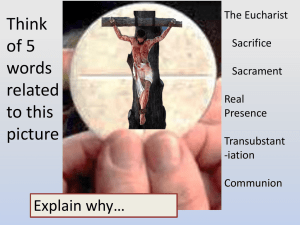

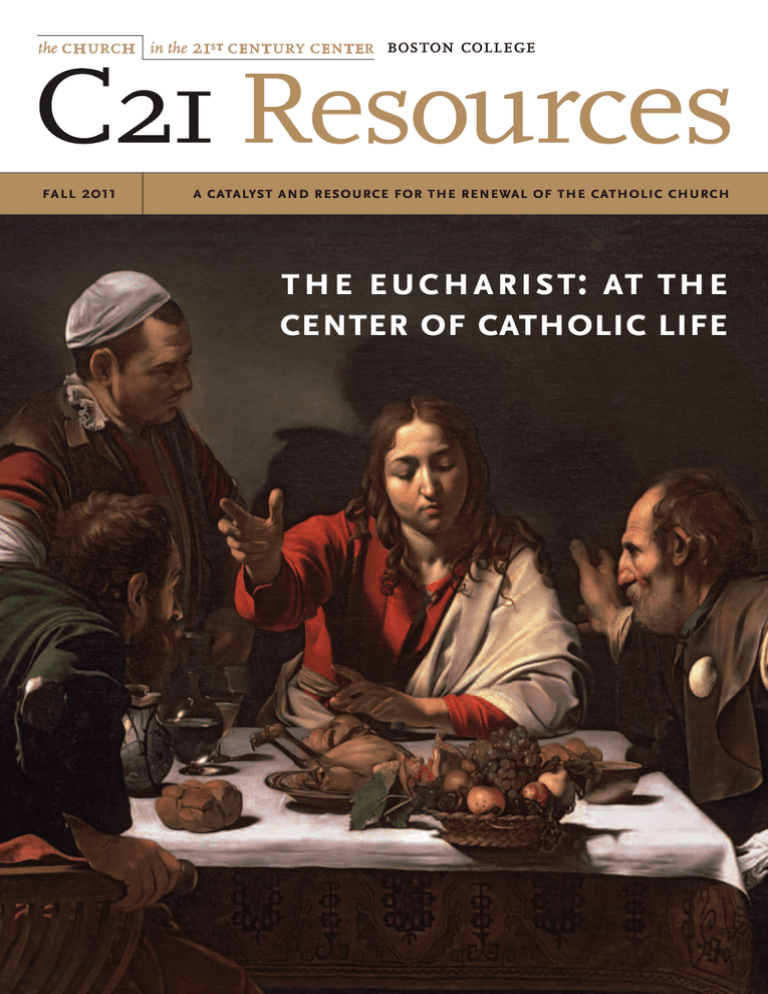

the eucharist: at the center of catholic life church 21

advertisement