Document 11163322

advertisement

ww. r. LIBRARIES

-

DEWEY

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/emergingmarketchOOcaba

hU5 61

•

VE

WHI5

working paper

department

of economics

Emerging Market Crises: An Asset

Markets Perspective

Ricardo Caballero

October 1998

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass. 02139

WORKING PAPER

DEPARTMENT

OF ECONOMICS

Emerging Market Crises: An Asset

Markets Perspective

Ricardo Caballero

No. 98-18

October 1998

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF

TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASS. 02142

LIBRARIES

Emerging Markets

An

Ricardo

Asset Markets Perspective

J.

-<

Crises:

Arvind Krishnamurthy*

Caballero

This draft: November

5,

1998

Abstract

Although internal policy mismanagements can be cited in most recent emerging

market

crises,

they seldom account fully for the severity of these

crises.

The

reluc-

tance of international investors to provide the resources that would limit the extent of

the reversal, almost invariably plays a key role in bringing a previously (over?)-heated

economy

to a costly halt. Domestic assets experience dramatic depreciation

and other-

wise solvent investment projects and production, especially in the nontradeables sector,

find

no

down

financiers

and are wastefully shutdown. Ultimately, the reason

of a country's access to international capital markets

(real or perceived) of its international collateral.

sufficiency

and

its

We

build

must he

for this break-

in the inadequacy

a framework where

this in-

consequences stem from microeconomic contractual problems. Fire

sales of domestic assets naturally arise as the result of desperate competition for scarce

why the private sector does not take

international collateral when crises are likely. The answer lies

international collateral. This begs the question of

steps to ensure sufficient

in the presence of a pecuniary externality.

We show that contractual problems also lead

to a problem of insufficient domestic collateral, which restricts the transfer of surplus

arising

from the use of international

international collateral.

also sheds light

there

is

The

on when

collateral

between the users and providers of

interaction between domestic

pre-crisis capital flows

Capital flows,

collateral

ought to be regulated and on whether

scope for currency support measures during the

Keywords:

and international

this

fire sales, financial

crisis

or not.

constraints, wasted collateral, ex-

cessive leverage, collateral underprovision, real depreciation, asset deflation, financial

intermediaries, stock market

"Respectively:

and currency support,

MTT, AEI and NBER; Northwestern

participants at the

IMF, MTT, Northwestern and the

suggestions. Ricardo Caballero thanks the

NSF

interest rate policy.

University.

EFG-NBER

for financial

We

thank V.V. Chari and seminar

(conference) for their

comments and

support and the Research Department at the

IMF, where part of this work was accomplished. E-mails: caball@mit.edu, a-krishnamurthydnwu.edu.

draft:

August 1998.

First

Summary

Motivation and

1

Asset markets view.

In contrast with the disagreements on the causes and appropriate

responses to the ongoing Asian

by international

role played

crisis,

there

is

substantial consensus on the mostly negative

capital markets during the crisis

The

itself.

reluctance of inter-

national investors to provide the resources needed to smooth the impact of a combination

of internal

and external

demand fell,

external

deficiencies, dramatically

external credit

—and capital flows

real sector, especially nontradeables, to

preciations

what was

a virtual

halt.

in general

1

— vanished, bringing the

Asset deflation and currency de-

—as symptoms and consequences— took unexpected proportions,

justified

light of the crisis."

is

"well

beyond

by any reasonable reassessment of economic fundamentals, even

in the

2

Although a very dramatic one

Asian crisis

worsened the situation. As internal and

just the

for its relative surprise

and extent of "contagion," the

most recent chapter of an increasing trend toward shifting the "blame"

from current to capital account

issues.

Many think that

this trend is

side effect of increasing globalization of capital markets.

ually tilting policy advice as well.

traditional policy advice

on the

While large

an almost unavoidable

Such change of emphasis

real devaluations

grad-

were central ingredients in

seems to be increasing

face of external imbalances, there

concern with the possibility that "too much of the medicine

is

may

kill

the patient."

Cur-

rency boards and interest rates hikes to shore up the currency in the midst of severe crises

are

common

advice these days, often even coming from the staunchest former advocates of

devaluations. Markets also have spoken loudly at times;

on Black Thursday (September

10,

1998) the Brazilian stock market plummeted by nearly 15 percent. In a desperate measure

to stop the hemorrhage of capital flows, the authorities raised interest rates from 30 to 50

percent...

and the stock market responded with a 13 percent rebound. 3 Largely due to the

central role played

different

by

capital flows, economics of emerging markets

is

sometimes radically

from that of developed economies.

Gradually, the traditional "goods markets" view of external crises and their solution

is

being replaced by an "assets markets" view.

imbalance

is

no longer to simply devalue the

to reallocate consumption

real

The

central issue in resolving

an external

exchange rate and allow the private sector

and production to restore

real activity

and external accounts.

Although certainly an important factor in the long run readjustment of an economy,

1

For the crisis-countries

this

—Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand— net capital flows

declined from 73 billion dollars in 1996 to minus 11 billions in 1997.

The

actual decline in net inflows was

probably higher since "errors and omissions" went from -8.5 billions in 1996 to -19.5 billions in 1997.

2

World Economic Outlook,

3

The

May

1998, p.4.

leading international article in the Wall Street Journal

Big in Winning Back Foreigners."

on September 11 was

entitled: "Brazil

Bets

relative price ingredient

subordinate to the short run movements in asset prices and their

is

feedback into real activity - a link which, in our view,

magnitude of

and our

crises

In this paper

Goals.

ability to control

we develop a framework where

answer many of the questions surrounding

is it

them.

is

crises in

at the core of understanding the

4

asset

during

these affect real activity?

why

crises,

why

emerging economies. In particular,

Why

that foreigners are unwilling to finance these crises?

How do

markets take center stage to

do

assets' fire sales occur?

providing the financing

If foreigners are reluctant in

doesn't the domestic private sector take steps to ensure profitability

during these times by provisioning against them?

from the point of view of crisis-prevention?

Is

Should currency and assets be supported during

The inessential and

there a role for regulating capital flows?

crises?

Our framework

the essential.

the productive structure appropriate

Is

reflects

our view that a core component

of the answer to these central questions does not depend on the intertemporal substitution ingredients

economies

—

i.e.

we normally emphasize

in macroeconomics.

The very

fact that emerging

— normally run

economies whose future looks brighter than their present

very small current account deficits

—

to 10 percent of

in the order of

GDP,

rather than

— indicates that they are nor-

150 percent or more, as they should in a neoclassical setup

mally severely financially constrained.

Deep

crises are just times

are overwhelming. Instead, our answers to the questions

when such

constraints

we posed above build around the

simple and sufficient premise that, ultimately, the reason for the breakdown of a country's

access to international capital markets,

must

lie

in the inadequacy (real or perceived) of its

international collateral.

But what

Collateral.

is

international collateral?

can be valued and seized by foreign investors in

sical as well as

the Sovereign Debt literatures

At a basic

lieu of

The

literatures

on debt

crises,

anything that

promised repayments.

The Neoclas-

make some proportion of the present value

of net exports (or exports alone) the central answer. 5 Although

4

level, it is

it

highlights

a fundamen-

currency speculation, and bank-runs, offer important insights on different

aspects of assets markets during crises. Most of the effects in these literatures are either amplified or

more

likely

by the

(1994, 1996);

issues

on debt

we emphasize

crises see, e.g.,

in this paper.

For papers on currency speculation see,

e.g.,

made

Obstfeld

Calvo (1988), Giavazzi and Pagano (1990), Cole and Kehoe (1996);

on bank runs see the canonical Diamond and Dybvig (1983) and' the applications to open economies by

Goldfajn and Valdes (1998) and Chang and Velasco (1998a). Also see Calvo (1998) for an overview and

interesting discussion

on implications and sources of

worth pointing out that, while

insightful

possibility of multiple equilibria,

the

5

crisis

must be

left

and

unexplained

capital

and probably very

market

relevant,

crises in

small open economies.

a central issue in these papers

in so doing this literature admits from the outset that

(i.e.

a

It is

is

the

large part of

to "sunspots").

See Bulow and Rogoff (1989) for a canonical model of international debt capacity based on the amount

of "punishable" future trade flows

and exports.

tal constraint, this

On

scenarios.

answer

one hand,

is

among very

incomplete

central dimensions of

modern

crises

does not capture the idea that an excessive devaluation

it

be harmful for international

collateral.

6

On

may

the other, in today's emerging economies the

private sector carries the lion's share of international borrowing, thus microeconomic rather

than representative-agent

frictions

ought to be at the roots of the problem. Our model gives

market constraints arising from microeconomic contractual problems

central roles to credit

in the process of creation

and aggregation of international

Domestically, collateral

is

created by the corporate sector

claims on firms in the nontradeable

—

understood

limit the

in distress.

The

and tradeable

number of claims that

to obtain external financing

situation

is

when

in need,

by international

International collateral

and shares on

sector, while claims

assumption captures

by Mexico when their

liquidity package it received

investors (e.g.

6

limits

on

is

made of financial

problems

—broadly

firms can issue, affecting both their ability

collateral to other firms

collateral.

when not

8

In most of our analysis

the tradeable sector.

international collateral

is

on both sectors count as domestic

Very

realistic biases.

directly,

that cash revenues from exports can be seized before they

feature used

and

itself,

sectors. Contractual

and to supply

make a simple broadbrush assumption that

stylized, this

7

worse with respect to foreigners, which only accept a subset of

these claims as backed

on the tradeable

collateral.

oil

made

revenues were

during the 94-95

crisis,

real estate investments).

make

it is

it

we

restricted to claims

collateral.

justified

Although

by the

fact

back into the country, a

part of the collateral backing the

and by mandate on foreign institutional

9

More

indirectly, this

assumption

is

a

Quite the contrary, an excessive (real) depreciation should build more international collateral and further

entice foreign investors to finance the crisis.

Of

course,

if

concerned with this specific issue alone, one could enrich the story by adding a financial

sector which

is

over-exposed to the nontradeable sector, and plays the role of an input into production of

tradeables.

Still,

one needs to address the question of why banks are over-exposed to begin with, and how

an excessive depreciation

7

According to the

is

IMF

an equilibrium outcome.

(1998, pp.

63-64),

a distinguishing

purely macroeconomic considerations has played

et

al.

a

lesser role

characteristic of the current crisis is that

than in previous

crises.

Also, see Johnson,

(1998) for stark evidence on the correlation between weak corporate governance and institutional

environment

(i.e.

a weak contractual environment)

in

an economy and the incidence of the current

crisis.

As the corporate finance literature has demonstrated, weak corporate governance and, more generally, weak

hand in hand with credit market

an extensive literature documenting "home bias"

contractual enforcement go

8

There

1991),

is

matched by asymmetric

reasons behind

home

bias, as

constraints.

in asset holdings (see, e.g.,

information explanations (see e.g.

most countries

Zhou

French and Poterba

1998). There are also institutional

limit foreign ownership of domestic companies.

range from constraints on a few "strategic" sectors

(e.g.

oil

and telecommunications), as

These

limits

in the U.S., to

across-the-board constraints, as in pre-crisis Korea.

9

Of course there are important exceptions

(1997) for systematic

(e.g.

"too big to

Japanese evidence showing that,

fail" utilities),

but

see, e.g.,

for small firms, those that are

Kang and

Stulz

export oriented are

very efficient mechanism to capture the central implications of an expanded model where

foreigners' collateral-bias

is

only against small firms and current production of perishable

nontradeable goods (see the appendix).

Financial Transactions.

Financial claims in our economy consist of equity shares issued

by tradeable and nontradeable

be traded

may

freely.

10

own

issue its

Thus, a firm in the nontradeable sector in need of funds, for example,

may have already owned,

it

nontradeables firms' shares in

reshuffling of collateral

its

as well as the proceeds

is

assumed to be

(firms) are subject to aggregate

which accumulate to determine a country's net import needs.

— such needs,

these,

from

possession, as international collateral. This

through stock market transactions

Domestic entrepreneurs

Shocks.

and use

shares in exchange for shares in the tradeable sector

together with any tradeable shares

selling other

Stock markets function perfectly, so these shares can

firms.

costless.

11

and idiosyncratic shocks,

International funds

must

finance

—

lateral.

Although the mechanisms we emphasize magnify the impact of aggregate surprises

—be

a decline in terms of trade, in foreigners'

it

in full or part

ness, or in

banking capital,

surprises are distinct

etc.

brought about by these

break down. First, a country

may fail to

aggregate international collateral properly;

by shocks have severe agency problems and/or scarce

collateral provisions,

be constrained by domestic collateral well before the country has used up

favored by foreign investors. See, e.g. Blommestein (1997), for a discussion of

assets considered highly illiquid or

by foreign

institutional investors.

10

for

how

may

if

firms

they

may

all its

real estate

available

and Other

exposed to exchange risk are generally avoided (sometimes by mandate)

Interestingly, the very

few exceptions to the sovereignty principle, by

which the rating on debt issued by a country's corporate sector

government debt rating, are

we

until the last section of the paper.

In our framework, there are two stages at which the "credit chain"

Bottlenecks.

hit

issues

In order to highlight these differences,

insights.

col-

"risk appetite," in external competitive-

— the hedging and insurance

from our main

assume no aggregate surprises

which foreign investors demand international

for

is

bounded from above by that country's

companies which belong to the export

In this sense, individual foreigners

may

sector.

hold shares on firms in the nontradeables sector, but the total

value of foreigners' holding of shares in tradeables

and nontradeables must not exceed the

total value of the

pledgeable shares in the tradeable sector.

Some words

a

far cry

of interpretation are in order.

Our

from the reality of emerging markets.

usual form of financing in most economies.

focus purely

First,

on

frictionless equity

Qualitatively,

is

like.

is

not an interesting

Second, the reshuffling of collateral in an emerging

more often done by the banking system than

directly

by

firms' trades in

adding richness by modeling the role of intermediaries in these transactions

these transactions are costless in our model, which

implements them.

certainly

debt rather than equity contracts would aggravate many of the effects we describe

by introducing debt overhang problems and the

economy

is

and with a few caveats that are not central

to our story, whether external financing takes the form of equity purchase or debt

distinction. Quantitatively,

markets

debt contracts rather than equity are the more

means that

it is

a stock market. Again,

is

not central to our insights. All

irrelevant

whether a creditor or borrower

international collateral. 12 Second, even

if

aggregation can be done

the international

fully,

collateral creating sector

may

not be able to generate enough pledgeable shares to finance

the

more

likely as contractual

crisis; this

scenario

is

problems in this sector

rise.

We refer to

these as domestic and international collateral problems, respectively. Given institutions

contractual problems, which constraints the

aggregate shocks. For mild shocks

the domestic constraint

one

likely to

is

become

is

economy encounters depends on the

—perhaps "normal" times

likely to bind, while

and

severity of

an emerging economy

for

during deeper recessions the international

active as well.

the latter scenario, with the simultaneously binding constraints, that accounts for

It is

the most dramatic differences between crises in developing and developed economies, and

in the appropriate policy response to these crises.

Equilibrium Prices and Fire Sales

falls

Once

one region or the other depends on the relative price of domestic and interna-

into

tional collateral.

Other things equal, as the relative price of domestic collateral

likelihood of wasting international collateral

equilibrium price depends to a large extent

As the

other.

whether the economy

in a costly crisis scenario,

falls.

On

is

in

one region or the

becomes more binding, the

relative price of

domestic collateral declines rapidly as competition for scarce international collateral

Indeed,

we show

that a fire sale of these shares, by which

below their fundamental value,

constraint.

13

is

the

the other hand, the behavior of this

on whether the economy

international collateral constraint

rises,

we mean a

rises.

decline of their price

a natural consequence of a binding international

collateral

In our model, this sharp decline in the domestic share prices can be thought of

as the combination an "excessive" depreciation of the real exchange rate

and a substantial

widening in the domestic-international interest rates spread.

On

Collateral underprovision.

the face of these potential

fire sales,

the question arises as

to whether they are not sufficient incentive for the private sector to reallocate factors of pro-

duction to collateral creating sectors to benefit from the additional international collateral

value of their shares.

and increase

The

its

We find

that indeed the private sector will value collateral provision

supply, but generally

it will

not do as much of

it

as

is

socially optimal.

source of the externality behind the undervaluation of collateral provision

ing in

itself,

for

it is

is

interest-

the result of the interaction between the domestic and international

credit constraints. Despite fire sales, the domestic credit constraint limits the transfer that

l2

This

equivalent to the "wasted liquidity" in

is

collateral"

Holmstrom and

Tirole (1998), although oui "wasted

has implications for pre-crises policies not present in theirs, which stem from the two-goods

nature of our economy.

l3

This definition of a fire sale

is collateral

assets as

constrained, prices

we assume that

is

similar to that of Shleifer

must

fall.

and Vishny

(1993).

When the domestic economy

However, unlike Shleifer- Vishny there

foreigners will never hold claims

on the nontradeable

is

no outside bidder

firms.

for the

firms in distress can

constrained

demand

make

The

to suppliers of international collateral.

anticipation of this

for international collateral reduces the incentive to create

Contrac-

it.

tual problems in collateral providers generate the fire sale, while contractual problems in

distressed firms act as a disincentive

is

collateral provision.

Even

Overinvestment in nontradeables.

as

on

additional international collateral

if

the case in the milder wasted collateral region,

benefit from reallocating resources

reallocation

we argue

that the

is

economy would

from the nontradeable to the tradeable

would appreciate the long run

exchange

real

not needed,

Such

sector.

rate, boosting the collateral value

of nontradeables shares during the crisis period. Individual investors in the nontradeables

sector do not internalize the negative effect of their investment

These externalities

Capital flows.

may

economies predictably run into systemic

pre-crisis capital inflows

this question

or in the

since individuals

The

crises.

can exacerbate these

fire sale

is

more

We

fire sale

of insufficient international collateral,

all

Policy.

wasted

collateral

and

region,

this

is

collateral aggregation value of

a

real

on the other hand, the problem

is

one

aggravated by pre-crisis capital inflows.

where domestic and foreign return

when this differential is large. The standard neoclassical

is

a natural obstacle to

differential is low, it is

not

arbitrage of relative productivity

overwhelms the collateral provision enterprise, making severe crises and

the more

whether

show that the answer to

likely to fall in the

Although the equilibrium domestic collateral provision premium

differential

is

region. In the former, equilibrium capital flows are insufficient

exchange rate appreciation. In the

so

why emerging

natural question to follow

externalities.

do not take into consideration the

capital inflows in situations

collateral value.

harbor some of the answers on

depends on whether the economy

more severe

on others'

fire sales

likely.

Since the outcomes of our simple structure are certainly rerniniscent of the events

and dilemmas faced by emerging economies,

of discussing policy implications.

of insurance contracts;

we

Many

it is difficult

to resist the naive temptation

of the natural policies in this setup take the form

relegate these to a secondary role because they often have high

informational and enforcement requirements which are not likely to hold well in emerging

economies.

Rather,

we

focus our attention on direct intervention in asset

markets, without attempting to differentiate

among

and exchange

asset holders within each type of asset.

Perhaps the clearest implication of our model in terms of policy

is

during the pre-crisis

period where subsidizing domestic investment in sectors that create international collateral

should be contemplated whenever the likelihood of falling into the wasted collateral or

fire sale

region

is significant.

Advice regarding capital flows

or taxing pre-crisis capital flows depends

international collateral

is

more

likely to

is

more ambiguous;

fostering

on whether the aggregation or the amount of

be the main problem in the event of a

crisis.

What can be done

during crises exacerbated by collateral constraints?

price of domestic shares, or lowering domestic interest rates,

problem

primarily one of insufficient domestic collateral.

is

may be

sures

transfers

if

In the

one of

is

Boosting the

in principle useful

But the

costs of these

high, since arbitrage conditions require persistent interventions

the exchange rate

fire-sales region

is

when

and

the

mea-

implicit

to be maintained.

the story

is

quite different.

insufficient international collateral,

Since the fundamental problem

is

boosting the price of domestic shares without

supplying additional international collateral or resources does not have any positive impact

by

Supplemented and financed with an increase in domestic

itself.

this

is

what

is

real interest rates

required for the government to attract foreign funds at the margin

—

if

— may

instead have favorable effects. 14

The

Collateral in macroeconomics.

international economics literature has long recog-

nized the importance of international collateral and

sector.

15

The Latin American debt

its relation

with a country's tradeable

of the 1980s led to the development of formal

crisis

models of sovereign debt renegotiation, and to the closely related question of what

is it

that

international lenders can threaten sovereign countries with in the event of a default (see

Eaton and Gersovitz

its

costs

is

(1981),

Bulow and Rogoff

and

mostly modeled as a country-wide phenomenon, the question immediately arises

on whether the domestic private

hood

(1989)). Since in this literature default

Bardhan

of these events.

sector internalizes the effect of their actions

(1967), Harberger (1985)

on the

likeli-

and Aizenman (1989) advocated

taxing capital flows on the grounds that individual agents do not pay for the increase in

a country's average cost of capital brought about by their international indebtedness. Our

results

on

capital flows

and

collateral underprovision

of the circumstances under which this problem

ommendation

can be seen as a formal description

is likely

to arise. Similarly, our policy rec-

in favor of subsidizing the tradable sector to increase collateral availability

is

akin to Borensztein and Ghosh's (1989) advocacy for subsidizing investment in the export

sector.

Although we touch on many of the insights of the

eling

and conceptual

closely related to the

differences with

new

literature

and Moore (1997) place the

it

are large.

on the

On

debt-crisis literature,

both our mod-

these aspects, our approach

is

more

role of collateral in macroeconomics. Kiyotaki

collateral role of

a fixed input

—land— and

its

distribution

across agents at the center of their amplification mechanism. Krishnamurthy (1998) shows

14

Generally, these policies have perverse effects

on the

incentives for collateral provision during normal

Krugman

(1998) for an

times. These should be offset with

some form of

account of the recent Asian

terms of a model that highlights the absence of such palliatives, together

crisis in

collateral creation incentive. See

with uncertainty about the government's willingness to provide "insurance."

l5

See, e.g.,

Simonsen (1985).

how a

richer set of contracts

than that allowed by Kiyotaki and Moore

shifts

the relevant

constraint from that which applies to individual agents to the total availability of collateral in the

economy. Holmstrom and Tirole (1998) argue that the stock market alone

provide insufficient collective collateral

if

not aggregated properly.

even when wasted corporate collateral (hquidity)

be required

in the presence of large shocks.

modeling aspects with each of these

with them as a group

is

not an

Although our

articles are plenty,

They

issue, public

also

and an international one

—

-

and

show that

supply of

it

differences in terms of goals

may

and

our central theoretical departure

our focus on the presence of two collateral constraints

is

may

their rich static as well as

dynamic

—a domestic

interactions.

Certain aspects of our model are similar in structure to models of liquidity in the banking literature

(Diamond and Dybvig

(1983)). In this light, underprovision of collateral

is

analogous to the free rider problems and underprovision of liquidity emphasized in that

literature (see Jacklin (1987),

Bhattacharya and Gale (1987)). However, the source of the

externality behind this inefficiency in our

tract laws

liquidity

and

institutions, while theirs is the

A second

by consumers.

believe that

bank

failures

is

the endogenous result of imperfect con-

exogenous divergent ex-post valuation of

departure from these models

rather than on banking arrangements

we do

model

and

their

fire sale

in our focus

on markets

key sequential servicing constraint. While

and runs can aggravate

the basic features of crises and their prelude arise even

Moreover, the

is

crises,

when

our model points out that

there are only stock markets.

mechanism we emphasize boosts the

likelihood of banking crises

themselves (see the appendix).

Outline.

the

Section 2 follows this introduction with a description of the model, starting from

crisis period.

It

analyzes and characterizes the critical wasted collateral

regions. It continues with

as well as with

an

and

fire sale

a discussion of the dangers of a weak domestic banking system,

illustration of the fragility

brought about by excessive leverage. Section

3 takes a step back and analyses the history preceding

crises.

In particular,

it

illustrates

the basic externalities leading to private undervaluation of collateral provision investment

and to overinvestment

by

in nontradeables. It

pre-crises capital flows. Section

4 discusses insurance markets and the shock structure.

Section 5 discusses policy implications

2

The

2.1

more generally and

concludes.

An

appendix

follows.

Phase

Basic Setup

Overview.

neurs

Crisis

then shows how these externalities are affected

who

We model the core of our economy as comprised by ex-ante identical entrepreuse their resources to begin companies in a tradeable and

a nontradeable

sector,

and to buy shares of other companies. Contractual problems

neurs' leverage, so that they

must retain a

fraction of their

limit the extent of entrepre-

own

shares. Entrepreneurs

do

not value diversification per-se, as they are risk neutral with respect to idiosyncratic shocks;

however they have a strong incentive to hold others' shares as

ing an idiosyncratic

collateral in the event of fac-

In equilibrium, residents are indifferent on whether to hold this

crisis.

form of shares on firms on the tradeable or nontradeable sectors (T- and

collateral in the

To start, we assume

N-shares, respectively).

N-shares as individual

collateral,

foreign investors are not; although they accept

they promptly swap these for T-shares in the market. 16

In emerging economies, marginal investment (and consumption)

We

capture this feature in a simple environment.

demand

their net

for tradeable goods.

Firms are

At the aggregate

existing shareholders. If the firm in need

to

be exchanged

collateral at its avail,

which also need to be swapped

very similar, although

the fully flexible period

structure,

and

fina.nr.ing

own

it

of which

The problem

economy

governance problems are

may be

may be

obtained by diluting

17

in the

new

shares have

The

rest has to

form of N-shares

of a firm in the tradeable sector

Time

is

indexed as

t

—

0,1,2.

Date

is

agents design the productive structure, ownership

Date

1

is

the

crisis period.

Date 2 represents the future

summarizes the cost of the crisis and realizes budget constraints.

issues are distinct

from the

chronology, and discuss crisis issues here taking history and

we

raise

issuance can be used directly as international collateral.

when economic

period;

some

lasts three periods.

interrelated, the date

the next section

If

in the nontradeables sector, its

for T-shares.

portfolio allocations.

and "accounting"

Although

its

The world

Basic setup.

by shocks which

for T-shares to serve the role of international collateral.

be financed with the

is

is

financed externally.

these shocks require external

level,

financing, for which foreigners require T-shares as collateral.

not too severe, a substantial fraction of the required

hit

is

discuss history formation.

crisis issues.

its

We

reverse the

"mistakes" as given.

In

Thus, for the purpose of this section, our

starts at date 1.

The domestic economy

is

populated by a continuum of unit measure of agents with

Cobb-Douglas preferences over date 2 consumption,

Where,

q

is

consumption of tradeable (T) goods at date 2 and c„

tradeables (N) at date

as e.

16

2.

2 consumption only,

of the roles the domestic financial sector plays, in our view,

is

we remove from our

Whether the borrower or

lender implements this transaction

10

analysis

in evening this asymmetry.

return to this issue below.

17

consumption of non-

We denote the date 2 exchange rate of T-goods in units of N-goods

By specifying preferences over date

One

is

is irrelevant.

We will

standard intertemporal substitution and smoothing arguments which are not central to our

approach.

On the production side,

how much

care

output at date 2

is

given to the existing productive structure at date

is

the total amount of capital devoted to sectors

from date

0.

the result of investments

At date

1,

production in a fraction p of the firms

goods at date

imports.

20

output of

Rnln

1 to contribute

19

at date 2.

at date

<

is

and

Let kn and kt denote

1.

N and T at the beginning of date

the N-sector, firms are required to contribute In

in order to realize

made

inherited

1,

interrupted by a shock. 18 In

kn additional units of the tradable good

The domestic economy

will

have no tradable

and the shock can only be accommodated by an increase

in

Besides heterogeneity, the two essential ingredients of our modeling of the shock

are an import need coupled with a margin

on which to adjust production. Because having

a second reinvestment opportunity does not add substantial additional insights,

we model

the shocks to the T-sector more simply as just resulting in lost output; firms that are hit

with a shock lose

by the shock

is

all

output at date

2.

Production per unit of capital in T-firms not affected

Rt.

Firms' investments in the two technologies are held as N- and T-shares. These shares can

be bought and sold at

all

dates subject to one important constraint. Because of an agency

problem (contractual problem) between an entrepreneur/firm and

each firm must hold at least a fraction 6n and

only the complements, 1

— 6,

6t

respectively of its

#o,t

As we

worth to

be the fractions that each firm holds in

These fractions are the

outside claimants,

own

shares.

21

Thus,

can be transferred within the agents in the economy. This

fraction constitutes domestic collateral. It has equal

Let #o,n and

its

result of date

decisions

and

its

all

agents in the economy.

own

technologies at date

1.

constraints.

said, foreign investors are willing to receive N-shares in

exchange for funds but

transform them immediately into T-shares. Thus international collateral constitutes only

the T-shares. These investors are risk neutral and have preferences only over the consump18

We

assume that the identity of firms receiving

this idiosyncratic

shock

is

not

verifiable.

This rules out

insurance markets against the shock. See section 4 for details.

19

Production has a time-to-build aspect. Investments are

possibility of scrapping the project or investing

made

at date 0; date 1 leaves firms with the

more resources in order to

realize

some of the output at date

2.

20

In the appendix we introduce production and consumption at date

with this extension and

obtain our

we can drop

fire sale results (see

1.

Our conclusions remain unchanged

the assumption that foreigners do not accept N-shares as collateral to

below).

The formulae

is

obviously more cumbersome, thus

we

leave

it

for the

appendix.

21

We

appeal to agency conflicts in making this "high-level" assumption. See the appendix for a deeper

justification of the assumption. Also, see

La Porta et

correlation between corporate governance problems

higher concentration

is

al.

(1998) for worldwide evidence

and ownership concentration

needed to prevent managers from

11

stealing).

on the high

positive

(in their interpretation,

tion of T-goods. Unlike domestics, foreign investors have preferences over

all

may be

dates because they

called

endowments of T-goods at

large

on to supply tradeable goods at date

count the future so that the preference structure pins

at zero. For now,

we assume foreign

investors have

They have

1.

we assume that they do not

dates. Additionally,

all

consumption at

down

dis-

the international interest rate

no positions

in

terms of domestic shares

at the beginning of the crisis period.

At the beginning

Initial conditions.

technologies, while the remaining 1

of date 1 firms hold #o,n shares in their

— #o,n

p of the N-firms are hit with a shock at date

replenish production

each firm that

is

up

to In

<

k„,

left

of the option to replenish production.

hands of the manager of the

their shares are worthless.

1 that leaves

— #n )(l — p)Rn,

Firms hold

We

assume that

of this at date

all

this option value rests purely in the

firm. Outside shareholders are fully diluted

shares in their

1.

shareholders of

upon a shock and

22

or each share repays (1

#o,t

The

to

with no value in terms of goods but value in terms

Given the shock, the shares on the market of the N-sector

(1

fraction

them with the opportunity

with an input of In tradable goods.

with a shock are

hit

A

held by other firms (the market).

is

own N-

own

The remaining

1

aggregate

will payoff in

— p)Rn.

Firms that receive the shock lose

T-technologies.

— #o,t

held in the market and repays per share of

is

(i-p)RtThus the

by a shock.

(1

total resources available to

A distressed firm

— p)(l — 6o,t)kt

T-shares at date

(D)

is left

a firm at date

with (1

shares of the T-sector. Let

1.

Then the date

1

depend on whether or not

— p)(l — #o,„)fcn

shares of the N-sector

a£

= (1 - p)(l -

o ,n)

1 collateral (in T-shares) of such

Decisions and constraints.

and wf

= (1 - p)(l - 60it

—

of shares to raise (1

— 9)In P

<

fcn-

Then

a

firm,

wd

,

is

(1)

).

it

can issue against this a fraction

shares of T-sector. However this share issue

to the constraint that the firm retains at least

>6n

of the firm also include its shareholdings in other

"Some

it

a

is

subject

fraction of the firm because of the

agency problem. In addition to the proceeds from the share

to convert a fraction

and

A firm in distress needs to raise funds to finance continuation.

Suppose the firm chooses to finance In

1

hit

P be the price of an N-share in units of the

w^KPuZ + ktcof

where,

it is

issue,

the available resources

N- and T-firms. Suppose that

it

chooses

of the N-shares of this holdings into T-shares so that these also

degree of dilution of external claims'

is

obviously

realistic.

We

have adopted an extreme form of

to exclude "debt overhang" problems from our discussion. In any event, expected dilution will be built

into prices at date 0.

12

constitute resources for reinvestment. Then, the total resources of the firm at date 1

The

this

firm chooses to sink In from these resources back into production.

reinvestment

first

is

on

= OlnRn + c(((l - 0)In P + OcknPui + k,f4)Rt - In)

term represents the

second term

profit

is,

7T

The

The

is,

fraction, 0, of

date 2 output that the firm retains.

the amount of resources that the firm

is

left

with after contributing In

The

firm maximizes this profit subject to budget

einRn

+ e(((l - d)In P + aKP^i + k u>f)R - /„)

towards saving production.

The

and

collateral

constraints,

max

S.t.

t

t

(1)

((l-eVnP + aknPcjZ + ktvfiRt-In^O

(2)

e

>

(3)

e

<i

(4)

/„

(5)

a<

en

<

K

1

Forming the Lagrangian,

l = einRn + ie+xMai-e^p+w^Rt-ij + Mie-On)-

M9 - 1) - Hln -K)- A

where the A's are multipliers on each of the

Let In , 6 and

by these firms

is

a

be solutions to

p((7n (l

5 (a

- 1)

five constraints

this problem.

Then the

the agency problem

of N-shares to

is

buy to

is

total

all

greater than zero.

number of N-shares sold

— 6) + cuJ^kn).

A firm that does not receive a shock is sound (S)

these N-shares. This

and are

paid for with

its

at date 1

and may choose to purchase

available shares of the T-sector,

the fraction (1— 6t) of its T-share holdings.

It

solve,

max

s.t.

e(Rtkt

- XPRt) + XRn

xpKktVo.t-et+ii-eojO.-p))

x>o

13

which because of

chooses

X, the number

Let

X{P) be

the solution to this program.

Equilibrium.

In equilibrium, the

number of N-shares

purchased by the sound firms. Thus, market clearing

(1

This condition gives the date

Date 2 exchange rate and

date

sold by the distressed firms

must be

is

- p)X{P) = p((l - B)In + auZkn)

1

equilibrium price, P, of an N-share in units of the T-shares.

collateral

premium.

Consider

now

the spot exchange rate at

Given the Cobb-Douglas preference structure, the exchange rate will only depend

2.

on aggregate consumption. The

first

order condition for a representative consumer yields,

Cn

Given /„,£„,&*,

= (l-p)Rn kn + pRn In

C„

C = (l-p)R kt-pIn

t

As we know,

of

T

t

P is the price to exchange claims on R„,

N for

units of

at date 2. Consider however the simple exchange at date 2 of

R units

of N for Rt

claims on

Rn goods

t

goods of T. Let the price of this exchange be P, which we refer to as the fundamental price.

Then,

P=

When

P y£ P,

there

is

a

collateral

—

eRt

premium governing exchange

at date

1.

Let

L

be

this

premium,

-I

we show

The

to the

in the next section that equilibrium will require that

strict inequality

rises

collateral.

Equilibrium requires that the return on holding

above that of holding international

collateral.

interpreted exclusively as a decline in the relative price of N-shares.

a

[fictional]

This need not be

To see

this, let

us define

date 1 exchange rate, ci, as the price to exchange 1 unit of the T-good for e\

units of the N-goods at date 1.

1 holding

1.

P < P holds if there is scarcity of international collateral relative

amount of domestic

domestic collateral

L>

Now

consider the investment decision of an agent at date

one unit of T-good and choosing between investing this in the domestic or the

international economy. Investing

the international interest rate

is

abroad just means buying international

collateral. Since

pinned down to be one, the return on this investment

14

is

one

as well. Investing domestically

of L.

The domestic

and an investment

means purchasing domestic

collateral,

which yields a return

transaction can also be implemented via an exchange rate transaction

at the domestic interest rate.

units of N-goods at date

The agent can

convert the T-good into e\

which can then be invested domestically at an interest rate of

1,

Rd, yielding Rd&\ N-goods at date

The

2.

return on this investment must be equal to L, or,

rAe = l

Thus, when

L>

1,

the domestic economy

must

these resources, domestic investment

>

we

In the next section

Wasted

2.2

Preliminaries.

w

which

d

is

(1)

need of foreign resources. To attract

1,

come

or in the form of an expected real exchange

and equilibrium

characterize decisions

in

more

detail.

and Fire Sales

Return now to the optimization problem of the distressed

>

and

0)

(4)

does not (A4

firms. Analysis

We focus our discussion on the case

depend on which constraints bind.

binds (Ai

either in the

23

Collateral

of this problem will

in

l.

in great

yield a high return, which can

Rd >

form of a high domestic interest rate,

rate appreciation, ei/e

is

= 0).

Constraint (1) will not bind only

if

very large, so domestic firms are sufficiently well capitalized that they are financially

unconstrained.

markets

like

While perhaps useful in classifying countries with well developed capital

the US, this constraint

is likely

the focus of this paper. Constraint (4)

net-present-value (henceforth,

constraint only binds

N-sector and

is

if

NPV)

is

to bind in the emerging economies which are

similar, in that

projects that the

it

represents the

economy

is

able to undertake. This

the economy has sufficient resources to save

thereby able to finance

all

of its positive

Differentiating the Lagrangian with respect to

amount of positive

all

production in the

NPV projects.

In we obtain that constraint

,

(1)

binds

as long as,

6(Rn

-e)+ e(l - 0)(RtP - 1) >

Saving a unit in distress in the N-sector is a project that creates

at a cost e, the value of

Rn/e which we assume

that

Rn/e >

one unit of tradeable. The social return on

is

greater than

l.

24

We

will shortly

then Ai

> 0.

show that RtP

Consider next the derivative with respect to

^ = PR (e(L-l)-\

t

1

this project is therefore

>

1,

implying

1 is sufficient for (1) to always bind.

If (1) binds,

23

Rn units of nontradeables

The model does not pin down Rd and ei/e because

6,

1)

in our formulation there

is

no goods market at date

through which an exchange rate can be established. In the appendix we introduce this market.

See appendix for assumptions on primitives that yield this result.

15

Our concern

is

mostly with regions where this expression

straint (1) binds 'Voluntarily;"

will

not be willing to use up

this region at the

end of

if

is

negative, for otherwise con-

the equilibrium price of N-shares

is

too low, entrepreneurs

N-shares to finance reinvestment.

all their

this section; for

now,

In

let

6

= 6n

and

a=

1.

We

will return to

Thus,

= jR wd

t

where,

lf

-i-(i-en )PR >0

t

and

7-Rf

Wasted

is

the return on internal collateral of a firm that

Region

collateral.

1 is

is

hit

with a shock.

the case in which the domestic collateral constraint binds

while the international collateral constraint does not, which happens as long the following

inequality holds:

p P ((i - en 1 R w d + Kwi) <

t

)

The left hand side

(henceforth,

LHS)

The

right

hand

side (henceforth,

There

is

off selling

financial constraints

factors govern

market

RHS)

is

(2)

for

T shares from firms

collateral in the

hands of distressed

the

demand

the supply of T-shares from the rest of the

an excess supply of T-shares, the price governing

must simply

for T-shares

is

- p))-

reflect the

exchange rate at date 2

(i.e.

P).

wasted international collateral in this region because, while the economy as a whole

would be better

Two

is

o , t )(i

t

of this inequality

domestic economy. As long as there

exchange of N-shares

- p)kt(0o,t -e + (i-

amount of domestic

that receive a shock. It reflects the

firms.

(i

is

more of

this collateral in order to finance this shock, domestic

on the firms that

poor

receive the shock prevent this collateral aggregation.

collateral aggregation. First, if

6n

is

high, the domestic financial

poor so that firms are reliant on their own resources. Scarcity of these resources

(low vf1 ) compounds this problem.

As aggregate

be

easily seen for

conditions deteriorate, the

an increase

in foreign cost of capital.

economy

into the

Fire sales.

25

in

p but

2,

of (2) rises relative to the

RHS;

this

can

can also be shown for a decline in Rt or an increase

Eventually, such decline in aggregate conditions brings the

more severe fire

In Region

it

LHS

sale region.

the inequality (2)

is

violated at the (fundamental) price P.

Excess demand for T-shares requires that the price of these shares in terms of N-shares

rises (i.e., that

fire sale region

25

P falls),

resulting in

a depressed value of N-shares.

We

refer to this as the

because the shock results in firms selling N-shares at prices depressed beyond

A decline in foreigners

"risk appetite"

can be easily built into our framework and has consequences very

similar to an increase in Ot; see below.

16

fundamentals. Investment (/„)

economy

is

primarily curtailed by scarce international collateral.

The

as a whole has T-shares of,

{i- P){i-et )kt

the international collateral constraint binds,

If

must be that

it

to foreigners to finance the shock so that reinvestment

In

of these shares are sold

all

by each firm

is,

= hRt—il - St)

P

However,

this equality derives

from general equilibrium considerations. Each firm chooses

P as given. Thus, the equilibrium value of P must fall until yRtWd falls to satisfy

P instead of P. We can write this equilibrium condition in the fire sale region as

r

In taking

(2)

with

1

=

-&Pu>Z+u?)

n

tJ

i-(i-en )PRt K h

where we have made one simplifying assumption and

^(l-6

(3)

t ),

P

let #o,t

= St

(we later show that date

optimality will ensure this relation.)

A

Equilibrium price and collateral premium.

conducted from condition

LHS downward

(kn/kt) will shift the

LHS

a

First,

(3).

down, leading to a decrease in

rise in

so that

prices.

number

of comparative statics can be

the ratio of N-production to T-production

P

falls.

Second, a

fall in

6n also shifts the

Finally, a rise in 6t will cause the supply of

26

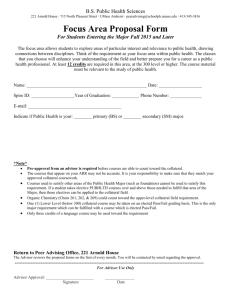

Figure 1 illustrates shifts on

T-shares to shift inward resulting also in a decrease in P.

LHS

(upward sloping curves) and

investment and prices in the

The main consequences

RHS

fire sale

(vertical lines), together with their consequences for

region.

of negative aggregate shocks, in terms of moving the

into or along the fire sale region, are well captured

economies as their St increases. This

decreasing curve of

economy has

Thus, in the

less

what we do

and

cross sectional comparison of

in figure 2.

Raising 6t traces out a

Additionally, a large 6t will

in the fire sale region.

less international collateral

This will lead to

e).

P

is

by the

is less

economy

able to fund

its

mean

that the

shock in the N-sector.

production of N-goods at date 2 and an appreciating currency (lower

fire sale

region

eP

is

uniformly downward sloping.

In the wasted collateral region, domestic firms that do not receive a shock hold both

The return on N-shares

N-shares and T-shares.

eRt. Since firms are holding both

Rn/P

is

N and T shares,

while the return on T-shares

is

arbitrage will dictate that,

Rn/P = eRt

26

Note that an increase

in

by the productivity growth

Rt lowers

P but by less than the increase in the former.

in tradeables, the relative price

17

of N-shares

rises.

That

is,

once correced

I./K&

Figure

Equilibrium in the Fire Sale Region

1:

or,

The

first

region of this graph

is

enough that the only constraint that

and there

is

wasted international

sufficient T-shares.

The second

the case in which

t

6 FS .

<

limits investment is the

In this case 6

region

is

where, 6t

insufficiency of international collateral leads

>

.

both to a

small

domestic collateral constraint

collateral. Prices in this region are

6 FS In

is

simply

this case

fire sale

eP

P since there

falls

is

because the

and an appreciated currency.

Then, the collateral premium,

eP

which

is

6t

clearly increasing in

.

As the

collateral

premium

rises,

the cost of financing

production in the N-sector becomes higher as issuance and sales of N-shares occurs at

sale prices.

is

The

collateral

premium

is

fire

financed with the surplus from reinvestment, which

gradually transferred to T-shareholders. There

is

a point where

this transfer is complete,

and from then on firms bit by shocks withdraw voluntarily as they prefer to cut reinvestment

rather than "give away"

all

their N-shares at

region of the diagram, where &t

Returns and transfers.

2 both domestic

and

>

extreme

fire-sale prices; this is

Q IC , snd can be shown that

the right-most

P = 1/Rt-

In Region 1 only the domestic constraint

is

binding, while in region

international constraints bind. In region 3 only the latter constraint

18

\\

\

\

X

"\^

e/R,

^

1

6K

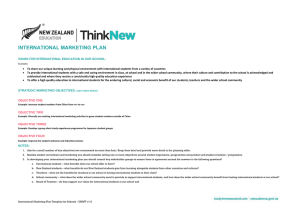

Figure

binds. This observation

which ones do not, and

is

2:

Regions

important for understanding which arbitrage relations apply and

will play

a key

role later

on when we analyze the

social inefficiencies

associated to each region.

The

sells

is

return to purchasing N-shares to an outside investor depends

one share on the T-sector which

is

Thus, the external return on investment at date 1

ext

P.

The

investor

a claim on T-goods at date 2 totalling Rt. This

used to purchase 1/P units of N-shares which each return

r

on

Rn

units of date 2 N-goods.

is,

= Rn = L,

PeRt

while the social or total return

is

r

tot

= Rn

L

L

e

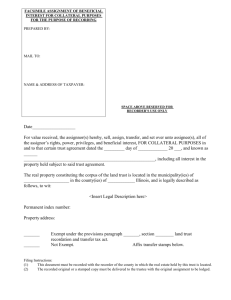

Figure 3 depicts these returns as a function of 0*

L —

1,

the external return of T-shareholders

capital. Collateral providers,

is

.

In the wasted collateral region,

equal to one, the international cost of

which are in excess supply in equilibrium, bid up

P in their

attempt to capture part of the surplus of reinvesting in a constrained firm. In equilibrium,

all

the surplus goes to the constrained firms.

supply shortage of international

collateral.

19

The problem

is

one of demand rather than

eR

a*

Figure

In the

since

all

and

in so doing bid

the collateral premium, L, above

1.

collateral

becomes binding

Constrained firms compete for the few units of

the pledgeable shares are used.

international collateral,

Returns

on the other hand, the supply of

region,

fire sale

3:

e,

As

down the

this

relative price of N-shares,

and

raise

happens, the domestic collateral constraint

becomes binding, hmiting the amount of surplus that constrained firms can transfer to

collateral providers.

Eventually, as the increase in

t

keeps reducing the amount of pledgeable T-shares,

reach a point where the entire surplus

is

transferred to external investors (region 3); from

then on the price of N-shares stabilizes at

2.3

Fire Sales

P = 1/Rt, which sets r^ = r*°*.

1

and the Banking System

Domestic financial systems play many useful

collateral.

we

Most of these

roles

functioning stock markets.

roles in the allocation

we have already circumvented

One we have

not, however,

is

and aggregation of

in our assumption of perfectly

the capacity of banks to

smooth

the distinction between domestic and international collateral in the eyes of foreign investors.

In emerging economies, banks are largely in the business of intermediating foreign funds

into nontradeable sectors.

In our setup, since the tradeable sector has direct access to

international financiers, banks have

an "arbitrage" opportunity

20

in the

nontradeable sector

and naturally borrow abroad to lend to

This intermediation

this sector.

when domestic

is

highly beneficial,

especially in the event of

a

crisis,

of future T-shares which

is

not part of international collateral due to governance problems

in that sector.

a

However, the cost of this activity

-

fragile capital structure

and

collateral

T-liabilities).

A fire

and

assets

is

that

it

leaves the

banking system with

that are de-facto mismatched (N-assets

liabilities

sale in this context will deteriorate banks' balance sheets rapidly

by lowering the value of assets (N shares) while leaving the

create a host of problems

can be used to access that part

by

itself,

either

or simply through the possibility of a

substantial withdrawal at

due to

unchanged. This can

rigid institutional factors

bank run by

fire sale prices

liabilities

foreign investors

(BIS constraints)

which

would dry up the banks resources.

adequacy

the reason for the failure of the banking system

is

straightforward but important recommendation

that closing banks using

as a reference is not a

good

is

amounts to a

idea. It

reduce international collateral at the wrong time.

rigid capital

self inflicted

realize that

27 ' 28

Indeed

ratios,

a

if

a very

fire sales prices

bank run, which can

in turn

29

Foreign Leverage

2.4

Opening the

capital account at date

domestic firms to increase their scale of

will allow

production by selling some of their T-collateral to foreigners and using these proceeds to

finance

have

more production. At the aggregate

level,

less T-collateral to sell to foreigners at

aggravate the price decline in the

We shall

analyze

how

fire sale

date

the consequence of this

1.

We

show

is

that firms will

in this section that this will

region.

equilibrium relation, (3), in the

4

,

u..d\-

l

fire sale

region,

~Pi

changes with the introduction of foreign leverage.

Changes

in foreign leverage

First, if firms sell

have

effects

on both the

reversal in cross-board interbank lending,

Most of the

and

LHS

a fraction Of of their T-shares to foreigners at date

"See, for example, Diamond and Dybvig (1983)

28

Indeed, the bulk of the capital flows reversal in the

in 1997.

RHS

pre-crisis loans

crisis

of this expression.

0,

the

RHS

of this

economies of Asia came in the form of a sharp

which went from 41

billion dollars in

1996 to minus 32

billions

were transformed into unhedged domestic currency loans or foreign-

denominated loans to the N-sector (primarily

real estate), in

which case exchange-rate risk came in the form

of credit risk. Banks' realization of the risky nature of their unhedged positions after Thailand's devaluation

was a big factor behind the regional currency crises that followed; see IMF (1998).

29

As for real or self inflicted bank runs, they can be avoided by boosting the price of N-shares. In a

multiple equilibria scenario, this can be done by just credibly announcing a transfer to "patient" foreign

investors in the event of a run.

As

always,

if

credible this policy will cost nothing.

21

expression will become,

l—^ktil-Ot-Of)

P

Selling shares at date

to date

1.

The per

cjf , falls since

also reduces holdings of T-shares as internal collateral

on the distressed entrepreneur's holdings of T-shares,

capital return

a fraction of

from date

this is sold to foreigner. Thus,

u;?

= (i-p)(i-e -ef

,

t

)

Substituting these into the equilibrium relation yields,

i-(i-en )PR

(knPu}»

+ ** (1 ~ 6t ~

t

The key

expression to be analyzed

is

kt(l

W = ^y-

—

9t

— 6f). On

from foreigners allows financing more production, so that

increased production

is

- 0t ~ W-

the one hand, raising funds

kt rises.

On

the other hand, this

held mostly as illiquid shares by domestic firms so that they hold

of the fraction of aggregate collateral at date

less

h{l

shares issuance are used towards an increase in

1.

Suppose that

all

of the proceeds of

so that collateral creation

A^,

is

maximized.

If

the firm had originally invested k\ in the T-sector, opening the capital account will allow

it

to scale this investment

up

to,

kt

i-R (i-p)ef

t

Then,

d

89f

The numerator must be

i-e -ef

t

1 - R

less

t

l- (i e )Rt(i

1 - Rt(l - p)9f

t

(l - p)9f

than zero or production

reflecting

P must fall.

resulting in

down

would be a money

— 9t — 9f)

falls

with a rising

First, the vertical curve shifts to

a contraction in the aggregate supply of collateral at date

curve for T-shares shifts

that

two ways.

<

in the T-sector

machine (which we must rule out by assumption). Since kt(l

9f, the curves in figure 1 are affected in

p)

reflecting the fall in

domestic

1.

Second, the

collateral.

The

the

left

demand

net of these

is

Thus, aggregate collateral in the economy declines with foreign leverage

a steeper price decline in the

fire sale

region.

A puzzling feature of crises is that both flows and stocks, rather than only stocks, seem

to contribute to their unraveling

and

likelihood.

Our model

offers

one possible explanation.

Flows matter primarily through distressed firms which in principle can renegotiate the

stock of debt but need the

new

flows to survive.

Stocks,

on the other hand, primarily

matter though sound firms, by curtailing their role as suppliers of international collateral.

22

The

3

Pre-Crisis Phase

The Model

3.1

Introduction.

in

Of

advance of the

course,

many

crisis itself.

of the conditions that lead to a crisis are created well

The

analysis thus far has taken these initial conditions as

given and illustrated the types of problems that they might lead

international collateral

question that arises

is

is

what

largely

why

to.

As a shortage

of

responsible for triggering a fire sale, a natural

is

the private sector does not anticipate this and take steps to

invest in highly profitable international collateral. In order to address these issues in our

model, we add a history to our economy; a date

in

which agents have

full flexibility.

In particular this section addresses two sets of choices: production and financing.

On

the

production side, we study the difference between private and social incentives to allocate

benefits

and

On

and nontradeables.

factors of production to tradeables

costs of foreign leverage that results

the financing side,

we study

the

from opening the capital account at date

0.

The

must

Firms at date

basic problem.

first

how much

decide

N- and T-sectors. Production requires resources at date

finance this production

— how many T- and N-shares

the complement of this financing decision

to produce in each of the

and firms must decide on how to

to issue against production. Finally,

an investment decision

is

— how many T- and

N-shares of other firms in the economy should be purchased.

We focus

first

on the case in which there

total resources of the

economy are

fixed,

kn

is

no date

we must have

borrowing from abroad. Since the

that,

+ kt = w.

While the incidence of crises must surely by tied to aggregate shocks, our model allows

us to highlight the main issues leading to a

crisis in

an environment with only idiosyncratic

shocks. Given wealth at date 2 (in units of N-good) of t«2, a firm solves

—

Since uncertainty

is

-1 ' 2

= max{tzd

idiosyncratic, e

is

s.t.

Cte

deterministic

+ Cn= W2-}