ARCHNfVE Professionalization and Market Closure: The ...

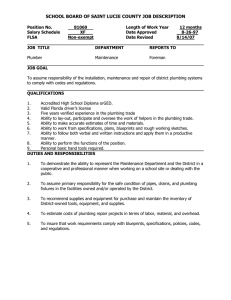

advertisement