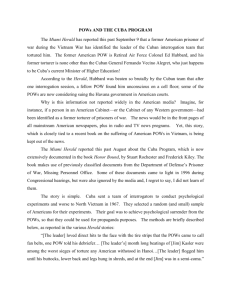

“ANY ONE OF THE PRISONERS WOULD HAVE BEEN WILLING

advertisement