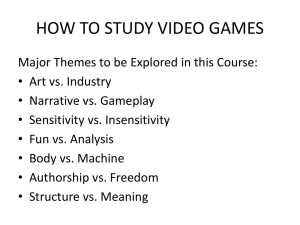

Poetics of the Videogame Setpiece Sonny Sidhu ARC

advertisement