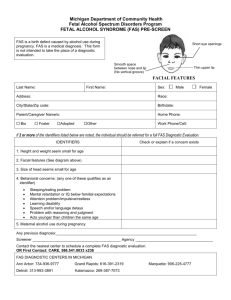

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: by Elizabeth Ackerman

advertisement