A homily for 33 Fr. Joseph T. Nolan

advertisement

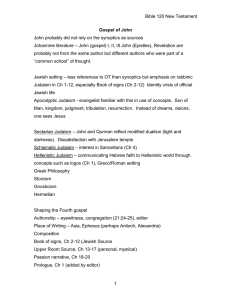

A homily for 33rd Sunday (C), Nov. 14, 2010. St Ignatius Church Fr. Joseph T. Nolan The gospel really does need sorting out. The first part is Jesus speaking, predicting the destruction of the temple, which did happen in 70 AD when it was destroyed by the Romans. But the latter part of the gospel is written in the style called apocalyptic, used by the authors to describe times of great upset. It may have been prompted by the frightful persecution of Christians ordered by the emperor Nero in Rome, a few years before the gospel was written. The message emerges that no matter what happens, no matter the convulsions of history, God is greater than all the forces of darkness and evil, even though they seem to win the victory for a time. The final promise of the apocalyptic text is that you will not be harmed, you will save your lives. This makes little sense in a world where the innocents are harmed every day and their lives destroyed by evil people. So, where are we? Still living in a dangerous world, and faced with our mortality every day. The danger we know well, especially since the mass death of 9/ll. Before that, and still, we have lived with the threat of nuclear war. The gospel describes a world of cataclysm and turmoil. Does history record anything else? Look at the pictures or visit some of the great wonders of the ancient world, the great civilizations, and it is easy to reflect upon the uneven course of history. The Roman empire lasted a thousand years and you can still see its mighty stones, most of all in the Coliseum – but it is a ruin, even though it is still used for great outdoor events. Visit Greece and you can see the Acropolis, impressive, but still marked by the shelling of Turkish guns in World War I. The 20th century gave us an unparalleled story of genius and evil. It gave us the airplane, and we turned them into bombers. It gave us a giant like Albert Einstein, and his discoveries led on the one hand to inventions like television, and on the other, the atomic bomb. The automobile went from the Model T – any color you wanted as long as it was black – to become everyman’s vehicle and accept 40, 000 casualties a year and a way of life that depends on oil. We learned how to live longer; we produced far more goods and creature comforts, and then discovered that we have been destroying the atmosphere and mortgaging our future. And all this time we have lived with the threat of nuclear war. Here is the account of a young man describing the first day of his life in l966. He writes that his father was an air force pilot, and “he carried a two-way radio in case war started while he was visiting my mother and me in the hospital. If missiles were launched, he would be driven to his waiting B-52 and fly off to drop nuclear bombs on the enemy.” This was the same time that Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker, was arrested for refusing to go to New York City’s air raid shelters when a practice alarm for enemy missiles was sounded. She and others felt that the whole exercise gave an illusion of security. Children in school were told to dive under their desks. Still today, it is a strange and perilous world we inhabit – for a short time. The fact of our mortality, the sureness of dying, sometimes sooner than later, depresses many people, especially if they have no religious faith, and don’t dare believe that we are destined, to use Jesus own words, for a new creation. Woody Allen, the film-maker, has an obsession with death and it pervades much of his work. In his film Manhattan he plays himself, the complete worrywart who thinks the sands in the hourglass of time – his time - are rushing, not trickling, to the bottom. So he tries to cram everything in, and is appalled when his latest love-life tells him she will be gone for six months to France on business. She says it’s really a short time; for him, it’s not. But she goes, life goes on, shadowed by insecurity, and he gives the final speech in the film in a laboratory before a dangling skeleton. It’s not a comic prop; it represents his fear that he will die, could die, anytime, even right now, and before long look like that. The antidote is not just to eat well, exercise, and take vitamins – it is to get a religious faith. Or work at the one you have. We wouldn’t be here – indeed, there would be no Christian churches anywhere – if Jesus did not actually, truly, rise from the dead, convince his apostles that it was really himself, and then tell them to spread the good news. What we often forget that this is what the Father intends for each one of us with only one condition—if we love. Meaning what? Exactly what Jesus said when he summed up all the commandments with the love of God and neighbor. Or rather his questioner summed them up when he asked Jesus how he could enter eternal life. But having said that, and believing it, I am mindful of a remark by Thomas Merton, that to tell people to love one another is like saying Eat Wheaties. He’s right. Unless we understand love the way St Paul described it and the Good Samaritan parable illustrated it, love won’t be much more than a greeting card sentiment. But don’t you also have to have faith? Yes. For instance, believe those words you heard from the prophet today that “the sun of justice will arise with its healing rays.” For us that means the risen Christ. Believe those final words of the gospel: “By patient endurance you will save your lives.” Not this life, which is temporal, mortal. But it’s also a down payment, if you wish, on eternal life. And with all our troubles we are called to enjoy life – food, drink, play, love. Add to the list: games, art, music, flowers, babies, pets. Above all, enjoy each other. It’s a betrayal of God’s plan if our love for those things and people corrupts and leads us astray. This call to joy, despite our troubles and our sure mortality, was put in a poem, no more than a verse, that survived the holocaust. The poet was a little girl who did not survive. But this what she wrote: From tomorrow on I will be sad. Not today. Today I will be glad. And every day, No matter how bitter it may be, I shall say, from tomorrow on I will be sad. Not today.