A Roadmap to Resilience: Towards A Healthier Environment, Society

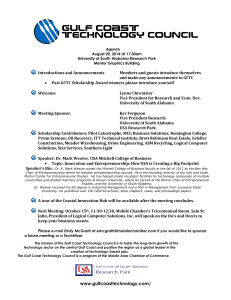

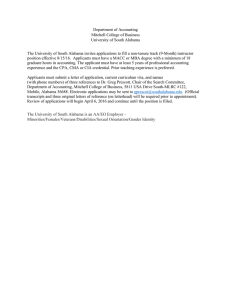

advertisement