Document 11163452

advertisement

is

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/shortrundemandfoOOangr

Dewey

HB31

.M415

working paper

department

of economics

SHORT-RUN DEMAND FOR PALESTINIAN LABOR

Joshua D. Angrisf

95-16

April 1995

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass. 02139

SHORT-RUN DEMAND FOR PALESTINIAN LABOR

Joshua

D. Angrist

95-16

April 1995

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

:

AUG 16

1995

LIBRARIES

95-16

SHORT-RUN DEMAND FOR PALESTINIAN LABOR*

by

Joshua D. Angrist

Revised: April 1995

Abstract

Palestinian residents of the

Israel.

Wages

West Bank and Gaza

Strip

have the option of working

who

paid to residents of the territories

are employed in Israel are

generally higher than wages paid in the territories, but the Israel

highly volatile.

wage

Beginning

differentials

in late

by work

in

wage premium

1987 with the Palestinian uprising, changes

is

in

location roughly parallel the pattern of Palestinian

absences from work in Israel. This paper discusses aspects of the demand for

Palestinian labor and explores the possibility that recent changes in relative

work

location are explained

A

workers.

model of the labor markets

estimate elasticities of

changes

in policies

This paper

by movements along an

demand and

in the

to evaluate the possible

governing Palestinian access to the

supported by the Falk Institute through a grant from the

Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. Preliminary

from the Ford Foundation. Special thanks

at the Israel Central

Ron

program

in

Bank of

Israel

The author bears

is

used to

economic impact of

human

market.

resources and has been

Manpower Planning Authority

work and data

collection

Hanoch, seminar participants

at

Hebrew

in the Israeli

was supported by

Zvi Eisenbach, Zeev Krischer, and other

Bureau of Statistics for providing the Territories micro

Eisenstadt, Giora

Strip

Israeli labor

Arbeli, and Natalie Aflalo provided expert research assistance.

Maggie

the

to

demand curve for migrant

West Bank and Gaza

part of the Falk Institute research

is

Israeli

wages by

data.

Thanks

also

staff

a grant

members

Samer Haj Yehia,

go

to Eli

Berman,

University, Tel Aviv University,

and Princeton University, and to the referees and editor for helpful comments.

sole responsibility for the content of this paper.

INTRODUCTION

I.

Since October 1970, changes

in access to the Israeli labor

changes and policy innovations

An

territories.

in

the

important recent example

market have constituted the major

economic relationship between

is

restrict mobility

Gulf War, the

the enforcement of laws against employing Palestinian workers

Service. Registration for

Post, 1988, Jerusalem

Recent changes

employment has

also

who

in Palestinian

in Israel in the

Israel

1

I

also

become more

the

up

Jerusalem

difficult (The

wage premium paid

new

Israeli stabilization,

high, reaching

crisis that

(see, e.g.,

Kleiman

wage

distribution

— 1990. One

of the most

document a number of significant changes

the virtual elimination of the

Following

climbed to a

On

are not registered with the Israeli

employment patterns have been widely noted

mid-1980s, a period of inflation and economic

in construction.

territories.

Israeli authorities stepped

of workers from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip over the period 1981

is

hand, strikes and

Media and Communications Center, 1991).

1992). In Angrist (1992),

important changes

On one

and employment opportunities for workers from the

other, beginning in 1988, and especially since the 1991

Employment

and the occupied

Israel

the Palestinian uprising, which has periodically restricted

access to the Israeli labor market because of actions taken on both sides.

curfews

field for

in the

to Palestinians for

working

included a severe contraction

however, the daily wage premium paid for work

in

40 percent by 1989.

Since December 1987, changes in the Israel wage premium have roughly paralleled the pattern

of absences from work by Palestinians employed

wage

increases

may

reflect

movements along a short-run

sudden withdrawal of labor from the

market that

An

is

in Israel.

territories.

Such a correlation suggests

Israeli

is

Israeli

taxes

on

is

demand

essential for developing effective policies

relationship between the Palestinian and Israeli labor markets.

Palestinian Authority

in

response to the

This paper develops a model of the Palestinian labor

used to estimate parameters affecting short-run

understanding of this issue

demand curve

that recent

for Palestinian labor.

governing the evolving

Suppose, for example, that the

able to tax the wages of Palestinians employed in Israel or to impose payroll

their employers.

How much

Palestinian Authority rationally choose to restrict exported labor supply so as to

earnings or tax revenue?

Might the

revenue are such taxes likely to generate?

Of more immediate

relevance, to what extent

maximize

repatriated

do higher wages

offset the

earnings costs of periodic restrictions on Palestinian labor mobility? Answers to such questions turn

1

Wage

differentials

between Palestinians working

declined throughout most of the 1970s (Zakai, 1988).

in Israel

and Palestinians employed locally generally

partly

on the

The paper

Palestinian

of demand for labor services exported by Palestinians to

elasticity

is

organized as follows.

employment

Israel.

II

provides background information on the Israeli-

relationship, describes data

from the Territories Labor Force Survey (TLFS)

Section

and provides a brief empirical description of Palestinian labor market outcomes

Section

outlines a simple equilibrium

III

interact to determine Palestinian

summary and some

that describes

how

wages and employment.

parameters in the model and Section

offers a

model

V

in recent years.

supply and demand for labor might

Section

IV presents

estimates of key

discusses policy implications of the estimates. Section VI

conclusions.

BACKGROUND, DATA, AND DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

II.

employment policy requires workers from the

Official Israeli

through the

(Israel

Israeli

Employment

employ

Employment Service

Service, 1991).

territories to

apply for work

in Israel

(ES), which then channels workers to Israeli employers

The ES

is

the only legal avenue through which Israelis

may

Palestinians, and the Palestinian payrolls of Israeli employers' are supposed to be disbursed

by the ES. The ES

also deducts taxes, social insurance contributions, and union dues

payrolls. Until recently, the

ES was

also the only legal

from these

employment agency for most non-college

educated Israeli citizens, and most job openings in Israel were posted through this agency (Berman

1994).

Legal restrictions notwithstanding,

employed

until the

1991 Gulf War, the vast majority of Palestinians

employers through the ES. Rather, most Palestinians

in Israel did not actually reach their

were contacted

directly

typically record

between 30 and 40 thousand registered Palestinians working for

in the 1980s,

The

Territories

This study

2

the

is

Israeli

employers or through a Palestinian labor contractor.

while data from the Israel Central Bureau of

CBS, 1991) show that

1.

by

Statistics'

Israeli

(e.g.,

100-1 10 thousand Palestinians were employed in Israel, including Jerusalem.

2

Labor Force Survey

based on

until

data

employers

(CBS) quarterly TLFS

TLFS

micro data. 3

TLFS

interviews are conducted

by

local Palestinian

Since early 1991, enforcement of the official work registration requirements has become

Gulf War

ES

March 1993, roughly 70,000

Palestinians

were registered as working for

stricter.

Israeli

From

employers

each month.

'Wage and employment data from the TLFS

are

compared

administrative records in the appendix to Angrist (1994).

to

wage and employment

data from

ES

3

enumerators employed by the

Israeli Civil

frame includes most households

status or

work

in the

Administration in the territories.

West Bank and Gaza

location of the head of household.

contains observations on

men aged

The TLFS

extract used to prepare this paper

18-64, interviewed in the years 1981-91

CBS,

Table

provides descriptive

1

Some 8-10 thousand

statistics for

the sample of

interviews were conducted each year in the

number of completed interviews

especially in the

Gaza

in the

fell

where the uprising

Strip,

The average age of men

in the

sample

is

Gaza

in

Gaza

attributable to the large

started earliest

number of new

force participation, which

at

Employment

shows

is

any given year. The sample sizes

and was most intense.

West Bank. Married men

men

are probably

are often completed

last

The

to 8.6 years in the

descriptive statistics also

that the fraction of the Palestinian labor force

Members of the

column of Table

rates are based

The

1

labor force

by proxy

West bank. This

is

partly

entered the labor force in the 1980s

show

a substantial increase in labor

men aged

18-24.

who were

in the text,

employed as wage-earners was

stable

not employed as wage-earners are either

data analyzed below are for wage-earners only.

show

that

41-50 percent of Gazans were employed

in either Israel

or Jerusalem.

4

in Israel

and

The proportion

on weighted counts from the TLFS. In 1991, there were an estimated 166,000 West

Bank and 102,000 Gazan men aged 18-64 working

working abroad

who

college graduates

35-41 percent of West Bank residents were employed

mentioned

the sample rotation

primarily a consequence of increased participation by

self-employed or unemployed.

These

between 22 and 30

patterns

roughly one-half.

The

Strip and

33 and the proportion married rose from 67 to 75

from 7.7 years

Strip and

(Angrist, 1992; Simon, 1988).

1

region of residence.

The average level of schooling rose considerably over the sample period, from 7.6 years

to 8.8 years in the

Table

are very low (6-9

with the onset of the Palestinian uprising in 1988,

over-represented in the sample because the interviews of employed

2.

constitute the bulk

women

West Bank. Because of

percent in the Gaza Strip and from 64 to 67 percent in the

respondents.

Men

men aged 18-64 by

scheme, only one-quarter of these observations are independent

that the

.

1991).

thousand interviews were conducted each year

show

of the employment

Strip, regardless

of the Palestinian labor force because labor force participation rates for

percent in the sample period;

The TLFS sampling

a few

men

in the reference

as

wage

laborers.

In addition to the

work

locations

are employed in Jewish settlements in the territories and a few were probably

week.

Work

abroad was an important source of employment for residents of

4

was

of the Gaza labor force working

in Israel

from 48 percent

The proportion of

to 41 percent.

stable until 1987; after 1987 this proportion declined

West Bank labor force employed

the

in Israel

increased from 22 to 27 percent between 1981 and 1987, and reached 29 percent by 1991. Between

1987 and 1991 the proportion of the West Bank labor force employed

in

Jerusalem declined from 13

10 percent.

to

Palestinian workers, especially those

of industries.

this

employed

In 1981, half of the Palestinians

in Israel,

employed

in Israel

worked

Palestinians

working

of the Palestinians

in Israel,

in construction;

number

by 1991

was the second most important source of employment

who were employed

in

in their region

of residence worked in the agricultural sector.

manufacturing, mining, other types of industries, and the service

sector has declined as the proportion

employed

in construction

construction and industry account for a larger share of local

Gaza

Strip.

has risen.

employment

Workers employed

in

West Bank than

in

in the

3

This study focuses on recent changes in Palestinian employment patterns.

days worked per month in Table

Gaza

for

accounting for 13-17 percent of total employment. Roughly 20 percent

The importance of employment

the

in a

proportion had risen to 70 percent. Most Palestinians working in Jerusalem were also employed

in the construction sector. Agriculture

the

have been concentrated

Strip and

from 23

Palestinian uprising.

An

difficulties in getting to

1

show

on average

West bank, again a consequence of

important component of this change comes from

1

data

a sharp drop in 1988, from 22 to 17 days for residents of

to 18 days for residents of the

work. Figure

The

the

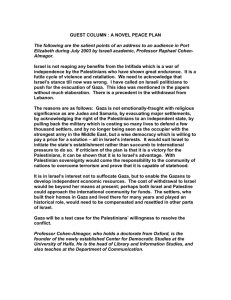

work absences and

shows the fraction of the labor force absent from work by

work-place location. 6 Data on absences exhibit a seasonal pattern across quarters and a large increase

in

absences beginning in 1988 and during the Gulf

A

related aspect of the changing

War

work environment

which plots the difference between daily hours worked

some of

'Statistics in this

Palestinians

in Israel

is

documented

in

Figure 2,

and locally by region of residence.

in Israel

worked

the sample period (Gabriel and Sabatello, 1986).

paragraph are from Angrist (1994).

employed

for migrants

of 1991.

West Bank who were employed

Until 1988, both Gazans and residents of the

the territories over

in the first quarter

in Israel see

For other analyses of the occupational mix of

Kleiman (1992) and Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein (1987).

"Absentees are defined as labor-force participants

or actively seek work during the reference

week but

job from which they were absent for any reason.

who

did not work, assist on a farm or family business,

reported that they had a job or farm or other agricultural

5

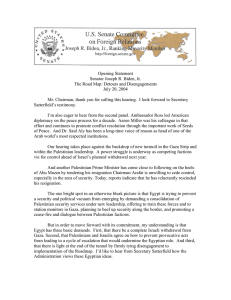

roughly one hour longer per day than men employed locally. Beginning

of workday grows to almost 4.5 hours for Gazans and almost 2.5 hours for residents of the

in length

West Bank.

It

seems

many proxy responses

likely that the

home and

record the time elapsed between leaving

to the

TLFS

question on hours worked

returning. Significant changes in hours

larger for residents of the

Gaza

Strip because

worked

on the job. 7 The gap has

are therefore most likely due to changes in travel time rather than hours

grown

1988, however, the gap

in

time-consuming security measures

at the

Gaza

border are relatively easy to enforce.

3.

Wages and work

location

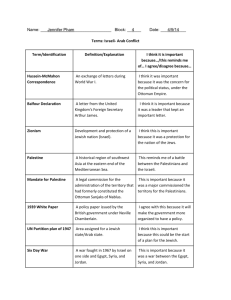

Figure 3 plots survey data on average real daily wages by work location for the period 1981-91 The

.

TLFS wage

series

Gaza

Israel, the

was computed from the monthly wages of men employed

West Bank, who reported

Strip, or the

real

monthly wages under NIS 10,000

quarter 1991 shekels). Daily wages were computed by dividing monthly

Figure 3 shows a decline in real wages

wage growth

to

grow

until early 1987.

1988 and the

into

Subsequentiy, real wages

flat

for the period

in early 1988.

The

real

fall

real

work

locations in 1984-85, with subsequent strong real

wages of men employed

men employed

fell thereafter; real

that the period

of the

territories

Jerusalem continued

in Israel continued to

at these locations.

wages

in

in the

grow

into 1989.

Real wages in Gaza were

West Bank

fall

1985-1989 was generally one of strong

Israeli citizens as well as for residents

(in 4th

wages by days worked.

wages of Palestinian men employed

sharply for

1987-89 and

Note

at all

in either Jerusalem,

sharply beginning

real

wage growth

for

(CBS, 1992).

Regression estimates are used to describe changes in average Palestinian wages conditional on

demographic

characteristics.

(computed by weighted

log(wJ

(1)

where 8^

and

/3 CT

and 7 P

7

last

is

is

is

=

Table 2 reports parameter estimates from the following equation

least squares using the

5„

+ £c sy^ + L t

a quarter effect in year

an age effect

in year

t,

t,

b^

a schooling effect in year

t,

a^

bi.7*

is

a

CBS

sampling weights):

+ ft +

dummy

E.

c^

+ J^ +

variable that indicates if

a

dummy

variable indicating

ck a

dummy

variable indicating if

is

The TLFS question on hours worked asks "How many hours did

week?" To estimate hours worked per day,

I

va ,

multiplied this

divided by the number of reported workdays in the month.

if

i

i

i

is in

is

is

in

age group c

schooling group g

employed

in industrial

member work

at all

jobs

number by 4.35 weeks per month, and

then

the household

6

sector

and

s

in Israel in

works

in

0,

is

Jerusalem and

^

(1)

falls

of 36 percent

until

an industry wage effect

year and

Column

premium

fi^ is

is

f

;

a

is

a work-in-Jerusalem effect.

is

dummy

t, J

is

:

a

variable indicating

dummy

from 17 Qog) percent

Columns

in 1991.

less than

in

if

i

in Israel.

The

The wage gap

in favor

of

which decline monotonically

men who completed 13-15

Elsewhere (Angrist 1992)

I

years of

discuss the

workers were a major contributing factor

in the

Angrist (1992) also shows that different types of workers were

in Israel at different times,

may

works

1981 to zero in 1984 and 1985, then rises to an all-time high

6 percent for the period 1987-91.

decline in returns to schooling.

schooling coefficients)

i

8

(2)-(3) report schooling coefficients,

slightly.

if

variable indicating

of Table 2 reports estimates of the daily wage premium for working

possibility that shifts in the supply of educated

employed

t,

a work-in-Israel effect in year

1989 and then increase

schooling

in year

reflect

which suggests

that changes in the Israel

wage premium (and

worker heterogeneity. But estimates using panel data show

that

these changes are apparent even after allowing for individual heterogeneity.

The

industry

agricultural

workers

wage

workers earned

in agriculture

community

effects in

columns (4)-(7) indicate that

least

percent by 1988.

30 percent

stable, at

to 15 percent.

Palestinians have the

The

would seem

in Israel

8

are:

in construction

to reflect

relationship between wages

OLS

are:

The omitted

20

and agricultural wages, relative to wages

in labor

markets where

in Israel.

Palestinians

employed

men employed

in Israel, for the years

1987-1991.

25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64. The schooling groups indexed by g

13-15 years, 16 or more years. The industries indexed by

construction, and services.

— to

construction has been fairly

estimates from a simple regression of wages earned by

c

grew

and days worked

on the average days worked by

The age groups indexed by

and almost as much as

however, shrinks from roughly

upward pressure on wages

most employment opportunities

This subsection describes

agriculture,

The wage gap between manufacturing and

roughly 15 percent. The growth

1989, however,

paid to construction workers also

The wage gap between construction and

in the service sector,

4.

in the general service sector,

The premium

By

group (public and

less than those in the reference

more than those

those in the manufacturing sector.

beginning of the sample period

while construction workers earned most.

were no longer paid

services), earned

in the

industry group

is

s are: agriculture,

public and

community

manufacturing and related,

services.

7

Some of these

regressions also include controls for average daily wages of Israeli citizens in Israel

(derived from National Insurance Institute (Nil) data; see Angrist 1994.)

estimates do not have a structural

Palestinians

working

wage

Israeli

Israelis

Adding the average wage of

employed

Israel slightly,

to

in Israel,

estimates from a regression of wages

for the first

two quarters of 1991. Column

on the average daily wage of

Israelis

employed

on days

(2)

Israeli citizens to this basic

and the average wage of

in construction

reduces the coefficient on average days worked by Palestinians in

in agriculture

from -0.17

OLS

War dummies

reports the results of adding Nil data

equation.

days worked by Palestinians

trends.

(1) in the top half of Table 3 reports

worked, quarter dummies, and 2 Gulf

OLS

they document the fact that wages paid to

in Israel are negatively correlated with

even after controlling for

Column

interpretation,

Although these

-0.14.

Separate regression results by industry for

men employed

in agriculture, construction,

and

manufacturing also show a negative covariance between days worked and average daily wages, even

after controlling for

wages earned by

Israeli citizens (except for

example, the estimate of the coefficient on days worked

manufacturing workers).

For

in the construction section in a regression

of log average daily wages paid to construction workers on days of work

is

—0. 16. Note

that for

each industry group, wages paid to Palestinians working in Israel are strongly positively correlated

with the wages paid to Israeli citizens working in those industries.

movement

wages

in Palestinian

reflects

an

Israeli trend

This suggests that some of the

or demand shock, and highlights the

importance of isolating a source of exogenous variation in labor supply that can be used to identify

structural

III.

demand parameters.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This section develops a theoretical framework that can be used to interpret the impact of exogenous

supply shocks on Palestinian wages and employment. The days worked and daily wages of workers

from the

territories could

possibility of

Israel.

be affected by work opportunities

employment

in Israel should act to close the

in Israel in at least

two ways.

First, the

gap between wages paid locally and

in

This means an increase in wages paid to workers employed locally and a reduction in labor

costs for Israeli employers. Second, higher Israeli

and services produced

worked

to

in the territories.

slow the growth of an

A

wages may stimulate

comparative advantage

industrial base in the

local

demand

in labor services

West Bank and the Gaza

for products

may

also have

Strip (Metzer, 1992).

8

However, the analysis presented here takes the

industrial structure

of

Israel

and the

territories as

given.

The following model

assumed

territories are

describes key features of the Palestinian labor market.

to supply

9

Workers

in the

working days per month according to the following labor supply

equations:

N

(2)

where L

wm

tj(w,,

•

Zj);

,

a per capita supply function,

is

w,

j

=

j

= m,

is

the

I, for local

supply in the territories,

for migrants

wage paid

working

in Israel,

in the territories,

;

paid in Israel, z, and z m are variables that shift the per capita functions, and

working-age population

N

wm

is

is

the

wage

the size of the

in the territories.

Workers employed

locally

cases, the production function

is

produce y„

assumed

and workers employed

in Israel

to exhibit constant returns to scale,

produce y m In both

.

with the following unit

cost functions:

Cj(Wj, Xj);

(3)

where x

is

j

=

I,

m

the price of a second Hicks composite input in each production function.

}

Local demand for the local product, y„

and

in the territories,

N

(4)

where

E=

demand

v/JLm

is

local

assumed to be a function of the wages paid

good,

p,:

the per capita earnings of Palestinian workers, and d,()

component of "export demand" by

good without introducing substantive changes

good

is

in Israel

,

function. This function can include a

Palestinian

Israeli

a,(E, p,)

•

+

w,L,

and the price of the

is

in

=

d,(E, p,)

y»

=

«L(p

a per capita

Israel for the local

what follows. Aggregate demand

assumed to be a function of price, d D (p J. Equilibrium

y,

is

in the

for the

product market requires

(5)

9

This model

is

J

similar to a

,

model of the labor market for immigrants outlined by Altonji and Card ( 199

1

).

9

where

d,

= N

d,(E, p,).

•

Producers are assumed to be cost-minimizers in the factor market, so that conditional factor

demands can be obtained from

we

cost functions

by Shepherd's Lemma. In factor market equilibrium,

therefore have:

Vj

(6)

where

cjt (-)

where

t

}

Cj^Wj,

•

=

Xj )

£j(w„

wm

,

Zj);

j

=

i,

m

denotes the partial derivatives of the unit cost function with respect to wage rates, and

= N

•

Lj.

Finally, firms are

assumed

to

choose a level of output by equating marginal cost to price, where

each firm takes the product price as given. Therefore, product prices are set by

(7)

Pj

Equations

and

in Israel,

=

Cj(Wj, Xj);

(5), (6),

and

(7)

=

t,

m.

determine the equilibrium level of Palestinians' wages paid locally

and the prices of goods produced using Palestinian labor locally and

exogenous variables that

affect equilibrium are the prices of other inputs,

the labor supply functions,

The

j

effect

of

and z m

z,

shifts in

x,

and x m

in Israel.

,

and

The

shifts in

.

exogenous variables on equilibrium wage rates can be obtained by

substituting (7) into (5), and (5) into (6) to give

d,[E, c,(w„ x,)]

•

c„(w„

x,)

=

£,(w„

wm

,

z,)

(8)

d.[c.(w„ xj]

•

c nl (w n ,

xj =

t n (w„

w B zj

,

This substitution eliminates the endogenous product prices and leaves a pair of equations that jointly

determine the wage rates,

w, and

Taking logarithms and

satisfy the following

wm

.

differentiating, the proportional

two equations:

changes in wage rates can be shown

to

10

[{X,+i7 / ,-e„]d//iw, + [^Xin -€ < Jd/nw IB

= e h (l-^)d//i2,- CllB(l-^d//izB -ij <xd//ix

(9)

-

e a ,dlnw,

+

[ri

mm

- e^dlnw^

=

where e^

wm

k

,

=

at location

product,

and k

w,;

for

I

e^dlnza

the elasticity of labor supply to location

is

=

z for z m or

with respect to factor price

j

y„

<t>

=

dlnE/dlnw, and X^

w,£,/E

=

is

/

k.

j

i]

axdlnx m

£

is

,

with respect to argument k

Similarly,

z,).

10

-

the income elasticity of

demand

for

demand

the elasticity of factor

is

j/^

= m

(k

for the local

the share of local earnings in total labor earnings, and

X,

=

d//zE/d/nw m characterize the impact of wages on earnings."

Given estimates or assumptions about the underlying

structural parameters,

system

(9)

can be

used to predict the impact of exogenous demand shocks (components of dlnx,, dlnx J and supply

shocks (components of dlnz,, dlnzxj on Palestinian wages and employment.

provides a framework for estimation.

Note

that the terms in (9) can

This system also

be re-arranged and simplified

as follows:

d/nw,

= (I/tihWM, -

(£/i?„)d//iE

-

(r)jti„)dlnx„

(10)

At

this point, the definitions

any

of d/nx m and dlnx, are expanded to include labor demand shocks of

sort, as well as shifts in the prices

of other factor inputs.

12

dlnxm and dlnx, can therefore be

interpreted as error terms for the purposes of structural estimation.

Supply shocks

that are

uncorrected with these error terms (or transformations of the error terms) can be used as

instrumental variables to identify the parameters in (10).

10

and

This

is

the total elasticity of

elasticities

of factor substitution

"These parameters are X,

12

The

demand

role of

x,

and

(including scale effects), derived from the Hicks-Marshall formulas

(see, e.g.,

Hammermesh,

= #l+e«) + ^(l-tf)

x,,,

and \>

in the theoretical product

components are interpreted as a vectors of variables

1986).

=

(l-Ml+O

+

e, m<f>.

demand equations can be generalized so

that include prices

of other factor inputs and a generic

demand shock. The product demand equations then become:

y,

The only

=

d,[E, c,(w„ x,), x,]

;

ym

=

djcjw,,, xj>

implication of this change for equation (9)

is that

ij

(i

*J

and

•

tj

that these

to

must be redefined.

11

IV.

STRUCTURAL ESTIMATION

The supply shocks

to be used for instrumental variables (TV) estimation consist of a quarterly

time series data on person-days under curfew

Army

data appendix.

disturbances in the territories.

civil

The most prominent

Figure 4 also shows

days under curfew

combined with

feature of Figure

positively correlated with the

4

is

Both series are described

in the

the extended curfew during the Gulf War.

IDF

series

on

civil disturbances.

The curfew

are useful here because curfews and closures of the territories have a major impact on the

of Palestinians working

Israeli

with the exception of the Gulf War period, the Palestinian series on person-

that,

is

Strip,

Figure 4 plots the Palestinian curfew data along with the Israel

data on civil disturbances.

Defense Forces (IDF) data on

West Bank and Gaza

in the

in Israel.

It

data

number

should be noted, however, that curfews are often imposed in

response to disruptive incidents or personal attacks that can directly or indirectly shift local labor or

product demand as well as labor supply to

disturbance data

is

IDF

that the

Israel.

The value of having both

the curfew and

data on disturbances can provide a partial control for the local

disruptions associated with incidents leading to curfews.

1.

Measurement framework

DDF

In addition to using the

structure

in the

disturbances data as a control variable, a variance components

introduced to allow for the fact that supply shocks like curfews and closures can appear

is

demand equation or be

associated with variables that have an impact

denote a vector of candidate instruments that might

zm

and

in the notation

z,

demand shocks

in

period

t

shift labor

of the previous section).

The

on labor demand. Let

Z,

supply at either location (Z, includes

candidate instruments are connected to

as follows:

(11)

where tb and x, are population regression

uncorrected with

and v,

is

Z,

by construction. As an

restricted to

Assumption

1

coefficients and u mt

identifying assumption, the relationship between

be proportional:

ir a

=

kt,

for

and u„ are random components

some

constant, k.

ir m

12

In other words, the elements of Z, can be bundled in a linear combination that captures

demand shocks generated by

Assumption

in the

1

is

more than

requires

generate an estimating equation, the

linear, so that

when

/nw n

(12)

,

Note

that if Z,

itself is

the

a scalar,

not really a restriction. In practice, however, identification of structural parameters

demand equations

To

Z, up to a factor of proportionality.

all

=

equation (10)

K/nw,

demand

functions are assumed to be approximately log-

quasi-differenced across locations in period

is

+ (1/OfoC -

t

a single instrument.

(Khtdlntn

+

Oc$/ij„)/nE,

—

Quasi-differencing removes supply shocks other than (u^

error term in equation (12)

is

tcu tt)

therefore uncorrected with Z,,

+

(u m

t,

we

- kuJ

have:

.

from the demand equation. The

and elements of Z, are available as

instruments.

Finally, an estimating equation for individual observations

(12) holds for average log

wages

in period

possibility of composition effects as

for workers

workers move

level regressors, X*, is also included.

Israel

t

in

In particular,

is

derived by assuming that equation

employed

in Israel.

But to allow for the

and out of the labor force, a

I

set

assume the wages of worker

i

of individual-

employed

in

can be written:

//zw mt (i)

=

+

Inv/^

Xh/S

+

ut (\)

,

or

Inv/Ji)

(13)

=

ic//iw ft

+

where p (i)

t

is

+

{XlitJlntn

+

X,fi

{(Unt

-

-

Oc/ij„)/fif„

«i„)

+

pt (i)}

+ Wv^lnE,

,

an error term that has mean zero each year by construction (because

dummies). The individual-level regressors should help control for the

can affect the demographic mix

(e.g.,

of Palestinian workers coming to

To

illustrate

how

by favoring married and

skilled

fact that Israeli

Israel.

instrumental variables can be used in this model, suppose

of Table 3 and are reported in the bottom half of Table

of linear and quadratic terms

total

of 4 instruments.

in

curfew policies

workers) as well as the number

estimates using curfew data in such a specification correspond directly to the

in the top half

XH includes year

person-days under curfew

in the

3.

OLS

The

*=0

and 0=0. IV

estimates reported

instruments consist

West Bank and Gaza

Strip, for a

Estimates of the coefficient on days worked can be interpreted as estimates

13

of (l/'Jmm)

m th e restricted model.

The

are pooled, suggesting an aggregate

of

Israeli

rises.

The IV

citizens are

when

partial

in this

The over-

shifts.

improves

fit

data on the wages of Israeli citizens are added, but the test statistics consistently

how

is

also highly at odds with the data.

the curfew data can be used

worked by work

location.

when

A positive relationship

IV problem

relates

the relationship between

in the

is

given in Figures 5-7, which

is

k

is

set equal to

1

and

rf

ma =rj n

wages by work location

.

to the

Figure 5 plots the relationship between the Israel/West

difference and person-days under curfew in the

days worked

industries

all

These estimates

reported at the bottom of Table 3 indicate that the

In this case, (13) simplifies to an equation relating the difference in

quarter effects.

to -4.5.

demand

control for

present a graphical depiction of IV estimates of equation (13)

Bank wage

when

somewhat but remain negative when the average wages

added to the model as a

alternative illustration of

difference in days

to -.28

and wages go up when the number of person-days

fall

suggest that this highly restricted specification

An

from -.23

on the order of -3.5

elasticity

estimates decline

identification test statistics

considerably

demand

work days

are a consequence of the fact that

under curfew

resulting estimates range

West Bank,

after regression-adjusting for

The second reduced-form

apparent in the figure.

equation

days worked to the number of person-days under curfew. Figure 6 shows

West Bank curfews and the

West Bank

(after partialing

difference between days

out quarter effects).

The

worked

in Israel

and

slope of the line in Figure

6 suggests a clear negative relationship.

Finally, Figure 7 plots the

therefore a picture of the

of the line

approximately

demand

2.

IV estimate of a

in the figure is

days under curfew

in the

- 1.4.

two Y-axes

in

labor

Figures 5 and 6 against one another. Figure 7

demand curve

in this restricted

model.

The

is

slope

approximately —1.3. The slope of the same line computed using person

Gaza

Strip and using the

Gaza

Strip

is

as the comparison region

is

In the context of equation (13), these relationships imply that short-run Israeli

for Palestinian labor

is

not very elastic.

Parameter Estimates

When

estimating equation (13) without k restricted to be zero, a local region for quasi-

differencing has to be chosen to control for

demand shocks

correlated with the instruments.

Empirical results are reported here for comparisons to both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The

dependent variable

Men employed

in

is

the log of positive real daily wages for the sample of

men employed

in Israel.

Jerusalem are excluded from the analysis. The regressors include the quarterly

14

average log local wage in the comparison region (West Bank or Gaza Strip) by industrial sector

(agriculture, construction, or other), the quarterly average log days

worked

quarterly average log days

monthly wages (over

real

CBS

all

in the

worked

sectors) in the comparison region.

allows for an industry-specific constant.

13

This procedure

To compute

and IV estimates.

treated as endogenous: days

worked

comparison region, and average

in Israel,

total

sector, the

Averages were computed using the

men from

days worked

the

different industries but

equivalent to estimation of (13)

is

separately by sector, with the restriction that the parameters of interest are the

OLS

by

comparison region by sector, and the log of total per capita

sampling weight and excluding outliers. The estimation pools

Table 4 reports

in Israel

IV

in the

same across

industries.

estimates, four variables

comparison region, wages

earnings in the comparison region.

14

The

instruments include linear and quadratic terms in person-days under curfew in the

were

in the

four excluded

West Bank and

person-days under curfew in the Gaza Strip. Other regressors included in the equation and instrument

list are:

linear

and quadratic terms

quarter dummies,

number of

civil

disturbances in the comparison region, 3

4 year dummies, 2 Gulf-war quarter dummies, 2 industry dummies, and

individual-

and schooling dummies as

in equation

level regressors including

(1),

in the

dummies

for marital status, and age

without time-varying coefficients. The year dummies control for annual macroeconomic shocks

in Israel, as well as

changes related to the wave of immigrants that began to arrive in 1990, although

come

dramatic changes in the size of the labor force do not

If

no additional

restrictions are

until 1991.

imposed or instruments added, the parameters

are just-identified. Part of the identification therefore

comes from the fact that quadratic functions are

If there is

an omitted nonlinear term in one

To provide some

evidence on the validity of the

used as instruments while the regressors are log-linear.

of the regressors, identification breaks down.

in equation (13)

orthogonality restrictions, and to see whether the estimates are sensitive to alternative identifying

assumptions, additional restrictions were imposed one

13

In principle the

qualitatively similar.

14

model applies industry by industry but

Only pooled estimates are reported

Average earnings are not linked by an

latter variables calculated for

results

from models disaggregated by industry are

to save space.

identity to local

and

Israeli

wages and days worked because the

a work location while average earnings are calculated for a region of residence.

Average earnings by region includes counts of zero earners

are available for this sample.

at a time:

in the

denominator.

No data on non-wage income

15

income

Assumption 2a

(the

Assumption 2b

(demand

elasticities

proportionality);

Assumption 2c

(local

and

of local product demand

elasticity

Israeli

is

zero);

£

=

0.

and demand shocks are related by the same factor of

tj„

=

kt/^

.

demand shocks induced by

Given one or more of Assumptions 2a, 2b, or 2c, equation (13)

Z,

are the same);

k

=

1.

over-identified and subject to

is

partial validation using data.

Results using the

Gaza

Strip as a

comparison region appear

in the first

5 columns of Table 4

and results using the West Bank as a comparison region are reported in columns (6-10). The results

on the regressors

are reported as coefficients

comparison region

of

on log

Columns

(that the

(1-2) report

income

the coefficient

in the

earnings

elasticities (tj^,

OLS

elasticity

k,

worked

total per-capita

column, the implied

in each

OLS

an estimate of

the coefficient on days

l/rt mm ,

the coefficient

2a

is

equation (13).

in

is

on log days worked

an estimate of

,

K^/ti lt

is

in Israel is

in the

an estimate

an estimate of —k/i}„,

Below

.

on log wages

and

the estimates reported

£) are also reported."

and IV estimates for the Gaza Strip comparison under assumption

of agricultural product demand in the comparison region

zero.)

is

The

estimates are unlikely to have a structural interpretation, but they are reported for comparison

OLS

estimate of the Israeli

purposes.

In this case, the

estimate

negative, though imprecisely estimated.

Gaza

coefficient

comparison region

m and

ij

The

is

Strip as a

-2.2, with local

demand suggest

industries

models

Israeli

demand

elasticities

between -.76 and

Estimates of the income elasticity of product

income do not generate large changes

in

product demand for the

in

the data well.

columns

(1-2),

OLS

estimates of

1/tj,^

using the West Bank as a comparison region

(column 6) are positive while IV estimates (column 7) are negative.

columns (7-10) support the notion

out of four of the estimates of

that negative

\lr^ am

are in the

demand

wage premium

for married men.

The age

Most of the IV

elasticities explain

same range

wage

coefficients imply a

The marriage

results in

increases and

as those in columns (2-5).

"Coefficients on the individual-level regressors are not reported.

percent

IV

employing wage-earners. Finally, the chi-square goodness-of-fit statistics suggest that these

fit

As

elasticities in a similar range.

that declines in

elasticity is positive but the

Other IV estimates based on models using the

comparison region generate estimated

demand

demand

The

two

results

coefficients suggest a 5

concave earnings

profile.

16

in

column 9 corresponds most closely

to the graphical representation in figure 7.

But some

results

(such as those in column 10) clearly cannot be rationalized in the context of the model outlined here.

On

the other hand, estimates using the

West Bank

as a comparison region are associated with

larger values of the goodness-of-fit statistic than estimates using the

region.

the

Gaza

Strip as a

much

comparison

This suggests that the restriction motivating IV estimation are more likely to be satisfied for

Gaza

Strip

comparison used

in the

models underlying columns

(2-5).

16

V. Policy Analysis

Empirical results from the previous section can be combined with the theoretical framework from

Section

market.

III

to evaluate the possible impact of policies that reduce Palestinian access to the Israeli labor

To

illustrate the potential labor

who were regularly employed

or unable to

come

to

work

at current

half the workers

in Israel (including

wage

enforcement of access rules, the sale of

Suppose also that

shifts,

I

use the general comparative

and a simple numerical example. Suppose that half of the roughly 105,000

statics relationship, (9),

Palestinians

market impact of supply

rates.

Israeli

Jerusalem) before 1991 were unwilling

This shift might be the consequence of

work permits

stricter

to workers or employers, or both.

local (in the territories') labor supply shifts to partly offset this reduction, so almost

who used

means about 26,000 new

to

work

in Israel are willing to

local workers, implying

work

locally at current

an increase of a

little

wage

rates.

This

over 15 percent in local labor

supply.

The

possible consequences of such a scenario are described in Figure 8, which shows a range

of solutions to equation (9) when

e

mdlnz m =

-0.50 and

assuming an income

demand

is

elasticity

elasticity

assumed to be -1.

of demand of

1

The upper

for the local product; the lower part

was

calculated

These parameter choices are

"The notion

that

Gaza

is

that feeds

solutions are

calculated

of demand equal to 0. In both halves, the local

demand

The

was

Table 4 because the table shows no evidence of a highly

price-elastic local product

+0.15.

part of the figure

presented in terms of the impact on labor earnings.

assuming an income

=

e u dlnz,

in the

elasticity

of labor

range of estimates reported in

elastic local

demand

for labor or a highly

back into local labor demand.

a better comparison region

is

supported by Razin and Sadka (1993, p. 86),

who

note that, "... the Intifada (in Gaza) disturbed mostly the work of Gaza's residents in Israel." They also note

that non-agricultural sectors in

by industry

fit

the data

Gaza economy were hardest

on Gazan

agricultural well.

hit

during the uprising. Estimates of equation (13)

17

Four

lines are

about supply

graphed

elasticities.

labor in Table 4

is

17

in

each half of figure 8, corresponding to four different assumptions

The median

between -1.1 and

estimate of the elasticity of Israeli

Figure 8 suggests that for

-2.2.

demand

is

reduce

earnings by

total Palestinian

sufficiently inelastic, total earnings

elastic

more than 20

may even

demand) seems unlikely, both the

wage responses have worked

to

dampen

percent. If Israeli

Although the

rise.

50

elasticities in this range, a

percent negative shift in labor supply to Israel, offset by a 15 percent positive local

to

for Palestinian

demand

shift, is unlikely

for Palestinian labor

latter possibility (less

than unit-

theoretical and empirical analysis suggest that past Israeli

the aggregate earnings impact of reduced access to the Israeli

labor market considerably.

Finally, note that unless local product

demand

for

elasticities

much

demand

is

highly income elastic, these conclusions hold

larger in magnitude than -2 as well.

of any behavioral response depends partly on whether the shock

as

The example

permanent or temporary.

economic theory suggests

that the product

VI.

A

be larger than short-run

the other hand, the magnitude

viewed by workers and employers

in this section takes all elasticities as fixed,

whereas

market response to permanent income shocks should be

larger than the response to transitory shocks.

likely to

is

On

elasticities

Similarly, long-run elasticities of labor

demand

are

of labor demand.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

range of graphical and

statistical

evidence supports the claim that exogenous decreases

Palestinian labor supply are associated with an increase in the

workers.

IV estimates of demand equations

specification, but the best-fitting

Palestinian

Palestinian labor ranging between

"Supply

somewhat

models consistently suggest

wages and days worked can be

demand shocks by

are

wages

rationalized

Israeli

by a short-run

—1 and —2. Even

employers pay Palestinian

sensitive to the details of

that the

in

model

observed covariance between

Israeli elasticity

of demand for

simple IV estimates that do not control for

18

quasi-differencing imply a short-run elasticity of between -3 and -4.

elasticities are

assumed to be equal for both

locations,

and

cross-elasticities equal to

minus the own-

location elasticity. Another assumption used to construct the figure is that the share of local earnings in total

labor earnings

(<t>)

is

fixed at

60

percent.

"This finding contradicts those in Fishelson (1992),

log wages on the

number of Palestinians employed

macro model for a long time period

that

who reports a positive coefficient from a regression

in Israel.

ends in 1986.

of

But his estimates are from a large multi-equation

The Fishelson

results therefore

do not seem

directly

18

More and

better data

on the Palestinian labor market may

work. In the meantime, the results presented here suggest

more robust

results in future

market policies

in the territories

lead to

that labor

should be analyzed with a number of possibilities in mind. First, and most important, short-run

Israeli

demand

for Palestinian labor

from reduced access

may be

inelastic

enough

to considerably

to the Israeli labor market, at least for a while.

A

dampen

the earnings loss

Palestinian social planner

might even choose to exploit the resulting monopoly power by deliberately restricting supply. Of

course, social planners would also consider factors like the distribution of unemployment and the loss

of

skills

among

the unemployed.

Such consideration might well outweigh simple calculations

designed to maximize earnings or income tax revenues.

Finally, the use of a

model and associated empirical

results for forecasting is

future economic circumstances are likely to be similar to past circumstances.

emphasize

setting

this in a

most helpful when

It is

important to

study of Palestinian-Israeli labor relations because behavioral responses in this

depend partly on whether

local residents

and

Israeli

employers perceive shocks as transient

or permanent. Since the strong transitory shocks studied here are probably unusual, changes in access

policy that

different

come about

as part of a deliberate regime shift could

from those of past shocks.

comparable to those reported here.

have labor market consequences very

19

Table

A.

Descriptive Statistics*

1.

Sample

Years of

Size

Schooling*

Wage

LFP

Age

earner

Work

Days

worked

Married

22.2

0.67

0.47

in Israel

Residents of the Gaza Strip

1981

7,854

7.61

33.0

0.78

0.50

1982

8,223

7.92

32.6

0.77

0.51

21.9

0.68

0.48

0.50

21.6

0.66

0.50

0.50

21.9

0.66

0.49

1983

8,228

8.18

32.7

0.76

1984

8,930

8.33

32.9

0.76

1985

9,271

8.40

32.7

0.77

0.51

21.7

0.67

0.50

1986

9,743

8.69

32.4

0.77

0.51

22.3

0.66

0.49

1987

9,692

8.62

32.7

0.80

0.52

22.0

0.69

0.49

1988

6,932

8.48

32.9

0.79

0.49

16.9

0.70

0.48

1989

7,830

8.52

33.3

0.77

0.45

15.6

0.71

0.42

1990

8,892

8.63

33.2

0.80

0.47

16.5

0.73

0.44

1991

8,011

8.80

33.2

0.80

0.48

17.2

0.75

0.41

B. Residents of the West

Bank

1981

21,768

7.66

33.2

0.70

0.47

21.9

0.64

0.36

1982

21,992

7.82

33.3

0.72

0.47

22.4

0.63

0.36

1983

22,734

7.90

33.3

0.74

0.47

22.1

0.64

0.38

1984

23,807

7.98

33.3

0.76

0.48

22.1

0.63

0.38

1985

25,038

8.11

33.1

0.76

0.47

21.8

0.62

0.36

1986

26,394

8.26

32.9

0.79

0.48

22.2

0.62

0.35

1987

29,530

8.27

32.8

0.81

0.52

22.5

0.63

0.40

1988

27,593

8.36

32.7

0.83

0.52

18.1

0.63

0.40

1989

27,462

8.48

32.6

0.83

0.53

18.9

0.64

0.41

1990

27,773

8.49

32.8

0.82

0.52

19.5

0.66

0.39

1991

26,128

8.60

32.7

0.80

0.51

17.4

0.67

0.39

'

Statistics are

Sample

unweighted, except for the

size:

observations.

last

373,825 men aged 18-64

two columns which are based on weighted counts.

in

the sample period;

one-quarter of these are independent

20

Table

2.

Daily

Wage

Equations (Selected parameter estimates)*-

Work

Educa-

Educa-

in

tion

tion

Israel

13-15

16 +

(1)

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

(2)

Industry

(3)

wage

effects

1

4

5

Agri-

Manu-

Cons-

Servi-

culture

facturing

truction

ces

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

0.166

0.229

0.392

-0.214

-0.076

0.095

-0.118

(0.007)

(0.007)

(0.018)

(0.011)

(0.011)

(0.012)

(0.012)

-0.077

0.167

0.191

0.346

-0.215

(0.007)

(0.015)

(0.017)

(0.014)

(0.01231)

0.066

-0.136

(0.011)

(0.012)

0.150

0.156

0.340

-0.133

-0.039

0.094

-0.100

(0.007)

(0.014)

(0.016)

(0.013)

(0.011)

(0.010)

(0.012)

-0.003

0.127

0.308

-0.321

-0.121

-0.005

-0.139

(0.007)

(0.012)

(0.015)

(0.013)

(0.011)

(0.010)

(0.012)

0.006

0.117

0.250

-0.246

-0.087

0.014

-0.105

(0.007)

(0.012)

(0.014)

(0.012)

(0.011)

(0.010)

(0.011)

0.123

0.086

0.222

-0.148

-0.038

0.097

-0.038

(0.006)

(0.011)

(0.014)

(0.012)

(0.010)

(0.010)

(0.011)

0.189

0.055

0.225

-0.056

0.029

0.126

-0.006

(0.006)

(0.011)

(0.013)

(0.012)

(0.010)

(0.010)

(0.010)

0.248

0.009

0.145

0.006

0.050

0.190

0.022

(0.006)

(0.010)

(0.013)

(0.012)

(0.010)

(0.010)

(0.011)

0.336

-0.001

0.116

0.087

0.063

0.216

0.047

(0.006)

(0.010)

(0.012)

(0.012)

(0.010)

(0.010)

(0.0U)

0.312

0.055

0.156

0.089

0.058

0.215

0.038

(0.007)

(0.010)

(0.012)

(0.012)

(0.010)

(0.009)

(0.011)

0.357

0.041

0.164

0.046

0.049

0.201

-0.022

(0.007)

(0.010)

(0.012)

(0.012)

(0.011)

(0.010)

(0.012)

'Estimates of equation (1) in the text. Sample size for

public and

1'

community

services.

Standard errors in parentheses.

Sample weighted by

all

years combined

CBS

=

173,588. The omitted industry

sampling weights.

is

Table

Relationship Between Daily

3.

Wages and Days Worked by

Agric.

All

OLS

Manufact.

Construct.

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

-0.17

-0.14

-0.11

-0.08

-0.16

-0.11

-0.13

0.02

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.07)

(0.02)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.02)

(0.06)

(1)

A.

Industry (undifferenced equations)*-*

(8)

Estimates

Days

worked

Log average

employed

daily

wage of Israeli

citizens

in:

Construction

Agriculture

0.19

0.75

(0.07)

(0.03)

0.35

0.72

(0.07)

(0.06)

Manufacturing

1.0

(0.15)

B.

IV Estimates

Days

worked

Log average

employed

daily

-0.28

-0.23

-0.22

-0.15

-0.30

-0.22

-0.21

-0.10

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.03)

(0.03)

(0.02)

(0.02)

(0.02)

(0.04)

wage of Israeli

citizens

in:

Construction

Agriculture

0.43

0.73

(0.07)

(0.03)

0.09

0.70

(0.07)

(0.06)

Manufacturing

.60

(0.16)

Over-id x2^)

173

41

48

11

199

32

39

35

The

top panel reports OLS estimates from regressions of the log of real daily wages for Palestinian men

employed in Israel on quarter dummies, two Gulf War dummies, average log days worked in Israel, and log

real wages of Israeli citizens by industry. The Israeli wage series are quarterly by major industrial sector, from

the National Insurance Institute. The bottom panel reports IV estimates from the same specification using linear

and quadratic terms in person-days under curfew in the West Bank and Gaza Strip as instruments. The sample

includes 39,806 observations on Palestinian men employed in Israel: 5,603 employed

employed in construction, and 11,921 employed in manufacturing.

''Standard errors in parentheses.

in agriculture,

22,282

c_

u

11

?s

b

«

IfS

•o

£

£

2 >

o

&

CM 3

— 6

«1 ao

>«

o

s

2

C-

c-i

2?-

ON

i

S

9

d

V)

1)

"2

«

e e

§1

ii

£>

On

—

NO

—

d s

cm P.

^

"" 2.

©

d

r~

3

oo

eqi

are

d

>

1

regressors

estimating

P

2

en o

CO

d o

to

V

On

£

d °

ON

PI

§3

d

d

o,

NO

ON

00

CM

o

ON

O

1

i

i

^5

£

CO

o

*»

3 «

S *>

^

1

a

©

II

p>

U

cm

cm

©

p

S

2?

o,

9

<=>

"1

00 _g

tO

r»

—

PI

l"

e.

3 s

i

.5

wo

CM

d

o

s.

=f

o ©

On

£

d

9.

g »

s'e|

5 2 H

o C oo

S « a

<^ "2

>s

111

"1

3

>>

>»

M 1

s

.2

-

°-8S

O

e

d

9.

o>

00 go

7^

g.

d

2

st

ON

O

r

a

indust

CM

same

averages

d

the

across

is

annual

II

£>

— —

p

«*»

-

— 6

<

o s

—6

w> J?

CM

§

d©

NO

s

^m

0\

m

CM

ne

and

i

sai

are

l"

Israel

r

the

irs

1

$2.3

o

.0

1

a.

c

S.2-8

CO

^a,

g-w-

i

-—

d©

*

ae

ds

d

9's

CM

CM

CM

i

11^

•o

2

w

i

Q

I

m

o

II

g>

d

s.

3f

de

CN

CM

CM

r~!

do

intere!

alestini;

i

f

aO(L

in

1

See

wu O

IA

**

CO

S

text,

o

U]

08

in

CM f?

NO -

.2

7

<

<•>

1

5

00

U"N

^2

2§

d

s.

aramet

d

s.

uation

d s

ations

2;

§

>

•*•

*•

sr £

•o

2

o

s

.* xi

o

the

39,806

Estimates

o

X

1

and

•o

E

z

»

I

1

S

a.

P-

w

1

X

<5

dummies

includes

Notes:

t

I

u/

23

30

1

1

1

n

25

ii

ii

ii

ii

I 20

S

1

jlfl

Ii

cB

1

ii

•

i

A/i

8

|

1

Hi

i.i

i:i

i

15

y\

isi

\

f\\

ili a / \ »

I \

I fcv

111

li A M•111

1

1

1 • / V r* 1

'I

'1

\ «

A

V

i::i

mi

l.'Sl

I! SI

1

10

i

n

'*"•-•

.

n

'I

a

'/»

•

f

/*

I

/ i

*- —yv^ A

/•**

a

a

V^i"

A

'^A^AuA ^"V\\>^"

AV\

yXV

nArJ^vw

•»'/^'yvVAn'A4

5

1

«•* \

\/

>

li.il

\yi # n'i/yi

v\\/ yVfti

\

t

u

w

— y^A

...,,-

Figure

1.

1962

1983

Absences from Work by

1984

1985

Men Aged 18-64

1986

in the

1987

1988

IV*

1/

S

i

"-'

'

1989

1

*

i

'.

»

1981

A>i

•TV

•

a

#

lit*

•«

U

1

1

-

'X

1990

1991

Labor Force.

4.5

4.0

Gaza

West Bank

3.5

J

i

1981

Figure

2.

1982

Extra Hours to Get to

1983

Work

1984

in Israel,

1985

1986

1987

1988

i

i

1989

i

i

i

i_

1990

by Region.

Tabulated from reported hours of work by region and work location; excludes Gulf-War quarters.

"91

24

'^

65

r

J

Israel

60

——— W

.._._._._.

T

fl

fl

ft

#

1

tt

8.

s*

50

fl

x '

•

A>

i

fl

»t

*..

/L\l

/I*

. *

'1*1

A

'

•

//

\

-

V

\

v

\^

40 U K

v »-

\\

*/

•

«

*/

A

\

/

.-A

v*

\

\

1

*

V"

/

v \

\

v

y

i

i

i

i

1981

Figure

3.

i

i

i

i

1982

i

i

i

i

1983

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

\

\

*

-

V

1/

*"*

\A

V \

\

i

\

1

\

35

VvA\\\

\

1

r-v

i

#

t

»

1

I

v

/

"

i

\

\

»

»

»Vi

1

\y

x

i

*

*

\

\~

.\

•

»

\

i

/\

1

'"

•'

\

V

1

•

45

»>.»

f\

A///"n /

\AV^**V?\\

>M/&/\M\A«

Y-'/ I

v

*>. ,-/ V

/y

5\V

r^»^v

s \v /

ai

i

.a<

Xx\

»

\

Xj*

* /

\

»

/r\ /

/

/' V^ *«^

i

•

A

f

f

/./A

i/

if // 11

»

i

#

.

»

t

t

i

i

>

11

»».

f

_

i

%

/

i

>

t

f

ff

/ 1

I

x ~—_,A

\

1

•

#

1

/

i

i

i

/

/t

•

\

\

!

1

.

•

55

\

f\

SiBm

Bank

n.Dann

i

1984 1985

i

i

i

i

1986

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

1987 1988

i

i

i

i

1989

i

i

i

i

i

1990

i

i

100r

80

Curfews

Disturbances

60

40

-

°

-

r—

1987

1988

4. Disturbances and Curfews in the

Data from Palestinian and IDF sources.

Figure

Territories.

1989

1990

i

1991

Real Daily Wages by Work Location.

20

,

1991

25

••

0.15

-

0.10

-

06

—

•

°

|

f

J

-

^^^^

006 -

•

^^^"^

•

-o.oo

•

•

•

•

•

-O.10

-

-0.16

-

•

••

•

•

i

-

Figure

5.

-4

5

-3

-2

-1

O

1

2

Thousands of parson-days undar ourtaw

Curfews and Israel/Local Differences

•

in

3

4

(i

Daily Wages.

•

•

0.1 o

•

COS

I1

^_

TS^^

f

£

a>

•

0.00

•

•

-O.OS

*

••

-O.IO

-B

-4

-3

•2-10

i

1

2

Thousands of parson-days undw ourtaw

Figure

6.

Curfews and Israel/Local Difference

in

Days Worked.

3

4

1i

26

0.56-

m

0.50-

0.4S-

5,

.2*

0.40(

f