A Mathematical Model for the Role of Cell Signal Transduction

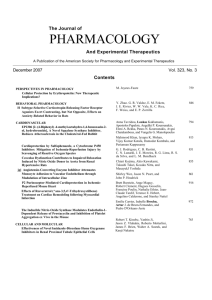

advertisement

Growth Factors, 2002 Vol. 20 (4), pp. 155–175

A Mathematical Model for the Role of Cell Signal Transduction

in the Initiation and Inhibition of Angiogenesis

HOWARD A. LEVINEa,*,†, ANNA L. TUCKERa,†,‡ and MARIT NILSEN-HAMILTONb,{

a

Department of Mathematics, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA; bDepartment of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Molecular Biology, Iowa State

University, Ames, IA, USA

(Received 19 July 2002; Revised 21 November 2002)

Neovascular formation can be divided into three main stages (which may be overlapping): (1) changes

within the existing vessel, (2) formation of a new channel, (3) maturation of the new vessel.

In two previous papers, [Levine, H.A. and Sleeman, B.D. (1997) “A system of reaction diffusion

equations arising in the theory of reinforced random walks” SIAM J. Appl. Math. 683– 730;

Levine, H.A., Sleeman, B.D. and Nilsen-Hamilton, M. (2001b) “Mathematical modelling of the onset

of capillary formation initiating angiogenesis.” J. Math. Biol. 195– 238] the authors introduced a new

approach to angiogenesis, based on the theory of reinforced random walks, coupled with a Michaelis –

Menten type mechanism which views the endothelial vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF)

receptors as the catalyst for transforming into a proteolytic enzyme in order to model the first stage.

It is the purpose of this paper to present a more descriptive yet not overly complicated mathematical

model of the biochemical events that are initiated when VEGF interacts with endothelial cells and

which result in the cell synthesis of proteolytic enzyme. We also delineate via chemical kinetics, three

mechanisms by which one may inhibit angiogenesis (inhibition of growth factor, growth factor receptor

and protease function).

Keywords: Neovascular formation; Angiogenesis; Promoter mechanisms; Inhibitor mechanisms

INTRODUCTION

The cell, as the smallest denominator of living organisms

capable of independent life, takes in and metabolizes

nutrients that are used for its maintenance, movement and

reproduction. In the context of a multicellular organism,

cells must also use nutrients to synthesize signals that are

released and that regulate the activities of other cells.

An extraordinary number of metabolic pathways, signal

transduction cascades and other regulatory elements

are required for a cell to synthesize the macromolecules

necessary for life and to coordinate its own activities. One

has only to confront a diagram as can be found on page

415 of Voet and Voet (1995) to obtain a sense of the

complexity of cellular metabolism.

Many more synthetic and regulatory mechanisms

are involved in maintaining the tightly coordinated and

cooperating multicellular entity that we refer as the body.

Deviation in this cellular community called the body from

the normal tightly organized and cooperating mode can

result in one of the many forms of degeneration known as

disease.

In tumor angiogenesis also, there are several pathways

by which an avascular tumor may induce the endothelial

cell lining of a nearby capillary to break through the

capillary lamina and grow toward the tumor. See Folkman

(1992), and the review article of Z.C. and Y. (1999) for

example. Two excellent review articles by Paweletz and

Knierim (1989) and Rakusan (1995) provide the reader

with an introduction to tumor angiogenesis.

*Corresponding author. Department of Mathematics, 410 Carver Hall, Ames, IA 50011, USA. Tel.: þ1-515-294-8145. Fax: þ 1-515-294-5454.

E-mail: halevine@iastate.edu

†

The authors were supported by NSF grant DMS-98-03992.

‡

E-mail: atucker@iastate.edu

{

E-mail: marit@iastate.edu

All figures in this article were generated using Matlab 6.0. In Figures 2AP1, 4AP1, 8AP1, the precision on the z-axis is greater than the resolution

allowed by the Matlab graphics package. The package allows a display of no more than four or five significant digits before rounding or rescaling. The

result is to be expected since S0 represents the total concentration of available resources and far exceeds what is necessary to open the capillary wall.

ISSN 0897-7194 print q 2002 Taylor & Francis Ltd

DOI: 10.1080/0897719031000084355

156

H.A. LEVINE et al.

It is the purpose of this article to study one of the pathways

by which growth factor is “converted” into protease, namely

the MAP kinase pathway, and to present a somewhat more

detailed kinetic mechanism for the “conversion” of growth

factor into protease by endothelial cells than the simplified

mechanism that was utilized by Levine and Sleeman (1997)

and Levine et al. (2001b; 2003). The mechanism on which

we focus is illustrated in Fig. 2 of Eckhard (1999) and

which may be viewed at www.hosppract.com/issues/1999/

01/eckhardt.htm. A molecule of vascular endothelial cell

growth factor (VEGF) binds to a cell surface receptor and

initiates a cascade of events within the cell cytoplasm and the

cell nucleus which results in the production of several

molecules of proteolytic enzyme as well as in a receptor of

the same type that was bound to the growth factor in

the first place. Two excellent articles by Kyriakis and

Avruch (2001) and Takai et al. (2001) review the MAPkinase pathway.

The MAP kinases constitute an important signaling cascade that regulates transcriptional and metabolic activity.

This group of protein kinases is organized as a multi-protein

complex associated with one or more scaffold proteins.

Activation of the first kinase, Raf, is achieved by the

monomeric G-protein Ras, which is in turn activated by

growth factor receptors that are bound to their respective

growth factor ligands. Activated Raf phosphorylates and

activates ERK (MAP kinase–kinase) which then phosphorylates and activates MAP kinase. MAP kinase phosphorylates and activates transcription factors such as AP-1 that

interacts with DNA and stimulates specific gene expression.

The full mechanism (or at least a substantial part of it

that is already understood) is outlined in the appendix to

this paper. The reader will see that the kinetics discussed

in the appendix lead to a system of at least thirty ordinary

differential equations that describe the chemical kinetics

of this pathway. Several difficulties arise with the use of

such a system of ordinary differential equations to replace

the simple model used by Levine and Sleeman (1997) and

Levine et al. (2001b; 2003). First, the size of the system

itself is formidable. Secondly, and more importantly, the

kinetic constants involved at most steps are unknown.

There are a number of papers that study the kinetics of

various pieces of this pathway and how they influence cell

signaling. For example, Levchenko et al. (2000) focused

their attention on how the scaffold proteins affect protein

1,2

kinase signaling.

THE PROPOSED MECHANISM

Levine and Sleeman (1997) and Levine et al. (2001b; 2003),

presented a simplified model for the interaction of angiogenic

growth factors such as VEGF with growth factor receptors

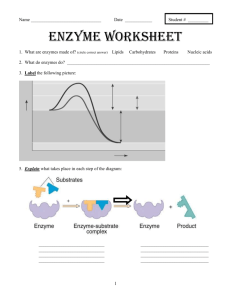

on the surface of endothelial cells as follows (Fig. 1).

If V denotes a molecule of angiogenic factor (substrate)

and R denotes some receptor on the endothelial cell wall,

they combine to produce an intermediate complex, RV

which is an activated state of the receptor that results in the

production and secretion of proteolytic enzyme, C, and a

modified intermediate receptor R0 . The receptor R0 is

subsequently removed from the cell surface after which it

is either recycled to form R or a new R is then synthesized

by the cell. It then moves to the cell surface.3

Likewise, the proteolytic enzyme molecule, C, moves

to the exterior of the cell surface where it degrades the

laminar basement membrane leaving products F0 by acting

as a catalyst for fibronectin degradation. The products F0

need not concern us here.4 We used classical Michaelis–

Menten kinetics for this standard catalytic reaction.

1

The model presented here views the endothelial cell as the minimal subdivision of a tissue that participates in the process of building a capillary.

As such, the cell is the recipient of a growth factor-generated signal to which it responds by movement. Movement is driven by the release of active

protease. The model takes advantage of the fact that any biochemical pathway, no matter how complex, which is defined only by the input (e.g. growth

factor–receptor complex) and the product (e.g. active protease), can be described by a single rate constant that is defined by the rate-limiting step in the

pathway. The model is not designed to describe or to contribute to an understanding of signal transduction. Although currently descriptive, is expected to

contribute to an understanding of cell behavior. It is also anticipated by the authors that the model might become more complex with the addition of more

elements such as other growth factors and inhibitors of angiogenesis as these become better defined by experimental analysis. However, the strength of

the model is that, in its simplicity and without the inclusion of many “correction factors”, it describes many aspects of angiogenesis quite faithfully.

2

The model as presented here, does not yet include the possibility of stem cells adding to the source of new endothelial cells within the tumor. We are

currently developing this aspect of the model. Like experimental research, model building is incremental. The current model provides a flexible platform

for the incorporation of currently known and future discoveries of cellular events in angiogenesis with the hope and expectation that, as these are

incorporated, the model will more accurately describe the biological reality and will provide important predictions that can help the development

of angiogenesis research.

3

Whereas, the model would seem to suggest that a single form of growth factor interacts with a single receptor type, that is not the intent. There are

many isoforms of VEGF, other growth factors, and many receptors that can signal endothelial cells to undergo angiogenesis. Although it could be

expanded to include specific growth factor–receptor interactions, we have instead decided to maintain a simpler mathematical form in which each

element of the model is viewed as a weighted composite of all constituents of that type. For example, all growth factors that induce angiogenesis and their

cognate receptors are represented by the terms V and R, respectively. Similarly, fibronectin (F) represents a composite of extracellular matrix molecules

such as laminin and collagen for example. The equilibrium constants k1 and k21 can be viewed as representing a composite of growth factor– receptor

interactions. In future versions of the model when more is known about local concentrations of particular growth factors and their receptors in specific

tissues, the model might be expanded, for particular situations such as in different tissues, to include the most predominant growth factors.

Although events such as receptor dimerization or oligomerization and growth factors that exist as disulphide linked homodimers are not included

in the model, knowledge of these events influences the effective concentration of receptor and growth factor that is entered into the calculations.

When more complete data is available regarding receptor and growth factor concentrations in tissues in which angiogenesis occurs, we expect to

update our input values based on the current mechanistic understanding of the particular growth factors, their receptors and how they interact.

4

Some of these products contribute to a negative feedback loop that should ordinarily be included in the kinetic equations we derive here.

However, since we understand that the concentrations of these products contribute to the inhibition of angiogenesis, including terms involving

them in our kinetics adds nothing to our understanding of the mathematical processes involved and only further complicates the dynamical

equations. We are planning a paper on plasmin– plasminogen activator/PAI dynamics in which will address this particular point.

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

157

FIGURE 1 Schematic diagram for the mechanisms (2.5)– (2.8). In order to simplify the mechanisms, the transport protein Qt was not included in the

mechanism so that C0 and C are the same species in the kinetics for this system. The species notation is given in Table I.

The point of view there was that the receptors at the

surface of the cell function the same way an enzyme

functions in classical enzymatic catalysis. In symbols,

k1

k2 0

k2

where n is the number of protease molecules produced in

response to a single molecule of growth factor. (This

would lead to the production –consumption equations for

protease and growth factor of the form:

V þ R Y RV; RV ! C þ R0 ; R0 ! R;

kð21Þ

ð2:1Þ

l1

l2

C þ F ! CF; CF ! F 0 þ C:

The mechanism was simplified by combining steps

(2) and (3) in the above mechanism as follows:

k1

k2

V þ R Y RV; RV ! C þ R;

kð21Þ

l1

ð2:2Þ

l2

0

C þ F ! CF; CF ! F þ C:

The principle problem with this mechanism is that it

does not reflect the fact that a single molecule of growth

factor signals a cascade of intracellular events that result in

a cellular response that results in several (perhaps

hundreds) of molecules of protease.5 One might be

tempted to replace Eq. (2.2) by

k1

k2

V þ R Y RV; RV ! nC þ R;

kð21Þ

l1

ð2:3Þ

l2

C þ F ! CF; CF ! F 0 þ C:

d½C

d½V

¼ nk2 ½RV ¼ 2n

:

dt

dt

ð2:4Þ

where [Z ] denotes the concentration of species Z in

micro-moles per liter (micromolarity)).

However, such a mechanism is not stoichiometric.

On the other hand, the more detailed mechanism

outlined in the appendix suffers from the drawbacks

mentioned above.

In order to have a relatively simple mechanism that

is stoichiometric, we need to introduce into the model a

source of supply of amino acids from which the

ribosome can direct the assembly into protease and into

cell receptors using the respective mRNA’s as

templates. These amino acids come from the blood

plasma that bathes the endothelial cells on their

lumenal side or through the basement membrane and

from the surrounding tissue on their ablumenal side via

the cell surface transport proteins or directly from those

already found in the cytoplasm.

To describe the mechanism symbolically, we use

the notation in Table I. With these definitions in mind

5

An additional complicating factor is that this mechanism, like most kinetic mechanisms, does not take into account the local environment. Here the

complicating issue is the fact that the number n may depend upon the concentration of growth factor at the cell surface. For example, it was observed that

the concentration of protease is a bimodal function of the concentration of growth factor say ½C ¼ fð½VÞ (Unemori et al., 1992). For the simulations we

present here, we shall assume very low concentrations of growth factor. Then the number n ¼ f0 ð0Þ and can be numerically interpolated from the data

(for example Unemori et al. (1992)). However, this approximation cannot be employed near the tip of a growing capillary as it marches toward a source

of high concentration of growth factor since f([V ]) is not a linear function of [V ] for large [V ].

158

H.A. LEVINE et al.

TABLE I Notation

Species

Notation

Amino acids

Transport protein

Amino acid—transport protein complex

Amino acids

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Receptor–VEGF complex

Invaginated and degraded VEGF

G-protein activated [RV ] complex

Surface receptor

Total available extracellular protease

Basement lamina protein

X

Pt

X Pt

Y

V

RV

V*

R^

R

C

F

k1

k2

kð21Þ

kð22Þ

ð2:5Þ

k3

½X ¼ sðtÞ

½Pt ¼ pðtÞ

½XPt ¼ lðtÞ

½Y ¼ yðtÞ

½V ¼ vðtÞ

½RV ¼ mðtÞ

½V* ¼ v* ðtÞ

^ ¼ r^ ðtÞ

½R

½R ¼ rðtÞ

½C ¼ cðtÞ

½F ¼ f ðtÞ

Tissue and plasma

Trans-membrane

Cell cytoplasm

Cell cytoplasm

Extracellular matrix

Cell surface and lipid bilayer

Cell cytoplasm

Cytoplasm

Trans-membrane

Extra cellular matrix

Basement lamina

k5 ðtÞ ¼ kHðt 2 t0 Þ

which describes the transport of amino acids to and from

the exterior of the cell through the lipid bilayer and into

the cell cytoplasm6 (The technical term for this is

“facilitated diffusion”). Next, growth factor interacts with

the EC cell receptor

k4

^

V þ R Y RV; RV ! V* þ R;

Source/location

It is important to note that all of the k0 s in the above

mechanism are constant except for k5. We take k5 to be

time dependent and of the following form:

we write:

X þ Pt Y XPt ; XPt Y Y þ Pt ;

Concentration

ð2:9Þ

where H(x) denotes the Heaviside function

(

1; if x $ 0;

HðxÞ ¼

0; if x , 0

and where t0 is the mean time of the endothelial cell

protease response to growth factor. It can be estimated

that the EC begin the production of protease

approximately 15 –20 h after the growth factor ligand

binds with the cell receptor. In the Appendix below we

have attempted to list some of the mechanistic steps

responsible for this delay.8

Finally this protease degrades the proteins of the

basement lamina and the extracellular matrix:

ð2:7Þ

kð23Þ

which roughly describes the endocytosis of the RV complex

with the resultant cellular destruction of growth factor and

^

the production of a G-protein activated intermediate, R:

^

Next, R initiates events that result in the assembly of

intracellular amino acids into intracellular protease which

is then converted to extracellular protease.7

0

k5 ðtÞ

k5 ðtÞ

R^ þ Y ! nC0 þ R; C0 ! C:

l1

l2

C þ F Y CF; CF ! F 0 þ C:

ð2:10Þ

lð21Þ

We combine these two steps in a single equation:

k5 ðtÞ

R^ þ Y ! nC þ R:

where the total available protease is given by

ð2:8Þ

½Ctotal ¼ ½C þ ½CF ¼ ½C0 :

6

The mechanism (2.5) can be viewed as a shortened version of a mechanism for the two way flux of cationic amino acids across a plasma membrane

discussed by White and Christensen (1982; 1983). In the first of these references the authors report that, on the basis of kinetic analysis, “the inward and

outward transport of cationic amino acids through the plasma membrane of fibroblasts and HTC cells is mediated mostly by a single saturable transport

system. . ..” They also report that “the mediated arginine influx is half maximally saturated at an external substrate concentration of 0.1– 0.2 as high as

the apparent intracellular concentration that half maximally saturates the efflux.” This leads us to an estimate for K e ¼ k1 k2 =kð21Þ kð22Þ < 15:0 for the

value of the equilibrium constant when Eq. (2.5) is in equilibrium. The mechanism used by White and Christensen (1982; 1983) which describes the

iso-uni-uni transport system across the cell membrane has the form:

k1

kð23Þ

k2

kð21Þ

k3

kð22Þ

X þ P1t Y Z; P1t Y P2t ; Z Y Y þ P2t :

ð2:6Þ

(See, Segel (1975) for a very thorough treatment of the whole issue of enzyme kinetics in addition to the present mechanism). Here Z ¼ XP1t ¼ YP2t

represents the intermediate while the second equation represents the exchange of extracellularly oriented transport protein P1t with intracellularly

oriented protein P2t (Notice that in the first and third of these reactions, the arrows pointing from the extra-cellular to the intracellular side of the

membrane have rate constants with positive subscripts, while those pointing in the other direction have negative subscripts. In the second, the convention

is reversed). When Eq. (2.6) is in equilibrium, the equilibrium constant is K e ¼ k1 k2 k3 =kð21Þ kð22Þ kð23Þ ¼ ½Y=½X: Mechanism (2.5) is is a condensed

version of Eq. (2.6). When the forward and reverse rate constants in the second step of Eq. (2.6) are the same, this expression for Ke reduces to ours.

7

The model includes the requirement for activation of proteases from latent forms. This is because, as discussed previously, a biochemical

pathway can be represented by the single rate-limiting step (k2) that occurs between the input (growth factor–receptor complex) and output

(active protease). The rate-limiting step could be the very last in this pathway to generation of active protease which is activation of latent

protease, or it could be an earlier step such as rate of protein synthesis or rate of secretion. The model does not limit the choice of which step is

rate limiting. This will be determined by the results from experimental analyses.

8

The use of generic intermediates such as Y and the introduction of “delays” such as we have done above is not uncommon in modeling

biochemical kinetics. In particular, Lev Bar-Or et al. (2000), have presented a kinetic model for the p53-Mdm2 feedback loop which employs

both of these devices.

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

If the total protease were constant, then we could write

(in the absence other sources of basement lamina proteases)

d½F

K cat ½C0 ½F

¼2

dt

K m þ ½F

where Michaelis– Menten kinetics applies. However, in

our case, [C ]0 is not fixed. We will replace it by the total

concentration of protease that results from step (2.10) as a

function of time. Levine et al. (2001a) have carried out a

careful justification for this. (K cat ¼ l2 and K m ¼

ðlð21Þ þ l2 Þ=l1 Þ:

The variables in Table I that are of interest to us are

v; c; r; r^; f : In addition we will need notation for the

endothelial cell density. This we introduce later.

A set of chemical equations such as (2.5) –(2.8)

generally does not take into account other influences on

species concentrations, such as crowding or dispersion.

For example, the transport proteins and other components

of an endothelial cell will become more concentrated in

three-dimensional space as the local cell density increases.

To account for this geometric effect, we will include a

term C r 0 ðtÞ in the rate equation for the transport protein

density. This is the number of additional micromoles per

liter per unit time by which the concentration of transport

protein is increased due to crowding or dispersion (Levine

et al., 2001a). We assume that Cr ð0Þ ¼ 0:

The Law of Mass Action applied to the chemical

equations (2.5) –(2.8) yields9

›s

¼2k1 sðtÞpðtÞþkð21Þ lðtÞ;

›t

›p

¼2kð22Þ yðtÞpðtÞ2k1 sðtÞpðtÞþðkð21Þ þk2 ÞlðtÞþC r 0 ðtÞ;

›t

›l

¼k1 sðtÞpðtÞþkð22Þ yðtÞpðtÞ2ðkð21Þ þk2 ÞlðtÞ;

›t

›m

¼k3 rðtÞvðtÞ2ðkð23Þ þk4 ÞmðtÞ;

›t

›y

ð2:11Þ

¼k2 lðtÞ2k5 ðtÞ^r ðtÞyðtÞ2kð22Þ yðtÞpðtÞ;

›t

›v

¼kð23Þ mðtÞ2k3 rðtÞvðtÞ;

›t

›r

¼k5 ðtÞ^r ðtÞyðtÞþkð23Þ mðtÞ2k3 rðtÞvðtÞ;

›t

›r^

¼k4 mðtÞ2k5 ðtÞ^r ðtÞyðtÞ;

›t

›c

¼nk5 ðtÞ^r ðtÞyðtÞ2 mcðtÞ

›t

159

(The quantities of amino acids resulting from growth

factor degradation are assumed to be negligible in

comparison to the quantities of amino acids from the

surrounding tissue and blood plasma needed to assemble

protease. Thus the rate equation for this quantity is omitted

from the above list).

In the last of the equations above we have included

the term 2 mc which models protease decay. The half

life, ln 2/m, is fairly small.

Suppose the initial value of growth factor is v0 ¼ 0:

Then the above mechanism will not induce any protease.

In this case, we may assume that the mechanism of

amino acid transport, Eq. (2.5) is in equilibrium and the

concentrations of X; Y; P; L are all constants. Calling them

s0, y0, p0, l0 we have

y0 ¼

k 1 k 2 s0

¼ K e s0 ;

kð21Þ kð22Þ

ð2:12Þ

ðk1 s0 þ kð22Þ y0 Þp0 k1 s0 p0

¼

:

l0 ¼

kð21Þ þ k2

kð21Þ

Representative values of the rate constants and

ptotal ¼ p0 þ l0 ; s0 may be found from the literature.

Some of them are given in our simulations below.

In all cases, when cð0Þ ¼ 0 we have the following

conservation laws where r0 is the number of available

growth factor receptors:

ðt

1

0

0

sðtÞ þ yðtÞ ¼ s0 þ y0 2 cðtÞ þ m cðt Þdt ;

n

0

pðtÞ þ lðtÞ ¼ p0 þ l0 þ C r ðtÞ;

ð2:13Þ

r^ðtÞ þ rðtÞ þ mðtÞ ¼ r^0 þ r 0 þ m0 ;

r^ðtÞ þ vðtÞ þ mðtÞ ¼ r^0 þ v0 þ m0 2

ðt

1

cðtÞ þ m cðt0 Þdt0

n

0

where m0 ; r^0 are constants of integration.10

Our analysis will be simplified considerably if we

assume that the concentrations of the intermediates X Pt

and RV are nearly constant, i.e. that X is in excess and

either R is excess relative to V or vice versa, so that

lðtÞ ¼

sðtÞpðtÞ yðtÞpðtÞ

rðtÞvðtÞ

þ ð22Þ ; mðtÞ ¼

;

1

Km

Km

K 2m

ð2:14Þ

9

Partial time derivatives are used here in anticipation of the material in the sequel in which the concentrations will also exhibit dependence on spatial

variables.

10

In the case that n depends upon the local concentration of of v, n ¼ nðvÞ say, then the quantity

ðt

1

cðtÞ þ m cðt0 Þ dt0

n

0

must be replaced by the expression

ðt cðtÞ

mcðt0 Þ n0 ðvðt0 ÞÞvt ðt0 Þcðt0 Þ0

þ

þ

dt0

0

2

0

nðvðtÞÞ

n ðvðt ÞÞ

0 nðvðt ÞÞ

in Eq. (2.13) and every equation containing the former expression which follows from this. That n depends on v can be seen experimentally in the articles

of Unemori et al. (1992) and Wang and Keiser (1998). From the point of view of an individual cell, one cannot assert that n(v) molecules of protease will

be produced for a single molecule of growth factor. However, the reader should understand, that we are dealing with ensemble averages here, as is the

case in all cases involving chemical kinetics. That is, we are not dealing with individual cells but with cell densities and viewing cells in the same spirit as

one views electrons, i.e. as a probability density.

160

H.A. LEVINE et al.

ð22Þ

where we have set K 1m ¼ ðkð21Þ þ k2 Þ=k1 ; K m

¼

2

ðkð21Þ þ k2 Þ=kð22Þ ; and K m ¼ ðk4 þ kð23Þ Þ=k3 : (We are

assuming reaction (2.5) involving transport proteins is of

Michaelis –Menten type in that the concentration of the

intermediate does not vary much in time. We also assume

that Eq. (2.7) enjoys a similar property in so far as

the first equation in that pair is concerned. This involves

the assumption that the growth factor is present in very

low concentrations relative to the number of available

receptors). (Notice that Eq. (2.14) forces the choice

m0 ¼

r 0 v0

K 2m

ð2:15Þ

upon us).

Some routine algebra leads to the following system

of algebraic and differential equations:

ðt

1

cðtÞ þ m cðt0 Þ dt0 ;

y 2 y0 ¼ ðs0 2 sÞ 2

n

0

zðtÞ ¼

sðtÞ

yðtÞ

þ ð22Þ ;

1

Km Km

r ¼ r 0 þ v 2 v0 þ

ðt

1

cðtÞ þ m cðt0 Þ dt0 ;

n

0

However, we want to model the impact of these

variables on cell movement and tissue degradation, i.e. on

h, f where h is the cell density and f is the density of the

capillary wall proteins.

Thus two problems remain. First, we must relate the

crowding of the transport proteins to the endothelial cell

density and second, we need two more equations that

relate h, f to s; y; c; v; r; r^:

The first task is relatively easy. We write p0total ¼

p0 þ l0 ¼ d0 h0 where p0total is the total available number

of transport proteins per cell. d0 is the density (in micromoles per liter) of transport proteins on the surface of

endothelial cells in a normal capillary. We then write

p0 þ l0 þ C r ðx; tÞ ¼ dðx; tÞhðx; tÞ < d0 hðx; tÞ:

The second task is more complex. We need the rate

equation for the protein (loosely designated as fibronectin)

density of the basement lamina. This is a complex

structure made up primarily of fibronectin and various

other collagens. The differential equation used by Levine

and Sleeman (1997) and Levine et al. (2001b) that

describes the time evolution of this protein density is:

›f

4f

¼

›t T f

r 0 þ v þ K 2m

ðv0 2 vÞ

ð2:16Þ

K 2m

ðt

K 2m þ v 1

0

0

cðtÞ þ m cðt Þ dt ;

2

n

K 2m

0

›s

k2 sðtÞ kð21Þ yðtÞ p0 þ l0 þ C r ðtÞ

¼ 2 1 þ

;

ð22Þ

1 þ zðtÞ

›t

Km

Km

r^ ¼

12

f

fM

h

K cat cf

2

h0 K m þ f

ð2:18Þ

where now K cat ¼ l2 and K m ¼ ðlð21Þ þ l2 Þ=l1 are the

kinetic constants arising from the second pair of kinetic

equations in (2.3). fM is the density of the BL and Tf is the

logistic growth time.11

The second missing equation is a differential

equation that describes the time evolution of h. This is a

somewhat involved story.

›v

k4

›c

¼ 2 2 vr; ¼ nk5 ðtÞ^ry 2 mc:

›t

›t

Km

where we have suppressed the time variable. We also take

r^0 ¼ 0:

ð2:17Þ

This is just the statement that, initially, there are no

G-protein activated receptors.

Next we imagine endothelial cells distributed along a

capillary of length L in some nonuniform manner.

We view this distribution as one of cell density rather

than as individual cell number. The point of view here is

the same as in quantum mechanics. We are not looking at

individual cells but rather cell density as a probability

density. Therefore, the endothelial cell density (as well as

the other quantities in Table I depend on position as well

as time. Thus, ½VðtÞ ¼ vðx; tÞ; etc. just as was done by

Levine et al. (2001b).

We now have six dependent variables s; y; c; v; r; r^ along

with three differential equations and three algebraic

equations in (2.16).

REINFORCED RANDOM WALK

It is expected that endothelial cells will move into cavities

in the extracellular matrix created by the protease they

express in response to the VEGF stimulus. The point of

view we adopt here is the same as was used by Levine and

Sleeman (1997) and Levine et al. (2001b) and is in marked

contrast to earlier works. Levine and Sleeman (1997) cites

relevant literature and the differences in approach were

spelled out in some detail.

The underlying assumptions (justified in detail by

Levine et al., 2001b) are the following:

(1) The movement of endothelial cells in tissues is not

random but depends upon the local environment of

the cells.

(2) The movement of EC in response to growth factor

is indirect. Endothelial cells will move up a protease

11

In T f < 18 h; fM moles of fibronectin will be generated by h0 endothelial cells (Yamada and Olden, 1978). In the absence of protease, h ¼ h0 where

h0 is the background concentration

of EC in a normal capillary. We assume a logistic growth of fibronectin in this case, i.e. that f t ¼ bf ð1 2 f =f M Þ for

ÐT

some b. Therefore, f M ¼ b 0 f ðtÞð1 2 f ðtÞ=f M Þ dt # f M bT f =4: The inequality will be sharp when b ¼ 4/Tf.

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

gradient (chemotactic movement) in response to

the protease they generate when stimulated by

VEGF. This chemotactic movement is also chemokinetic, i.e. it depends upon the concentration of

protease as well as on its gradient. More precisely,

if the concentration of protease is small, but not too

small, the cells will move up the protease gradient.

However, if the protease concentration is too large,

the protease will destroy the cells (Rous and Jones,

1916). We can interpret this as saying that the

cells will avoid regions where the protease gradient

is too large or by saying that they will move down the

protease gradient in such cases.

(3) Endothelial cells will move down a fibronectin

gradient (haptotactic movement) when the fibronectin density is high and up the fibronectin gradient

when the fibronectin density is small. This is a

rough qualitative statement based on the paper by

Bowersox and Sorgente (1982), where chemotaxis of

endothelial cells in response to fibronectin was

considered.

161

It has been observed that these cells aggregate as their

food supply is consumed, i.e. as the local concentration of

cAMP increases.12 The idea of reinforced (or biased)

random walk seems to have its origins from Davis (1990).

The chemotactic sensitivity functions are phenomenological in character. For example, if the cell motion were

completely random, we take t ðc; f Þ ¼ constant: The above

equations then reduce to the one dimensional diffusion

equation and the cell density will become uniform in x

with time. If the movements depended solely upon the

gradients of c, f, a natural choice might be t ðc; f Þ ¼

const expðacÞ expð2bf Þ where a, b are positive constants.

The sensitivities vanish when t ðc; f Þ is constant, whereas,

in this case, the sensitivities are uniformly positively

correlated ða . 0Þ with protease and uniformly negatively

correlated with fibronectin ð2b , 0Þ:13

The dynamical equation (3.1) then suggests that if c, f

tend to steady state functions c1 ðxÞ; f 1 ðxÞ; the limiting

form of the cell density should be

lim hðx; tÞ ¼ Ae ðac1 ðxÞ2bf 1 ðxÞÞ

t!þ1

The cell movement equation takes the form:

›h

›

›

h

¼D

ln

h

;

›x

›x

t ðc; f Þ

›t

ð3:1Þ

which may be written in the more standard form:

tc cx þ tf f x

ht ¼ Dhxx 2 D h

t ðc; f Þ

x

¼ Dhxx 2 Dðh ðln tÞx Þx :

ð3:2Þ

The function t ðc; f Þ is called the probability transition

rate function. The ratios ›c t ðc; f Þ=t ðc; f Þ and

›f t ðc; f Þ=t ðc; f Þ are known as the chemotactic sensitivity

coefficients for protease and for fibronectin, respectively.

The Eq. (3.1) is sometimes called the continuous form

of the master equation. We shall call it the master

equation. An equation by Othmer and Stevens (1997) was

used as a model for the study of fruiting bodies such as

Myxococcus fulvus and Dictyostelium discoideum

amoeba. There t was a function of the local concentration

of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, a compound excreted

by these amoeba as they consume their local food supply.

where A is some constant of proportionality.

When the movement is chemokinetic as well as

chemotactic, the sensitivity factors will depend on c, f.

It seems reasonable to assume that cell movement will

be very sensitive to small concentrations of protease

and will be positively correlated with the enzyme

concentration. It is known that, in the presence of large

concentrations of protease, the cells will be degraded

and hence their movement will cease.

Likewise, it is reasonable to assume that cell movement

will be sensitive to low, but not too low, fibronectin

densities and insensitive to high fibronectin densities.

(If the fibronectin density is too low, the cell pseudopodia

have nothing to which to attach themselves so that they

can pull the cell along. On the other hand, if the fibronectin

density is too high in a region, then the cells cannot invade

that region. This has been documented in the literature by

Terranova et al. (1985).)

This suggests that we should take t ðc; f Þ ¼ t1 ðcÞt2 ð f Þ

since these movements should be independent.

We could take the protease sensitivity to be of the form:

t1 0 ðcÞ

g1

¼

;

t1 ðcÞ a1 þ c

12

In Levine et al. (2000), some of the mathematical properties of the solutions of the problem obtained numerically by Othmer and Stevens (1997)

were elucidated.

13

The phrase “h is positively correlated with c” is defined as follows. Consider the first order partial differential equation U t þ ½t0 ðvÞvx =t ðvÞU x ¼ 0

where U, v are functions of (x, t) (In the present context think of U ¼ h, v ¼ c and t 0 ðvÞ=tðvÞ as the chemotactic sensitivity). We say U is positively

correlated with v at a point (x, t) if the characteristic of the pde U t þ ½t 0 ðvÞvx =tðvÞU x ¼ 0 at (x, t) has positive slope if vx ðx; tÞ is positive and the

characteristic has negative slope if vx ðx; tÞ is negative. The correlation will be positive if the sensitivity t0 ðvÞ=tðvÞ is positive, negative if the sensitivity is

negative, and neutral if the sensitivity vanishes. When the sensitivity coefficient is constant, we say the correlation is uniform. The geometric meaning is

that when U is positively correlated with v, then “U will transported to the right when v is increasing and to the left when v is decreasing.” Thus if v

depends only upon x and has a single positive maximum, U will tend to aggregate at the point where the maximum occurs. Similarly, if U is negatively

correlated with v, then and v has a minimum, U will aggregate at the point where the minimum occurs.

An interesting situation arises when the sensitivity changes sign. For example, suppose t 0 ðvÞ=tðvÞ ¼ 1 2 v and vðxÞ ¼ 1 þ ð2=pÞtan21 x so that

x ¼ 0 is an inflection point for v. Then ð1 2 vÞvx is positive for x , 0 and negative for x . 0: Therefore, U will be positively correlated with v

for x , 0 and negatively correlated with v for x . 0: Thus U will aggregate at the inflection point of v, namely x ¼ 0:

162

H.A. LEVINE et al.

TABLE II Simulation parameters

Variable name

Units

26

Microns 10 m

Hours

Micro-moles/liter mM

mM

mM

mM

mM

mM

mM

Cells/liter

mM

mM h21

Position

Time

Growth factor concentration

Receptor density

Receptor–VEGF complex

Extracellular protease

Extracellular resources

Intracellular resources

Basement lamina protein

Endothelial cell (EC) density

Inhibitor concentrations ð j ¼ v; r; cÞ

Inhibitor source rates ð j ¼ v; r; cÞ

so that for the protease probability transition rate function

factor,

t1 ðcÞ ¼ Aða1 þ cÞg1

t1 ðcÞ ¼ Aða1 þ cÞg1 ða2 þ cÞ2g1 :

However, this does not convey the full thrust of item 2

above.

A more systematic way to proceed is to consider the

biology more closely. A protease sensitivity function

should have compact support contained in some interval

½0; c0 Þ vanish at the ends of this interval, and have a unique

positive maximum at some point cmax.

Then, not only will the sensitivity change sign near the

maximum of this function, the cells will tend to aggregate

near the maximum value of this function and de-aggregate

near the ends of the interval. That is, h will be positively

correlated with c for c , cmax and negatively correlated

with c for c . cmax : As the value of c approaches the end

values, 0, c0, the contribution of protease to cell movement

will become negligible if the sensitivity vanishes near the

end points.14

Because simulations will involve computation of

t1 0 ðcÞ=t1 ðcÞ; we relax the condition that t1 vanish at the

end points. We take wðcÞ to be a function of the form

described above. Then

ð3:3Þ

where a and g are positive constants chosen such that a g is

very small. Then the chemotactic sensitivity function

becomes:

0

Dimensionless variable

x

t

vðx; tÞ

rðx; tÞ

r^ ðx; tÞ

cðx; tÞ

sðx; tÞ

yðx; tÞ

f ðx; tÞ

hðx; tÞ

ij ðx; tÞ

isj ðx; tÞ

x0 ¼ x=L

t0 ¼ t=T

Vðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ vðx; tÞ=r0

Rðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ rðx; tÞ=r 0

^ 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ r^ ðx; tÞ=r 0

Rðx

Cðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ cðx; tÞ=r 0

Sðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ sðx; tÞ=s0

Yðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ yðx; tÞ=s0

Fðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ f ðx; tÞ=f M

Nðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ hðx; tÞ=h0

I j ðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ ij ðx; tÞ=r 0

I sj ðx 0 ; t0 Þ ¼ ij ðx; tÞT=r0

The choice for f is similar. Specifically, if we take cð f Þ

to be a function of the form described above, then

t2 ð f Þ ¼ ½a 0 þ c ð f Þg

where a1 is a small positive constant. However, we really

do not expect the probability rate to become infinite as c

ranges over all positive numbers. This suggests that we

take t1 as we did earlier (Levine and Sleeman, 1997;

Levine et al., 2001b) namely:

t1 ðcÞ ¼ ½a þ wðcÞg ;

Dimensioned variable

ð3:4Þ

ð3:5Þ

where a0 , g 0 are positive constants chosen such that the

product a0 g0 is very small. Then the haptotacic sensitivity

function becomes:

t2 0 ð f Þ

g 0c 0ð f Þ

¼

t2 ð f Þ a þ c ð f Þ

ð3:6Þ

Beyond this, the functional forms of f, c must be

determined experimentally although we may always

normalize them so that they take values in ½0; 1:

The larger the constant g (resp. g 0 ) is, the more concentrated about the value cmax (resp. fmax) the EC density

will be.

The specific choices we take are given in the section on

simulations.

Remark 1 This is a somewhat different philosophical approach than we took earlier (Levine and Sleeman

1997; Levine et al., 2001b). However, we believe that

this approach more accurately reflects the underlying

biology.

THE SYSTEM IN ONE DIMENSION

The system of dynamical and algebraic equations for

s; y; c; v; h; r; r^; f consists of the equations (2.16), (2.18),

(3.1), (3.3) and (3.5).

We assume initial conditions for the five differential

equations on an interval ½0; L as follows:

sðx; 0Þ ¼ s0 ; hðx; 0Þ ¼ h0 ; cðx; 0Þ ¼ 0;

0

t1 ðcÞ

gw ðcÞ

¼

:

t1 ðcÞ a þ wðcÞ

0

ð4:1Þ

f ðx; 0Þ ¼ f M ; vðx; 0Þ ¼ v0 ðxÞ;

14

The requirement that t1 have compact support can be relaxed. For example, we might consider t1 ðcÞ ¼ Ac m expð2ac n Þ rather than

t1 ðcÞ ¼ Ac m ðc0 2 cÞn : The positive constants in both forms must be determined empirically.

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

where v0 ð·Þ will approximate a constant multiple of

unit impulse (“delta”) function. The question of

smoothness is not an issue here. The precise form

used is given in equation (7.1) below.

We write the system in dimensionless variables,

length and time scales to be selected later.

Then the system of equations to solve becomes:

!

ð t0

l1

Y ¼ Ke þ 1 2 S 2

Cðx0 ; t0 Þ þ m Cðx0 ; s0 Þ ds0 ;

n

0

the

its

we

the

ZðtÞ ¼ zðtÞ ¼ s1 SðtÞ þ sð22Þ YðtÞ;

!

ð t0

1

0 0

0 0

0

Cðx ; t Þ þ m Cðx ; s Þ ds ;

R ¼ 1 þ V 2 Vðx ; 0Þ þ

n

0

0

R^ ¼ ð1 þ l2 þ l2 VÞðVðx0 ; 0Þ 2 VÞ 2 ð1 þ l2 VÞ

"

!#

ð t0

1

Cðx0 ; t0 Þ þ m Cðx0 ; s0 Þ ds0 ;

£

n

0

r0 N

›S ;

¼ 2k2 s1 SðtÞ þ kð21Þ sð22Þ YðtÞ

0

1þZ

›t

›V

¼ 2k4 l2 RV;

›t 0

›C

^ 2 mC;

¼ n k5 ðt0 ÞRY

›t 0

›F

4

K cat l3 CF

;

¼

Fð1

2

FÞN

2

1 þ rf F

›t0 T f

›N

›

›

N

¼ D 0 N 0 ln

;

›x

›x

TðC; FÞ

›t 0

ð4:2Þ

163

TABLE III Dimensionless parameters

Initial growth factor

Vðx0 ; 0Þ ¼ vðx; 0Þ=r0

Dimensionless cell movement (diffusivity)

constant

Dimensionless protein decay rates

where mj is one of m, miv, mir, mic

Dimensionless inhibitor equilibrium constants

where nej is one of neiv ; neir ; neic

Dimensionless kinetic constants ki

where ki is one of k; kð22Þ ; k2 ; k4

Dimensionless kinetic function k5(t)

Dimensionless delay time t00

First renormalized initial receptor density

Second renormalized initial receptor density

Third renormalized initial receptor density

Normalized initial amino acid density

Normalized initial amino acid density

Normalized initial transport protein density

Normalized maximum “fibronectin” density

Dimensionless”fibronectin” time

Dimensionless Kcat

D ¼ TD=L 2

mj ¼ mj T

nej ¼ r0 nje

ki ¼ k i T

k5 ðt0 Þ ¼ T s0 k5 ðtÞ

t0 0 ¼ t0 =T

l1 ¼ r 0 =s0

l2 ¼ r 0 =K 2m

l3 ¼ r 0 =K m

s1 ¼ s0 =K 1m

sð22Þ ¼ s0 =K ð22Þ

m

r0 ¼ d0 h0 =s0 Þ

rf ¼ f M =K m

T f ¼ T f =T

K cat ¼ T K cat

micro moles per liter per hour and that the amino acid

concentration in the plasma is varying at a rate of sr ðtÞ

micro moles per liter per hour (This assumes that the

amino acids are “well mixed” while there is a spatial

distribution of growth factor). If these are written in

non dimensional variables, then with V r ðx0 ; t0 Þ ¼

Tvr ðLx0 ; Tt0 Þ=r 0 and Sr ðt0 Þ ¼ Tsr ðTt0 Þ=s0 the system (4.2)

is to be replaced by

!

ð t0

l1

0 0

0 0

0

Cðx ;t Þþ m Cðx ;s Þds

Y ¼K e þ12S2

n

0

ð t0

þ Sr ðs0 Þds0 ;

0

where TðC; FÞ ¼ tðr 0 C; f M FÞ: The sensitivity constants

ai ; bj may be redefined so that T is independent of the

scale factors r 0 ; f M . The astute reader will notice that we

cannot scale away n as the ratio C/n does not appear in the

fibronectin equation or in the cell movement equation.

This is the critical point of this paper. If n is large, the

decay in fibronectin will be very large even if v is small.

Likewise, the cell movement will be surprisingly large in

spite of the presence of only a small amount of growth

factor. Boundary conditions are needed only for the last of

the above equations. The no-flux conditions:

›

N

›

N

N 0 ln

¼ N 0 ln

›x

TðC; FÞ x0 ¼0

›x

TðC; FÞ x0 ¼1

¼0

ð4:3Þ

will suffice for our purposes.

The nondimensionalized initial conditions become:

Sðx 0 ; 0Þ ¼ 1; Nðx 0 ; 0Þ ¼ 1; Cðx 0 ; 0Þ ¼ 0;

Fðx 0 ; 0Þ ¼ 1; Vðx 0 ; 0Þ ¼ v0 ðLx 0 Þ=r 0 :

ð4:4Þ

Remark 2 It may be that growth factor is being applied to

the exterior of the basement lamina at a rate of vr ðx; tÞ

Z ¼ s1 Sþ sð22Þ Y;

R¼1þV 2Vðx0 ;0Þ2

ð t0

V r ðx0 ;s0 Þds0

0

!

ð t0

1

0 0

0 0

0

þ Cðx ;t Þþ m Cðx ;s Þds ;

n

0

0

^

R¼ð1þ

l2 þ l2 VÞ Vðx ;0Þþ

ð t0

!

V r ðx ;s Þds 2V ; ð4:5Þ

0

0

0

0

"

!#

ð t0

1

0 0

0 0

0

Cðx ;t Þþ m Cðx ;s Þds

2ð1þ l2 VÞ

;

n

0

r0 N

›S þSr ðt0 Þ;

¼ 2k2 s1 SðtÞþkð21Þ sð22Þ YðtÞ

0

1þZ

›t

›V

¼2k4 l2 RV þV r ðx0 ;t0 Þ;

›t 0

›C

^ 2 mC;

¼nk5 ðt0 ÞRY

›t 0

›F 4

K cat l3 CF

;

¼ Fð12FÞN 2

0

1þ rf F

›t T f

›N

›

›

N

¼D 0 N 0 ln

:

›x

›x

TðC;FÞ

›t 0

164

H.A. LEVINE et al.

We insert these two source terms for two disparate

reasons. In the application of this work to a

coupled system of ECM-capillary transport equations,

the source term vr ðx; tÞ will be proportional to the

concentration of VEGF molecules that have

diffused across the ECM from a remote source

(See, Levine et al. 2000; 2001b, for an illustration of

this). Also, a tumor cell that has moved away from a

remote tumor and implanted itself just inside the

capillary wall (metastasis) can serve as a source of

VEGF.

The amino acid concentration in the blood is

renewed on some continuing basis. The source

term reflects this renewal. Generally the total available

amino acid concentration will be some periodic

function of time. Tumor secreted growth factor

induces an excess production of protease by

endothelial cells from the blood amino acids that

constitutes a part of the extra burden on the body’s

resources. In particular, the larger n is, the greater is

this burden.

to t0 , we obtain to first order in e :

!

ð t0

l1

0 0

0 0

0

dy¼ 2dsþ

dcðx ;t Þþ m dcðx ;s Þds ;

n

0

!

ð t0

1

0 0

0 0

0

dr ¼ dv2 dv0 þ dcðx ;t Þþ m dcðx ;s Þds ;

n

0

dr^¼ ð1þ l2 Þðdv0 2 dvÞ

"

!#

ð t0

1

0 0

0 0

0

2

dcðx ;t Þþ m dcðx ;s Þds

;

n

0

ðdsÞt0 ¼ ½2k2 s1 dsðtÞþkð21Þ sð22Þ dyðtÞr0 =

£ð1þ s1 þK e sð22Þ ÞðdvÞt0

¼ 2k4 l2 dv;ðdcÞt0 ¼nk5 ðt0 ÞK e dr^2 md

c;ðdf Þt0

¼

K cat l3 dc

24

df þ

;

Tf

1þ rf

› ›C Tð0;1ÞðdcÞx 2 ›F Tð0;1Þðdf Þx

ðdhÞt0 ¼ D ðdhÞxx 2

:

›x

Tð0;1Þ

INSTABILITY ANALYSIS

The system (4.2) together with Eqs. (4.3) and (4.4) can

be viewed as a dynamical system in which we are

perturbing the rest state

^ V; C; F; Nl

Re ¼ kS; Y; R; R;

Thus, dv converges uniformly and exponentially

rapidly to zero. If we assume that, as t0 ! þ1; the

solution of Eq. (5.2) converges to a steady state, then,

suppressing the argument x0

lim kds; dy; dr; dr;^ dv; dc; df ; dhl

¼ k1; K e ; 1; 0; 0; 0; 1; 1l

t0 !1

by perturbing Vðx0 ; 0Þ from zero. As is well known,

theorems that claim stability of rest states from

statements of their linearized stability, are rare and, in

many cases involving nonlinear partial differential

equations, are nonexistent. However, the converse is

true, namely, if the linearized problem is unstable, then

so is the nonlinear problem.

Suppose, as is the case biologically, that Vðx0 ; 0Þ ¼

edv0 ðx0 Þ where e . 0 is small. Then set

^ V; C; F; Nl ¼ k1 2 eds; K e 2 edy;

kS; Y; R; R;

¼ kdse ; dye ; dr e ; re ; dve ; dce ; df e ; dhe l;

ds e ¼

ð1

l1

dce ðxÞ þ m dcðx0 ; s0 Þ ds0 :

nð1 þ K e Þ

0

In order that the integral on the right converge, we

must have dce ðx0 Þ ¼ 0: Thus, for each x0 ,

0

ð5:1Þ

where dg denotes a small perturbation in the quantity g.

Using gt0 to denote partial differentiation with respect

ð5:3Þ

dve ¼ 0 and dye ¼ K e dse : From the first of Eq. (5.2)

we see that

ð1

1 þ edr; edr;^ edv; edc;

1 2 edf ; 1 þ edhl

ð5:2Þ

dcðx0 ; s0 Þ ds0 ¼

ndse ðx0 Þ

:

mðK e þ 1Þ

ð5:4Þ

Ð 1Since0 dc0 e ¼0 0; we must also have dr^e ¼ 0: Therefore,

0 dcðx ; s Þ ds ¼ nð1 þ l2 Þdv0 =m: This gives us an

indication of how much protease we can expect from the

system for small concentrations of growth factor. Setting

ðdf Þt ¼ 0 and using dce ¼ 0 again, we see that df e ¼ 0:

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

Consequently, dhe;xx ¼ 0: Therefore, using the boundary

conditions we conclude that dhe ; 0:

Summing up, we have, together with Eq. (5.4)

dRe ¼ kdse ; dye ; dre ; dr^e ; dve ; dce ; df e ; dhe l

¼ dv0 ð1 þ l2 Þ

l1

K e l1

l2

;

;

; 0; 0; 0; 0; 0 : ð5:5Þ

K e þ 1 K e þ 1 1 þ l2

(The apparent increase in available receptors is an

artifact of the Michaelis – Menten assumption in Eq. (2.14).

We assumed at the outset that r0 receptors were free and

r 0 v0 =K 2m were bound. When all the growth factor is gone

from the system, the number of free receptors returns to its

expected value, r 0 þ r 0 v0 =K 2m (or, in this case, 1 þ edr e )

which is the concentration of free receptors together with

the concentration of receptors that are initially bound up

with the growth factor bolus).

This means that under small perturbations, the

linearized system (5.2) carries the rest state Re to a new

rest state Re þ edRe and hence cannot be stable.

We illustrate this instability in the computations below.

165

We begin with the case of growth factor inhibition.

Thinking of the concentration of each species as both space

and time dependent, the total concentration of growth

factor, vtot, in the system consists of the concentration of

active molecules (va), the concentration of inhibited

molecules vi, the concentration of molecules bound to

receptors m and the concentration of molecules that have

been degraded v

a : If we assume that the rate of supply of

growth factor is vr ðx; tÞ then we have the following

dynamics and conservation laws:

›va

¼ kð23Þ mðtÞ 2 k3 rðtÞva ðtÞ 2 vsa ðx; tÞ;

›t

›m

¼ k3 rðtÞva ðtÞ 2 ðkð23Þ þ k4 ÞmðtÞ;

›t

›r

¼ k5 ðtÞ^rðtÞyðtÞ þ kð23Þ mðtÞ 2 k3 rðtÞva ðtÞ;

›t

›r^

¼ k4 mðtÞ 2 k5 ðtÞ^rðtÞyðtÞ;

›t

ð6:4Þ

›v

a

›vtot

¼ k4 mðtÞ;

¼ vr ðx; tÞ;

›t

›t

vtot ¼ va þ vi þ m þ v

a ;

vi ¼ nve va iv

INHIBITION

One would like to inhibit the production of protease with

some sort of inhibitor. There are, as one sees from the

mechanism described in the appendix below, several

points at which inhibition would be effective.

For example, in the overall mechanisms (2.5) –(2.8),

one might try to inhibit protease production with a

protease inhibitor, or growth factor with a growth factor

inhibitor, or try to block receptor function with a receptor

inhibitor. (Blocking angiogenesis by interfering with

various steps in the signaling pathway is under

consideration at the experimental level. See, Eckhard

(1999) for a nice illustration of some of the steps that are

being selected as possible targets.)

In order to analyze such statements, we argue as

follows:

If I v ; I c ; I r are inhibitor molecules, consider the

equilibria:

Iv þ V A Y V I ;

ð6:1Þ

I r þ RA Y RI

ð6:2Þ

and

I c þ CA Y CI ;

ð6:3Þ

where the subscripts A, I refer to the active and inert forms

of the molecular species to which the subscript is attached.

Let nev ; nec ; ner be the equilibrium constants for each of

these reactions.

where iv is the concentration of inhibitor and where vsa is a

sink term to be determined that describes the effect of the

inhibitor on the growth rate of active receptors. In order to

determine the form of vsa , we take the time derivative of the

seventh equation after using the eighth equation to

eliminate vi and the first equation to eliminate ›t va to obtain

vr ¼ ð1 þ nve iv Þvsa þ va nve ›t iv

þ nve iv ½kð23Þ mðtÞ 2 k3 rðtÞva ðtÞ:

This leads us to:

›

½va ð1 þ nve iv Þ ¼ kð23Þ mðtÞ 2 k3 rðtÞva ðtÞ þ vr ðx; tÞ:

›t

It is convenient to define v ¼ va þ vi ¼ ð1 þ n ev iv Þva

as the free growth factor, i.e. the concentration of growth

factor that is neither receptor bound nor destroyed. Then

the differentiated form of the equations which replace the

last two equations in (2.13):

›

ð^r þ m þ rÞ ¼ 0

›t

ð6:5Þ

›

ð^r þ m þ vÞ ¼ 2k5 r^y þ vr :

›t

These equations are of the same form as the

differentiated form of the last two equations in (2.13)

with the exception that now we have included the

source term for growth factor in the second equation.

166

H.A. LEVINE et al.

Now the second equation in (2.14) takes the form

mðtÞ ¼

rðtÞva ðtÞ

:

K 2m

laws:

ð6:6Þ

We will also need an equation which describes the

time dynamics for the inhibitor:

›iv

¼ isv ðtÞ 2 miv iv :

›t

ð6:7Þ

where, from the point of view of the patient, the half

life, ln 2=miv ; should be large. The initial condition for

Eq. (6.7) may be taken to be iv ðx; 0Þ ¼ i0 ðxÞ (If the

inhibitor is introduced intravenously, we may take

i0 ¼ 0 and isv to be a constant).

We list here only the dimensionless form of the

equations in Eq. (4.5) which must be changed to reflect

the altered dynamics:

R^ ¼

1þ

l2 ð1 þ Vðx0 ; t0 ÞÞ

1 þ nev I v ðx 0 ; t0 Þ

Vðx 0 ; 0Þ þ

£

ð t0

›r a

¼ k5 ðtÞ^rðtÞyðtÞ þ kð23Þ mðtÞ 2 k3 r a ðtÞvðtÞ 2 r sa ;

›t

›m

¼ k3 r a ðtÞvðtÞ 2 ðkð23Þ þ k4 ÞmðtÞ;

›t

›v

¼ kð23Þ mðtÞ 2 k3 r a ðtÞvðtÞ;

ð6:9Þ

›t

›r^

¼ k4 mðtÞ 2 k5 ðtÞ^rðtÞyðtÞ;

›t

r total ¼ r a þ r i þ m þ r^ ¼ r 0 þ m0

r i ¼ ner r a ir

where now r sa is a sink for activated receptors. It is clear that

›

ð^r þ m þ r a Þ ¼ 2r sa ;

›t

›

ð^r þ m þ vÞ ¼ 2k5 r^y þ vr :

›t

ð6:10Þ

From the first of these and the fifth of Eq. (6.9), we

see that we have no choice but to take

!

r sa ¼ ›t r i :

V r ðx 0 ; s0 Þds 0 2 Vðx 0 ; t 0 Þ ;

0

2 1þ

l2 Vðx ; t Þ

Þ

1 þ nev I v ðx0 ; t0 Þ

0

With this choice, we are once again led to:

0

"

!#

ð t0

1

0 0

0 0

0

Cðx ; t Þ þ m Cðx ; s Þ ds

£

;

n

0

›

ð^r þ m þ rÞ ¼ 0;

›t

ð6:8Þ

›V

l2 V

þ V r ðx0 ; t0 Þ;

¼ 2k 4 R

1 þ nve I v ðx0 ; t0 Þ

›t 0

›I v

¼ I sv ðtÞ 2 miv I v :

›t 0

(The equation for R is unchanged from that

Eq. (4.5).) The source term isv has been replaced by

its non dimensional form I sv ðt0 Þ ; T isv ðt0 Þ=r 0 ; iv by

I v ¼ iv =r 0 ; nve ¼ r 0 nve and miv ¼ T miv .

The astute reader will note that the inhibition of V is

expressed by the replacement of l2 by l2 =ð1 þ

nev I v ðx0 ; t0 ÞÞ: As we let nev increase without bound, i.e.

as we drive the equilibrium to the right, this coefficient

will tend to zero. This will drive R to unity and R̂ to

zero and there will tend to be very few activated

receptors to convert intracellular resources into

protease.

We turn next to Eq. (6.2), the case of receptor inhibition.

Here the situation is somewhat similar to the first case.

We have r total ¼ r a þ r i þ m þ r^ ¼ r 0 þ m0 as the concentration of receptors available a very short time after

the reaction has begun (Again, each variable is potentially

a function of position and time). The chemistry dictates

the following dynamical equations and conservation

where now r ¼ r a þ r i ¼ ð1 þ ner ir Þr a denotes the concentration of receptors per cell at time t which are not

bound to growth factor nor part of an activated receptor

complex. The second equation in (2.14) takes the form

mðtÞ ¼

r a ðtÞvðtÞ

:

K 2m

ð6:11Þ

The altered dynamical equations are of the same form

as given in Eq. (6.8) namely

l2 ð1 þ Vðx0 ; t0 ÞÞ

R^ ¼ 1 þ

1 þ ner I r ðx0 ; t0 Þ

0

Vðx ; 0Þ þ

£

ð t0

!

0

0

0

0

0

V r ðx ; s Þds 2 Vðx ; t Þ ;

0

2 1þ

l2 Vðx0 ; t0 Þ

1 þ ner I r ðx0 ; t0 Þ

"

!#

ð t0

1

0 0

0 0

0

Cðx ; t Þ þ m Cðx ; s Þ ds

£

;

n

0

›V

l2 V

þ V r ðx0 ; t0 Þ;

¼ 2k 4 R

1 þ nre I r ðx0 ; t0 Þ

›t 0

›I r

¼ I sr ðtÞ 2 mir I r :

›t 0

ð6:12Þ

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

The source term isr has been replaced by its non

dimensional form I sr ðt0 Þ ; T isr ðtÞ=r 0 ; ir by I r ¼ ir =r 0 ;

nre ¼ r0 nre and mir ¼ T mir as before.

Thus the dynamics of inhibition of growth factor

(Eq. (6.8)) or the inhibition of receptor activation

(Eq. (6.12)) have precisely the same form. This model

predicts that equal inhibitor equilibrium constants and

equal bolus concentrations or source rates of either type of

inhibitor will result in equal inhibition of fibronectin decay

and aggregation of endothelial cells.

Remark 3 If one introduces both inhibitor types the

resultant equations are modified to the extent that l2 in

Eq. (4.5) is replaced by

ð1 þ

l2

r

0

0

ne I r ðx ; t ÞÞð1

þ nev I v ðx0 ; t0 ÞÞ

wherever it appears. Therefore, even if the equilibria for

both types of inhibition are relatively modest, i.e. the

constants nve ; ner are not inordinately large, the combined

effect of two such inhibitors is greater by a factor of one of

them over the other than either one alone (This result is not

unexpected. It is dictated by the kinetics. If both V and R

are inhibited, then the concentration of ½V A RA is very

nearly proportional to the product of the concentrations

of each active species by our version of the Michaelis–

Menten hypothesis).

When Eq. (6.3) is the mechanism, the situation is much

easier to describe: First, the concentration of protease is

replaced by the concentration of active protease in the

fibronectin and EC movement equations. Then

½C ¼ ½C A þ ½C I þ ½C A F

¼ ½C A þ ½C I þ ½C A ½F=K m ;

ð6:13Þ

167

the first seven equations in (4.5) are unchanged while

the last two and the cell movement equation become:

›I c

¼ 2mic I c þ I sc ðt0 Þ;

›t 0

›F

4

¼ Fð1 2 FÞN 2 K cat l3 C a F;

›t0 T f

ð6:16Þ

›N

›

›

N

¼ D 0 N 0 ln :

›x

›x

›t 0

TðCa ; FÞ

A final observation: it is straightforward to modify

either Eq. (4.2) or (4.5) in the case that one has one or

more inhibitors, one which acts against growth factor, a

second which acts against receptor signaling, and a third

which acts against protease.

THE NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS

Below we present some simulations using an initial bolus

of growth factor rather than a source. We take

v0 ðxÞ

¼

8

d

< V 0 N½12cosð2pðx2xl Þ=ðxr 2xl ÞÞ if xl #x#xr

:0

if 0#x,xl or xr ,x#L

ð7:1Þ

where N ¼NðdÞ is a normalizing constant chosen so that

ð xr

v0 ðxÞdx ¼V 0 :

xl

½CI ¼ nce ½I c ½C A :

The total concentration of enzyme available for

protease degradation is ½C 2 ½CI :

We see that

½C A ¼

1þ

½C

þ ½F=K m

nce ½I c ð6:14Þ

which must be small in order to inhibit the onset of

angiogenesis. This will be the case if nce is very large and

n is not too large in the case that the inhibitor

concentration is modest. Unfortunately, n is large, and

for at least one inhibitor, plasminogen derived angiostatin

which is an inhibitor of tPA, the equilibrium constant is of

the order of one (mM)21 and hence is not very large.

Suppressing ðx0 ; t0 Þ and passing to dimensionless

variables,

C ¼ C a þ Ci þ rf Ca F;

ð6:15Þ

C i ¼ nec C a I c ; C a ; C 2 Ci :

This choice, for large d corresponds roughly to a

d-function bolus of magnitude V0. Since the amplification

factor n is not known (and is also growth factor dependent)

we have taken it to be a constant, for lack of better

information at the current writing.

We used the values in Table IV for the various

parameters and constants: in the above table, the constants

K 1m ; K 1cat are taken from Heaton and Gelehrter (1977). The

constants k5, t0 are based on the estimated EC response

time to growth factor (Unemori et al., 1992). The choices

2

cðFÞ ¼ 4Fð1 2 FÞ and fðcÞ ¼ Ace 2jc were taken in the

probability transition function. (Here A is the reciprocal of

2

the maximum value of ce 2jc ).

In the actual simulations below we have reduced the

constant S0 by a factor of 105 in order to illustrate how the

growth factor draws on the external resources via this

transfer mechanism.

(1) In the first set of simulations, illustrated by the eight

panels in Figs. 2 and 3, we fix the initial concentration of growth factor. There are two input sources

168

H.A. LEVINE et al.

TABLE IV Parameter values

References

K m ¼ 0:7813 mM

K 1m ¼ 2:93ð1023 ÞmM

K 2m ¼ 1:4286ð102 ÞmM

k ¼ 0:6667ð1021 Þh21

r0 ¼ 1:0 mM

p0 ¼ 1:0 mM

mr ¼ 0:01 £ m

mc ¼ 0:01 £ m

nre ¼ 5:0ð106 ÞmM

nce ¼ 5:0ð106 ÞmM

iv ðx; 0Þ ¼ 5:0ð1024 ÞmM

ic ðx; 0Þ ¼ 5:0ð1024 ÞmM

isr ðx; tÞ ¼ 0:0

isc ðx; tÞ ¼ 0:0

T ¼ 1:0 h

D ¼ 3:6ð1025 Þmm2 h21

xl ¼ 0:0

f M ¼ 1:0ð1022 ÞmM

a1 ¼ 1:0ð1023 Þ

g1 ¼ 1:2

n ¼ 2ð103 Þ

V 0 ¼ 2:5ð1024 ÞmM

K cat ¼ 1:484ð10Þh21

k2 ¼ K 1cat ¼ 9:42ð1028 Þh21

k4 ¼ 1:04286ð104 Þh21

t0 ¼ 1:5ð10Þh

s0 ¼ 2:442ð103 ÞmM

m ¼ 4:56 h21

mv ¼ 0:01 £ m

nve ¼ 5:0ð106 ÞmM

ir ðx; 0Þ ¼ 5:0ð1024 ÞmM

Fields et al. (1990)

Heaton and Gelehrter (1977)

Kendall et al. (1999)

See footnotes

Terman et al. (1992); Waltenberger et al. (1994) for r0, Engelen et al. (2000) for s0

Assumed that p0 < r0 : Boffa et al. (1998) for m

Simulated value

Simulated value

Simulated value

Simulated value

Simulated value

Simulated value

isv ðx; tÞ ¼ 0:0

T f ¼ 1:8ð10Þh

L ¼ 100m ¼ 0:1 cm

xr ¼ 100m

b1 ¼ 1:0ð1023 Þ

g2 ¼ 1:2

d ¼ 30

Time scale. Orme and Chaplain (1996); Yamada and Olden (1978) for Tf

Sherrat and Murray (1990) for D. Length scale

Terranova et al. (1985) for fM. See foonotes for CM

Simulated value

Simulated value

Simulated value

Simulated value

which regulate the EC-fibronectin response. The first

is the quantity of growth factor in the bolus while

the second is the quantity of externally supplied

resources reflected in the magnitude of S0. This is

quite a large quantity, and for the levels of growth

factor which are found in tissue samples, is far more

than is needed to drive the computations. Therefore,

in the figures below, we have reduced the number

S0 by a factor of 105. The second regulator of EC

response is the magnitude of the growth factor bolus.

The computations illustrate the instability discussed above. As one can see from the figures,

although the growth factor decays very rapidly due to

the large influx of extracellular resources, its effects

FIGURE 2 Extra- and intracellular resource, receptor and activated receptor time courses without inhibitor.

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

169

FIGURE 3 Growth factor, protease, fibronectin and endothelial cell time courses without inhibitors.

FIGURE 4 Extra- and intracellular resources, receptor and activated receptor time courses with growth factor or receptor inhibitor ðtv ¼ 0:0Þ:

170

H.A. LEVINE et al.

FIGURE 5 Growth factor, protease, fibronectin and endothelial cell time courses with growth factor or receptor inhibitor ðtv ¼ 0:0Þ:

FIGURE 6 Extra- and intracellular resources, receptor and activated receptor time courses with growth factor or receptor inhibitor ðtv ¼ 50:0Þ:

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

FIGURE 7 Growth factor, protease, fibronectin and endothelial cell time courses with growth factor or receptor inhibitor ðtv ¼ 50:0Þ:

FIGURE 8 Extra- and intracellular resources, receptor and activated receptor time courses with protease inhibitor ðtc ¼ 50:0Þ:

171

172

H.A. LEVINE et al.

are felt after several hours in the form of a protease

“bolus”. This bolus rapidly disappears although the

fibronectin and EC profiles “remember” it. Notice

that the EC concentrations in panel 8 clearly follow

the fibronectin concentrations after 100 h (when the

protease has nearly all decayed) as the theory dictates.

Observe also that the fibronectin density vanishes

over an interval of approximately 6– 8 microns, about

the diameter of a capillary. This opening is “lined”

with EC in the sense that the EC density is highest

along the edges of the capillary opening and vanishes

near the center of the capillary opening.

(2) With the above bolus of growth factor, a uniform

bolus of growth factor inhibitor (or, as remarked

above, receptor inhibitor) of concentration of

5:0ð1024 ÞmM is introduced in the blood stream. The

results are illustrated in the second set of eight panels.

It is assumed that this inhibitor is very effective ðne <

106 mMÞ and that it has a long half life (We have taken

this to be 100 times longer than that of the protease).

In Figs. 4 and 5, the inhibitor bolus was introduced at

the same time as the growth factor bolus was

introduced. Notice that although the channel opening

does not close, it does become more sharply defined.

It is also narrower than had the inhibitor not been

introduced.

The effect of the inhibitor is to delay action of the

growth factor. As the inhibitor decays, the equilibrium

between the inhibited and uninhibited forms of the

receptor (or growth factor) shifts to the left releasing

more of the uninhibited receptor or growth factor.

If the decay constant for inhibitor is set to zero, then

the system shifts to a new state in which l2 is replaced

by l2 =ð1 þ ne I 0 Þ where ne is one of the two

equilibrium constants and I0 is the magnitude of the

inhibitor bolus.

In Figs. 6 and 7, the inhibitor bolus was introduced

50 h after the growth factor bolus was introduced.

Notice that while the protease density is reduced

considerably, the channel does not close at those

points where it was completely open (i.e. where

Fðx; tÞ ¼ 0). Notice the attempt by the endothelial cell

density to spread out at and slightly after 50 h. The

channel opening does not (and, in this model, cannot)

narrow in this case.

If we had included a diffusion term in the

fibronectin equation, then the channel opening

would close, although, since the diffusion constant

for fibronectin is very small, this would not be

noticeable here (Levine and Sleeman, 1997).

(3) Finally, a protease inhibitor is introduced in lieu of the

other two inhibitor types. Here again, it is assumed

that this inhibitor is long lived and very effective. The

inhibitor bolus was introduced fifty hours after the

growth factor bolus. (Introducing the growth factor

bolus at time zero just means that we will have

FIGURE 9 Growth factor, protease, fibronectin and endothelial cell time courses with protease inhibitor ðtc ¼ 50:0Þ:

A MATHEMATICAL MODEL

a decayed value of inhibitor at the time of onset of

protease production. This again involves a simple

rescaling of l2 at that time) (Figs. 8 and 9).

References

Boffa, M.B., Wang, W., Bajzar, L. and Nesheim, M.E. (1998) “Plasma

and recombinant thrombin-activable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) and

activated TAFI compared with respect to glycosylation, thrombin/

thrombomodulin-dependent activation, thermal stability, and enzymatic properties”, J. Biol. Chem., 2127–2135.

Bowersox, J.C. and Sorgente, N. (1982) “Chemotaxis of aortic

endothelial cells in response to fibronectin”, Cancer Res.,

2547–2551.

Davis, B. (1990) “Reinforced random walks”, Prob. Theory Related

Fields, 203 –229.

Eckhard, G. (1999) “Angiogenesis inhibitors as cancer therapy”, Hosp.

Prac., 63–84.

Engelen, M.P.K.J., Wouters, E.F.M., Deutz, N.E.P., Menheere, P.P.C.A.

and Schols, A.M.W.J. (2000) “Factors contributing to alterations in

skeletal muscle and plasma amino acid profiles in patients with

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”, Am. J. Clin. Nutr.,

1480–1487.

Fields, G., Netzewl-Arnett, S.J., Windsor, L.J., Engler, J.A.,

Berkedal-Hansen, H. and van Wart, H.E. (1990) “Proteolytic

activities of human fibroblast collagenaise; hydrolysis of a broad

range of substrates at a single active site”, Biochemistry, 6600–6677.

Folkman, J. (1992) “Angiogenesis-Retrospect and outlook”, In: Steiner,

R., Weisz, P.B. and Langer, R., eds, Angiogenesis: Key PrinciplesScience-Technology-Medicine (Birkhäuser, Basel).

Han, Z.C. and Liu, Y. (1999) “Angiogenesis: state of the art”, Int.

J. Hematol., 68–82.

Heaton, J.H. and Gelehrter, T.D. (1977) “Derepression of amino acid

transport by amino acid starvation in rat hepatoma cells”, J. Biol.

Chem., 2900–2907.

Kendall, R.L., Rutledge, R.Z., Mao, X., Tebben, A.J., Hungate, R.W.

and Thomas, K.A. (1999) “Vascular endothelial growth factor

receptor KDR tyrosine kinase activity is increased by autophosporilazion of two activation loop tyrosine residues”, J. Biol. Chem.,

6453–6460.

Kyriakis, J.M. and Avruch, J. (2001) “Mammalian mitogen-activated

protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and

inflammation”, Physiol. Rev., 807–869.

Lev Bar-Or, R., Maya, R., Segel, L.A., Alon, U., Levine, A.J. and

Oren, M. (2000) “Generation of oscillations by the p53-Mdm2

feedback loop: a theoretical and experimental study”, Proc. Natl

Acad. Sci., 11250–11255.

Levchenko, A., Bruck, J. and Sternberg, P.W. (2000) “Scaffold proteins

may biphasically affect the levels of mitogen-activated protein kinase

signalling and reduce its threshold properties”, Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.

97, 5818–5823.

Levine, H.A. and Sleeman, B.D. (1997) “A system of reaction diffusion

equations arising in the theory of reinforced random walks”, SIAM

J. Appl. Math., 683–730.

Levine, H.A., Sleeman, B.D. and Nilsen-Hamilton, M. (2000)

“A mathematical model for the roles of pericytes and macrophages

in the model for the roles of pericytes and macrophages in the onset of

angiogenesis: I. The role of protease inhibitors in preventing

angiogenesis”, Math. Biosci., 77–115.

Levine, H.A., Pamuk, S., Sleeman, B.D. and Nilsen-Hamilton, M.

(2001a) “Mathematical modelling of capillary formation and

development in tumor angiogenesis: penetration into the stroma”,

Bull. Math. Biol., 801–863.

Levine, H.A., Sleeman, B.D. and Nilsen-Hamilton, M. (2001b)

“Mathematical modelling of the onset of capillary formation

initiating angiogenesis”, J. Math. Biol., 195–238.

Orme, M.E. and Chaplain, M.A.J. (1996) “A mathematical model of

the first steps of tumour-related angiogenesis: capillary sprout

formation and secondary branching”, IMA J. Math. Appl. Med. Biol.,

73– 98.

Othmer, H.G. and Stevens, A. (1997) “Aggregation, blow up and

collapse: the abc’s of taxis and reinforced random walks”, SIAM

J. Appl. Math., 1044– 1081.

Paweletz, N. and Knierim, M. (1989) “Tumor related angiogenesis”, Crit.

Rev. Oncol. Hematol., 197–242.

173

Rakusan, K. (1995) “Coronary angiogenesis, from morphology to

molecular biology and back”, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., 257 –266.

Rous, P. and Jones, F.S. (1916) “A method for obtaining a suspensions of