The MetLife Study of Financial Wellness Across the Globe:

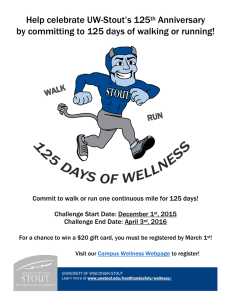

advertisement