The Potential Economic Development Opportunities of Tren Urbano

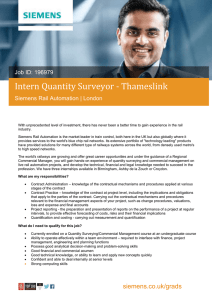

advertisement