THE DELAWARE COUNTY HOMEI Thesis Presented to

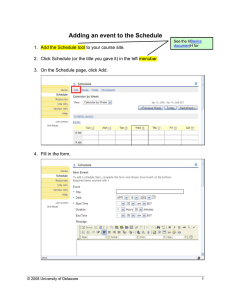

advertisement