brian. The French Century. Paris: Flammarion, 2007.

Schardt, Hermann. Paris 1900: Masterworks of French Poster Art. New York: Putnam, 1970.

Silverman, Debora L. Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siecle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

28

Tiersten, Lisa. Marianne in the Market: Envisioning Consumer Society in Fin-de-Sh::cle France.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Wosk, Jule. Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the

Electronic Age. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

29

Illustration Sources

KJA Vintage Posters, Maps, and Prints. L'Etendard Francais. 22 March 2008

<http://www.rainfall.com/posters>. Path: Search, franc;:ais.

La Belle Epoque Vintage Posters Inc. Cycles de la "M6tropole". 20 April 2008

<http://www.la-belle-epoque.com/>. Path: Online Catalog; cycles.

Vintage ArteHouse. Cycles Clement. 20 April 2008 <http://vintage.artehouse.com>. Path:

Search; bicycles.

Vintage ArteHouse. Femand Clement & Cie. 20 April 2008 <htttp:llvintage.artehouse.com>.

Path: Search; bicycles.

Vintage Poster Market Online. Cycles Terrot. 20 April 2008 <http://www.vintage-postermarket.com>.

~t

liers

D E

tl~m~nl~ I

113,Oua,

PAR

~mill

50 F~ll

PAR MOIS

1

DERRIERE tH EA 10

- · .L.

CEO L D IT' .

; E n v o ' Fr a c o du Cata log ue

Figure 1: Jules Cheret l'Etendard Fran9ais 1891

Source: KJA Vintage Posters, Maps, and Prints

Figure 2: Jean de Paleologue Cycles Clement 1898

Source: Vintage ArteHouse Online

Figure 3: Lucien Baylac Cycles de fa "Metropofe" 1893

Source: La Belle Epogue Vintage Posters Inc.

Figure 4: Jean de Pah~ologue Fernand Clement & Cie. 1894

Vintage ArteHouse Online

Figure 5: Plouzeau Cycles Terral 1901

Vintage Poster Market Online