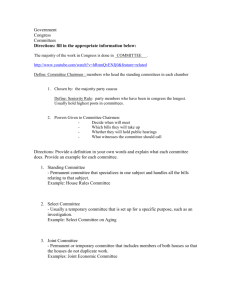

Order from Chaos:

advertisement