J.

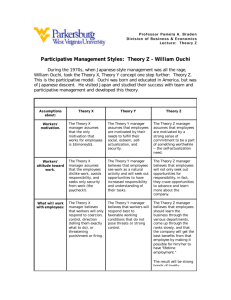

advertisement