Document 11163186

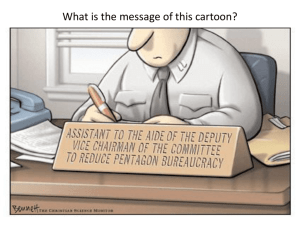

advertisement

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/propertyrightscoOOacem

DEWEY

HB31

.M415

1

I

working paper

department

of economics

PROPERTY RIGHTS, CORRUPT/ON AND THE ALLOCATION

OF TALENT: A GENERAL EQU/L/BR/UM APPROACH

Daron Acemoglu

Thierry Verdier

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass. 02139

PROPERTY RIGHTS. CORRUPTION AND THE ALLOCATION

OF TALENT: A GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM APPROACH

Daron Acemoglu

Thierry Verdier

96-5

Jan.

1996

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

iViAR

IS 1996

PROPERTY RIGHTS, CORRUPTION AND

THE ALLOCATION OF TALENT: A GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM APPROACH

Daron Acemoglu

MIT

and

Thierry Verdier

CERAS and DELTA

First Version: January 1994

Current Version: January 1996

JEL

Keywords: Property

We are grateful to Olivier Blanchard,

Piketty,

Classification:

NYU

Political

Law

Enforcement, Development.

Kremer, Thomas

MIT, Northwestern, Paris,

Abhijit Banerjee, Ricardo Caballero, Michael

Jim Robinson, Christian Schulz and seminar

Brussels and

D23, H40

Rights, Corruption, Allocation of Talent,

Economy Conference

participants at

for useful

comments.

PROPERTY RIGHTS, CORRUPTION AND

THE ALLOCATION OF TALENT: A GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM APPROACH

JEL

Keywords: Property

Classification:

D23, H40

Rights, Corruption, Allocation of Talent,

Law

Enforcement, Development.

Abstract

We

consider an economy where property rights are necessary to ensure sufficient rewards

to ex ante investments. Because enforcement of property rights influences the ex post distribution

of rents, there is room for corruption. We characterize the optimal organization of the society and

optimal degree of property right enforcement subject to incentive constraints of the agents. We find

that three frequently mentioned government failures arise quite naturally as part of the optimal

mechanism; (i) rents for government employees, (ii) corruption, and (iii) misallocation of talent.

Therefore, these observations are not in themselves proof of government failure. We also discover

that the general equilibrium aspect of our model leads to a number of new results: there may exist

a "free-lunch" such that over a certain range it is possible to simultaneously reduce corruption,

misallocation of talent and increase investments; and it will often be the case that bureaucracies will

impose a certain amount of

self-discipline.

"What distinguishes property from mere momentary possession

be enforced by society or the

"A coercive third-party

is

state,

by custom or convention or law.

essential to constrain the parties to

impersonal exchange with other." D. North [1991,

more

will

be bought

enforcement

I.

is less

if the statute

expensive."

a claim that

will

C. B. Macpherson [1978]

"

exchange when the contracts essential

p. 194].

buys the amount of enforcement which

society...

is

of modern technology extend across time and space and involve

to realizing the productive potential

"The

that property

is

serves a

it

deems appropriate

more valuable

goal...

and

to the statute

if

or rule:

a given increase

in

G. Becker and G. Stigler [1974, p. 3].

Introduction

many economists and

Despite prevalent market failures,

government intervention

social

scientists

are

wary of

and Vishny [1994]). Three concerns, often

(e.g. Mills [1986], Shleifer

suggested as arguments in support of limited government, are:

1)

Governments pay excessive

salaries (rents) to their

studies using U.S. data (e.g. Katz

employees. This claim receives support from

and Kruger [1991], Poterba and Ruben [1994]) as well as casual

empiricism from developing countries.

2)

Government

empiricism

3)

(e.g.

Government

(e.g.

intervention brings corruption. Case studies of bureaucratic corruption and casual

Mydral [1986], Carino [1986], DeSoto [1989]) support

this

argument.

intervention distorts the allocation of resources, in particular the allocation of talent

Lai [1985], Donahue [1989]). There are

many

stories of talented

especially in developing countries, entering the civil service only to

Are these concerns

need not be real failures

justified? In this

at all:

even

in

its

paper

we

most basic

sit at

young men and women,

unproductive desk jobs.

argue that these three 'failures' of the

role as the protector of property rights, the

implementation of the government's duties will lead to the presence of rents for

to corruption,

and

to misallocation of resources.

state

many

bureaucrats,

However, these are not proof of government

failure

but signs of the tight incentive constraints that even the simplest form of government intervention

has to live with.

Although our model can be extended

of property rights

is

to other (useful) roles of the

the least controversial role of the state accepted

diverse as David Himie, Karl

Marx and Robert Nozick. Moreover,

it

government, the protection

by

is

political

because economic agents

trust that the state will enforce their claims that they undertake long-term investments

wealth.

The importance of secure property

emphasized

(e.g.

and accumulate

development process has also been repeatedly

Mydral [1986], North and Thomas [1973]). For

that the lack of transfer of wealth

we

rights in the

philosophers as

between generations, which

is

instance, Braudel [1977] argues

a limitation on property rights as

understand them today, was one of the key reasons for the lack of accumulation incentives in

Eastern societies.

An understanding

of the role and duties of the government requires an analysis of (1) the cost

of government action as emphasized by Becker and Stigler [1974], and the incentives of government

employees as emphasized by the

economy

considerations take us to an

More

enforce property rights.

in

reports

upon which

this

is

engage

How

in practice,

in.

way

These

in the public sector to

employees ("bureaucrats")' inspect

bilateral

the compensation of the parties in this business

report

will

that

is

ex ante anticipation of an appropriate

be influence

room

In other words, there will be

undertake productive

to

activities that

entrepreneurs would

for corruption.

can the honesty of bureaucrats be ensured? Although there are a number of methods

many of these

for taking bribes (e.g.

simple

work

to

[1975]).

that since the report of the bureaucrat will influence the

ex post distribution of income and rents, there

like to

Rose-Ackerman

an appropriate reward scheme, will encourage entrepreneurs

The key problem however

investments.

(e.g.

which some agents choose

venture will be based. The importance of

report, thus of

on corruption

specifically, public sector

make

business parmerships and

literature

involve increasing the attractiveness of the job while imposing punishments

Rose-Ackerman [1975], Besley and McLaren

as an "efficiency

important cost; since there

is

wage"

for the bureaucrats.

a "rent"

m one of the

However,

sectors of this

[1993]).

We

model

this in a

immediately introduces an

this

economy,

the allocation of talent

does not take place according to the comparative advantage principle, thus the efficiency wage

induces a misallocation of talent. Moreover, given that the prevention of corruption

terms of leading to a misallocation of resources),

completely. Thus, our

first

and key result

involve a government sector whose role

private exchange. But

more

is

is

it

will often not

be optimal

costly (in

to prevent corruption

economy

that the optimal organization of the

to protect property rights

is

will

and to set the ground rules for

importantly, in this optimal organization of the society, there will be

corruption, rents for government employees and misallocation of talent. At this point,

it is

useful to

contrast our key result to an intuition dating at least back to Leff [1964] which claims that corruption

is

not a proof of market failure, but instead a sign of markets circumventing the

erected by governments.

corruption

is

an

Our conclusion could not be more

evil that the society has to put

government intervention

in the

the historical accounts of

up with

artificial barriers

different than Leffs: in our

in order to benefit

most economical way. This conclusion

government intervention. For instance

is

from necessary

also in line with

Wade

economy

some of

[1990] documents the

problems of government intervention but also stresses the importance of such intervention for East

Asian Development.

In addition to this main conclusion,

1)

An

'

we draw

important issue occupying the minds of,

Throughout the paper we

will use public sector

believe that enforcing property rights

is

a

number of further

among

others, Locke,

insights

Hume

from our

analysis:

and Rousseau

employee interchangeably with bureaucrat. This

is

is

not because

the

we

bureaucrats main role. Rather, this terminology facilitates the exposition and also

stresses that other roles of bureaucrats in practice often involve ex post redistribution

and thus similar issues

arise.

degree of just or optimal property rights. Our analysis, following Becker and Stigler, takes an

On

economist's approach by emphasizing the costs and benefits of property rights enforcement.

the

cost side, government interventions have to ensure the honesty of the agents responsible for enforcing

On

these property rights.

the benefit side, property rights provide incentives for a better allocation

we show

of resources. In contrast to Becker and Stigler, however,

interactions are important in this process,

and also

general equilibrium

that

because property rights not only provide

that

incentives but also distribute rents, the degree of property rights enforcement that arises as the result

of political equilibrium

2)

We

may

from

differ

the optimal amount.

also discover that the size of corporate relative to non-corporate sector

of the degree of optimal and equilibrium enforcement. This

correlation between the development level of an

is

economy and

a key determinant

is

an important observation because a

the degree of property rights

noted, both in the cross-section and time-series. For instance, in Mauro's [1995] empirical

index of corruption

shows

that

is

found

to

growth and negatively correlated with

Mydral

between

[1968]).

rights cannot develop?

Do

Our

work an

positively correlated with investment

is

political instability. Further,

Alesina et

al

and

[1992] document

and growth, and many scholars of development

political instability

blame underdevelopment partly on weak property

[1973],

often

be negatively correlated with investment and growth, Svensson [1994]

an index of property rights enforcement

the negative correlation

is

rights

and corruption

(e.g.

these correlations arise because societies that

analysis suggests that the reverse causality

is

North and Thomas

do not enforce property

a factor to be taken into

account^; economies with less productive investment opportunities will tend to choose a lower level

of property rights enforcement (which then of course reduces investment incentives further).

3)

An

obstacle to efficient government

organization of the society

power

to look after their

is

that in contrast to

somehow implemented, government

is

own

the influence of bureaucracies

interest (e.g. Shleifer

on

naturally impose

explanation for

when

have the

the set of the rules they face). This could be one of the

discipline

major

However, a simple extension of our model

bureaucrats have the power to look after their

some degree of

why

officials in general will

and Vishny [1993]; also see Wilson [1989] on

arguments in favor of limiting the size of government.

demonstrates that even

our simple story where the optimal

on themselves. Further,

this

own

interest, they will

observation suggests an

bureaucracies, for instance the French [Crozier, 1956] or

many

Latin American

organizations [Sloan, 1989], have rigid structures and a variety of codes that reduce discretion of

^ It

is

natural to ask then whether this reverse causality

means

that the often

made

assertions that corruption (e.g.

Klitgaard [1988] or Mydral [1968]) or low levels of property rights (Rosenberg and Bridzell [1968])

development of an economy are incorrect. The answer

economy may

Acemoglu [1995];

equivalent of our

is

similar to

the future

request.

which

is

no.

An

earlier version of our

get stuck in a high corruption and low property rights equilibria.

anticipating

low propeny

in turn contaminates future investment

rights, agents invest less

and

may jeopardize the

how a dynamic

paper showed

The

intuition of this result

and thus support low property rights

political decisions. Details available

in

from the authors upon

individual bureaucrats.

Finally, although the basic intuition underlying our

argument

equilibrium model to formalize our claims. However, this analysis

First, this places

us

among

Acemoglu and

simple,

we use

also not without

is

a general

rewards.

its

the papers that emphasize the determination of organizational relations

in a general equilibrium context (to

[1995],

is

name

a few, Banerjee and

Zilibotti [1995]), but with a

Newman

[1993], Legros and

Newman

very different scope. Second, our analysis enables

us to distinguish clearly between two distinct constraints on the enforcement of property rights:

the

number of bureaucrats;

(ii)

interesting implications. Third,

increase in the public sector

of

and which one of these constraints

their honesty;

we

wage

discover a general equilibrium ^ee-/Mnc/z effect;

rate not only reduces corruption but also

more severe has

we show

that

an

improves the allocation

This happens because an increase in the public sector wage prevents corruption and makes

talent.

investment more profitable for the entrepreneurs, thus the private sector

attractive relative to the public sector. This

is

may become

by many developing countries

sufficiently

an important observation since the emphasis on the

costs of government intervention and the increasingly severe fiscal constraints,

reaction

is

(i)

may have

led

an over-

in cutting public sector salaries. In particular, in a recent

paper, Klitgaard [1993] argues that there

is

"incentive

myopia"

countries because bureaucrats are badly selected and paid too

in

little

free-lunch effect suggests that increasing the pay of bureaucrats

government sectors of many

do

to

their jobs properly.

may be

less costly than

it

Our

first

appears.

There

is

only limited work on the determination of property rights, corruption and allocation

of talent in an equilibrium framework. In

this respect

our paper

is

definitely related to the principal-

agent approach to law enforcement pioneered by Becker [1968] and Stigler [1970], for recent

contributions, see Besley and

partial equilibrium nature

in

McLaren [1993] and

Carrillo [1995].

However,

in contrast to the

of these papers which take the costs and benefits as exogenously given,

our model these are derived endogenously. Banerjee's [1994] model of bribes, though again partial

equilibrium,

also related; bureaucrats accept bribes because they have a different utility fimction

is

than that of the government which

is

trying to implement an allocation that does not

revenues. In Banerjee's model, as in ours, corruption

may be an

maximize

unavoidable price to pay for the

implementation of certain allocations.

Finally, our paper is also linked to the rapidly

our result with

this literature is

a good

growing

literature

on rent-seeking. Contrasting

way of emphasizing some of our key

intuitions.

The

rent-

seeking literature stresses the conflicts between different groups in society in dividing the rents (see

Tomell [1993], Acemoglu [1995],

a group

-

like

bureaucracy or

(see Mills [1986] or

Hirshleifer [1995] for recent contributions). In

elites - is

many

instances,

argued to be in dire conflict with the rest of the population

Olson [1991] for statements along these

and Verdier [1994] for economic models). In our economy

lines, or

too, a

Grossman [1991] and Ades

group of agents, the bureaucrats.

become

the ex post "rent-seekers".

However, our paper

differs

from

this hterature in that

investigate the microfoundations, and the general equihbrium interactions

and a number of very

different insights arise. First, as noted above, although bureaucrats act as rent-seekers

corrupt, their existence

is

conflict

between

and are often

necessary to solve more important market failures. Second, although there

is

the bureaucrats

among

important conflicts

we

and the entrepreneurs

in the distribution of rents, there are also

entrepreneurs themselves, and despite

all

these conflicts the general

equilibrium interactions imply that interests of different groups can be aligned in certain simations,

i.e.

our free lunch

effect.

And

finally,

our result in section VII shows that the bureaucrats, as a

group, will often prefer to impose discipline on themselves, thus reducing the amount of social

conflict.

The plan of

the paper

as follows. Section

is

II

outlines the basic

framework. Section

derives the equilibrium allocations, corruption and investment levels for given public sector

rate.

Sector

economy

IV derives

III

wage

and the optimal organization of the

the optimal degree of property rights

subject to the incentive constraints. This section demonstrates that rents for public sector

employees and misallocation of

talent will

be part of the optimal organization. However, under the

parameter configurations of section IV, corruption never arises as part of the optimal mechanism.

Section

V

shows

that in a different region of the

parameter space, the optimal organization will

exhibit corruption as well as rents and misallocation of talent.

equilibriimi. Section VII suggests

how

Section VI turns to political

bureaucratic self-control can be endogenized. Finally, section

VIII concludes while an appendix contains

all

the proofs.

n. The Model

Our economy

consists of a

Each agent can enter one of

the

continuum of risk-neutral agents, with measure normalized

two occupations

in this

economy; entrepreneurship or the public

sector. Production takes place in the private sector of this

necessary to enforce property rights. Agents in

this

economy but

economy

the public sector will be

are differentiated by their level of

a=0

entrepreneurial talent (or comparative advantage), a, with the convention that

most

talented agent.

The

to 1.

level of talent is uniformly distributed over [0, 1]

and

is

represents the

assumed

to

be the

private information of each agent.

The entrepreneurial sector

To

enter entrepreneurship, each agent has to incur the cost of

C(a). For simplicity

we

will consider the linear case C(a)

=

a.

human

Production in

capital investment,

this

economy

takes

place in pairs of entrepreneurs randomly matched. There are two complementary functions in a

project: Production, P,

and Marketing,

M.

After a pair

randomly allocated between the entrepreneurs. After

this

is

formed, these two functions are also

assignment, the production entrepreneur

has an additional investment decision which costs

denoted by

If

is

V^Vq and

project

V takes

the value V^ while if he has

with probability q, V=Vj.

realized value

its

is

We

assume

made

that

the investment, with probability (1-

q(V,-VQ)

>

e,

so the ex ante investment

(socially) profitable.

Whether

An

the production entrepreneur invests or not will

depend on the returns he expects.

optimal contract would pay a fixed return to the marketing entrepreneur and

M would receive R

claimant thus inducing the right investment incentives. Thus

the rest^, V-R.

is

run and

is

This value depends on whether the production entrepreneur, P, has invested or not.

V.

he has not invested,

q),

The

e.

However,

there

is

one problem with

only observed by the marketing entrepreneur,

V= Vq

that

this contract; in

M, and

never

invest

the residual

(<Vq) while P gets

our economy,

V accrues

to

and

he will therefore have an incentive to claim

and keep the difference when the project has a higher return. As a

entrepreneur will

make P

result, the

and socially beneficial investment opportunities

unexploited. But the introduction of a public sector helps by ensuring that

production

will

remain

M reports truthfully and

thus enforcing property rights^.

The public sector

Agents can enter the public sector

More

enforce property rights.

no cost

at

specifically,

and observes the realization of the return.

[a normalization]

each bureaucrat

He can

consider the situation in which

M,

V= Vy;

if

will

we

will

VG

{Vq, V,}

and conditional upon

has to pay V-R to the production entrepreneurs, P.

the bureaucrat reports Vg instead of V/,

assume for simplicity

to

matched with a pair of entrepreneurs

that

whenever there

is

this

Now

M would gain V,-Vg,

thus will have an incentive to offer part of this return to the bureaucrat and induce

In what follows

be employed

consequently enforce the appropriate payments

between the two entrepreneurs. He would report a value of

report the marketing entrepreneur,

is

and they

him

to misreport.

corruption (bribery)

all

the

benefits accrue to the bureaucrat, thus the bribe will be equal to Vj-Vg^.

^

when

We assume that such a contract can be written and committed to.

the entrepreneurs

Parenthetically, there

is

an interesting effect that

For

instance, this contract can be written at the point

made. Alternatively, such a contract may be specified by law.

we are ignoring; the agents may choose a contract that reduces the bribes

meet but before the assignment

is

that the bureaucrat can receive.

^ It is worth emphasizing that since the

outcome of the project

the bureaucrats, there

is

no contract

of the private agents.

It

could also be argued that the role

that

is

can induce investment. Thus

we

not observed by the production entrepreneur, without

we

are not articifically restricting the contract space

assign to the public sector can be played by a collection of

Given the set-up of our model this is certainly possible. In this however the equilibrium would depend on the

market structure and entry conditions for this sector, and in general the constrained optimum will not be reached.

private agents.

5

We

assume

that only

bureaucrat over-report. This

M

is

offers bribes

and thus

natural because

P does

V

will only

be under- reported; P never offers bribes to make the

not observe the actual realization, and under our assumption that the

all the bargaining power in the bribe game, P will prefer not to offer bribes and hope for an honest bureaucrat

and V=V,. Further, given our assumptions, at the time of the bribe, the entrepreneur will have no funds and the bribe will

have to be paid ex post which will introduce reverse hold up problems. In any case, allowing for this would not change our

bureaucrat has

6

However, two forces mitigate

probability

problem of corruption.

the

of getting caught in which case he loses

/J

of getting caught, p,

administrative control

as a self-discipline

first

is

mechanism of

T

magnitude of

this cost is

(This

each bureaucrat

is

money. This probability

We

will

endogenize

this probability in section

assumed

VII

"moral cost", e.g. Klitgaard [1988]). The exact

to as

discovered only after being in the bureaucracy^ and

for a proportion

possible values:

bribe

the bureaucracy. Second, corrupt bureaucrats incur a dishonesty

sometimes referred

is

wage and

each bureaucrat has a

taken as an exogenous parameter capturing the degree of severity of

on bureaucratic corruption.

cost equal to

all his

First,

a of bureaucrats, and 7

to extract the

is

supposed

to take

two

for a proportion 1-a. In particular, since

whole surplus, when he meets a pair of entrepreneurs with

a successful investment, he will accept bribes provided that:

W-T<

W

where

[W-T^{V,-V^)]{\-p) - r

wage

the gross public sector's

is

the dishonesty cost and

non-observable and

p

it is

is

(1)

T

rate,

is

the

lump-sum

the probability of being caught

when

therefore not possible to pay differential

that the important variable for the bureaucrat

is

tax imposed

dishonest.

It is

agents,

F

is

important that

T

is

on

all

wages conditional on F. Note also

W-T, the gross wage

minus the tax

rate

rate. If

caught taking bribes, he loses the wage rate but also does not pay taxes since he has no money.

Given

this

form,

we can define w=W-T,

the net

wage of bureaucrats and carry out our

analysis with

this variable''.

Let us

"/

=

According

now

define

(VrVo) (1-P)/P -lip and «„

to equation (1),

Uq, only the fraction

w,

when w <

= (Vr^^

(l-p)/P-

w,, all bureaucrats are ready to be corrupt;

a of bureaucrats with no dishonesty

when

cost will accept bribes; finally

u>j

< w <

when wq

<

bureaucrats will be honest.

all

Allocation of Talent:

Let

be the size of the bureaucracy. Since one bureaucrat per project

Ig

property rights and two entrepreneurs are necessary to run a project,

bureaucracy

results.

Ig

> 1/3 means more

Also note that the assumption

bureaucrats than the

number of

it

is

is

sufficient to enforce

clear that a size of the

projects to be monitored, thus

that the bureaucrat receives all the surplus as the bribe just simplifies the notation but

does not affect our results.

^

This assumption enables us to ignore the adverse selection problem. Without

this

assumption, dishonest people would

be more willing to apply to public sector jobs (e.g. Besley and McLaren [1993]). However, if we were to allow for this

effect, it would also be necessary to introduce the possibility that some honest agents would be keen to become a bureaucrat

because of non-pecuniary reasons.

"^

This emphasizes that

we

could have made the alternative assumption that only entrepreneurs pay taxes and bureaucrats

w

and obtain exactly the same expressions and results. Another alternative which would not change our results but

complicate our expressions is for the government to only pay bureaucrats who have matched with a pair of entrepreneurs or

are paid

to

make

the bureaucrats salary conditional

on

his report.

wages are paid

in

many

real

assume

to socially useless bureaucrats.

economies

While

many people may

the bureaucracy, too

rate,

no additional wealth

application fee,

a result, the

talent.

problem and

in this

i.e. sells

hiring decisions

a result of this restriction

on

is

is

on

the size of

not publicly observed becomes important.

still later

The

the talent of the applicants [and since agents have

economy, screening mechanisms

the jobs, but

government

who do

its

As

apply to the public sector for certain levels of the public

w. Here our assumption that talent

government cannot condition

individuals

this

/g<i/J. This will help us concentrate on the determinants of the trade-off between

that

wage

important source of inefficiency

and Vishny, 1994], here we abstract from

[e.g. Shleifer

property rights enforcement and the allocation of

sector

may be an

this

in

which

the

government charges an

pays an efficiency wage are not implementable]. As

forced to use uniform rationing

among

the pool of applicants

and

not receive a job in the bureaucracy have no alternative but to enter the only

other occupation, the private sector. Misallocation arises because government's rationing does not

necessarily select the agents with a comparative advantage for the public sector. This will be an

important source of inefficiency in the model:

when

the

government

tries to

reduce corruption,

it

will

often deteriorate the allocation of the key resource of this economy; talent.

Diagrammatically, the sequence of decisions takes the following form;

successful

Ug Prob

Q

apply to bureaucracy

U^ Prob 1-Q

non successful

*

U^

apply to entrepreneurship

where Ug

Q

and

events

is

the ex ante expected payoff to a bureaucrat,

is

the expected payoff to an entrepreneur

the probability of getting a public sector job. After the choice of career, the timing of these

is

is

as follows.

12

match.E

Project assgn.P.M

*

*

In stage

U^

1

P

Match. B.

invests/returns

*

*

4

3

5

entrepreneurs match randomly. In stage 2 production and marketing functions are allocated

in each venture. In stage 3 the production entrepreneur, P, decides

this

Payoffs

*

investment decision, the return of the project

randomly with bureaucrats who can verify

can be bribed. Finally in stage

by bureaucrats.

It

realized. In stage 4, ventures are

the realized value of the project.

when bureaucracy

ventures will not have a bureaucrat; then, the

it

to invest or not

At

this stage

and since there

is

M

no way

8

is

less than full size (less

and

after

matched

bureaucrats

5, payoffs are paid to entrepreneurs according to the value

should be noted that

project and reports

is

whether

announced

than 1/3), some

entrepreneur observes the realized value of the

to falsify

it,

payments are based on

his report.

Obviously, in

be paid^

marketer will always claim

this case the

Vq-/?.

We

assignment stage

can

now

V=Vo and

the production entrepreneur will

write the expected return of an entrepreneur before the project

as;

2/

U^{a,T) =

"l

1-

^^^Tq(VrV,)

1-/

BJ

(2)

2/.

^±\V,-R^Max q(V,-V,)

ix^il-x)p)

-e;0

-a-T

1-/,

Let us

now

explain this expression.

When

an agent decides to become an entrepreneur, he does not

know what

function he will be assigned

to.

receive R.

However, he may

some

also get

entrepreneur invests (probability

hide

Yet, this can only happen

this.

Because

t), the

there

if

is

is

1/2, he will

additional returns;

if

become

the marketer and

the corresponding production

when

there

is

no bureaucrat assigned

he

will

be dishonest and appropriate

multiplied by l-llg/il-lg) which

gets Vq-R for sure but also

may choose

profitable to invest will

it

is

all

to invest

if

the bureaucrat

is

Thus

the returns.

this

the probability of not meeting a bureaucrat.

he

this case,

and obtain the net return of investment. Whether

depend on the probability of receiving the returns;

bureaucrat assigned to the project, he will never get the high return, as

and

try to

Why?

to this project.

Conversely, with probability 1/2, the agent becomes the production entrepreneur; in

he finds

may

return will be high (with probability q) and he

a bureaucrat, either he will be honest in which case the production entrepreneur

will get the additional returns or

second term

With probability

there

if

is

no

M will always claim V= V^,

dishonest, he will not receive the high return unless the bureaucrat

while taking bribes. Thus for the additional return to the production entrepreneur

we

is

caught

require the

venture to have matched with a bureaucrat (probability 21^(1-1^)), and the bureaucrat to be honest

(probability x) or to be dishonest but get caught (probability (l-x)p).

It

rights

follows from equation (2) that the decision to invest depends on the degree of property

enforcement as reflected by

First, the actual size Ig

X=

2[x+(1-x)pJIb/(1-Ib)- Three elements affect this probability.

of the bureaucracy. Second, the quality of the bureaucracy (the degree of

corruption) as captured by

j::

the

more corrupt

the bureaucracy, the lower are the

remrns to

investment and the weaker are the incentives to invest. Finally, the probability p of detecting

corruption;

if

corruption

is

detected, returns

from investment are reimbursed

to the

production

bureaucracy (expected

at the point

entrepreneur.

There are three possible cases for the expected return

*

to

Obviously since no one else other than the market entrepreneur observes the realized value of the project,

impossible to

make

the

payment

to the production entrepreneur

production entrepreneur equal to

R

is

depend on the actual return. Then setting the payment

without loss of any generality.

bureaucrat, the production entrepreneur receives R'

< Vg

A

it

is

to the

contract that specifies that in the absence of a

would give exactly the same

results.

of allocation of talent thus before honesty costs are known):

i) oio

< w

(Non corrupt bureaucracy)

Ugiw)

=

w

(3)

In this case, bureaucrats of both types only receive their wages which are high enough to discourage

w

bribes. Recall that

the net public sector wage, W-T. Also note that since a

is

of entering entrepreneurship, the return to bureaucracy

< w <

ii) o:,

is

independent of

is

defined as the cost

this.

(Partially corrupt bureaucracy)

<jJq

Ugiw)= il-Tqa)w + Tqaiw + V^-Vo){l-p)

= w ^TqapiijiQ-w)

where rq

T

is

is

,^.

the probability that a bureaucrat meets a venture with successful

the probability that the production entrepreneur invests].

mvestment

[recall that

With probability rqa a bureaucrat

dishonest and meets a venture with successful investment [only with no dishonesty cost

bureaucrat corrupt and this occurs with probability a]. In this case, the expected payoff

(w

is

+

Vj-Vq)(1-p).

With

because either he

iii)

w <

is

the

is

is

a

is

complementary probability l-rqa, a bureaucrat receives no bribes. This

honest and/or he meets a venture without a successful investment.

Uj (Totally corrupt bureaucracy)

Us(w)=(l-Tq)w^Tq[(w^V^-V^)il-p)-(l-a)y]

=

In this case

all

w

^^^

+ Tqp[a((jiQ-w)+{l-a)(io i-w)]

bureaucrats are corrupt. Hence with probability (l-rq), they do not meet a venture

with a successful investment and simply receive their wage w.

On

the other hand, with probability

Tq they match with a venture with successful investment and receive the bribe Vj-Vq. The expected

payoff

is

(w+

Vj-V()(l-p)

minus the expected cost of dishonesty; (l-a)y.

Given the net public sector wage

apply for a public office

talent a^

if

and only

such that agents above

the bureaucracy as

Ig

= Min

if

rate,

Ub(w)

this level

(1-a^, 1/3).

>

w, and the tax

meet an honest bureaucrat which

is

an individual with

talent

a

will

Ui:(a,T). This condition defines the cut-off level of

apply to the public sector. This also gives us the size of

For a given wage w, from

of honest bureaucrats, x(w), and derive the probability

to

T,

X=

[x(w)

(1)

we can compute

+ (l-x(w)p].

the fraction

2lg/(l-lg) for a

venture

a measure of property rights enforcement in our model.

Finally the investment decision in (2) gives us the probability that a bureaucrat will

with a successful investment, T(X)q. Thus, for a given value of

w

the equilibrium

allocation of talent represented as a^(w), a decision rule for bureaucrats

meet a venture

is

defined as an

which determines whether

they accept bribes or not, x(w) [and thus X'(w)], and an investment decision for entrepreneurs, 7^(w).

These can be summarized

in the

form of a vector

(a',

10

//, X', t^)

such

that:

fl^(H')=l-/(w;c(w),T^)

(6)

22^

X''iw)=[x(w)Hi-xiw)p].

^-Ib

in. Equilibrium Property Rights, Allocations and Investment

To

we

simplify the exposition

Assumption A: qf(l-a)

+

will first consider a configuration of parameters

apj. (V,-Vg)

<

e.

This condition ensures that ex ante investment

partially honest: with a full size

is

not profitable

thus need a

fiilly

profitable. In section

honest bureaucracy (though not necessarily of

V, we will return

investment by entrepreneurs

i)

< w

uq

(all

if

the bureaucracy

bureaucracy and a fraction of dishonest bureaucrats

a dishonesty cost of 0), the expected return of the investment, qf(l-a)

We

may

such that

to die case with e

<

+

apJ. (V,-Vq),

full size) for

q[(l-a)

+

is

only

a

(those with

is

less than e.

investment to be

apJ. (V/-Vy

where ex-ante

also be profitable under a partially honest bureaucracy.

bureaucrats are honest).

In this case, the return to entrepreneurship will depend on whether the production entrepreneurs find

it

profitable to invest; this will be the case iff

——q(Vy-VQ)>e

investment (t=7) as long as/g>/g=

q

——

^

-^

U,\a,T)A

that

when

there

is

Y -« -T

outcomes are equally

true \i x(w)

is:

if Ib>Ib

(7)

ifl,<i;

investment by production entrepreneurs, the size of the bureaucracy does not

matter for the expected return because

receives the rents, and

Expressed alternatively, there will

.T'hen the return to entrepreneurship

-^-a-T

Note

.

when

likely

were not equal

there

is

when

there

is

a bureaucrat, the production entrepreneur

no bureaucrat, the marketing entrepreneur does, and since both

ex ante, the size of the bureaucracy does not matter

to 1, see below]. Nevertheless, the size

features in determining whether investment

is

[this

would not be

of the bureaucracy crucially

worthwhile from the viewpoint of the production

entrepreneur.

The return

to bureaucrats in this

regime

is

simply given by (3) above; they are

11

all

honest and

'

Now we

only receive their wages.

can determine the equilibrium cut-off level for applying to a

public sector job, a'(w,T) such that

types

all

a>a^(w,T) apply

bureaucracy. First assume that

to

{t=1) and we get

Ib>Ib*-> then production entrepreneurs are expected to invest

that a'{w,T)='a'

(w,T) where

^^^»"^o)-g

a "(w,T) =

2

Clearly, for Ib>Ib'*''

it is

Alternatively,

,}^,T_^

(8)

2

necessary that l-a'*(w,T)>lB+.

if this

return to entrepreneurship

is

condition

is

not satisfied, then

t=0

lower, the cut-off level of talent

is

(no investment) and because the

given by a'(w,T)=a*(w,T) where

a '(w,T)=^-w-T

Both of these expressions depend on

T as

(9)

well as w. Imposing the government budget constraint,

we

can write

and where lB<^(w)=Min

l-a'(w,T)}. (10) can be explained as follows; there

{1/3,

bureaucrats receiving a net wage

of them. However,

when

paid their wages. There

w and

there are

is

this net

wage

is

is

a total of

/^

paid by the entrepreneurs and there are l-l^

some ventures with high

returns, not all of the bureaucrats are

a probability rq that a bureaucrat meets a venture with high return, and

a proportion 1-x of these bureaucrats will be corrupt and take bribes and a proportion/? of those will

get caught; hence

Now

a'(w)

we

subtract this proportion

substituting for

T from

=a* *(w) or a'(w) =a''(w),

form the

total

(10) into (8) and (9),

wage

we

bill.

obtain the cut-off level of talent,

as functions of the net public sector

wage

rate only.

The next lemma

establishes that both functions, a*(w) and c* *(w) are decreasing in the public sector

Lemma

1: a*{w)

and

a*

*(yv)

are continuously decreasing

in

Given the monotonicity of these functions, two other

wage

rate.

w.

critical

wage

levels

Wp and Wpp can be

defined such that

a'(Wp)=2/3 and a' '(Wpp)=2/3

and naturally Wpp>Wp. These wages are the

Ib=1/3 and therefore,

will

\iw>Wp and

there

be an excess number of applicants

randomly rationed. Figure

1

is

to

levels at

which the public sector reaches the

no investment

in the private sector, or if

full size,

w> vv^f,

there

bureaucracy and some of these jobs will have to be

shows the determination of w^ and

12

w^rf

diagrammatically.

< w <

ii) u);

A

(Partially corrupt bureaucracy)

uq

a of bureaucrats

fraction

are corrupt.

Due

to

assumption

A entrepreneurs

do not

the probabihty that a bureaucrat meets a venture with a successful investment

is

0.

invest, therefore

RecalUng

(2)

and

(4), this gives;

U,{a,T)=^-a-T

These expressions are the same as

than

(7)

Therefore, as found above,

Ig-^.

and

all

^^^^

(3) in the case

where the

individuals with talent

size of the

bureaucracy was

a larger than a*(w)

less

will apply to the

public sector.

w <

iii)

w; (Totally corrupt bureaucracy)

Entrepreneurs will not invest and bureaucrats have no bribe opportunities which makes

same

exactly the

as

(ii).

It

follows by inspection of Figure

equilibrium depends on the relative positions of

ojo,

whole characterization of the

that the

1

this case

w^, w^f.

< ug, then the equilibrium size Ib(w) is given by:

ifw< Vo/2-1

IbM =

= l-a*(w)

ifyc/2-1 < w < Wp

= 1/3

if Wp < w

Proposition 1: a) Ifw^ir

b) If

Wf

uq

<^

^

Wf/r,

then the equilibrium size /g(wj

=

=

=

=

=

IbM

c)Ifuo

^

^F- ^^^" 3

w" G

IbM

if Vo/2-1

1/3

l-a"(w)

1/3

=

=

=

—

Vo/2-1

< w < Wp

ifWp<w<(j}o

if<^o'^ ^ —'^FF

l-a*(w)

if^FF

[oio'^fJ' -^"^^ ^^^^ t^^

Figure 2 describes case

given by:

is

ifw<

— ^

equilibrium size lg(w)

ifw<

if Vo/2-1

l-a"(w)

ifw" < w < Wpp

1/3

if'^FF

Figure 3

illustrates

given by:

< w < w"

l-a'(w)

(a).

is

Vo/2-1

—

^•

case (b) while figure 4 shows case

(c).

In

all

diagrams the size and the quality of the bureaucracy are shown as a function of the public wage w.

When

the

wage

is

below Vy2

-1,

even individuals with a strong comparative advantage for public

jobs do not want to apply to these jobs, and the equilibrium size,

in the

wage

w makes

its

quality (or the level of corruption)

public jobs

sector. This in turn

more

attractive

and

.

On

on corruption

is

also present (e.g.

On

two channels: the

increase

the one hand, increasing the net

wage

of talent towards the public

less

than

full size

bureaucracy,

the other hand, the usual efficiency

Rose-Ackerman [1975]) and

13

An

of the

distorts the allocation

attractive.

equal to zero.

size

improves the enforcement of property rights for a

and consequently investment becomes more

effect

is

rate affects the equilibrium level of property rights through

bureaucracy and

rate

Ig,

wage

the quality of the bureaucracy

improves, which, holding the size of the bureaucracy constant, increases expected returns on

Which channel

investment.

matters

more

depends on the

for the protection of property rights

parameters of the model.

Case

(a) illustrates the situation

honest one. In

wage w. When Wpf

sector

honesty (Figure 2). In

honest and

full size

Case

in the

wage

fully honest

and

private

offices.

now

this case,

When

the

A

jobs,

No

Case

wage

reached before

when

attractive.

full

society has a fully

totally protected

bureaucracy

level exceeds the threshold level ug, the

who would

Consequently some agents

When

prefer to enter the private sector.

is

(w

>

oig).

not monotonic

bureaucracy becomes

o^q

<w <

w^^, this shift of talent to the

strong enough so that only less than a third of the people

is

cost:

(i)

now

apply to public

bureaucracy and no more rationing. This

less than full size

no

makes

otherwise apply for a public

free-lunch mentioned in the introduction: by increasing the

wage

rate at this point,

Less corruption and thus more investment,

number of agents who can work

in directly productive

rationing, hence a better allocation of talent.

(c)

and Figure 4

bureaucracy than to

all

size of the

is

non-monotonocity comes from a general equilibrium effect on the

smaller bureaucracy, therefore a larger

(iii)

bureaucracy (1/3)

where the equilibrium

three beneficial effects are being created at

(ii)

the honesty of the

a non-decreasing function of the public

investment by the private sector begins only

a consequence there

illustrates the

full size

is

profitable for entrepreneurs to invest in production skills. This in turn

more

is

is

bureaucracy and thus only when property rights are

it is

economy

As

bureaucracy

smaller than uq,

rate (Figure 3). This

the private sector

sector job

is

size of the

(b) describes a situation

allocation of talent.

easier to get a full size bureaucracy than a fully

it is

major constraint on protection of property rights

this case, the

The equilibrium

public sector.

where

attract

illustrate the situation

enough people

polar to

(a). It is

now

to enforce property rights.

bureaucrats are honest, the size of the public sector

is

For

easier to get a fully honest

ojq

< w <

w'

*,

although

too small to have property rights well

protected from the opportunistic behavior of marketing entrepreneurs and hence ex-ante investment

is

not profitable.

21b/(1-Ib) for a

to

When

w**

< w <

w^^,

we

still

have

venture to meet a bureaucrat (who

make investment

is

less than full

bureaucracy but the probability

in this case necessarily honest) is

high enough

profitable. After Wp^, the bureaucracy has full size, 1/3. Finally note also that

wage

in all cases, given the

enforcement of property rights

rate

is

and the equilibrium

in terms of the actions,

investment and

uniquely determined. This feature will enable us to conduct the

welfare analysis, and later the political equilibrium by looking at the public wage rate only.

rv. Optimal Property Rights and the Organization of the Society

In this section,

verifiability constraint

bureaucrats.

The key

we

on

characterize the optimal degree of property rights given the non-

the investment returns and the potentially opportunistic behavior of the

to this exercise will

be a trade-off between the allocation of

14

talent

and

wage

efficiency

Let us

w.

Two

considerations in the public sector to reduce corruption.

first

define l-a(w) as the

number of

individuals

who

apply to a public job with salary

cases have to be considered depending on whether there

rationing of pubic sector jobs, total surplus

is

is

rationing

or not.

With no

given by:

fl(w)

<2.(w) =

V'^

-«^^)--

^ ac

f

ada

2

2

where V*

2

the expected value of a pair of entrepreneurs (net of investment costs).

is

the bureaucracy given

a(w)/2 and

(12)

"

by l-a(w), only a(w)/2 ventures

total fixed costs

exist.

Therefore

total

With a

size

expected output

is

of

V

of entry into entrepreneurship are given by the integral of entry costs

over the agents in private sector. Hence equation (12) for net expected surplus.

With

rationing, total net expected surplus

a{w)

1

i

aU

3

_V'_l

3

Because there

is

is fiill

V/3. The two

last

(i.e.

given by:

3(1-«(M^))

(13)

^ l+ajw)

2^6

size bureaucracy, the

terms on the

RHS

number of ventures

of the

into the entrepreneurial sector given that there

public job

is

first line

that a utilitarian social planner

Proposition 2:

what follows we

is

will think of total surplus as a

<

ifw<Vo/2-l

ifVo/2-1

a'(w)(Vo-a'(w))/2

Vg/S - 1/3 + a'(w)/6

^(^1-^0)

-

1/3

-

Wp

<

oiQ

+

<

a"(w)/6

Wpp, then total surplus

is

given by:

Vo/2-1/2

ifw<

a'(w)(Vo-a'(w))/2

Vo/3 - 1/3 + a,(w)/6

if

[Vo

+

q(VrVo)

-

eJ/3

(Jig

Vo/2-1

< w < w^

<

<w< ug

if

i/a;^ < w < w^^

ifw^^ < w

Vo/2-1

w^

a"(w)(Vo +q(VrVo)-e-a'Uw))/2

c) If

QsM =

< w < w^

<

w

< uo

if

^

ifo^o^

Wp

eJ/3

b) If

measure of welfare

Wq, then expected social welfare is given by:

=

=

QsM =

=

=

=

=

to a

never incurred and does not feature

would maximize.

a) If w^f

+

of entry

uniform rationing for the people who apply

is

=y(/2-l/2

=fVo

total costs

those with talent a>a(w)). Also note that given assumption A, corruption and

in social surplus calculations. In

where

also 1/3 and total expected output

of equation (13) reflect

investment never coincide, hence the moral cost of honesty

QsM

is

-

<

1/3

+

a* *(w)/6

Wp, then total surplus is given by:

ifw<

y!/2-l/2

= a'(w)C/o-a'(w))/2

= a**(w)[Vo+q(V,-Vo)-e-a*^(w))]/2

= rVo + q(VrVo) - eJ/3 - 1/3 + a' '(w)/6

w" € foio-^rJ i^ defined in Proposition (Ic).

15

Vo/2-1

if Vo/2-1

< w < w"

ifw"<w<

ifw^^

< w

w^^

Figures 5, 6 and 7 plot the shape of social surplus function, Qs(w), in the three cases.

can see

curve

in all of these, the

non-monotonic

is

trade-off between allocation of talent and property rights protection.

wage

wage, w. This

in the public sector

On

As we

illustrates the

the one hand, increasing the

rate distorts the allocation of talent towards the public sector: first, the size

of the bureaucracy

increases; second, as public sector jobs offer rents, agents with a comparative advantage for the

private sector also apply to bureaucracy.

as well as a quality effect

On

—

on bureaucracy

attractive.

bureaucracy

small and/or corrupt and increasing the

For low wages, welfare

is initially

decreasing in the

wage has no

wage

rate

because the

effect other than distorting the

allocation of talent further toward unproductive bureaucrats. Yet a further increase in public

may improve

level, welfare

when

jumps up. In cases

the bureaucracy

is

welfare and investment

case (b), investment

full size after the

w*

*

with a less than

is

to

and

(a)

(b), the

jump occurs

honest and has already reached

attractive.

at w=(jJo. In (a),

full size.

At

wages

that threshold

investment

The binding

starts

constraint

for

therefore not the size, but the quality of the public sector. In the second

undertaken under honest and

is

jump

fully

(the free-lunch). Finally,

full size

flie

fiill

size

bureaucracy which becomes less than

increase in welfare in case (c) occurs at the

bureaucracy that has already reached

binding constraint for investment

due

and make private investment

the quality of the bureaucracy

size

and investment

the protection of property rights,

becomes more

is

wage improves ~ by a

the other hand, a high public

is

full

wage

honesty. In that situation, the

not the quality but the size of the bureaucracy. After the jump,

our dichotomous specification for investment, there

is

no further gain from having a higher

wage. Welfare declines again with wages since high wages only cause distortion in the allocation of

talent.

Note

that in regions

at a faster rate

is

less

who

where there

is

no

than otherwise. The intuition

rationing, the shape of the welfare function

is

quite simple.

The

distortion

on

is

declining

the allocation of talent

important with rationing of public jobs than without rationing, because some of the individuals

apply for a public job nevertheless

come back

Hence welfare only decreases now because,

comparative advantage for public jobs

the higher

is

the wage, the

who

as

to the private sector

more people

apply,

are admitted, but a

more agents want

to get a job in

it is

random

when

they are rationed.

not always those with the

selection of the applicants:

bureaucracy thus the more severe

is

the

misallocation of talent*.

Now

the

diagrammatically.

we

thus

socially

We

optimal

of property

rights

enforcement can be determined

can see that the social planner will only locate

at

one of the points

only need to compare the heights of these points in Figures 5, 6 and 7. At point

the welfare level associated with

'

level

Note

no bureaucracy and therefore no property

that in general the Social Planner can

independent of the public sector wage. If

this

rights

A

A we

or B,

have

and no investment.

have an additional instrament; to choose the size of the bureaucracy

were allowed,

in (a)

and

(b) above, the Social

Planner would choose a lower

size of bureaucracy. Yet, the costs of enforcing property rights in terms of misallocation of talent

our general results would continue to apply.

16

would

still

remain and

all

Point

corresponds to the welfare level with a fully honest bureaucracy and private investment.

B

However, note

point

and

that in cases (b)

B because

the bureaucracy

there

(c),

is less

than

is

optimal for societies to try to enforce

all

property rights are optimal

full

are necessary for investment.

From

When Wfp <

it

will not in general be

the property rights. In our model, the only situation in

when

is

of property rights at

and some ventures will not be matched with

full size

an economically costly activity

bureaucrats. Thus, since enforcement

which

less than full protection

is still

a;(,>Wyr/r

Proposition 2,

we

which

is

the case

where

property rights

full

also get:

wage is Ug and there is full size honest

[Vg

+ (1(^1-^0) ^V^ 1/3 + a' '{i^^/6.

if:

wage

equal

to

and there is no bureaucracy.

public

is

optimal

the

Otherwise

<

optimal

public

wage is ug and there is less than full size honest

the

socially

<

wq

w^

b) When

Wp-f,

<

-1/2

Vgll

a'

and

only

bureaucracy if

if:

YwoJ/Vo+ q(VrVg} -e - a' '(<^o)]/2

wage

is

equal

to

and no property rights are enforced.

optimal

public

Otherwise the

Proposition 3: a)

bureaucracy if and only

When ug <

cjg,

Vg/l -1

the socially optimal public

<

wage is w' * as defined in Proposition Ic and there is

and

only

honest

bureaucracy

less than full size

if

if: Vg/2-1/2 < a**(w'*)[Vg+q(V,-Vo)-e-a**(w**)]/2.

public

wage

is

equal

to

and there is no property right enforcement.

Otherwise the optimal

c)

w^, the socially optimal public

This proposition constitutes the

first

part of our key result.

The optimal organization of

society will involve rents to public sector employees and misallocation of talent.

observations are not proof of government failure. The reason

is

intuitive;

And

the

yet, these

property rights are

necessary for the redistribution of ex post rents according to ex ante agreements. This however

implies that there will be ex post incentives to violate these property rights, and the rents for the

goverimient employees arise in order to prevent such violations (corruption). As soon economic rents

exist in

one sector, some misallocation of resources

talent, thus the allocation

of talent gets distorted.

is

An

unavoidable, and here the key resource

important point to note, however,

optimal organization of society here does not involve actual corruption, for which

assumption

It

Murphy,

is

A

is

that the

we need

to relax

in the next section.

often stated that economies with high levels of corruption (e.g. Klitgaard [1988],

Shleifer and Vishny [1991]) or those with

Rosenberg and Bridzell [1986]) grow

sectors.

is

Such a correlation appears

Underlying these statements

is

less

weak property

(e.g.

Mauro

it is

informative to investigate

the equilibrium property rights.

[1993], Svensson [1994]).

a view in which the level of corruption and the degree to which

property rights are enforced are exogenous. Since our paper suggests a

of property rights,

North [1981],

because they do not mvest enough in their corporate

be in the data

to

rights (e.g.

To do

this

we

how

way of endogenizing

the level

corporate investment opportunities influence

interpret the profitability of investment V,-Vg as a

measure of corporate investment opportunities. However, inspection of Proposition 3

will reveal that

increasing Vy-Vg creates two opposing effects; the social benefit to higher enforcement increases, but

since the efficiency

wage

that bureaucrats

need to be paid

is

also increasing in this variable, the cost

of higher property rights in terms of misallocation of talent also

17

rise.

However,

as should be

expected, the

dominates the second, and as a

direct, effect

first,

result,

economies with higher

corporate investment opportunities should indeed choose a higher degree of property

rights

protection.

This statement can be illustrated in Figure 8 which

necessary efficiency wage,

relevant region

rights at

some

is

a

full

is

DD

divided into three areas. Below curve

level of property rights enforcement.

move

along the line

VV

in the space of (uq.tt), i.e. the

and expected returns from investment, which we denote by

ojq,

Above DD, because investment

all.

drawn

is

in this

is

An

tt.

The

not profitable to protect property

it is

sufficiently profitable,

it

is

socially optimal to

have

increase in corporate investment opportunities, V,-Vq,

diagram and

this takes

Thus

or partial property rights enforcement.

us from the no property rights region to

differences

overall,

in

the

productivity of

investments across countries or time that are driven by autonomous factors will influence both the

optimal and the equilibrium level of property rights. Therefore, in interpreting cross-country

evidence,

it

has to be borne in mind that both the degree of corruption and the investment levels are

endogenous.

It is

rights

also worthwhile to

and corporate

modernization

is

activities

remark

may

that this general equilibrium relationship

also help us explain Huntington [1968]'s observation that political

often associated with an increase in corruption. This

that in autocratic

may be

due

partly

to the fact

corporate opportunities are low, therefore, although public sector

societies,

employees may be willing

between property

to accept bribes, there are

no bribes

to

be received. Modernization may

thus enable corporate investment opportunities to be exploited which could in turn increase the

observed incidence of corruption (see next section).

v. Partially Corrupt Bureaucracy and Investment

So

far

we have assumed

honest (assumption A).

By

implication, for a given

in equilibrium. In this section

the bureaucracy

is

wage

Since

rate w, actual bribes will

never be observed

consider the case where

<

e

<

q.f(l-a)

+

it

could be profitable to invest although

we have now

with no corruption,

relaxed assumption A,

full size;

Wffr.

one with

full

will

we

with;

III.

Again

cjq

and u, are defined as the

be indifferent between honesty and corruption.

will

need to define three wage levels for the

corruption, w^; one with partial corruption, Wp, and one

The wages Wf and w^p

to write the return of

A

apj. (Vj-Vg).

which the two types of bureaucrats

bureaucracy to reach

(if

bureaucrats were

analysis in this case will follow that of section

levels at

Wp we need

we

wage

if all

be profitable only

not totally honest, by replacing assumption

Assumption B: q.p. (V,-Vo}

Our

that investment could

are exactly as

an entrepreneur when there

defmed

is

in Section III.

partial corruption

To determine

and investment

investment were not profitable then a' would apply and the relevant cut-off level would be Wp).

This return to entrepreneurship

is

equal to

18

qiVrVo)[l-^a(l-p)]-e ^

^

U^(a,T)=

and the return

the

to entering

government budget

bureaucracy

we

constraint,

is

^Y~"~'^

given by (4) above.

By

substituting for the tax rate

from

again obtain the cut-off level of talent, this time denoted by

aP(w) = ^^l[qiV,-V,)-e] -J-apqic^.-w)

Next similar

our previous analysis,

to

bureaucracy becomes

depend on the

easy to show

Lemma 2:

now Wp is

2/S where

we

the

wage

at

which

now

with partial corruption. The characterization of equilibrium will

relative positions of the

wage

rates v/f, -Wpf, >Vp

and wq and wy. More precisely,

it is

that:

Lemma would

we want

purpose

=

-IfwQ< w^^, then w^ < Wpf < Wp.

- IfWpp < Wo < Wf+[q(Vj-Vo)-eJ/(3apq)

then Wf < Wp <

- If Wp+fq(V,-VQ)-eJ/(3apq) < Wg then Wp < Wp < Wpp.

This

here

full size

us define a^{w^)

let

be useful in

reached, but until

oj; all

this case,

were missing from the analysis of Section

<

only consider the case where Wp

wage

of

fully characterizing the equilibrium

to highlight the features that

as a fiinction of the public sector

w^p.

rate

is

u,

< Wp <

shown

Wpp

<

in Figure 9.

bureaucrats are corrupt and there

oig.

The

At Wp,

III.

For

this

size of the bureaucracy

full size

no investment. After

is

however,

bureaucracy

this

wage

is

rate,

bureaucrats with positive dishonesty costs no longer accept bribes, therefore entrepreneurs are

therefore willing to invest. But once this

and the number of applicants

attractive,

bureaucracy

size

the

is

still

given by

wage

we

to

the

L

=

.

Thus

to

the

From

that point on,

it is

is

number of

up and

The welfare

analysis

is

o:,

applicants cannot fall

at

Wp,

it

reaches

below

full size,

The new

aig,

feature

the

but

/„*

*.

we

As

still

at full size

no corruption regime,

compared

to the previous

and ug investment and bribes coexist.

also similar to before. In particular, since agents with a positive cost

of dishonesty never receive bribes, (12) and (13)

can establish the following

Nevertheless,

immediate that bureaucracy remains

characterized by full size bureaucracy.

the fact that between

relatively

induce entrepreneurs to invest, and this critical

reach the no corruption regime. Further, as Wppis smaller than

is

becomes

public sector suddenly drops.

rate mcreases, the size of bureaucracy goes

starting at wq,

sections

rate is exceeded, the private sector

needs to be of a sufficient size

only have partial honesty.

until

wage

still

apply exactly.

By

inspecting (12) and (13),

we

result;

Proposition 4: Let w* be the wage rate where investment becomes profitable with partially corrupt

bureaucracy and w* * the wage rate where investment becomes profitable with fiilly honest

bureaucracy. As long as a**(w' ') < a'' (w*), the Social Optimum never has fiilly honest bureaucracy.

19

This proposition completes our key

can include rents and misallocation of

introduction, this

is

more

a

precisely the opposite reason; the Social Planner

is

the society not only

but also actual corruption. Yet, as emphasized in the

talent,

not because corruption

is

The optimal organization of

result.

is

because of

efficient allocation system, but

trying to implement an efficient allocation that

not easy to implement ex post. In particular, the transfers that are required to take place (from the

M to P entrepreneurs) create room for corruption.

incentives, but preventing all corruption

is

Too much corruption would

destroy investment

also too costly.

VI. Political Equilibrium

In

many

influenced by the wishes of the majority and

economy