Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/educationincomedOObena

HB31

.M415

Dew e y

€>

/ <P

working paper

department

of economics

EDUCATION, INCOME DISTRIBUTION, AND GROWTH:

THE LOCAL CONNECTION

Roland Benabou

MIT

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass. 02139

EDUCATION, INCOME DISTRIBUTION, AND GROWTH:

THE LOCAL CONNECTION

Roland Benabou

MIT

94-16

May 1994

M.I.T.

LIBRARIES

JUL 1

2 1994

RECEIVED

Education, Income Distribution, and Growth:

The Local Connection

Roland Benabou

MIT

September 1993

Revised

am

May

1994

Diamond, Dick Eckaus, Jonathan Gruber,

Michael Kremer, Glenn Loury, Julio Rotemberg, Richard Startz and Jean Tirole for useful comments.

Financial support from the NSF is gratefully acknowledged.

I

grateful to Olivier Blanchard, Patrick Bolton, Peter

Abstract

This paper develops a simple model of human capital accumulation and community formation by heterogeneous families, which provides an integrated framework for analyzing the local determinants of inequality

and growth. Five main conclusions emerge.

First,

minor differences

or wealth can lead to a high degree of stratification.

will

compound

Imperfect capital markets are not necessary, but

these other sources. Second, stratification

persistent across generations.

Whether

or not the

in education technologies, preferences,

same

makes inequality

is

in

education and income more

true of inequality in total wealth depends on

the ability of the rich to appropriate the rents created by their secession. Third, the polarization of urban

areas resulting from individual residential decisions can be quite inefficient, both from the point of view of

aggregate growth and in the Pareto sense, especially in the long run. Fourth,

of school expenditures

poor communities

is

much

and income growth both

and

efficiency. Fifth,

insufficient to

less

than

fall.

it

Yet

reduce stratification,

lowers

it

may

it

in richer

still

it

when state-wide

may improve

educational achievement in

communities; thus average academic performance

be possible for education policy to improve both equity

because of the cumulative nature of the stratification process,

harder to reverse once

it

has run

its

equalization

course than to arrest at an early stage.

it is

likely to

be much

Education, Income Distribution, and Growth:

The Local Connection

by Roland Benabou

Abstract

This paper develops a simple model of

human

capital accumulation

and community formation by

heterogeneous families, which provides an integrated framework for analyzing the local determinants of

inequality and growth. Five

main conclusions emerge.

First,

minor differences

in education technologies,

preferences, or wealth can lead to a high degree of stratification. Imperfect capital

essary,

but

will

compound

these other sources. Second, stratification

income more persistent across generations. Whether the same

on the

ability of the rich to appropriate the rents created

by

is

makes

markets are not nec-

inequality in education and

true of inequality in total wealth depends

their secession. Third, the polarization of urban

areas resulting from individual residential decisions can be quite inefficient, both from the point of view of

aggregate growth and in the Pareto sense, especially in the long run. Fourth,

of school expenditures

poor communities

insufficient to reduce stratification,

is

much

less

and income growth both

and

efficiency. Fifth,

than

fall.

it

Yet

lowers

it

may

it

in richer

still

it

when

may improve

state-wide equalization

educational achievement in

communities; thus average academic performance

be possible for education policy to improve both equity

because of the cumulative nature of the stratification process,

harder to reverse once

it

has run

its

course than to arrest at an early stage.

it is

likely to

be much

Introduction

The accumulation

growth.

of

human

As demonstrated most

vividly

by the physical blight and

certain fundamental inputs in this process are of a local nature.

level of individual families

decentralized, but also with

Not only

many forms

They

are determined neither at the

is

this the case with school resources

fiscal

determined in large part by the set of adults to which she

and incomes

is

directly

when funding

of "social capital": peer effects, role models, job contacts,

norms of behavior, crime, and so on. Through these

distribution of skills

social pathology of inner-city schools,

nor that of the whole economy, but at the intermediate level of communities,

neighborhoods, firms or social networks.

is

income inequality and productivity

capital underlies the evolution of both

and sociological

is

spillovers,

a

child's education

is

"connected". Therefore, the next generation's

shaped by the manner

in

which today's population organizes

itself into differentiated clusters.

The aim

of this paper

is

twofold.

First, to

provide a unified analysis of the forces that

socioeconomic segregation, income distribution, and productivity growth.

We

tie

together

develop a simple model

where heterogeneous families form communities, choose local public expenditures, and accumulate human

capital. It allows us to elucidate the roles played

by endowments, preferences, the technology of education,

capital markets, school funding, neighborhood effects,

us to incorporate

The second

some of the main

objective of this paper

insights

is

and discrimination.

from the previous

on the transmission of inequality across generations;

of inner-city poverty,

and on

we examine some

The other

new

two important questions. One

effect of stratification

policy:

synthetic quality also enables

literature, while obtaining several

to further our understanding of

social mobility in general.

Its

it

ones.

is

the

bears directly on the problem

central issue concerns education finance

of the distributional and aggregate implications of the growing trend towards

court-mandated, state-wide equalization of school expenditures.

The

literature to

which the paper belongs has

its

sources in the classic works of Tiebout (1956) on

local public

goods and Schelling (1978) on segregation and externalities. More recent prominent influences

include the

work of Loury (1977), (1987) on

racial inequality

and of sociologists such as Coleman (1988),

Wilson (1987) and Jencks and Mayer (1990) on group interactions. Another important motivation

current debate over local disparities in school funding, perhaps best publicized by Kozol (1991).

developed here builds on

De Bartolome

(1990),

Benabou

(1993), (1992)

is

the

The model

and Durlauf (1992). But the paper

is

also closely related to Borjas (1992a), (1992b), Durlauf (1993),

(1993), through the link between

Tamura

community composition and the

(1993) and Lundberg and Startz

persistence of inequality;

and to

Glomm

and Ravikumar (1992), Fernandez and Rogerson (1992), (1993b) and Cooper (1992), through the issue of

education finance reform.

We now

outline the structure of the paper

In Section 2,

we

identify the forces which

show how even very small

and

its

main

The model

results.

is

presented in Section

promote or hinder segregation and explain

The

differences in education technologies, preferences or wealth lead to a high degree

rest of the

on productivity, we examine

compound

the

paper studies the potentially large effects of these small causes. Focusing first

in Section 3

how

the total surplus generated by a metropolitan area reflects

organization into local communities. In particular,

its

We

their interactions.

of stratification. Capital market imperfections are not necessary, but even minor ones will

other factors.

1.

we

explain

why

the typical pattern of city-suburb

polarization can be very inefficient.

We

We

then take up the issue of whether socio-economic segregation makes inequality more persistent.

demonstrate

the long run this

in Section 4

may

how income convergence

reduce income growth for

is

slowed down, how ghettos

all families.

We

arise,

and how

in

present in particular a very simple

prototype of the "local poverty trap" and "self-defeating secession" phenomena, which makes apparent the

general principles at work in more complex models

(e.g.,

Benabou (1993), Durlauf (1992),

because our framework allows for financial bequests as well as

human

capital,

we

(1993)).

But

are also able to point

out an important qualification which the previous literature has generally overlooked. While stratification

exacerbates inequality in education and income, the same need not be true for inequality in total wealth.

The determinant factor

is

the cost paid by the rich to separate themselves from the poor, or conversely the

extent to which they are able to appropriate the rents generated in the process of segregation.

various collective practices and institutions by which this

may come

We discuss

about, showing in particular

how

it

jure racial segregation turns into de facto (economic) segregation once legal barriers to mobility are lifted.

The other main

issue studied in the

tralization of school funding

it

paper

is

education finance.

We show

in Section 5 that the decen-

and control constitutes an additional segregating

force,

and that

in general

need not improve efficiency In Section 6 we then examine the implications of policies, adopted by a

growing number of states, aimed at reducing disparities in education expenditures between rich and poor

communities. Benabou (1992) and Fernandez and Rogerson (1993b) predict very significant gains to moving from a system where school funding

is

based on local resources to a national or state-wide scheme. In

addition to reducing inequality, this would raise the economy's long-term output, or even growth rate; given

a low enough intergenerational discount rate,

it

would be Pareto-improving. In

this

paper we temper this

optimistic scenario by downplaying capital market imperfections, and emphasize instead the interaction

between purchased inputs and

cast doubt

on the effectiveness of redistributive funding

in reducing earnings inequality

Indeed, several pieces of evidence seem to

social spillovers in education.

in raising the

and augmenting aggregate surplus.

We

model can help explain some of these puzzles.

performance of poor schools, hence

We

show how a simple version

determine when equalization works and when

counterproductive, and, in the latter case, identify alternative policies which

and

efficiency.

of our

Because these policies work through changes

may still

it is

improve both equity

community composition, however, they may

in

be constrained by a form of irreversibility which we show to be inherent in the stratification process.

We

conclude this preamble with some suggestive evidence on metropolitan stratification and growth.

While the

neighborhood and school composition on individual outcomes have been extensively

effects of

documented, there

is

as yet

no empirical study of

provocative data which bears on the issue; since

for the

their aggregate implications.

it is

very incomplete,

paper rather than supporting evidence for specific

areas, selected

by Rusk; the data

is

also plotted in Figure

results.

1. It

we

Table

1

Rusk (1993) presents some

include

are respectively .74

as

Rusk

and

.91,

income (1969-1989) and

shows a strong positive relationship between

total

may

mean incomes, and

employment (1973-1988). The

or .60 and .45, depending on whether

does, or in 1970, which

as general motivation

examines fourteen metropolitan

the lack of economic segregation, measured by the ratio of central city to suburban

area's growth in both per capita

it

we measure income

be more appropriate. 1 This striking stylized fact

the

correlations

disparities in 1989,

is

no substitute

a systematic econometric analysis, and does not allow any inference about causality. But

it

for

does suggest

that city-suburb stratification and metropolitan economic performance are interdependent processes, and

that the underlying

mechanisms deserve

careful theoretical

and empirical investigation.

'I am grateful to Ed Glaeser for kindly providing the 1970 figures, from the Census Bureau's County and City

Data Books. The above result seems opposite to that of Glaeser, Scheinkman and Shleifer (1993), who find that

racial segregation in a city affects population growth positively. Note, however, that the focus is here on city-suburb

economic dichotomy, rather than on racial segregation and population growth within city limits.

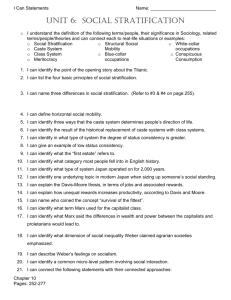

Metro per capita income

growth (%)

Metro employment

growth (%)

1969-1989

1973-1988

23

8

53

26

11

83

81

34

40

Milwaukee, Wis.

84

62

25

22

Harrisburg, Pa.

87

72

33

29

Louisville, Ky.

91

79

30

21

Richmond, Va.

91

83

45

46

Nashville, Tenn.

92

98

49

55

Syracuse, N.Y.

98

77

29

27

Madison, Wis.

104

95

34

51

Houston, Tex.

107

89

36

67

Indianapolis, Ind.

108

90

32

34

Raleigh, N.C.

119

103

62

81

Albuquerque, N. Mex.

148

118

41

75

Metro Area

City/Suburb per capita

income ratio (%)

1989

1970

Cleveland, Ohio

69

53

Detroit, Mich.

80

Columbus, Ohio

Table

1:

City-Suburb Inequality and Metropolitan Area Performance.

Source: see

Rusk

(1993),

and footnote

1

flfura la

Flgnra lb

a

a

a

79

100

U5

TBATI089

Flfun

lc

Flfur* Id

TEATI070

TRATI070

2.5

3.0

s

a

>•

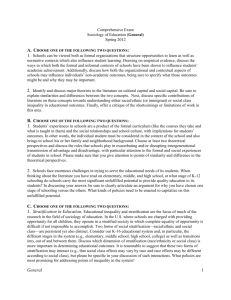

City-Suburb Inequality and Metropolitan Area Performance

YRATIO= relative city /suburb mean income; YGROWTH=annual growth rate of metropolitan income

per capita; NGROWTH= annual growth rate of metropolitan employment. All values are percentages

Figure

1:

The model

1

1.1

Agents and communities

There

is

a continuum of families, with unit measure. Parents are of two types,

White and Black,

n and

city

1

—

n.

etc.),

human

with

The average

level of

capital

human

A

and

B

capital

is

=

j

denoted h

=

n h&

+ (1 — n) /»b-

1,2, each holding the

These agents

from

All land belongs to absentee landowners; departures

as the richer one: x 1

> In —

A

x2

.

In the

with two types and two communities

associate in the provision of formal

of a city with

many

populations; almost

assumption that

1.2

A

maximize the resulting

denoted as i J and community

1 is

,

would be the

is

the minimal framework in which to study

and informal education.

— hB)/h

is

denned

we

It

reverse.

how

agents

can also be viewed as a representative

"slice"

focus on any pair of contiguous towns and their

small.

parent with type h €

utility

c

first

period, she

=

amount borrowed

+ p>+V{h)

= u (h) +

c',

C1

,

j

=

1,2, so as

y(h)

h'

=

F{h,ti,E>)

c

and pays rent

debt

d.

The

(P

h')

,

subject to

d

=

level of

or saved.

max<i U(c,

d + P{h,d)

consumes

augmented by her chosen

chooses a community

{/lyt./ifi} initially

U^(h):

U' (h)

In the

is

Preferences and technologies

There are two periods.

to

(h A

not essential.

extend to such a model. Thus we shall occasionally make the convenient

results

Ah/h =

is

it

types and communities, where

all

a

American context the two locations would be referred to as

"the suburbs" and "the urban center"; in Europe

A model

live in

this neutral allocation are considered later on.

agents in each community

=

i1

are

same number 1/2 of single-family

homes. The inelasticity of land supply and population density simplifies the analysis but

of rich, or type

and poor,

endowments h* > ha- The proportions of the two types

composed of two towns or communities,

The proportion

(rich

plus taxes t'(h) out of her initial resources w(A),

interest rate r(h,d)

In the second period, the resources

may depend on

d available

for

her type as well as the

consumption or bequest

(both interpretations are possible) equal second period income y(h), minus debt repayments P(h,d)

+ r(h,d)).

d(l

Finally, the child's

education), by the quality

to

its

schools,

The

V

local spillover

by the

affected

capital h'

is

determined by that of the parent (through at-home

of social interactions in the chosen community, and by the resources devoted

measured by the per student budget E* ?

Neighborhood

1.3

V

human

=

social

effects

captures the non-fiscal channels through which a child's acquisition of

mix of neighboring families. These sources

Coleman

of "social capital" (Loury (1977),

(1988)) include: peer effects between students from different backgrounds, both in

skills is

and out of the classroom

(Banerjee and Besley (1991)); the fact that neighboring adults enforce norms of behavior and provide role

models, as well as networking contacts, for the young (Wilson (1987), Streufert (1991), Montgomery (1991));

and crime or other

V

that

=

adults in

L(x J h A ,h,B)

;

C

J

(in the sense

and

activities

is

homogeneous of degree one

share the same level h, then

V

—

We

h.

D

of

L

also require

human

Another key feature of the

how

beneficial

is

spillover

L

=

capital,

>

human

0,

the

CES

it is

complements, L

is

=

if all

with h A

capital; its value for a

L(n; h A hs),

How

heterogeneity within a school or neighborhood? Put in another way, do stronger

(x h A '

convex

rises

response to a mean-preserving spread in the distribution.

is its

A

important to allow both cases. 4

index L(x)

and that

and L

individuals tend to "pull up" the average to their level, or do weaker ones tend to "drag

Clearly,

we assume

any improvement

to increase with

as an average of local residents' levels of

representative sample of population will be denoted

costly, or

in the distribution of

loss of generality,

of first-order stochastic dominance) in the local distribution: L'(x)

One can thus think

/ifi.

which disrupt education (Sah (1991)). 3 Without

+ (1 — i) h B

in i,

'

convenient specification which

)'-»

and heterogeneity

.

When

is

1/e

>

a source of

0,

we

it

shall

individual levels of

loss:

L <

h.

When

down"

to theirs?

sometimes use

is

human

capital are

<

individual

1/e

0,

2

More generally, F(h,L,E) should be understood as the child's earnings potential, net of her optimally chosen

studying effort (measured in the numeraire good). Incorporating private purchases of education is also straightforward: c and E are replaced in (1) by c + e and E + e, and parents maximize over both e and d.

3

Jencks and Mayer (1990) provide an extensive survey of the empirical evidence on neighborhood effects, and

Manski (1993) a discussion of methodology. Recent studies include Datcher (1982), Dynarski et al. (1989), Corcoran

(1990), Crane (1991), Borjas (1992a), (1992b), Case and Katz (1991), and Brooks-Gunn et al. (1993).

Dynarski, Schwab and Zampelli (1989) find that average student performance in a school district rises, ceteris

paribus, with dispersion among family incomes. Hamilton and Macauley (1991), on the other hand, find that

income dispersion raises the unit cost of education. Brooks-Gunn et al. (1993) find that it is primarily the upper

et

al.

4

tail

of a neighborhood's

income distribution which

affects the

development of children and adolescents raised

there.

i

levels are substitutes,

L

is

concave in x, and heterogeneity

(minimum) and "best-shot" (maximum)

generally, the concavity of L(x) will be

1.4

Local school funding

The

other local input into education

and poor agents

of rich

is

a source of gains: L

>

cases are obtained in the limit as 1/e goes to

h.

+00

The

Leontieff

More

or —00.

an important determinant of the efficiency of equilibrium. 5

decentralized school expenditures. 6 Given the distribution (z J

community -hence, given

in the

is

social capital

D

and rents p>-

,

1—

J

)

their preferences

over school budgets and taxation are aggregated by some local political mechanism into funding decisions

& = E(x

3

)

and tax schedules V{h,p)

x')t{hB,f>i ,xi)

political

=

E(xi).

mechanism

1

+ (l —

The

be majority voting, the outcome of lobbying, or delegation to an

moment we

For the

mechanisms which promote

t(h,p,x'), subject to the budget constraint i J t(hA,p' a^)

thus allow taxes to depend on individual income and property values. 7

in question could

efficient local planner.

of

We

=

shall leave

it

unspecified, so as to identify the general features

or hinder segregation.

Equilibrium

1.5

Let us rewrite the utility of an adult of type h, living in a community with percentage x of rich households

and paying p

in land rent, as:

V(h,p,x)

=

max{U(u,(h)

+ d-p-t(h,p,x),y(h)-P(h,d),F(h,L(x),E(x))}

(2)

a

Equilibrium in the land market

to bid

more than the poor

will result in stratification if the rich (in

for land in a richer

community. Formally,

human

capital) are willing or able

this simple sorting condition in the

space of community quality and price means that a rich family's iso-utility curve, or bid-rent,

5

For a more detailed discussion, see Benabou (1992). Similar functional forms are used by

studying the provision of public goods with non-additive individual contributions.

As

for social composition, the link

Comes

is

steeper

(1993) in

between expenditures and students' achievement or future earnings

is

the

much

empirical debate. See Hanushek (1986) and Card and Krueger (1992) for opposing views.

Note that the 3 and t J (h, p) chosen by 3 residents may depend on the equilibrium rent p3 (as opposed to an

subject of

E

C

individual's bid p), through its effects on their wealth

To keep

the notation simple, this dependence on j

is

and on potential revenues from alternative forms of taxation.

in the dependence on x 3

subsumed

.

than a poor one's:

V*(h,p,z)

J?,(A,p,x)sg

—VP (h,p,x)

v(h,p',z')=v(h,p,x)

increases with h

1

In that case, the slightest divergence from the symmetric allocation x

equilibrium) in favor of

for land in

C

community

1

will set in

motion a cumulative process:

thereby further raising x 1 ,/? 1 and lowering x 2 ,p2

1

,

poor by the rich in

C

1

=

and more concentration of poverty

in

C2

,

.

x2

=

(3)

n (which

is

always an

rich agents outbid

poor ones

This leads to more displacements of the

until at least

homogeneous. The three possible configurations are indicated on Figure

1,

one community

is

completely

together with the equilibrium

s

conditions on p 1 and p 2

.

Rh x {h,p,x) >

Proposition 1

1.

If

the rich all live

m

communtty

1,

— In—

x2

2.

it is

If

1).

for

all

umque

p,x, the

2n, x 2

—

0); if

The symmetric equilibrium x 1

=

x2

Rhz(h,p,x)

<

for

1

all

(i 1

=

=

>

n

n

stable equilibrium, is stratified.

1/2, the poor all live in

n

<

1/2,

community 2 (x 1

=

unstable.

is

p,x, the unique equilibrium

is

completely integrated

(i.e.

symmetric), and

stable.

The proof

is

given in appendix.

Examining the marginal rate of substitution between

consumption and child education thus brings to

light the

economic forces which lead to

integration. Using the Euler equation for the optimal level of borrowing,

_

Equation

goods.

8

If

(

U3 {c,c>,h>)

FL

-L'(x)

+ FE

-E'(x)

will

stratification or

we have:

m \\

n .i( h

(4) incorporates the contributions of technology, preferences, capital

The corresponding components

first-period

n r \\-i

U)

markets and local public

be discussed in turn.

As in much of the literature on community composition (e.g., De Bartolome (1990), Wheaton (1993)) we only

determine the rent differential which ensures that no agent wants to switch communities. The base level of these

rents could be pinned down by relaxing one of the simplifying assumptions of inelastic land supply and fixed number

of agents of each type, but this would needlessly complicate the model.

CD

m

o

o

n

||fi>||

CD

3

ii

<

«•—»

A

_

v.

ro

CD

OD

~t>

ro

«

>

QD

"o

-

«

X

X

2]

Q

c

JO

m

ro

O

a

(A

I

1

<

3"

>

<

y

CD

x

ro

ro

X

ro

«_«

«»^

IV

IA

O

O

x__

ii

<

ro

x

ro

:KSK:>x;S;i;iS

ii

\

ro

~0

ro

«

3

GD

The determinants

2

Local complementarities

2.1

simplest version of the model

The

F=

quality,

d(l

of stratification

+ r);

so that

is

that where: (a) the only local input into education

is

community

F(h, L), so that no collective decisions are involved; 9 (b) capital markets are perfect, P(h, d)

(c) utility is linear,

U3/U2

bid-rent slope

is

U(c,d,h')

= c + (d + /»')/ (1 + r)

or

more generally d and

when d

constant. This last assumption seems especially appropriate

now

h' enter additively,

is

a bequest. The

simplifies to:

Rxi h,p,x)

Stratification occurs

those with lower

,

=

if

families with higher

human

wealth. In the words of

"The individual's remedy

Those who leave the

who maintain

human

intensifies the

= ^^-L'(x)

1 + r

capital are

Baumol

sensitive to

neighborhood quality than

(1967):

community's problems and each feeds upon the other.

city are usually the very persons

the houses,

more

(5)

who do not commit

who

care and can afford to care-the ones

crimes, and

who

are most capable of providing

the taxes needed to arrest the process of urban decay. Their exodus therefore leads to further

deterioration in urban conditions and so induces yet another

wave of emigration, and so on."

Proposition 2 A small amount of complementarity between family human

(FhL

>

0)

is

sufficient to cause stratification.

capital

The distribution of financial wealth

and community

is

quality

irrelevant.

This simplest specification of preferences and technologies will be referred to as the "basic model"

contrast to most of the literature on inequality,

it

shows that there might be very

policies to affect either the distribution of educational

9

little

.

In

role for redistributive

attainment or the efficiency of equilibrium.

is that agents care about community

impact on their child's education; crime is a good example, with richer agents

caring most about it. The second is that F = F(h, E) and communities finance schools by taxing income at a fixed

rate (such is then case when preferences are logarithmic; Glomm and Ravikumar (1992)). Then E(x) = r* L(x),

where L(x) 5 tw(^) + (1 — x) u»(fes) is simply average income in period 1.

This model also admits two interesting alternative interpretations. One

quality

L

for reasons other

than

its

8

Capital market imperfections

2.2

In reality,

it

may not

be easy for a poor family

We now show that differences in

well-educated community.

rich,

who values education

"ability" to

pay

to complement, or even replace, differences in "willingness" to

We

Proposition 3 Small imperfections

poor families (Phd

The

in generating

in capital markets, resulting in a higher opportunity cost of funds for

monitoring technologies, or a tax subsidy to

when only

A

families can afford a

The

=

with increasing marginal cost of borrowing (or decreasing marginal return on savings)

P" >

0,

>

0;

is

rich ones:

0.

10

earning

in their first period of life,

In order to live in the

same community,

d decreases with h for any given

A

agents are always lenders and

p,

less

wealthy

hence the

result.

B

agents always borrowers

<

Alternatively, the imperfection could take the form of a borrowing constraint, d

resources are such that

it

binds for the B's but not for the

former but an equality for the

latter,

implying again

j4's,

the Euler condition

is

Rx (h A ,p,x) > Rx (hB,p,x).

repeating that, absent offsetting forces, segregation will occur no matter

credit

same

that of a wedge between borrowing and lending rates, as in Galor and Zeira (1993);

endowments which ensure that

are easily found.

=

during retirement, y(h)

must then borrow more than

conditions on

for the

relative to

downpayment.

to endogenize this differential. Let everyone face the

is

simplest case

When

home ownership

P(d)

way

with u)'(h)

families

F(L), and

F'(L) L'(x) / Pd(h,d).

due to standard asymmetric information problems. Let agents work only

wj(/i),

— \,F =

interest schedule

better

+ r(d)),

U3/U2

0) are sufficient to cause stratification.

reflect different

renting (interest deductions),

A

<

d'ihjPjj

economic segregation. 10

most simply when each family faces a constant opportunity cost of funds, with r^ < tb

result arises

This could

in (5).

+

=

move into a

pay for community quality tend

abstract from inter-family differences in tastes or returns to education,

allow instead frictions in credit markets: Rx(h,d)

d(l

highly to borrow enough to

how small wealth

d.

an inequality

But

it

bears

differences

and

market imperfections.

The

empirical literature yields contradictory estimates of the sign of Fhl\ see Jencks and

most recent study (Brooks-Gunn

et al. (1993)) finds

Fhl >

9

0.

Mayer

(1990).

The

Wealth

2.3

We now

effects

focus on the term (Ua/U2)(c,c',h') in (4), which captures preferences for education relative to

To

old age consumption or financial bequest.

isolate

wealth

perfect. Finally, let parental utility be additively separable: U(c, d, h')

p h

^

(

„ ,->

(/l,p

x)

where u(z)

= max, {u(z -

Proposition 4 Small

s)

'

=

F(L) and

u(c)

capital markets be

+ v{d) + w(h').

Then:

- W '( F L )) F(L)L

V - W 'W L » F

F'(L\

V

{L) L

- -vgy F>(L\

u'(z(h)- P)

(

+ v(s(l + r))}

differences

F=

effects, let

m

and z(h)

= u(h) + y(h)/(l + r)

lifetime resources (w'(/i)

+y

/

(/»)/(l

is

lifetime wealth.

+ r) >

0) are sufficient to cause

stratification.

When F =

cation occurs

less

if

F{h,L), the marginal rate of substitution

This

is

U3/U2 = w'(F(h,L)) /u'(z(h) -

in the

marginal

the sense in which

utility of

consumption which

results

different levels or rates of taxation across

communities

(e.g.,

rich agents vote for high taxes to finance public goods,

This leads, through a Tiebout (1956)

good. Similar wealth effects

infinitely elastic-

but through

Femandez-Rogerson (1992)). Ceteris paribus,

such as education, whereas poor ones prefer lower

mechanism, to as much segregation by wealth as the

is

the case in Fershtman and Weiss's (1992) analysis of socio/ status, where agents derive

from being

in

a profession with a high proportion of well educated members. Wealthier agents are

willing to accept

a lower remuneration of human

capital, in

more of them become highly educated, and the labor market

of our

financial wealth

Such

differentials.

more

-like

is

model

We

yield simple versions of

have until now assumed that

exchange

stratifies.

for higher status.

Therefore

We show in appendix how variations

Femandez-Rogerson (1992) and Fershtman and Weiss (1992).

all

land rents accrue to absentee landowners. This

is

a "neutrality"

assumption with respect to the allocation of the capital gains and losses created by stratification

and

is

of communities will allow. Instead of rents or taxes, wages can also play the role of compensating

number

utility

from higher

community composition L must be a normal

underlie models where sorting occurs not through land rents -supply

levels.

p). Stratifi-

the reduction in the marginal utility of education due to better parental background h

than the reduction

z(h).

is

C2

.

It

also simplifies the problem, by

examine how relaxing

this

assumption

making agents'

initial

affects the results. Let

10

wealth exogenous: u(h)

each

A

agent

initially

=

u7(/i).

own vA

in

C

We now

units of land

C

in

T7B

and

1

=

T)

A units

in

C2

;

the corresponding

{l/2-ni) A )/(l-n). Total wealth

endowments

unchanged. The converse, perhaps more

initial allocation

where vA >

— n vA )/(l — n)

= A,B. UuA =

i

,

(1/2

t]

A

=

and

1/2,

=

l/2n,

tj

=

a

0.

More

generally, consider

any

A hence vb < VB- As communities become more concentrated, the wealth

,

Propositions 3 and 4 show that this in itself creates a

when

others are absent.

all

Local public goods, political mechanisms, and discrimination

2.4

mechanism through which communities choose taxes and

defer until Section 5 specifying a particular

But inspection of the corresponding terms

school expenditures.

dency toward

stratification, with a

Proposition 5

FhE >

Political

To

when Fhe < 0) tend

is

to

<

public choice

An

(e.g.,

community (thx{h,p,z) < 0) or with land

0).

which are closer to their preferred choices, stratification

numerous

Tiebout (1956).

produce stratification. So do mechanisms such thai

the extent that a higher proportion of rich agents

all

la

such that expenditures E(x) increase with x when

fall with the proportion of rich agents in the

values (th p (h,p,x)

in (4) already indicates a "natural" ten-

presumption of efficiency gains, a

mechanisms whose outcome

(respectively, decrease

income tax rates

not

1

2

p +T)i p

i/i

=

1/3

another neutral case where the results remain

vA

realistic case, is

segregating force, which can sustain stratification even

We

i

losses; this is

while that of the B's declines.

j4' s rises

of the

r)

agent are

=u(h ) +

levels are w(/».)

both classes share equally in capital gains and

B

for a

mechanisms are such that the

is

will

rich

reflected in taxation

occur as agents "vote with their feet"

become more powerful

majority voting), this requirement seems both fairly weak and

alternative interpretation of th x (h,p, x)

relative to the rich, of joining a rich

<

or thp(h,p,x)

community. These

and expenditure decisions

costs,

<

is

as they

.

Although

become more

realistic.

that the poor incur higher costs,

which are particularly relevant when the

A's and B's correspond to different ethnic groups, can be pecuniary, due to discrimination by owners or

intermediaries in the housing market, or non-pecuniary, such as harassment. 11

when

11

come back

to

them

discussing inequality.

Of

agents

We

course, this

component

who have pure

of

t

does not enter into budget constraints.

"tastes" for the ethnic

mix of

their

community, as

11

Yet another interpretation

in Schelling (1978) or

Miyao

is

that of

(1978).

Stratification

3

and

efficiency: a simple case

We now examine whether it is efficient for different classes of agents to segregate in education. The criterion

we

use

that of aggregate productivity or surplus: are the output gains of rich communities greater or

is

12

smaller than the losses of poor ones? Distributional issues are taken up in Section 4.

exposition,

we

abstract from school funding and taxes; they are incorporated in Section

generated by a community with a fraction x of rich households

= xF{h A

S{x)

,

L(x))

+

is

,

solution

at a corner,

is

+

S(2n

—

and coincides with the

<

stratified

market equilibrium.

< min{2n,

concave, there are decreasing social returns to the concentration of

and symmetric: S'(x)

interior

comparing the gains 5(i 1 )

in the

—

=

S'(2n

—

x), so

=

x

n.

13

The

surplus

(6)

x) over

x

5.

L(x))

A planner choosing population allocations so as to maximize the productivity of the

area would therefore maximize S(x)

simplify the

thus S(x)/2, where:

- x)F(hB

(1

To

If

1}.

human

5

On

is

convex, the optimal

5

is

and the optimum

is

the other hand

capital,

The underlying

whole metropolitan

intuition

is

if

apparent when

S(n) from stratification in the rich community with the losses S(n)

—

5(x 2 )

poor one. To assess the efficiency of equilibrium, we therefore evaluate S":

S'

S"

=

= F(h A ,L)-F(h B ,L) + (xFL (h A ,L) + (l-x)FL {h B ,L))L';

2(FL (h A ,L)-FL (h B ,L))L'

+ (xFLL (h A ,L) + (l-x)FLL (h B ,L))(L') 2

(7)

+(xFL (h A ,L) +

where L

=

an increase

from

in

quality

when

is

The

first

term

community quality?

stratification.

resident,

12

L(x), etc.

in (7) represents the

If

Fm

>

0, it is

from a low or from a high

- x)FL (h B ,L)) L"

answer to the question: who

benefits

most from

the better educated family, hence an efficiency gain

The second term measures whether an

starting

(1

level; if

increase in

Fll <

0,

L

is

more valuable

to the average

the marginal productivity of

decreasing, implying an efficiency loss from stratification.

The

last

term

community

in (7) represents the

how economy-wide complementarities can translate aggregate results into Pareto comand how welfare might differ between the short and long run.

13

Naturally, if 5 changes curvature, the optimum may involve partial segregation.

There, we also explain

parisons,

12

answer to the question: where does a marginal well-educated agent, or family, contribute most to raising

the quality of

it

community?

its

L" <

If

joins than in the poor one which

it

0,

such a family

much

is

less valuable in the rich

leaves behind, leading to another loss

from

In the basic model, agents allocate themselves solely on the basis of the

how small

the private gains which

it

represents. 14

More

community which

stratification.

first

term

generally, wealth constraints

in (7),

no matter

and capital market

imperfections also shape the residential equilibrium.

Proposition 6 Agents

segregate or integrate depending on

factors unrelated to the productivity of education.

Fn

tration effects"

FhL<0, no matter how

The equilibrium can

and on other

small,

be very inefficient, if the "concen-

or L" are large in absolute value and have the opposite sign of Fhh, or more generally

of the incentive to segregate Rhx-

We

shall generally

tration of

be more interested in the case where the city

human wealth on one

side

and poverty on the other

is

stratifies,

and the resulting concen-

potentially inefficient -as Table

1

would

tend to suggest. But Proposition 6 also makes clear when inefficient mixing will occur.

4

Stratification

Does

families'

and inequality

tendency to segregate into homogeneous communities make inequality more persistent?

The simple answer

and community

is

positive, as stratification

levels.

The

result

is

compounds

greater income inequality than would have occurred

remained integrated. Assuming perfect segregation (n

h'A

in the

£'(1)

/h'B

0,

which

is

=

1/2),

we

if

When

the empirically relevant case. In Section 4.2

show how segregation slows down convergence among

they do, the inequality

we make

different groups,

V

14

had

(8)

)

role.

families

have:

= F(h A ,h A )/F(h B ,h B > F(h A ,L)/F{h B ,L),

simple case where purchased inputs play no

>

disparities in educational inputs at the family

the

model

is

truly

reinforced

if

dynamic and

and can even generate poverty

Half of the gains 2 {Fi,(h A L) — Fi(/ib, L))

represents the private gains from trade accruing to a pair of A

B agents who exchange places. The other half is external: a marginal rise in L is more valuable, ceteris paribus,

in the community with more //-sensitive agents; see the expression for S' Interestingly, the results of Brooks-Gunn

,

and

.

et al. (1993) suggest that

FhL >

but Fll, L"

<

0.

13

But

traps.

we point out

first

More

overlooked.

that this story

specifically,

we

measure of inequality and the cost

A

4.1

discuss

subject to an important qualification, which tends to be

is

what

are usually implicit assumptions about the appropriate

which the rich are able to exclude the poor.

at

and

caveat: inequality in what,

what price?

at

usual approach, in both the theoretical and empirical literatures,

The

is

we

education levels or professional status of successive generations, as

that this

cost,

is

also the costs of educational investments leads one to

bequest), or

more generally the

Proposition 7 Consider

the general

n < 1/2, then

U

1

(h A )

— U 2 (Iib) >

=

1/2, the ranking

The same

2.

is

is

family inequality

What

is

is

where the

F(/ifl),

is

m

question

proved in the appendix.

It raises

1

capital plus

V/, r

>

0,

Vh p

>

0,

ensuring

left

and

right

(3).

15

utility levels.

hand sides correspond

1/2, the inequality

is

reversed,

and

if

d+

h!

and 2

they are distributed evenly:

respectively.

all

housing

initially

use this stronger condition for simplicity.

types and communities (as in

Wheaton

when

utility is linear.

some new and more

Who owns the

Proposition 7

,

the old question of whether child inequality or

it

identifying the recipients of the capital gains

land in communities

We

n >

the relevant concept (Stiglitz (1973)), but also

the cost to the rich of seceding from the poor?

means

if

children's total wealth

which allow stratification to occur and earn the rents which

15

(human

ambiguous.

true of inequality

This simple result

—

at a

lead to a very different answer.

and assume

1,

and integrated equilibrium. But

respectively to the stratified

n

children's total wealth

may

of parents. This

TJ{h A )

not obvious

it is

Taking into account not only the payoff but

0).

compare

model of Section

But

Equilibrium stratification need not increase inequality between rich and poor families'

1.

If

utility levels

>

bill (if t x

did in (8).

community quality and better schools come

the appropriate measure of inequality. Better

namely a higher rent p 1 > p 2 and/or tax

to track across families the earnings,

is

may

and

assets,

16

practical ones.

property rights or legal rights

create? In our model, answering this

losses

which stratification generates on

derived under the "neutral" assumption that

belongs to absentee landowners, or alternatively to the

The same

result can

be shown in a model with a continuum of

(1993)) using only (3).

16

Interestingly, a similar indeterminacy can be demonstrated in a model where agents self-select through a tradebetween school quality and tax rates, rather than land rents (e.g., Fernandez- Rogerson (1992)). Even though

there is no leakage" of community resources to outsiders, stratification need not increase inequality in utilities.

off

14

city's residents

1/2,

i

=

vB

may

but with no correlation between an agent's type and the location of her property

= A,B). A more

=

»jfl

or

0.

may

assumption might be that

realistic

Yet even then,

agents

own

need not increase inequality

stratification

not offset capital losses in

A

C 2 What

.

is

required

is

vA

>

>

va, VB

and

institutions

l/2n,

in total wealth: capital gains in

C

1

a larger share of the corresponding

which allow the

the generation and persistence of inequality by various collective

among

these

is

by raising -even

rich to capture the benefits of their secession,

temporarily- the relative cost to the poor of joining or remaining in a

Section 2.4). Prime

=

Va

=

Va-

What this points to is the role played in

practices

=

77,-

that the rich capture a larger share of the

rents which their exodus creates, and/or that the poor be left holding

losses:

the land: va

all

=

(i/,

community which

is

appreciating (see

whether enforced by law or custom. As long as

racial discrimination,

Blacks are simply not allowed to bid for land in the suburbs to which White families move, the latter can

regroup without dissipating too

are allowed in, those

much

of the resulting rents on higher land values.

who do come must pay

When,

later on, Blacks

the full value of the community's social capital. Although

the education gap between their children and those of their white neighbors will close, the gap in total

wealth will not.

In fact, the inequality in wealth which occurs the

and property values adjust can

in itself

the specification of Section 2.3, with n

non-land wealth, and each

own

=

+

p

1

-

p

2

)

-

u(z)

de jure segregation

is lifted

be sufficient to sustain de facto economic segregation. Consider

1/2.

their houses in

Suppose White and Blacks have the same amount

C

1

and

groups will remain separated even once free mobility

that u(z

moment

< w(F(h A )) -

u>(F(/»b))

C2

is

<

2 of total

respectively. Proposition 4 implies that the

— p2

such

In recent years, the

main

allowed, though a rent differential p 1

u(z)

-

u(z

+ p2 -

p

1

).

two

device used to "keep out the poor" has been the right given to a community's residents to impose zoning

regulations, which essentially operate as

minimum income

requirements (Durlauf (1992),Wheaton (1993),

Fernandez and Rogerson (1993a)). 17

The empirical

implication of these observations

is

that studies which attempt to measure the role of

peer effects, neighborhood spillovers or school quality in the intergenerational persistence of inequality,

should try to take into account not only labor earnings but also financial wealth:

'

how much

of the

human

EquivaJently, Durlauf (1993) assumes that a neighborhood's land price adjusts to the (equilibrium) value which

keeps out the marginally poorer family, only once all richer families have moved in and bought the land at cost. In

all these models, it still remains that some of the higher human capital passed on to children in rich communities

reflects the higher taxes paid by their parents.

'

15

wealth afforded to a child by a better educational environment

is

reflected in a reduction of the bequest

she receives? Answering this question might also help determine whether the peer effects found by Borjas

among members

(1992a)

of the

same ethnic group

truly represent "ethnic capital", or

whether they really

operate through local spillovers in ethnically segregated neighborhoods -as Borjas (1992b) would seem to

While the former are inherited

indicate.

a price in the form of rent or tax

through birth, the latter are subject to choice and carry

"for free"

differentials.

Bearing in mind this section's caveat about the links between stratification and different measures of

inequality,

we now extend

the analysis to a

to ghettos or poverty traps,

dynamic

and how those can

setting.

demonstrate how stratification gives

rise

turn adversely affect overall growth.

in

Overlapping generations

4.2

Let the two periods considered until

the distribution of

now

represent any two overlapping generations.

human wealth must be

more

capital markets are perfect (see Section 2.1

bequests: uj(h), y(h) represent labor income in the

The second condition

that the

first

things simple,

The

first

condition holds

generally), or alternatively

two periods of

life,

and

all

of

if

if utility is

linear

and

there are no financial

c' is

consumed

in old age.

requires that either inequality in children's earnings be the criterion of interest, or

generation of A's

who

secede capture the whole (present) value of rents created in community

leaving the J3's holding the less valuable land in

human

To keep

the only relevant state variable, determining both residential

equilibrium and the appropriate measure of inequality.

1,

We

community

2.

Thus

all

housing

is

owner-occupied, and

capital inequality translates directly into inequality of total wealth or utility.

For simplicity we abstract from purchased local public goods, so that

h'

=

F(h, L). Finally,

let

n

=

1/2;

thus whether integrated or segregated, the two groups always remain homogeneous. Also, in either case,

if tiA,t

>

/»b,i

the

same

is

true for the next generation.

The

generations of rich and poor segregate.

when F(h,L)

= Oh a L p

,

with

Xi+i

=

\og(h At+ i/hB,t+i)

\,+ i

=

log(hA,t+i/f^B,t+i)

a < a +

= axi

—

(o

+

/?

<

Therefore

resulting impact

1

<

9.

Xu

initial

is

satisfied for all (h,p,x), all

on the persistence of inequality

is

most

clear

In the integrated equilibrium, the level of inequality

converges to zero at the rate

/?)

if (3)

1

—

a.

In the stratified equilibrium,

conditions vanish at a slower rate, or even not at

16

all if

a

+ /? =

l.

18

Inequality can be even

more

returns in (h, L) jointly over

are

persistent

if

F(h,L) has decreasing returns

some range. Such

what underlies ghettos or

h alone, but increasing

in

local increasing returns, realized only through segregation,

(Benabou (1993), Durlauf (1992), (1993), Lundberg and

local poverty traps

Startz (1993)). Suppose for instance that local spillovers involve a threshold effect:

F(h, L)

where /

>

magnitudes

and L{x)

=

(h A ) x (hB) l

When

is

/ii,

(+ i

=

F(hi <t ,L t )\ given

geometric average. Hence the following result, which

f < hB,o < h*

and

h.A,t

=

//(l

—

0}

grow asymptotically

<

Lo-

at the rate

Under

—

"

(9)

is

fixed, basic level

we have

(9), this

1

>

hi,t+i

implies

illustrated in

capital accumulation be given by hi it +i

-1 /( 1- °))

1

Here

defined as the geometric average.

the two classes are segregated,

they remain mixed, we have

Proposition 8 Let human

/,

measured as deviations from some

h, L, F, etc., are

to be taken literally.

~x

= 6h° max{L -

=

—

h

>

0;

L t+ \ = F(L ,L

Figure

since

F{hi tt ,L3t ), as defined

integration, inequality converges to zero,

0.

Under segregation,

the

FhL >

=

is

not

= A,B. When

i

t )

capital

L

t

the

is

2.

human

in (9),

and

and both

let

hg,t

capital poor families

converges to h in finite time, while that of rich families grows asymptotically at the rate

In equilibrium, stratification occurs (due to

thus h'

F(hi tt ,hi t ),

t

human

all

6—1.

or the other factors discussed earlier) confining

poorer families to a steady state of low productivity and income, which cohabitation with better educated

dynasties would have allowed

them

to escape. 19

Two

recent papers provide supporting evidence for the

kind of non-convexity which underlies the ghetto phenomenon. Crane (1991) finds threshold effects in the

way a neighborhood's

professional

mix

influences local rates of high-school dropout

and teenage pregnancy.

Using a methodology specifically suited to detect non-linearities in income dynamics, Cooper, Durlauf and

Johnson (1993)

find that very

"Estimating such a

(1992b) finds that

low levels of mean county income generate poverty traps.

log-linear relationship for the descendants of

human

capital spillovers slow

immigrants to the United States, Borjas (1992a)

both equal about .25 and

down convergence markedly: a and

are statistically significant.

Tamura

(1991b) and Galor and Tsiddon (1992) present models which combine increasing returns at the indieconomy-wide technological externality, through which the poor eventually

catch up with the rich. The implicit assumption is that the rich do not segregate (i.e., limit interactions to their

vidual (country or family) level with an

own

group), as they do

when given the opportunity

in our model.

17

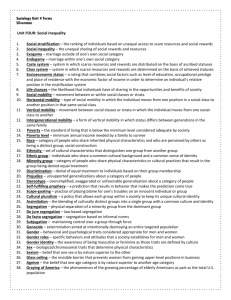

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

Stratification:

F(h[,h{)

+1 =

h{

Integration: hj

+1

= F(h(,L t ), L t =

(h^ (h{)^k

may

Stratification

even hurt the productivity and income of richer dynasties, when, in addition to

economy-wide

local interactions in education, the different classes interact at the global, or

simplest

way

in

B

educated

Hm =

nil*

is

as

more educated

A

agents be managers, and the

incomes, y A

=

A

agents workers.

managerial

is

The

which city and suburban residents can be bound together

the production of goods or knowledge. Let for instance the

less

level.

h A'

(Y

human

n)» ,yg

'

/

=

representative firm's output

capital

(Y

h B°

Hw =

and

/ (1

— n)hs

(1

— n))»

is

complementary factors

2

V =

(//"m

worker

"

-

+ Hw !~r~)

human

capital.

are clearly interdependent.

'

,

The

in

where

resulting

Task assignments are

exogenous, but a model with occupational choice and competitive labor markets would have very similar

implications (Benabou (1993)). 20 Instead of production complementarities, agents could be linked through

economy-wide knowledge

spillovers (Lucas (1988),

public goods. These ties can

all

Romer

h,

H

is

some economy-wide index of human

which represents a basic

to heterogeneity

is

shall

1

the

Under segregation, human

among

degree of complementarity

like L, is

(10)

measured as deviations from

local index L, the sensitivity of

H=

(/iyi)

as in Proposition 8,

and

and

all

When

agents' skill levels; see

a geometric average:

same conditions

as:

~x

capital. All variables are still

integration, inequality converges to zero,

In this

H

and earnings. Like that of the

level of skills

simply assume that H,

Proposition 9 Assume

Under

(1991b)) or nationally funded

a key determinant of the costs and benefits of stratification.

this sensitivity reflects the

we

Tamura

be captured by writing individual productivity

y(h)=h x

where

(1986),

n

(/iB)

H

is

Benabou

a

CES

H

index,

(1992). Here

1-n

.

the production technology (10).

earnings grow asymptotically at the rate

8—1.

capital inequality keeps rising, but all earnings converge to h in finite time.

economy, productivity growth slows down and eventually peters out because the secession

of "managerial" dynasties prevents "worker" dynasties from acquiring the skills necessary to keep up. 21

Alternatively,

Tamura

(1991a) and Benabou (1992) present models where increasing returns cause agents to

specialize in imperfectly substitutable intermediate inputs.

essentially the

'The

same

The induced mapping from human

results of Glaeser,

Scheinkman and

Shleifer (1993) confirm the

force, in contrast to a high

concentration of

human

income

is

importance of a well educated general labor

capital on a small elite. In explaining a city's growth, they find

the proportion of residents with 12 to 15 years of education (high school graduates and

more important and

capital to

as the one below.

statistically

more

some

significant than the proportion with higher education.

18

college) to be both

Making those

Douglas)

skills essential to

When

only a convenient shortcut.

is

general model h'

=

H

production (by defining

F(h,L,E), reductions

as the geometric average, or

education uses real resources (schools,

in productivity feed

and even

one,

in the

absence of threshold

and income to which

capital

self-defeating

depends

effects, stratification

rich families converge.

respectively by the degrees of complementarity \jz

9,

Section

There

3).

is

But over the long

society

may

more than

stratification benefits the rich

H

as in the

human

is

capital

greater than

can lower the steady-state path of

or not the secession of the rich

Cobb-

is

human

ultimately

on the relative costs of local and aggregate heterogeneity, measured

in particular

As shown by Proposition

Whether

/»b in

as a

R&D),

back into each family's

accumulation. Thus even when the elasticity of substitution a between h A and

Y

it

and l/a

in local

and global interactions.

be faced with an intertemporal tradeoff. In the short run,

hurts the poor, so that overall growth increases (S"

>

in

run, excessive heterogeneity acts as a drag on growth, affecting all lineages.

then an incentive for the

rich,

subsidize the education of the poor.

provided their intergenerational discount rate

They could

for instance agree to

of schools, neighborhoods, networks, and so on.

We

may be

low enough, to

inter-community transfers (Cooper

(1992)) or support switching to a system of national funding (Benabou (1992)).

that purchased inputs play no role in Proposition 9, these

is

But as shown by the

fact

poor substitutes for the actual integration

return to this issue

when

discussing policy later on.

School financing

5

We now

explicitly incorporate local school expenditures

and taxes into the

analysis.

We

show how they

represent an additional segregating force, then examine the consequences for efficiency and inequality.

These

results will also

5.1

The

We

most simple

schools financed by

case,

conducted

in the

next section.

where agents are risk-neutral, capital markets

lump-sum or property taxes (with

that each family's tax

is

for the policy evaluation

choice of education expenditures

start with the

ment

form the basis

bill

inelastic lot size, these are equivalent).

and

local

This implies

equals per-student expenditures E, and that a community's educational invest-

not constrained by

how a simple adaptation

frictionless,

its

of the

tax base. Section 5.4 considers income tax financing, and Section 5.5 shows

model can incorporate wealth

19

constraints.

We assume

that in a

community

with composition (x,

1

—

x) and spillover quality L, education expenditures are determined as:

Er{z,L)

We

tinuous

as the

= aigmax{zF(h A ,L,E) + (l-z)F(h B ,L,E)-(l + r)E}.

choose this decision rule for two reasons. First, unlike majority voting,

manner both the proportions and the preferences of

outcome of unrestricted vote-trading. 22 Second,

munity composition;

(11)

E

it

local residents. It

it

a simple, con-

reflects in

can

in fact

be interpreted

yields the efficient outcome, conditional

this allows us to highlight the issue of inter- rather

than inira-community

on com-

efficiency.

Equation (11) implies:

EE

_

dE-(x.L)

with

F},

all

results,

E

,

i

= A,B

stands for FhE(hi,L,E'(L,x)), etc.

simplifies notation

varies with

g (a) =

Ah

EE

.

~

Fju

-Fee

The approximations hold when Ah/h

Although

this condition

is

+ fegfc + a - *^ L 'w

u - a-**&-(!-«)*&

are complements, rich communities

may

*i>i*L.

- fbe

Ah+ jj^. L

E*(x, L(x))

>

(

-Fee

i2)

thus spend more on their students than poor

same environment, students from poor backgrounds would have

a higher marginal product of education expenditures than those from richer families (FhE

<

0)-

Stratification

Having determined E(x) andt(/i,p,i)

or equivalents in

SEG =

(1

+

=

E(x), we

now

replace

families

who

them in

the bid-rent differential

r){Rt {h A ,p,x) - Rx(h B ,p,x)) = (F£ - Fg)

expression defines the net private gains, in terms of children's

B

=

as:

ones, even though, were they placed in the

5.2

small,

is

not required for any of the

and makes intuitions more transparent. The school budget E(x)

community composition

When E and L

*/*

xF$,.+(l-*)Fg

derivatives evaluated at (h, L(n), E(n)).

it

I*

-xF*

EE~^"-~*->*EE

E -(l-z)F§E

dL

where

nR

F$-F§

9E'{t,L)

human

U + (Fg

capital, to a

Rh x (h, p,x),

- F§)E'.

marginal pair of

A

This

and

switch places during the stratification process:

a weighted average of each group's preferred level, E*(x,L) = 0(x)E A (L) +

have implications very similar to those of (11). Note that we assume Fee <

throughout. Also, the case of most interest is when the equilibrium involves a high degree of stratification; as

stressed by Tiebout (1956), there is then near-unanimity in each community.

22

(1

A political process resulting in

— 0(x)) E (L), 0'(x) > 0, would

20

SFG

The term

-

(F A - F B + (F A - F§) ££bl±Q=£2£m

*

((^L + ^ff^Ji' +

in brackets represents the

education and community quality.

")

l<

<*fi- ff?'

+

(13)

^ffA^A/i.

comp/emen<an<y, both direct and indirect through E, between parental

The

last

term, always positive, captures the greater incentive of each

type of agent to join a community where individuals with similar preferences, being more numerous, have

greater weight in the setting of policy.

the absence of local externalities

stratification

(FL

The

-

implication of (13)

first

The second one

0).

that stratification always occurs in

that local funding of education

is

< SEG). 23

(Fm <

which would otherwise not have occurred

is

This

is

may

induce

probably an important

piece of the explanation for the difference in the extent of stratification between the United States

and

most other industrialized countries.

Efficiency

5.3

Recall that E(x)

is

chosen optimally, given

x.

thus again determined by the concavity of net

S(x)

From

(11)

=

efficient

S'

(surplus-maximizing) residential allocation

community output, now defined

= x F(hA ,L(x), E(x)) + (l-x) F(h B

and the envelope theorem,

S"

The

= F A - FB +

x

L(x), E(x))

,

F£ +

(1

-

i)

Ff

as:

- (1 + r) E(x)

.

is

(14)

Then, using (12)

yields:

2(F£-F?)L' + (xF£L + (l-x)FBL )(L'y + (xF£ + (l-x)F?)L"

(15)

-{xF£B + (l-x)F§E

The

first

)

(£') 2

three terms are due to local spillovers, which affect education both directly and through their

interaction with E. Their interpretation

is

the optimal adjustment of expenditures to

the

same

as in (7).

The

last

term, always positive, arises from

community composition i and quality

L.

Absent local

spillovers

(and imperfections, say, in capital markets), the tendency to segregate in response to differing preferences

over education promotes efficiency (Tiebout (1956)). In general, however,

23

in

De Bartolome

(1990) considers the case where Fhl

<

it

may have

= Fel < Fhe and where these two opposing effects result

an asymmetric but incompletely stratified equilibrium. Although his political mechanism

,

is different, this

can be

< min{2n, 1} to the equation f^n _ x SEG(x)dx = F(Iia,L(x ),E(x

- [F(h B Lix ), Eix )) - F(h B L(x*),E(x 2 ))] = 0.

understood as interior solution n

F{h A L(x 2 ), E(x 2 ))

the opposite effect:

<

1

,

x

1

i

1

,

21

))

—