CREATING LEAN SUPPLIERS: DIFFUSING LEAN

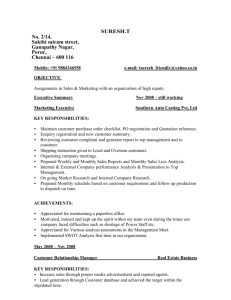

advertisement