Hi 9080 02617 6575 3 DUPL

advertisement

DUPL

MIT LIBRARIES

!|

111

!

I

I

II

I

II

3 9080 02617 6575

l|!li

i

Hi

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/economicfutureofOOblan

yj

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

The Economic Future of Europe

Olivier Blanchard

Working Paper 04-04

February 1, 2004

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

This

MA 021 42

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http://ssm.com/abstract=500l83

The Economic Future

Olivier Blanchard

February

Europe

of

*

2004

1,

Abstract

After three years of near stagnation, the

Many doubt

Over the

in

Europe

is

definitely gloomy.

last thirty years,

is

room

for

I

argue that

optimism.

productivity growth has been

much

higher in Europe

the United States. Productivity levels are roughly similar in the European

Union and

some

in

that the European model has a future. In this paper,

things are not so bad, and there

than

mood

in

the United States today.

The main

difference

is

that Europe has used

of the increase in productivity to increase leisure rather than income, while

the U.S. has done the opposite.

Turning to the present, a deep and wide ranging reform process

reform process

is

taking place. This

driven by reforms in financial and product markets. Reforms in

is

those markets are in turn putting pressure for reform in the labor market. Reform

in

the labor market will eventually take place, but not overnight and not without

political tensions.

These tensions have dominated and

the news; but they are a

Written

for

symptom

will continue to

dominate

of change, not a reflection of immobility.

the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

I

thank Philippe Aghion, David Autor, Tito

Boeri, Ricardo Caballero, Guillermo de la Dehesa, Francesco Daveri, Xavier Gabaix, Francesco

Giavazzi,

Thomas

Kneip, Giuseppe Nicoletti,

Stefano Scarpetta, and Andrei Shleifer

Thomas

for discussions

Philippon, Ricardo Caballero, Andre Sapir,

and comments.

Future of Europe

After three years of near stagnation, the

The two economics books on the

mood

bestseller's

in

list

Europe

is

definitely gloomy.

France in 2003 are called "La

in

France qui Tombe" (the Fall of France) (Baverez [2003]), and "Le Desarroi Francais" (the

French Disarray) (Duhamel

of France

and

its

[2003]).

economic future, a future

implemented, France

will steadily lose

EU

"the world's most

as largely

The most

and

fit

face,

its

dramatic reforms are

competitors.

but their boasts, such as the goal

Lisbon conference in March 2000 to make the European Union

dynamic and competitive economy within ten years" are seen

empty and

pathetic.

articulate diagnoses argue that, like Stalinist

European model worked

place, the

offer a pessimistic vision

in which, unless

ground against

Governments are trying to put on a good

adopted at the

Both books

growth

in another

well for post-war Europe, but

is

time

no longer

for the times.

For

much of the post-war

period, the argument goes,

European growth was "catching

up growth," based primarily on imitation rather than innovation. For such growth,

large firms, protected in both

They could do much

of the

goods and

R&D

in-house.

with suppliers of funds. They could

their workers.

The

firms, workers,

Now

offer

financial markets, could

They could develop long-term

rents generated in the goods markets could be shared between

and the

state,

and

to help finance the welfare state.

that European growth must increasingly be based on innovation,

come

now

that

European model has be-

dysfunctional. Relations between firms and suppliers of funds, between firms

their workers,

must

all

be redefined. This requires nothing short of a complete

transformation of economic and social relations. 1 So

far,

Europe has not

seems increasingly

1.

relations

long-term relations and job security to

firms cannot be insulated from foreign competition, the

and

do a good job.

Many

of these

risen to the challenge. Instead,

themes are developed

as the "Sapir Report" [2004].

in

it

the argument concludes,

petrified,

a recent report to the European Commission, known

Future of Europe

unable to engage in fundamental reforms. This

is

why

have a more optimistic assessment. In this paper,

I

Things are not so bad. Over the

•

been much higher

in

is

that Europe has used

leisure rather

A

•

some

in the

is

want to argue

that:

EU

growth has

United States. Productivity

and

in the U.S.

The main

levels

difference

of the increase in productivity to increase

than income, while the U.S. has done the opposite.

deep and wide-ranging reform process

process

bleak."

is

last thirty years, productivity

Europe than

are roughly similar today in the

I

the future

is

taking place in Europe. This

driven by reforms in financial and product markets. Reforms in

those markets are in turn putting pressure for reform in the labor market.

Reform

in the labor

and not without

market

will eventually take place,

political tensions.

but not overnight

These tensions have dominated and

continue to dominate the news; but they are a

symptom

will

of change, not a

reflection of immobility.

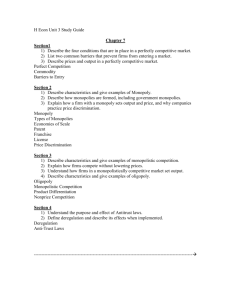

The paper

organized as follows: Section

is

ductivity, income,

1

and employment. Section

market reforms. Section

looks at the facts, focusing on pro2 focuses

on

3 discusses implications for labor

financial

and product

market reforms. Section

4 concludes.

Some

1

Two

Facts

facts are often cited

by Euro-pessimists:

GDP

per person in the European

Union, measured at purchasing power parity (PPP) prices, stands at

per person in the United States. Not only that, but this ratio

30 years ago.

These

is

the

70%

same

of

as

GDP

it

was

3

facts are correct.

They suggest a Europe stuck

at

a substantially lower stan-

dard of living than the United States, and unable to catch up. This interpretation

2.

For example, a description of

3.

As

the

PPP

Germany along

of the time of this writing, the actual

exchange

rate.

these lines is given by Siebert [2003].

exchange rate of 1.20 dollars to the Euro is close to

Future of Europe

would be misleading however, and the reason why

ble

1.

EU-15

Table

gives

1

GDP

and

in general,

for

twofold.

is

for

The

quite simply, that

Table

1.

know France

I

PPP GDP

in Ta-

for

choosing France as an example of a European

first is

one often perceived as a poster child

is,

numbers

per hour, and hours per capita for the

and often below (showing the numbers

to unwieldy tables)

in the

France in particular, as ratios to the United States,

both 1970 and 2000. The reason

country, here

GDP

per capita,

shown

is

that

for the

it is

for all 15 countries

a large European country, and

European malaise. 4 The second reason

better than the other

per person,

would lead

PPP GDP

European

countries...

per hour, and Hours per

person, 1970 and 2000: U.S., EU-15, and France. (U.S. =100)

GDP

per person

1970

2000

1970

2000

US

Source:

GDP

per hour

Hours per person

1970

2000

100

100

100

100

100

100

EU-15

69

70

65

91

101

77

France

73

71

73

105

99

67

EU Ameco

data base.

The

first

two columns, which show the evolution of

tive to the

GDP

United States, confirm the two facts presented

per capita relaearlier:

The gap

between the EU-15 and the U.S. has remained roughly constant; the gap

between France and the U.S. has even increased a

4.

For the same reasons,

Germany would

also

little.

be a natural candidate. But the German

cation of the early 1990s leads to both German-specific issues, and to issues of

looking at periods which include reunification.

reunifi-

measurement when

Future of Europe

The next two columns show however that

•

GDP

per hour worked, has increased

United States. Relative

in

EU

labor productivity, measured as

much

faster in

Europe than

productivity, which stood at

65%

in the

of the U.S.

1970 now stands at roughly 90%. French labor productivity now exceeds

U.S. labor productivity.

The

•

last

two columns, which give hours worked per person

worked divided by

shown

hours

total population) give the key to the divergent evolutions

in the earlier

relative hours

(total

columns. As relative

worked decreased

a roughly constant relative

EU

labor productivity increased,

in roughly the

GDP

same proportion, leading

to

per capita.

In other words, had relative hours worked remained the same, the

EU

would have

today roughly the same income per capita as the U.S. The stability of the U.S-EU

gap

in relative

There

is

income per capita comes from the decline

another way of stating the same underlying

rather than relative evolutions, which

is

in

hours worked.

facts,

looking at absolute

quite striking. In the United States, over

GDP per hour increased by 38%. Hours per person also

GDP per person increased by 64%. In France, over the same

the period 1970 to 2000,

increased, by 26%, so

GDP

period,

so

GDP

per hour increased by 83%. But hours per person decreased by 23%,

per capita only increased by 60%. In that

light,

the performance of France

(and of the European Union in general) does not look so bad:

A much

higher rate

of

growth of productivity than the U.S., and, as one might expect given that

is

a normal good, the allocation of part of that increase to increased income, and

leisure

part to increased leisure.

Is this

too polemical a way of stating the facts?

measured? Can the decrease

in hours

worked

in leisure?

What about

relative to

Europe? These questions require a

Is

really

labor productivity correctly

be interpreted as an increase

the recent past, where the U.S. appears to have accelerated

closer look at the facts.

Future of Europe

Productivity

1.1

There are

two obvious issues of interpretation with the productivity num-

at least

bers presented above.

many European

In

countries, the

unemployment

rate

is

high, higher than in the

United States, and high unemployment disproportionately affects low

In a

number

average wage

European countries

of

is

higher than

exclusion of low

By

skill

it is

in the

workers.

minimum wage

the ratio of the

also,

skill

to the

United States, leading again to the potential

workers from employment.

excluding more low productivity workers from employment, both factors tend

to increase

countries,

measured labor productivity. In comparing labor productivity across

we may want

to control for this effect.

compare the U.S. and France

tivities, to

example,

is

to

to do so,

assume that wages

minimum

relative French

minimum wage and

if

we want

reflect

use the information from the U.S. wage distribution to

wage distribution between the

relative

for

One way

fill

to

produc-

the French

the (lower) U.S.

wage, and then to compute the resulting productivity adjust-

ment. Such a computation was

made

in

a comparison of productivity in France,

Germany, and the United States by McKinsey

([1997],

updated

[2002]); this

com-

putation gives a downward adjustment for French labor productivity of about 6%,

so yielding roughly similar labor productivity in both countries.

The second

issue

is

that labor productivity reflects not only the state of technology,

but also the capital-labor ratio chosen by firms. Increases

in the cost of labor

lead firms to decrease labor relative to capital, leading to an increase in labor

productivity.

To

control for this, the obvious solution, at least conceptually,

is

to shift from comparisons of labor productivity to comparisons of total factor

productivity.

The capital-output

Europe than

in the U.S.

is,

for

example,

30%

Based on

ratio appears indeed to be typically higher in

OECD

higher in France than

series for the business sector, the ratio

it is

in the U.S.

A

back of the enveloppe

computation suggests that, starting from roughly equal labor productivities (which

is

where we started

after the correction above), the level of

French

TFP

is

roughly

Future of Europe

10%

In

lower than that of the U.S. 5

summary, the two adjustments lead to a more modest assessment of European

productivity relative to U.S. productivity. But the

particular,

remain within close range of U.S.

EU

in general,

and France

in

levels.

Hours Worked

1.2

Should we interpret the large decrease

in

hours worked per person in Europe as the

income as productivity

result of preferences leading to the choice of leisure over

increased?

Or should we

interpret

it

instead as the result of increasing distortions,

such as higher taxes on work, an increase in the

early retirement programs,

minimum

wage, generous or forced

and so on? 6

Let's start with a closer look at the facts. Given that different margins

(how many

hours to work, whether to be employed or unemployed, whether to participate or

not) imply different choices,

it

is

decomposing the change

useful to start by

in

hours worked as follows:

A\n(HN/P)

The change

= AlnH + Aln{N/L) + A\n(L/P)

= AlnF + Aln(l-u) + Aln(I,/P)

in hours

worked per person,

worked per worker, H, plus the change

5.

The computation

is

—

(1

— a) A

In

K

,

countries, rather the change in time. Rewrite

A In A').

If

labor productivity

6.

30%

in the ratio of

is

it

as:

much

the labor

A here refers to the difference across the two

A In A = q(A In Y — A In N) + (l — a)(A \nY -

the same in both countries, and the share of capital

shadow

is

is

10%

1

difference in

—q

is

TFP

equal

levels.

the following: In trying to compare welfare

price should

use the wage, in which case the measure of welfare

use a

iV, to

where

Another way of asking the same basic question

we

employment,

difference in the capital output ratio leads to a

rather than just income per capita, what

or should

equal to the change in hours

is

as follows. Start with the standard expression for the Solow residual:

A In A = A In Y — qA In N

to 0.33, then a

HN/P,

we

use to weigh leisure? Should

roughly similar

in

Europe than

in

we

the U.S,

lower shadow price, in which case Europe remains substantially behind.

Future of Europe

force,

L

(equivalently, one

ratio of the labor force

Applying

L

minus the unemployment

to population,

P

rate), plus the

change

in the

(equivalently the participation rate).

decomposition to the various European countries yields two main

this

conclusions:

•

Most

sense,

of the decrease in hours worked per person has come, in an accounting

from the decrease

increases in

Applying

in hours

unemployment

for

example

gives -23%, -7%,

and

worked per worker, rather than from

or decreases in participation rates.

this formula to

7%

for the three

France for the period 1970 to 2000

terms on the

right.

Hours per worker

decreased by 23%, from 1962 hours per year in 1970 to 1550 hours per year

in 2000.

in

The unemployment

1970 to

from 0.42

9%

in

in 2000.

by 7 percentage points, from

2%

the participation rate increased by 7%, going

1970 to 0.45 in 2000. In this decomposition, France appears

representative of other

•

And

rate increased

European

countries.

Focusing on the decrease in hours worked per worker, most of the decrease

has come from a decrease in hours worked per

full

time worker, rather

than from an increase in the proportion of part time workers. 7 In France,

for

example,

full

time wage earners worked an average of 45.9 hours

1970; they worked only 39.5 hours in

the decrease has been

1999— a 15.0%

more pronounced, due

to the

in

decrease. Since 1999,

two "35- hour" laws

passed in 1998 (mandating a reduction of the workweek to 35 hours by 2000

for firms

with more than 20 employees) and

in

2000 (mandating a similar

reduction by 2002 for public sector employees, and for firms with

20 employees). 8

The

latest available

less

than

number puts the average workweek

at

7.

The motivation for this further decomposition is that some of the increase in part-time

employment may not have been voluntary. 20% of part time workers in Europe in 2000 said it

was because they could not find full-time jobs. The corresponding number for the U.S. is 8%.

Whether the shift to 35 hours should be seen as voluntary is a matter of debate. The promise

8.

to pass such a law was probably the main factor behind the victory of the Socialist government

in 1997. Whether or not voters actually understood the income/leisure trade-off is now hotly

debated.

Future of Europe

38.3 hours in 2001, a

The

18%

decline since 1970.

much

facts therefore suggest that

from a decline

in

hours worked per

But

of workers.

of the decline in hours

full

time worker.

one should interpret

that, over thirty years,

It is

worked has come

reasonable to think

this choice as voluntary

This choice

this does not yet settle the issue.

of the interaction of preferences

9

and an the increase

of increasing tax distortions faced by workers.

on the part

may be

the result

in productivity, or the result

And, indeed, the evidence suggests

that marginal tax rates (constructed by adding marginal income and payroll tax

rates,

and consumption tax

(10-15%

most

for

The answer

as to

EU

have increased more

countries, relative to about

how much of the

or changes in tax rates

preferences,

rates)

8%

in

Europe than

for the U.S.)

depends on what assumptions one

is

willing to

and the implied strength of income and substitution

has argued that

to the increase in taxes.

and the large implied

all

of the decrease in hours in

One can

10

decrease in hours can be attributed to preferences

study, Prescott [2003], using a utility function logarithmic in

leisure,

in the U.S.

make about

effects.

In a recent

consumption and

Europe could be attributed

object however to his assumptions about

elasticity of labor supply.

utility,

More importantly, within Europe,

the cross-country relation between the decrease in hours and the increase in tax

rates

weak.

is

A

revealing example here

that of Ireland. Average hours worked

is

per worker in Ireland have decreased from 2140 in 1970 to 1670 in 2000, a

decrease over the period, and hours worked by

in line

with the European average.

11

depressed labor market: Ireland has

time workers have decreased

full

This decline can clearly not be blamed on a

boomed during

the period, has seen major

migration, an increase in participation rates, and

unemployment

Nor can

The

it

be blamed on an increase in tax

rate has been small, about

9.

25%

3% compared

rates.

to the

8%

is

now very

in-

low.

increase in the average tax

increase in the U.S. Turning

is an outlier, it is useful to note that the country with the

worked per year per worker is Germany, with 1450 hours compared to

Lest one conclude that France

lowest

number

of hours

France's 1550.

For detailed evidence on marginal tax rates, and their recent evolution, see Joumard [2001].

This statement is based on the evolution of hours worked by full time workers in manufacturing, the only series available for the period at hand.

10.

11.

Future of Europe

10

more formal evidence, econometric estimates based on panel data evidence

to

Nickell [2003] for a recent survey

more modest

and discussion) typically

find a significant, but

role for taxes in explaining the decline in hours per capita.

may

imply that the evolution of tax rates

(see

They

explain about a third of the decrease in

hours per capita in Europe over the period.

To summarize: Most

Europe

is

reflects

of the decrease in hours per capita over the last 30 years in

a decrease in hours worked per full-time worker, a choice which

be made voluntarily by workers. The remaining issue

likely to

is

how much

of

comes from preferences and increasing income, and how much from

this choice

increasing tax distortions.

with a large role

left for

I

read the evidence as suggesting an effect of taxes, but

preferences.

12

Evolutions Since the Mid-1990s

1.3

Looking

not

tell

at productivity

growth since 1970, or at productivity

the whole story. Indeed, part of the Euro-pessimism

mid

since the

1990s,

and the

feeling that the U.S.

is

is

levels today,

may

based on evolutions

again gaining advantage on

Europe.

The

basic

The

table gives

numbers are given

TFP

1980s, for the 1990s,

The

in

Table

2,

growth numbers

and

table yields three

for each half

main

was the

for the U.S., the

result of a first half

et al [2002a]

EU, and France,

for the

decade of the 1990s.

conclusions. In the 1980s,

higher than in the U.S. In the 1990s,

this

based on the work of Van Ark

it

European

TFP

was roughly the same as

growth was

in the

US.

And

decade with Europe growing faster than the U.S.,

but a second half decade with the U.S. growing faster than Europe.

12.

There

is

plenty of anecdotal evidence that Europeans enjoy their leisure more than their U.S.

counterparts.

I

have looked

for

more formal evidence from surveys on happiness and

countries, but have not been able to find

it.

leisure across

Future of Europe

Table

2.

11

Total factor productivity growth: U.S.,

EU, and France, 1980-

2000. (Percent per year)

Van Ark

1980s

1990s

1990-1995

1995-2000

U.S.

0.91

1.06

0.74

1.39

EU-15

1.45

1.04

1.36

0.72

France

1.90

0.68

0.89

0.38

based on just

five

[2002a], Tables 19

and A7.

Reaching conclusions about trend changes

a dangerous exercise.

13

in

Cyclical factors and

TFP

measurement

issues

much

like

is

may well dominate

any trend change over a short period. But we also know that the

of this decade have looked very

years of data

first

three years

the second half of the previous decade,

with very high

TFP

TFP

Europe. For this reason, most observers now believe that we have

growth

in

growth

in the U.S. despite a recession,

and continuing low

indeed seen a change in relative trends, starting around 1995.

The nature and

the origins of the change have been the subject of a large

of recent work.

Some have emphasized

both

in the

amount

the role of information technologies (IT),

IT-producing and the IT-using sector. Some have emphasized

differ-

ences between evolutions in manufacturing and services. For these reasons, Table 3

presents labor productivity growth rates for each half decade of the 1990s, for the

U.S. and the

EU

(I

leave France out, so as not to clutter the table), distinguishing

between IT-producing, IT-using, and non-IT-using sectors and between manufacturing and services.

The

table

is

based on the work of Van Ark et

al

[2002b],

13. The standard deviation of annual productivity growth in the U.S. or Europe is roughly 1%.

Assuming no correlation between the two growth rates, this implies that the difference betw een

five-year average growth rates in Europe and in the U.S. has a standard deviation of (-^2/5) =

0.63.

Future of Europe

12

which pays careful attention to problems of comparability across countries, using

in particular

harmonized price deflators

deflators for

IT varies widely across countries, and makes

for

IT (the construction of national price

direct comparisons of

national figures unreliable).

Table

3.

Labor productivity growth, IT producing/IT using, Manufacand EU, 1990s. (Percent per year)

turing/services: U.S.

EU

US

Share

1990-95

1995-2000

1990-95

1995-2000

1.1

2.5

1.9

1.4

2.6

15.1

23.7

11.1

13.8

4.7

3.1

1.8

4.4

6.5

Overall

IT producing

Manufacturing

Services

IT using

Manufacturing

Services

Non IT

4.3

-0.3

1.2

3.1

2.1

26.0

1.9

5.4

1.1

1.4

9.3

3.0

1.4

3.8

1.5

43.0

-0.4

0.4

0.6

0.2

using

Manufacturing

Services

"Share" in the

Van Ark

The

•

first

column

[2002b], Tables 5

is

the share of the sector in

and

in percent. Source:

6.

table yields the following three

Some have argued

US GDP,

main conclusions:

that the slowdown in productivity growth in Europe since

1995 reflects primarily a slowdown in productivity growth in manufacturing

([Daveri 2003]).

The

table shows that manufacturing productivity growth

outside the IT producing sector has indeed declined (this decline

in all

rate

EU

countries, except for the Netherlands.)

which

is

still

But

it

is

present

has declined to a

higher than that of the U.S. This appears more to be

Future of Europe

13

evidence of the end of catch-up growth than of any emerging European

inability to innovate in manufacturing.

•

Some have argued

that Europe has missed the IT revolution, in the sense

that IT production, and

more limited

what

associated high productivity growth, has been

Europe. The table cannot by

in

needed

is

its

itself

answer the question, as

in addition to the information in the table

the IT producing sector in

GDP

in the U.S.

and

This share has been indeed slightly smaller in the

the share of

European

in

EU

is

than

in the

versus 7.3%. But this average hides differences across countries.

of countries, in particular Ireland

countries.

US, 6.0%

A number

and Finland have shares which exceed

10%.

•

Finally,

some have argued that the main problem

use rather than the production of IT.

One way

to proceed

is

of

The evidence

to look at the contribution of

Europe has been

in the

somewhat mixed:

is

IT

capital to

growth

in

the IT-using sector. This exercise was carried out by Colecchia and Schreyer

[2002] for

is

example, using a growth accounting framework. Their conclusion

that investment in IT was substantially higher in the U.S. than in Europe

in the

second part of the 1990s, and so led to more labor productivity growth

in the

IT-using sector in the U.S. than in Europe. However, such a conclusion

is

only correct

if,

if

the assumptions underlying growth accounting are correct,

in particular, the

investment in IT in the U.S. had an expected rate of

return equal to the user cost of that capital.

this

was the

case,

Many

observers doubt that

and the evidence on IT investment since 2000 suggests

that there was indeed substantial overinvestment in IT in the second half

of the 1990s.

Another way to proceed

ity

is

to look directly at changes in labor productiv-

growth, without trying to separate between the contribution of capital

accumulation and the contribution of

Table

3.

The numbers suggest

TFP

growth. This

is

what

is

done

in

that there was indeed a large difference in

labor productivity growth in the IT-using service sector, 5.4% in the U.S.

Future of Europe

14

versus 1.4% for the

EU. This

difference

is

important because the sector ac-

GDP, 26%

counts for a substantial proportion of

in the U.S.,

21%

in the

EU.

Can one

trace this difference to specific sectors, so as to get a sense of

right, or

by Van Ark

concludes that the difference

et al

Europe did wrong?

A

what the U.S. did

to three sectors: retail trade, wholesale trade,

growth

in this third sector

more

is

and

detailed exploration

nearly fully attributable

securities. Productivity

seems largely attributable to the increase in

internet-based and other transactions associated with the bubble

of the late 1990s. This leads to a focus

of the

main

on

retail

and wholesale trade as two

factors behind the difference between the U.S.

the late 1990s, a conclusion shared by a

[2001] for the U.S.,

McKinsey

number

[2002] for a

economy

EU

and the

of other studies

in

(McKinsey

comparison of France, Germany,

and the U.S.)

What

should one conclude for the broad examination of the facts? Contrary to

widespread perceptions, Europe has done very well over the

some European

last

30 years. Indeed,

countries, such as France, have a level of productivity roughly equal

to that of the United States.

The income

level

has not caught up with that of the

United States, but only because of a different choice between income and

leisure.

In the recent past, the U.S. has clearly done better than Europe. Clearly,

Europe

is

somewhat behind

is

not clear that this was wrong.

in

IT production.

well in the United States; such

visible in

I

also has invested less in

IT

capital,

sectors, trade in particular, have

an increase

Europe; what this means

look at the trade sector.

in productivity

for the future

shall return to

it

in the

is

hard to

but

it

done very

growth has not been

tell

without a closer

next section.

Reforms In the Financial and Product Markets

2

The

in

Some

It

last fifteen years

have seen dramatic changes in goods and financial markets

Europe. Most of these changes can be traced to a reform process

in

which

Future of Europe

"Bruxelles" (this

in Bruxelles)

to

way Europeans

the

is

has played a central

refer to the

role, forcing (or

European Commission, located

allowing?) national governments

implement reforms they would probably not have implemented on their own.

The Role

2.1

A

15

central

of Bruxelles

document here

is

the "White Paper" written in 1985 by the European

Commission, under the presidency of Jacques Delors. At the time,

the European Union needed a

new and more ambitious

it

was

felt

that

goal, and, in that report,

the Commission laid a plan for achieving a fully integrated European internal

market by 1992. 14

The

report offered a timetable to achieve the elimination of physical barriers,

of fiscal barriers,

products

and of technical barriers-the

in place in different countries.

different standards for individual

Realizing that harmonization of rules and

regulation might be difficult to achieve or even lead to deadlock, the report argued

for using,

whenever possible, the more wide-ranging principle of "mutual recogni-

tion"

a product

there

"If

:

is

It also

is

lawfully manufactured

no reason why

emphasized the

competition

it

and marketed

in

one member state,

should not be sold freely throughout the community".

role of competition policy in achieving

in the internal

and maintaining

market.

At the end of 1992, most of the agenda

set out in 1985

a highly symbolic step, border controls

for

was indeed achieved, and,

goods were eliminated (Financial market

integration took longer, but has accelerated with the adoption of the

The

current plan

is

in

Euro

in 1999.

to have a fully integrated financial market by 2005).

The

process of reform continued however, through the implementation of competition

policy.

Today, competition policy and fights between the current Commissioner,

Mario Monti, and national governments, often make the news.

European competition policy comes

into play only

Surely by EU standards, but indeed by any standard,

(Commission of the European Communities [1985]).

14.

when

this

is

trade between

member

a remarkably clear document

Future of Europe

states

is

16

affected. In practice, given the integration of markets, this still leaves

a

very broad scope for Bruxelles to intervene. European competition policy covers

four areas, in which the

national

own competition

The

•

Commission

either

authorities

can act alone, or shares

and law courts:

its

powers with

15

elimination of anti-competition agreements or abuse of dominant po-

sition. It

can prohibit an agreement, and even impose

fines,

up to 10% of

the world turnover of the relevant parties. Examples of recent interventions range

from a ruling against British Airways

minimum

The

•

fee scale.

liberalization of monopolistic sectors.

opening up of markets.

It

is

example to the opening up

The Commission can

of the

market

for

mobile telecommunication

member

states,

when granting

European Union competition

exclusive rights, comply with the

for

initiate the

a 1996 Commission directive which led for

services to competition. It also checks that

1997

with travel

by the Belgian Architect Association of

agents, to a ruling against the use

a

in its relations

rules. In

example, the Commission ruled that the Spanish state had given

an unfair advantage to the state company

forcing the

company

in the

to pay back the state for the

mobile phone market,

amount

of the implicit

subsidy the state had given the company.

The

•

control of mergers between firms (for firms with a turnover in excess

of 250 million euros).

Such mergers require prior

mission, and the

Commission has exclusive power

given merger. In

November 2003

merger which would have

book distribution network

ified so as to

for

led the

notification to the

Com-

to approve or prohibit a

example, the Commission rejected a

French firm Lagardere to dominate the

in France; the

terms of the merger had to be mod-

maintain competition in book distribution and thus satisfy the

Commission.

The monitoring

•

15.

of state aid. This

is

another area where the Commission

For further description, see European Commission [2000]. For a description of reforms over

time, see the annual reports from the

[2002].)

European Commission

(for

example European Commission

Future of Europe

17

has exclusive power, and an area where

it

often clashes with governments.

Commission rejected a plan by the French gov-

In 2003 for example, the

ernment to rescue the French firm Alstom, provoking widespread criticism

of Bruxelles in France.

by Bruxelles. Some

fisheries, are

was modified was

until the plan

politically hot sectors,

it

approved

such as agriculture, or coal, or

excluded. But, in general, the rules governing restructuring or

rescue plans are tough:

at the

Not

They can only take the form

normal commercial

rate,

of short-term loans,

and can only be granted once.

These are considerable powers, and the Commission has not hesitated to use

them. 16 This raises two intriguing questions. The

Commission has been so

willing to reform

Commission showed much

less

first

is

why

this part of the

and deregulate, when other parts of the

commitment

to markets.

17

The second

is

why

gov-

ernments have been willing to leave such power in the hands of the Commission.

One hypothesis

to use

is

mandate

its

that this happened partly by accident, that Bruxelles was able

as defined in the Treaty in a

not anticipated. But this hypothesis

is

way

that national governments had

belied by the fact that governments have, at

various times, increased the powers of the Commission in matters of competition

policy. For

example, rules on state aid to airline companies were tightened in 1994,

general rules on rescue plans were tightened in 1999. This suggests an alternative

hypothesis, that governments have willingly delegated those powers to Bruxelles,

in order to achieve reforms, while being able to shift the

point

is

important. As

I

shall argue later,

blame to Bruxelles. This

product and market deregulation put

strong pressures on labor market institutions, raising the risk of reversal.

that Bruxelles, rather than national governments,

is

The

fact

leading the process decreases

this risk.

Does

this

mean

that

all

the reforms of product and financial markets have

from Bruxelles? Obviously

not,

and an important exception

is

come

privatization. But,

16. The Commission publishes an annual "state aid scoreboard", in order to report progress,

show problems, and put pressure on national governments.

17. This is one of the issues taken up in the parallel article by Alesina and Perotti [2004] in this

issue of the Journal.

Future of Europe

been slower, more subject to

there, progress has often

therefore

more country

specific.

The example

political

of France

is

ebbs and flows, and

again revealing here.

Under a

socialist

last rich

country to nationalize a number of banks and firms in the early 1980s.

government, and bucking a general world trend, France was the

The trend then changed

in the late 1980s,

Gaullist government in 1986-1988,

with a

first

wave of privatization under a

and then more steady privatization

under governments both of the right and of the

left.

Despite this

since 1993,

new commitment,

the share of nationalized firms in the business sector remains higher in France than

in other

2.2

European

countries.

Measuring the Changes

How far

has deregulation

more

(or,

in

Regulation

accurately, better regulation) progressed in Eu-

rope? Are there important differences across sectors, across countries?

To answer

these questions requires constructing quantitative measures and indexes, and until

recently,

the gap.

such indexes were missing.

The

Two OECD

and more ambitious one

first

tion of regulation circa 1998;

it is

is

projects have

aimed

now

partially filled

at giving a precise characteriza-

based on the answers from national governments

to a questionaire assessing the status of 1300 regulatory provisions. (The data set

and the construction of the indexes are described

second one

is

more limited

try dimension;

it

three

set,

European

both a time

series

is

The

and a cross coun-

gives the evolution of regulation in seven sectors

1998 (The data set

second data

in scope but has

in Nicoletti et al [1999].)

from 1975 to

described in Nicoletti and Scarpetta [2003].) Based on this

Table 4 gives a sense of the evolutions over time, for the U.S. and

countries, of

two synthetic indexes, the

first

called "barriers to

entrepreneurship" (BE), the second "public ownership" (PO). Each index ranges

from

(no barriers or no public ownership) to

6.

Future of Europe

Table

Indexes of regulation: U.S, France, Germany, the Netherlands.

4.

1975-1998.

PO

BE

1975

1990

1998

1975

1990

1998

U.S.

5.5

2.4

1.5

1.7

1.5

1.5

France

6.0

5.1

3.3

6.0

5.8

4.9

Germany

5.3

4.3

1.9

4.6

3.9

3.0

Netherlands

4.4

5.2

2.3

5.6

5.6

4.0

Table 4 yields three conclusions. First, that regulation has steadily decreased in Europe over time, especially in the 1990s, confirming the informal evidence presented

Second, that Europe

earlier.

is still

more regulated than the U.S. Third,

(this is

less

obvious from the table which gives numbers only for France and Germany,

but

is

clear

when

looking at the whole set of countries) that there

heterogeneity across countries. Regulation

ownership

substantial

high in the Netherlands, public

high in France, for example.

Assessing Structural Changes

2.3

So

still

is still

is

far,

the argument has focused on changes in regulation, not on the economic

outcomes themselves. There

is

plenty of evidence, however, that these changes in

regulation have transformed goods and financial markets.

Consider

ucts have

first

a few macro measures. Prices of specific products or classes of prod-

shown steady

price convergence across countries throughout the 1990s

(European Commission [2002, Annex

change rate

risk has disappeared,

fully converged.

more arms'

liabilities

32%

in

The

and

1].)

.

With the introduction

interest rates

on bonds,

of the Euro, ex-

risk adjusted,

have

structure of financial relations has also changed, becoming

length. For example, the proportion of

bank loans

(based on a sample of large firms) has come

2002 in Germany, and from

75%

to

53%

in firms' financial

down from 74%

in Italy

(Danthine et

in 1990 to

al [2000]).

Future of Europe

The

20

best way, however, to get a sense of the changes that have taken place

look at the evolution of specific sectors. Here, we can rely on a

in particular

in specific sectors in the U.S., Prance,

level

MGI

to

of studies,

two studies conducted by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI),

1997 and 2002. In each of these two studies,

behind the

number

is

in

assessed the levels of productivity

and Germany, and looked

and the evolution of productivity

for the factors

in each country.

shall take

I

three sectors as examples.

Road

•

freight

was traditionally a highly protected and regulated sector

Europe. The internal market, the elimination of restrictions on foreign

ers,

and other reforms have

led to a nearly deregulated market.

indexes suggest that the levels of regulation in France and

ilar

today to those

in the U.S.

(Boylaud

[2000].)

The

Germany

The MGI study

in

carri-

OECD

are sim-

suggests

that labor productivity, which stood in France and

Germany

at roughly

about 85%

in 2000. It

documents

60%

of the U.S. level in 1992, increased to

how changes

in regulation

have allowed

for larger

truck sizes and higher

load rates, leading to higher productivity in both European countries. 18

Uniformization of standards and ownership changes have also transformed

•

The MGI study concludes

the automotive market, especially in France.

that, in the 1990s, France

made up much

of

its

productivity gap relative to

the U.S., with productivity growing at 7.8% in France from 1992 to 2000,

compared to 2.2%

in the U.S.

and Germany.

It

finds that, in turn, this high

productivity growth can be explained by partial privatization of Renault

and the associated change

in governance,

Japanese imports to France

—a

a

crisis at

lifting

and by the

which led

first

quotas of

to financial losses

and

Renault, and then to a successful reorganization.

In the light of the results of the previous section that

•

lifting of

much

of the differ-

ence in productivity growth between the U.S. and Europe can be traced to

the trade sector, retail trade

18.

MGI

is

particularly interesting (another reason

attributes half of the remaining gap to structural factors (geography, which allows for

longer hauls and faster speeds in the US), and half to more recent and

Europe.

is

more limited use

of

IT

in

Future of Europe

that

it

6.8%

21

accounts for a large share of total employment, 8.7% in the U.S.,

because regulation largely takes the form of zon-

in France.) Partly

and these regulations

ing restrictions

some countries remain

fall

outside the Bruxelles mandate,

relatively highly regulated. In France, for example,

two laws, the "Loi Royer" and the "Loi Raffarin" (named

then the minister of commerce,

incumbents a large say

stores,

with predictable

in

now

after its sponsor,

the current prime minister) give local

whether to allow

opening of new large

for the

results.

This would seem to give us a potential key

for

why

productivity levels and

recent productivity growth might be lower in France than in the U.S.

But

the evidence turns out to be more complex:

MGI

The 2002

study finds that labor productivity (measured as gross mar-

gins per hour worked) in 2000

7%

was actually higher by about

food sector in France than in the US.

truncation effects of the higher

19

Once an adjustment

minimum wage

in France,

is

in the retail

made

and

for

hours, productivity appears roughly similar in the two countries.

clusion reached

by

MGI

is

the form of restrictions on

and both more small

French small

new

entry of

medium

size

and more large

size retailers are less efficient

but French large

opening

The

con-

that regulation in France, which mostly takes

hollowing of the size distribution of retailers, with

ers,

for the

size retailers

sized firms, has led to a

less

sized retail-

size retailers (hypermarkets).

than their U.S. counterparts,

turn out to be more

productivity growth over the 1990s, the

medium

MGI

efficient.

study does not find obvious

explanations for the apparently better performance of the US.

of use of

IT does not appear radically

equal to

8%

of gross margins in the

Turning to

different; in 1999,

US, versus 6.3%

in

The degree

spending on IT was

France and 6.0% in

Germany.

This leads one groping

19.

The 1997 study also

make construction

prices

proxy measure

for

an explanation of the apparently different evo-

TFP. Arguing that large differences in land

comparable capital stocks unreliable, it uses square footage as a

constructs measures of

of

for capital. Results are quite similar to

those for labor productivity.

Future of Europe

22

lutions of productivity in retail trade in the U.S.

A

tentative explanation

find that, in the U.S.,

and Europe

based on the findings of Foster

is

most of the productivity growth

the 1990s can be attributed to composition effects,

productive by more productive establishments.

less

not exist for France, but the evidence

limited the

amount

of

new

that

lar,

it

who

,

in retail trade in

i.e.

the replacement of

A

similar study does

that regulation has indeed sharply

firms.

20

may be

limiting productivity growth

(An argument against

this hypothesis

is

does not obviously extend to other European countries. In particu-

productivity growth appears to have been low in retail trade in the

in the 1990s

trade sector.

The MGI

et al [2002]

permits, especially since the tightening of zoning

restrictions in 1996. Thus, regulation

by restricting turnover of

is

in the 1990s.

(Basu

et al [2003]), a

country with low regulation of the

UK

retail

21

)

studies cover a

number

of other sectors, from fixed

munications to electricity generation and distribution, to

and mobile telecom-

retail

banking. In most

of these sectors, deregulation (or appropriate regulation, as in the case of telecom-

munications) appears to have had important effects on the behavior of firms, the

degree of competition, and the level of productivity. This however brings a puzzle:

Why

tivity

hasn't this transformation, so apparent on the ground, led to higher produc-

growth

in the

1990s? Measurement issues, in particular for price deflators,

the representativeness of the sectors chosen by

to

end

this section

play a role.

I

want

unemployment and low employment growth, many govern-

ments endorsed the idea of "job

fallacy,

rich growth".

The

idea,

a direct descendant of

was based on the idea that output growth was given,

and so low productivity growth would allow

20.

all

however with another, tentative, hypothesis. Throughout the

1990s, faced with high

the lump-of-labor

MGI, may

for

more employment growth. 22 More

Bertrand and Kramarz [2002] look at the related question of whether these restrictions have

hindered employment growth, and conclude that they have.

21.

I

Comparisons are plagued by problems

in Kites ol

prod lie tivitj growth

Van Ark, presented

22.

A

in

in

retail

of definition

(Yum Basil

et

al

and measurement. For example, the

are

aibst ant iall\

luwei

than

I

hose

es-

1mm

the previous section.

"success story" here

is

Spain, where, despite moderate output growth, dismal productivity

Future of Europe

23

generally, firms were under considerable pressure to maintain

low

demand growth,

which might lead to

many

this

employment. Given

reduced the incentives of firms to implement innovations

layoffs or plant closings.

Thus, a tentative hypothesis

is

that

innovations were not implemented, leading to lower productivity growth. 23

weakness of the hypothesis

that the channels through which government pressure

is

was applied on firms are not easy to

rect, it is

good news

identify.

for the future, as

so will implementation,

and

A

it

24

But,

if

the hypothesis

suggests that,

if

is

partly cor-

output growth increases,

in turn productivity growth.

Implications for Labor Markets.

3

Jacques Delors wanted the "Single Market" report to include a "social chapter,"

a

set of rules for the labor

market.

He

did not succeed.

And

to a large extent,

reforms in the product and financial markets have shaped labor market changes

and labor market reforms since then. This

at past evolutions,

is

the focus of this section, looking both

and what may lay down the road.

Deregulation in Goods and Financial Markets, Wages, and

3.1

Unemployment

Higher goods market competition increases average real wages, and

decrease unemployment. Let

chard and Giavazzi

[2003], as

me

it

briefly

lays the

is

likely to

go through the argument, following Blan-

ground

for the discussion

which

follows.

25

growth has allowed

23.

for a substantial reduction of unemployment.

Informal evidence from interviews of firms' managers suggest that they believe that, absent

political

so

24.

and

social constraints, they could

and would reduce employment further than they have

far.

One may

think of testing this hypothesis by looking across sectors and countries.

find that, ceteris paribus, sectors that

had higher demand

for

One should

exogenous reasons also have had

I have not explored this.

Blanchard and Giavazzi study the effect of different dimensions of product market deregulation in a model with monopolistic competition in the goods market, and different forms of

collective bargaining in the labor market. An extension to include capital accumulation is given

higher productivity growth.

25.

Future of Europe

Consider

first

24

the case where the wage

is

allocative,

i.e.

the case where firms take

the wage as given in setting prices. Then, an increase in competition will lead

firms to choose a lower markup, leading to a decrease in prices given wages.

Put

another way, higher competition will lead to a higher real wage at any given level

of

employment. Given any positively sloping labor supply or "wage curve",

will lead, in turn, to

an increase

in the real

Consider instead the case where the wage

is

wage and an increase

distributive, a case

in

this

employment.

known

as "efficient

bargaining" in the labor literature. In this case, firms choose prices not based on

the wage but on the reservation wage of workers.

The wage

itself is

as to divide the total rents, according to the relative bargaining

and

its

of an increase in competition,

thus eliminates

all

monopoly

monopoly power, but

is

which eliminates monopoly power, and

rents (the argument holds for a partial reduction of

easier to state this way).

work: As workers, workers

lose.

so they end up better

More

off.

There are then two

effects at

But, as consumers, they gain, and they gain more,

explicitly:

Consider a given firm. The increase in competition leads to lower prices,

eliminating monopoly rents.

As

part of these rents were accruing to the

workers, this effect makes the workers in this firm worse

•

power of the firm

workers. 26

Think now

•

then chosen so

To the

off.

extent, however, that the increase in competition affects

the economy, this means that

all

prices are

now

lower,

all

and the rents which

were previously going to firms and workers now go to consumers

form of lower

prices).

firms in

Thus, as consumers, workers gain.

And

(in

the

because they

by Spector [2004]. An interesting alternative treatment, which assumes Cournot competition in

the goods market, and firm-level collective bargaining in a search labor market is developed by

Ebell and Haefke [2003].

26. The question of how much of the rents workers appropriate is an old question in labor economics. A study of the relation between wage differentials and the indexes of regulation described

earlier, across European countries and sectors by Nicoletti and Jean [2002] finds a significant

effect on wages in manufacturing, a less significant effect outside of manufacturing. The authors

hypothesize that some of the rents are taken in forms other than wages, such as lower effort and

productivity or restrictions on employment.

Future of Europe

now

get

all

25

the rents, whereas before, as workers, they were only getting a

fraction of them, their real

These conclusions

raise

wage

an obvious

higher,

is

and they are better

product market deregulation, and by

issue: If

implication, higher competition, increases real wages

why do

If

workers so often oppose

the degree of monopoly power

then

all

is

workers are indeed better

(the lost portion of rents)

is

it?

a general equilibrium

The degree

effect,

while the benefit (the decrease in prices)

effect,

which may be much

is

wage

increases, but

some workers

of trade liberalization, those

diffuse.

The

implication

is

who

lose

lose,

not in others, workers in those firms will

is

better

off,

tensions. This

by Bruxelles

is

is

where the

fact that

much

of high relevance. Strikes

As

it is still

is

are losing, while gains are

some

Thus, even

likely to

if

is

more

in doubt.

progress of reform in the public sector.

We

have so

far

and

generate strikes and social

is

driven

lead to disruptions, but are unlikely

The main example

is

here

not driven

is

the slow

28

focused on product market deregulation.

market deregulation are

firms,

of product market deregulation

may

more

the average worker

to stop the reform process. However, for sectors where deregulation

by Bruxelles, the outcome

is

true that the average

rents are reduced in

lose.

product market deregulation

27

while others gain. And, as in the case

know they

straightforward.

less salient.

not the same across sectors, nor

deregulation uniform across the board. In this case,

real

uniformly reduced,

is

But, even in this case, the cost to the worker

monopoly power however

of

actually gives us a key:

the same to start with, and

a direct

is

and decreases unemployment,

The argument above

off.

off.

slightly different.

One can think

The

effects of financial

of financial

ulation as increasing the elasticity of capital to the rate of return

to a sector, or to a country. Deregulation

may

market dereg-

—be

it

to a firm,

then require a decrease in the real

wage.

27.

This argument

28.

An

is

Gersbach [2003].

problems of reform of the French public sector

close to that developed in

insightful analysis of the

by the Institut Montaigne

[2003]

is

given in a study

Future of Europe

26

Think

for

owned

firms as being inelastic:

example of privatization.

continue to invest.

of return,

and

If

the firm

turn

this in

It is

Even if the

is

may

reasonable to think of capital in statefirm

is

making

privatized, capital will

losses,

now

may often

the state

require the market rate

require a decrease in the real wage.

The same may

hold for a country as a whole. Limits on international capital mobility

may

allow

labor to extract a higher real wage, and thus a lower return to capital, without

suffering capital flight. Higher financial integration will then require a decrease

in the real wage. If unions

do not

realize the

not change their behavior, then the effect

lower employment for

How much

some period

of the evolution of

be explained by deregulation

topics of research (see for

answer

is

is

may be

lower capital accumulation, and

of time.

wages and unemployment over the recent past can

in

goods and labor markets

example Blanchard and Philippon

that deregulation

may

more recent and more limited

section

change in the environment, and do

well account for

fall in

in

my

one of

[2003]).

some of the

unemployment

however more on the implications

is

The

current

tentative

earlier rise,

and the

Europe. The focus of this

for the labor

market

in general,

the behavior of unions and the reform of labor institutions in particular.

turn to those

I

and

now

issues.

Weaker and Smarter Unions

3.2

Deregulation implies smaller rents. Smaller rents imply smaller benefits

from joining a union. This in turn suggests a decrease

in

for

workers

membership, a decrease

in

the power of unions. These implications are indeed consistent with the facts. Union

membership has generally declined

22%

in

1980 to 10%

(Boeri et

al [2001]).

in 1998,

all

and from 36%

such as the decline

played a

role.

explain only part of the decline:

residual.

Europe, going

in

A

in

for

1990 to

This decline in membership

in rents; other factors,

time work, have

in

is

example

26%

in

France from

in 1998 in

Germany

only partly due to the decline

manufacturing, the increase in part

But econometric evidence suggests that they

decline in rents

is

a plausible candidate for the

Future of Europe

27

Interestingly, there has

been no decline

membership

in

Union membership has increased from 78%

from 69% to 79%

less

To

of

in

in

in

1980 and to

Scandinavian countries.

88%

in

Denmark, two countries where unions have

1998 in Sweden,

traditionally been

confrontational than in the rest of Europe. This leads to the next point.

European unions

caricature slightly, the rhetoric of

two forms: Some unions speak of the need

While fighting

capital."

for labor,

an adequate rate of return

suffer.

29

Some unions

for

for capital, lest capital

much

insist

and

in one

on the need to maintain

move away and employment

closer to the old "class struggle"

view of relations between capital and labor. They speak as

distribution of income between wages

comes

a "partnership between labor and

they nevertheless

instead have a view

traditionally

profits

were a

if

the fight over the

fight for rents,

with few

implications for employment.

In a world of high rents and low capital mobility, the second view had

But the decline

fication.

for labor

we argue

rhetoric

for

make

it

it

took some time,

their attitudes

example the case

two main unions

and the increase

in the elasticity of the

justi-

demand

a dangerous strategy toda}'. In Blanchard and Philippon [2003],

that, while

and

of rents

some

for

many unions have indeed

shifted their

— although at different speeds across countries. This

unions in the

in France.

30

UK,

or for

example

is

CFDT, one of the

CGT, the other main

for the

Others however, such as the

French union, have not changed their rhetoric very much. One interpretation

is

that those unions have decided to focus on the public sector, where rent extraction

remains easier than in the private sector. (The membership of the

primarily in the public sector). But

it is

CGT

is

now

reasonable to conclude that, in general,

unions have become both weaker and smarter.

Perhaps the best-known early statement along these lines is by Helmut Schmidt, then the

Germany, in 1976: "The profits of enterprises today are the

investments of tomorrow, and the investments of tomorrow are the jobs of the day after"

30. An ironic and revealing anecdote: In November 2003, Denis MacShane, Britain's minister for

Europe and a former senior trade union official, admonished German unions for their opposition

to Chancellor Gerard Schroder's reform program, "Agenda 2010", telling them that there were

"out of touch with modernity" (Financial Times, November 19, 2003).

29.

Social Democratic Chancellor of

Future of Europe

28

3.3

Reforms of Labor Market Institutions

What

have been, and are

likely to be, the effects of

product and financial market

deregulation on labor market institutions, from unemployment insurance, to the

minimum

wage, to employment protection? This

and empirical research needs to be done. But the following approach

theoretical

seems

useful.

market

There are two broad approaches to thinking about the shape of labor

institutions:

The

•

a hard question, and more

is

first is

that these institutions are yet another

tribution of rents between firms

of workers, or

esting. It plots the degree of

OECD,

between

31

different

groups

In this context, Figure

in Nicoletti et al [2000],

employment

to affect the dis-

is

particularly inter-

protection, as constructed

by the

versus an index of product market regulation, also constructed by

OECD

the

(or

between workers and non workers).

reproduced from Figure 14

1,

and workers

way

based on the large regulatory data

section, across

most

OECD

set described in the previous

countries in the late 1990s.

It

shows the strong

positive correlation between product market regulation and

employment

protection.

The second

•

is

that these institutions are put in place to solve a

market imperfections,

for

example the

failure of

number

of

markets to provide adequate

unemployment insurance.

The

first

naive,

approach, on

and both

about the

Think

in

own,

is

too cynical.

The

sets of factors surely play a role.

effects of

first

its

second, on

its

own

again,

is

too

This gives us a way of thinking

goods and financial markets deregulation.

terms of rent distribution. To the extent that rents are now smaller,

labor market institutions, thought of as distorting instruments to extract rents,

are

now

bership

31.

who

less attractive (this

is

likely to decrease)

argument

.

A

parallels the

argument

particularly egregious

for

why union mem-

example of rent extraction

See Saint-Paul [2000] for a development of this approach. See also Bertola and Boeri [2003],

analyze the effects of product market deregulation in such a context.

Employment

*t.u

-

3.5

-

protection legislation

Portugal

Greece

Italy

AcSpam

3.0

France

-

Norway

Germany

Japan

2.5

-

Sweden

a

• Austria

.

i^Jetherlands

Finland

2.0

-

1.5

-

Belgium

Denmark

Switzerland

1.0

-

0.5

-

New

Ireland

Zealand

Canada

United Kingdom

United States

on

-

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

Product market regulation

Figure 4

Product market regulation and employment protection legislation (from Nicoletti

et al, 1999)

Future of Europe

in this context

is

29

the unemployment insurance system in place in France for peo-

and the performing

ple involved in theater, movies,

du

arts (in French, "intermittents

spectacle"). Until this year, this unusually generous

unemployment insurance

guaranteed up to 12 months of unemployment for anyone

equivalent of 3

months

in the previous year.

Not

who had worked

surprisingly, this

large deficit. This could be seen as reflecting the often stated

French government to help and subsidize culture, except

is

the