CHERRY Discussion Paper Series The Opportunity of a Disaster: CHERRY DP 03/06

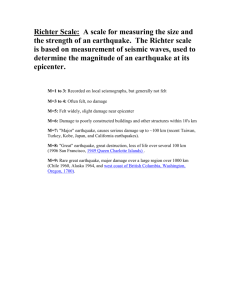

advertisement