Document 11186837

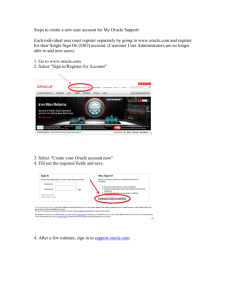

advertisement