Interface learning – New goals for museum and upper secondary school collaboration

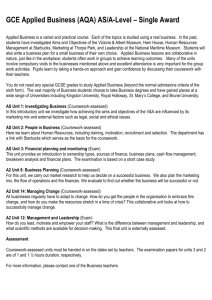

advertisement