ALL AT ONCE: Integrating Sustainability into Arts-Focused

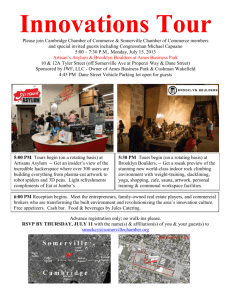

advertisement