Document 11163162

advertisement

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/persistenceofpowOOacem

DEWEY

HB31

.M415

c?3

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

PERSISTENCE OF POWER, ELITES

AND

INSTITUTIONS

Daron Acemoglu

James A. Robinson

Working Paper 06-05

February 28, 2006

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 021 42

This paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http://ssrn.com/abstract=8881 87

Persistence of Power, Elites and Institutions^

James A. Robinson^

Daxon Acemoglu^

This Version: February 2006.

Abstract

We

construct a model of simultaneous change and persistence in institutions.

The model

and workers, and the key economic decision concerns the form

(e.g., competitive markets versus

labor repression). The main idea is that equilibrium economic institutions are a result of the

exercise of de jure and de facto political power. A change in political institutions, for example

a move from nondemocracy to democracy, alters the distribution of de jure political power,

but the elite can intensify their investments in de facto political power, such as lobbying or

consists of landowning elites

of economic institutions regulating the transaction of labor

the use of paramilitary forces, to partially or fully offset their loss of de jure power.

In the

baseline model, equilibrium changes in political institutions have no effect on the (stochastic)

equilibrium distribution of economic institutions, leading to a particular form of persistence in

we refer to as invariance. When the model is enriched to allow

on the exercise of de facto power by the elite in democracy or for costs of changing

economic institutions, the equilibrium takes the form of a Markov regime-switching process

equilibrium institutions, which

for limits

with state dependence. Finally, when we allow

tutions

is

more

for the possibility that

insti-

than altering economic institutions, the model leads to a pattern of

difficult

captured democracy, whereby a democratic regime

tions favoring the elite.

changing political

The main

may

ideas featuring in the

survive, but choose

model are

economic

institu-

illustrated using historical

examples from the U.S. South, Latin America and Liberia.

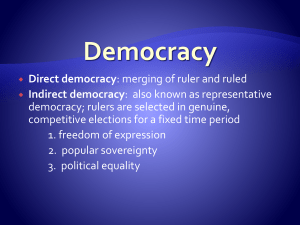

Keywords: democracy, de facto power, de jure power, dictatorship,

elites, institutions,

labor repression, persistence, political economy.

JEL

Classification: H2, NIO, N40, P16.

*We thank Alexandre Debs for excellent research assistance and Lee Alston, Timothy Besley, Alexandre

Debs, Stanley Engerman, Michael Munger, Nathan Nunn, Torsten Persson, Konstantin Sonin, Gavin Wright and

Pierre Yared and seminar participants at Clemson, ITAM, Princeton, Rochester, and the American Economic

Association Annual Meetings for comments.

Acemoglu

gratefully acknowledges financial support

from the

National Science Foundation.

^Massachussetts Institute of Technology, Department of Economics, E52-380, 50 Memorial Drive, Cambriudge MA02142. e-mail: daron@mit.edu.

'Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge St., N309, Cambridge MA02138;

e-mail: jrobinson@gov.harvard.edu.

meme

"Plus ga change plus c'est la

"The domination

The power

who

of an organized minority

any minority

of

chose." French Proverb.

is

over the unorganized majority

...

irresistible as against

is

organized for the very reason that

it

is

inevitable.

each single individual in the majority,

stands alone before the totality of the organized minority.

minoritj'

is

At the same time, the

a minority." Gaetano Mosca (1939,

p.

53).

Introduction

1

Current empirical work and theoretical discussions of the impact of institutions on economic

development either implicitly or exphcitly assume that institutions persist

Engerman and

Sokoloff, 1997,

North, 1990,

(e.g.,

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2001, 2002). In

fact,

some

of

the most popular empirical strategies in gauging the efTect of institutions on economic perfor-

mance use the

and

persistence of institutions over centuries as part of their conceptual approach

identification strategy.

periods

much

America and

But many aspects

shorter than a century.

Africa, have

Many

changed their

of "institutions"

show substantial change over

less-developed countries, especially those in Latin

political institutions all too often over the past 100

between democracy and dictatorship

years, with frequent switches

(see, e.g.,

Acemoglu and

Robinson, 2006a) and multiple changes in constitutions.^

The same

pattern also emerges

many historians and economists

practices such as the

plantation complex,

when we turn

economic institutions. For example, while

trace the economic problems of Latin

America to

colonial labor

encomienda or the mita, and those of the Caribbean to slavery and to the

all

of these economic institutions vanished long ago.^

of change, however, economic systems often

tural labor relations in

after colonialism,

to

many

and perhaps

of the Latin

show surprising

continuity.

Beneath

this pattern

The form

of agricul-

American and Caribbean countries changed

relatedly, these societies continued to suffer various

little

economic

problems, slow growth, and economic and political instability throughout the 20th century.

Another interesting example comes from the U.S. South. Even though slavery was abolished

at the

end of the Civil War, the U.S. South maintained a remarkably similar agricultural

sys-

tem, based on large plantations and low-wage uneducated labor, and remained relatively poor

'For instance, Colombia had 8 constitutions in the 19th century (Gibson, 1948), while Bolivia had 11 (Trigo,

1958) and Peru 9 (Palacios and Guillergua, 2003).

^In Latin America, the last form of official forced labor, pongueaje, was abolished in Bolivia in 1952 (Klein,

1992, Chapter 8).

freed, for

example

Unpaid labor services lasted

in

lasted until in 1886 in

in Guatemala until 1945 (McCreery, 1994). Slaves were gradually

Colombia. In the British Caribbean slavery was abolished after 1834, though it

Cuba and 1888 in Brazil.

1850

in

until the

middle of the 20th century.

In this paper,

we provide a

possible explanation for this paradoxical pattern of the coexis-

tence of frequent changes in political institutions with the persistence in certain (important)

Our approach

aspects of economic institutions.^

The

of persistence.

baseline

model leads

illustrates the possibility of

to a pattern

which we

two

different types

refer to as invariance,

whereby

a change in political institutions from nondemocracy to democracy leads to no change in the

(stochastic) equilibrium process of

in society.

we

economic institutions and of the distribution of resources

Simple extensions of our baseline model lead to a richer form of persistence, which

refer to as state dependence; the probability that a society will

tomorrow

pro-citizen economic institutions)

The underlying

idea of our approach

is

is

be democratic (and have

a function of whether

it is

democratic today.^

that equilibrium economic institutions emerge from

the interaction between political institutions, which allocate de jure political power, and the

distribution of de facto political

power across

social groups (see

Acemoglu and Robinson, 2006a,

and Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2005b). De Facto power

by institutions (such

weapons or

as elections), but rather

is

is

power that

is

not allocated

possessed by groups as a result of their wealth,

ability to solve the collective action problem.

A

change

in political institutions

that modifies the distribution of de jure power need not lead to a change in the equilibrium

process for economic institutions

of de facto political

paramilitaries)

.

power

The

if it is

(e.g., in

central

associated with an offsetting change in the distribution

the form of bribery, capture of the political parties, or use of

argument

in this

paper

is

that there

is

a natural reason to expect

changes in the distribution of de facto political power to partially or entirely

in

offset

changes

de jure power brought about by reforms in specific political institutions as long as these

reforms do not radically alter the political structure of society, the identity of the

source of economic rents for the

To make these

and the

citizens.

ideas precise,

elites, or

the

elites.

we develop a model

The key economic

consisting of two groups, a landed ehte

institution concerns the organization of the labor mar-

^Throughout, persistence refers to the continuity of a cluster of institutions, for example, the extent of

enforcement of property rights for a broad cross-section of society. Lack of property rights enforcement may have

its roots in quite different specific economic institutions, for example, risk of expropriation by the government

or elites; extreme corruption; economic systems such as serfdom or slavery preventing large segments of the

population from selling their labor freely or from investing in most economic activities; legal rules making it

impossible for those without political connections to have their contracts enforced; or entry barriers creating a

non-level playing

field.

''We refer to this type of persistence as "state dependence" since the probability distribution over equilibrium

political

and economic institutions tomorrow depends on the "state" of the system, which

is

political institutions

today. See Page (2006) for a discussion of richer forms of persistence in political systems, where the past entire

sequence of events, rather than simply a low-dimensional state vector, might influence future outcomes.

whether wages are competitive or are repressed below

ket, in particular,

model, economic institutions are decided either by the landed

depending on who has more

In the

the citizens (workers)

elite or

Political power, in turn,

political power.

this level. ^

determined by both

is

pohtical institutions that allocate de jure power and the distribution of de facto power, which

is

derived, at least partly, from a social group's ability to solve their collective action problem.

A

key observation

that landowners, by virtue of their smaller numbers and their established

is

position, have a comparative advantage in solving the collective action

amount

Olson, 1965). This implies that the

of de facto political

librium outcome, and responds to incentives.

political

power

power

litical

is

matter

also

for

effectively,

may

democracy de jure potowards the citizens

tilted

and the

help the citizens in solving their collective action problem

thus facilitating their exercise of de facto political power.

Those with greater

field is in this contest.

is

a "contest" between the

elite

(democracy versus nondemocracy) determine how

political institutions

today and

is

in

an equi-

and de jure

addition, freedom of political organization

In the model society, in every period there

and

elite is

Nevertheless, political institutions

allocated to the majority, so the balance of power

existence of political parties

more

power of the

equihbrium outcomes. For example,

Acemoglu and Robinson, 2006a). In

(see

problem (Mosca, 1939,

The most

tomorrow.

political institutions

that, because the elite's de facto political

political

power

is

and the

level

citizens,

the playing

power determine economic institutions

framework

interesting result of our

an equilibrium outcome,

is

will partly or

it

entirely offset the effect of changes in political institutions. In particular, the elite will invest

more

de facto political power in democracy than in nondemocracy.

in their

In the baseline model, this effect

economic institutions

is

identical in

of invariance defined above. ^

is

sufficiently strong that the distribution of equilibrium

democracy and nondemocracy

This pattern shows that

it

—thus leading

could be mistaken to infer from

frequent changes in certain dimensions of political institutions that there

persistence.

The

result also starkly illustrates

political institutions

to the pattern

how changes

in

some

is little

can be undone by the greater exercise of de facto

specific

institutional

dimensions of

political

power by the

elite.

Even though

institutions

is

in this baseline

model the equilibrium probability distribution of economic

independent of whether the society

ability distribution

is still

''Although this setup

is

affected

is

democratic or nondemocratic, this prob-

by economic fundamentals. The comparative

natural from the view point of Latin American history,

it

is

static results

not essential to the

results.

^To be

institutions

precise, there are

is

changes

in

economic

invariant to political institutions.

institutions,

but the equilibrium distribution of economic

illustrate this.

for

The most

interesting

among

these

that the economic structure of the society,

example the presence of sectors competing with agriculture

effect

on the equilibrium. The more productive are these

from using repressive methods, and the more

Second, the smaller the numbers of the

will

is

elite,

likely

it

for labor, will

sectors, the less the elite

is

political

the more cohesive they are and the more able they

advantage created by a democracy

lead to a greater domination of politics

by the

advantage of the citizens creates a future cost

elite.

for the elite

and they are

become an absorbing

The

Finally,

for the citizens

cost.'^

willing to invest

may

more

in

However, when democratic

institutions create a sufficiently large political advantage for the citizens

"sufficiently strong"), the nature of the

favor.

This result follows because the democratic

de facto power to avoid this future

activities to increase their

have to gain

that institutions favor the citizens.

be to solve the collective action problem and choose the institutions they

and more paradoxically, the

have a major

(i.e.,

when they

are

equihbrium changes qualitatively, and democracy may

state.

invariance result, that the de facto political power of the elite can entirely offset

the effect of changes in political institutions,

is

special.

In the rest of the paper,

we extend

our baseline model in a number of ways to show how, more generally, the de facto political

power of the

elite

only partially undoes the effect of changes in political institutions, leading

to an equilibrium with a

Markov regime-switching

The two extensions we consider

structure.

allow democracy to place limits on the exercise of de facto power by the elite

their use of paramilitaries or co-option of politicians)

economic institutions

may be

difficult in

(e.g., limits

on

and introduce the feature that changing

the short run

(e.g.,

because the democratic regime

has already implemented some changes favoring the citizens). Both of these extensions lead

to an equilibrium structure where the society switches between

democracy and nondemocracy.

with different sets of economic institutions in the two regimes, and exhibits state dependence

(so that

nondemocracy

Finally,

is

we analyze a

more

likely to follow

richer

the sense that, in democracy,

it

model

is

more

in

nondemocracy than

which

it is

to follow democracy).

political institutions are

difficult for

may

durable, in

the elite to change political institutions

than economic institutions. This model leads to a phenomenon which we

democracy] the equilibrium

more

refer to as captured

feature the emergence and persistence of democracy for a

long span of time, but throughout the economic institutions will be those favoring the

elite.

In

^It is also interesting that in this baseline model, there is greater inefficiency in democracy than in nondemocracy, because in democracy the economic allocations are the same as in nondemocracy, but there is

greater exercise of de facto political power by the elite, which is costly. This result suggests some insights about

why certain potential reforms in specific political institutions in many less-developed countries may have failed

to generate significant economic growth and also perhaps about why the post-war economic performance of

democracies

may have been no

better than those of dictatorships

(e.g.,

Barro, 1997).

fact,

paradoxically, this extended

somewhat

of labor-repressive institutions

is

model predicts that the equilibrium probability

higher in democracy than in nondemocracy, motivating the

term captured democracy.

The model

broken.

It

also sheds

some

light

on how institutional persistence can be diminished or

suggests that an effective democracy requires both reforms in specific political

institutions (such as voting rules or electoral procedures), but also a

facto political

power of the

which can be achieved

elite,

ability to capture the political system, or indirectly

directly, for

way

of curbing the de

example, by reducing their

by reforming the economic structure so

that with reduced land rents, they have less incentive to thwart democracy.

The model's

insights enable us to interpret the experience of

in a different light. For

diuring the colonial era,

less

developed countries

example, in the Americas, labor repression was of central importance

and was achieved by various means including the encomienda, the

Yet repression did not end when the mita and slavery were abolished.

mita, and slavery.

It

many

continued with domination of politics by local landed

elites,

with the creation of labor

market monopsonies (Solberg, 1969, McGreevey, 1971, Coatsworth, 1974, McCreery, 1986),

and the systematic threat

of violence against peasants in rural areas.

Similarly, in the sugar

plantations of the British Caribbean, Natal or Mauritius, slavery was replaced by the use of

cheap indentured laborers from the Indian subcontinent (Tinker, 1974, Northrup, 1995). In the

impede

U.S. South, slavery was replaced by monopsonistic arrangements, policies designed to

labor mobility, political disenfranchisement, intimidation, violence and lynching.^

Our paper

(e.g.,

is

related to the literature on the persistence of institutions in political science

Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth, 1992, Pierson, 2004, Thelen, 2004), though

this literature focuses

it

follows works

on

on how

'hysteresis'

much

specific institutions persist over long periods of time.

by David (1985) and Arthur (1989) on the lock-in of

of

In this

specific

technologies based on increasing returns. In addition to these approaches, persistence of institutions can arise in models in which social conventions or

and learning

(e.g..

norms emerge from

Young, 1998, Bednar and Page, 2006), and

specific investments in activities

in

models

in

local interactions

which agents make

whose value would be destroyed by changes

in social arrange-

in the paper beg the question of how the elite are able to exercise

democracy. This is also discussed in detail in Section 7, where we present a number

of historical case studies illustrating the pattern of persistence modeled here and also emphasize two specific

channels: the capture of the party system by the elites and the threat of violence. Both these methods were

This discussion and the general approach

de facto political power

in

extensively used in the U.S. South after the Civil War and are still present in many Latin American countries

such as Brazil, Bolivia or Colombia. For the U.S. South after the Civil War, see Key (1949), Woodward (1955),

Wright (1986), Alston and Ferric (1999), and Ransom and Sutch (2001), for Colombia, see Dix (1967), Wilde

(1978), Hartlyn (1988)

and Kline (1999), and

for Brazil, see Chilcote (1990)

and Hagopian (1996).

ments

(Dixit, 1989a,b,

Coate and Morris, 1999). Institutions could also

existence of multiple steady-state equilibria

(e.g.,

Krugman,

1991,

persist because of the

Matsuyama,

The

1991).

popular idea that economic inequality or certain forms of natural resource endowments

the balance towards bad institutions

and state dependence), since

is

also different

None

2005).

from our notion of persistence (invariance

this idea stresses the persistence of

then lead to the persistence of institutions

(e.g.,

tilt

Engerman and

of these approaches have addressed the issues

we

economic characteristics that

Sokoloff, 1997,

Benabou, 2000,

discuss here, in particular, the

coexistence of persistence and change.

From a modeling

point of view, this paper extends the framework in Acemoglu and Robin-

son (2000, 2001, 2006a), where de facto political power drives changes in political institutions

and the future distribution of de jure

model the process of the

elite investing in their

significant differences in the results.

more

"pro-citizen"

,

political power. ^

The major

difference

is

that

we now

de facto political power, which leads to some

While our previous work emphasized that democracy

the analysis here shows this

may

not be the case

if

the elite are able to

garner sufficient de facto political power in democracy. ^'^ In this respect, the current paper

and Sala-i-Martin (2004) and Mulligan and Tsui

related to Mulligan, Gil

on similarity

of various policies

(2005),

of our terminology, they explain this similarity by lack of significant de jure

in

is

which focus

between democracies and nondemocracies, though,

between regimes, while our model emphasizes how changes

is

in

terms

power differences

de facto power can undo real

changes in de jure power.

The

rest of the

political

paper

environment.

is

organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the basic economic and

Section 3 characterizes the equilibria of the baseline model, and

tablishes the invariance result

framework

in

and the main comparative

a number of directions and shows

partial offset will occur,

and the equilibrium

will

Section 4 generalizes this

statics.

how under more

general circumstances, only

correspond to a Markov regime- switching

model, with fluctuations between democracy and nondemocracy.

model

in

stitutions

which changing

political institutions

is

more

difficult

Section 5 introduces the

than influencing economic

and shows how an equilibrium pattern of captured democracy can

elites dictating their favorite

how simultaneous reforms

economic institutions

in multiple

es-

in

arise

in-

with landed

democracy. Section 6 briefly discusses

dimensions of political institutions or economic institu-

^See also Ticchi and Vindigni (2005), Jack and Lagunoff (2006), and Lagunoff (2006) for related approaches.

among others, Austen-Smith (1987), Baron (1994) and Grossman and Helpman (1996) on models

models where the equilibrium policy in a democracy is affected by lobbying. Our approach is more reducedform, but explicitly models the incentives of individual agents to contribute to lobbying- type activities, is

dynamic and endogenizes not just policies but also institutions.

'"See,

tions can be effective in breaking the cycle of persistence in economic institutions. Section 7

discusses a

number

of historical case studies that

both motivate and substantiate the ideas

in

the paper. Section 8 concludes.

Model

Baseline

2

Demographics, Preferences and Production Structure

2.1

Consider an infinite-horizon society in discrete time with a unique

by a continuum

1

of worker/citizens

and

(a finite)

M>

number

the same risk-neutral preferences with discount factor

/3,

1

good and populated

final

of the elites. All agents have

given by

oo

at time

We

t

where

cj_^

•

use the notation

All workers

elite

i

where

denotes consumption of agent

i E.

own one

£

to denote an elite agent,

unit of labor,

i

at time

and

which they supply

to

L

produce the unique

is

a

in the

a normalization)

economy, with no alternative use, and each

.

There

elite

is

owns

F

maximum

which each producer runs into severe diminishing returns (where the

is

citizen.

Each member

denotes land and N^^ denotes labor used by this producer, and

returns start after land size of L/Ad

to

j in terms of the final good.

inelastically.

returns to scale. This production function implies that there

after

-|-

£ C to denote a

i

E £ has access to the following production function

U

f

final

of the

good:

exhibits constant

land size of

L/M

fact that diminishing

a total supply of land equal

L/M

units of land (and no

labor)."

The

final

good can

also

be produced with an alternative technology, which can be

in-

terpreted as small-scale production by the laborers themselves (or a low productivity proto-

industry technology). This alternative technology exhibits constant retinrns to scale to labor:

Ya "The

market to save space.

is

introduced to prevent an allocation in which

free-rider

same reason, if initially

become concentrated in

(3)

all land is owned by one individual,

problem in investment in de facto political power, explained below. For the

there were M' >

land owners, given the production function in (2), land would

the hands of

land owners. We do not explicitly discuss transactions in the land

diminishing returns

which would solve the

ANA.

M

M

good

Clearly, total output of the unique final

the market clearing condition for labor

economy

in the

will

be

y=

Ylies '^l'^^a, and

is

Y.NI + Na<1.

The main

this

role of the alternative technology, (3), will

(4)

be to

restrict

In the

first,

how low wages can

fall

in

economy.

We

consider two different economic institutions.

Given

tive}'^

since

F

When

(2),

each

elite will hire

N1 — Nl/M

exhibits constant returns to scale,

we denote by r

is

== 1,

Nl =

The return

c denotes "competitive".

1

—

iV^,

and

as:

the wage rate (and the

of each worker), as a function of labor allocated to this sector,

where the superscript

markets

units of labor, where

we can write per capita output

there are competitive labor markets, which

wage earnings

labor markets are competi-

Ni,

is

therefore:

to landowners with competitive

similarly

R^m^f\-^^,

with each landowner receiving

Assumption

(7)

R^L/M.

1

/(L)-L/'(L)>A

This assumption implies that even when

wage

in this sector

is

Nl =

1

(i.e.,

when L/Nl =

L), the competitive

greater than the marginal product of labor in the alternative technology.

Therefore, both the efficient allocation and the competitive equilibrium allocation will have

workers allocated to the land sector,

wage and

i.e.,

N^ =

all

In light of this, the relevant competitive

1.

rental return on land will be

w''

=

w'^INl

=

I]

=

f (L)

-

Lf {L)

(8)

and

R''

'This implies that, by law, landowning

= R'[Nl =

elites

cannot

l]

=

f' {L)

restrict their labor

(9)

demand

to affect prices.

Consequently, factor prices at time

w

{Tt

=

The

1)

^w"

and Rt

= R {n =

t

1)

as a function of

=

/^^ with

economic institutions are given by Wt

w" and

R'' as

defined in (8) and {9)}^

alternative set of economic institutions are labor repressive {rt

landowning

elite to

slavery

(i.e.,

is

institutions are labored oppressive, the lowest

Nl >

0)

and allow the

0, is

They

not allowed), so workers always have

wage that the

when economic

Consequently,

access to the alternative small-scale production technology.

ensuring that

=

use their political power to reduce wages below competitive levels.

cannot, however, force workers to work

—

elite

can pay the workers, while

still

A. This imphes that factor prices under these economic institutions

are

=

w''

A,

(10)

and

R'^f'-j-^.

(11)

Ju

(Recall that the landed elite are paying the

wage of

economic institutions are labor repressive, then we

R {rt —

0)

— R^ Assumption

.

1

A

will

to a total of

have wt

immediately imphes that R^

economic institutions wages are kept

greater rents. For future reference,

artificially low, i.e., w'^

we

Nl =

— w [rt —

When

— w^ and Rt =

workers).

1

0)

>

R'^,

since with labor repressive

<

w'^,

so that land owners enjoy

define

AR = R'-R"

f{L)-A f (L) >

L

One

feature to note

tive labor

is

0.

(12)

that the simple environment outlined here implies that both competi-

markets and labor repression

will

generate the same total output, and will differ only

in terms of their distributional implications.

Naturally,

costs from labor repressive economic institutions,

distortions or other costs involved in monitoring

it

is

possible to introduce additional

which may include standard monopsony

and forcing laborers

to

work

at

below market-

clearing wages (such as wasteful expenditures on monitoring, paramilitaries, or lower efficiency

of workers because of the lower

"More

payments they

formally, the second welfare

equilibrium

is

receive). Incorporating such costs has

theorem combined with preferences

in (1) implies that

no

effect

a competitive

a solution to the following program:

max

/(^^Nl + ANa

subject to (4) and L < L. Assumption 1 ensures that the solution involves

equilibrium factor prices are given by the shadow prices of this program.

Nl =

1

and L

=

L,

and the

on the

analysis,

and throughout, one may wish to consider the labor repressive

institutions as

corresponding to "worse economic institutions"

Political

2.2

Regimes and De Facto

There are two possible

political regimes,

denoted by

and nondemocracy. The distribution of de jure

regimes.

At any point

which designates the

Power

Politiccd

D

and

corresponding to democracy

A^,

power

political

in time, the "state" of this society will

will

vary between these two

be represented by

S(

e {D,N},

regime that applies at that date. Importantly, irrespective of

political

the political regime (state), the identity of landowners and workers does not change; the

M individuals control the land, and have the potential to exercise additional

Overall political power

power. Since there

is

is

political

determined by the interaction of de facto and de jure

a continuum of

citizens,

power.

political

they will have difficulty in solving the collective

we

action problem to exercise de facto political power. Consequently,

as being exogenous rather than

same

stemming from

their

own

treat their de facto

power

contributions.

In contrast, elites can spend part of their earnings to gather further de facto political power.

In particular, suppose that

elite

Then

increasing their group's de facto power.

Zt

—

Y2ie£

^t

'

^^^

assume that

"^6

>

(p

The reason why

0.

their de facto political

activities is that there

that their

An

own

is

a finite number,

activities will

for the elite is the

Even though the

is

(13)

choose to spend a positive amount on such

of them, so each of

them

will

take into account

same

in

is

that the technology for generating de facto political

democracy and nondemocracy.^"*

citizens cannot solve the collective action

problem to invest

facto political power, since they form the majority in society they always possess

power.

The

be

contribution to total spending, Zt, will have an effect on equilibrium outcomes.

important assumption implicit in (13)

power

M,

power

on such

</>Zt,

may

the elite

as & contribution to activities

total elite spending

Pf =

where

9\>Q

^ £ spends an amount

i

extent of this power depends on whether the political regime

nondemocratic.

We

model the

citizens' total political

power

in

is

in their

some

de

political

democratic or

a reduced-form manner as

follows:

Pf =

"There may be a number

taries

may be more

of reasons for

why

ujt

+

vl

{st

= D)

,

(14)

the ehte's ability to lobby and bribe politicians or use paramili-

restricted in democracy, so in Section 4,

and nondemocracy.

10

we allow

this technology to differ

between democracy

where

is

utt

distribution

Sj

=

a random variable drawn independently and identically over time from a given

F {)

and measures

D, such that I

measuring

citizens'

= D) =

[st

I

while /

[st

— N) =

and

0;

n

is

rj

is

an indicator function

for

strictly positive pai'ameter

de jure power in democracy.

There are two important assumptions embedded

facto pohtical

— D)

their de facto power; I {st

power of the

The second assumption

is

and

citizens fluctuates over time,

that

when

The

in equation (14).

the pohtical regime

hard to predict

is

democratic,

is

first is

i.e.,

in advance.-'^

=

St

that the de

D,

citizens

have greater political power. This represents in a very simple way the fact that democracy

allocates de jure political

power

in favor of the majority.

This

will

be both because of the

formal rules of democracy and also because in democratic politics, parties

Put

the collective action problem of the citizens.

democracy the

To

stochastic dominance.

Assumption

power of the

political

F

2

is

simplify the discussion,

defined over (w, oo) for

everywhere).

w* such that

/' (w)

lim^^^cxD

=

/

(i^)

All of the features

Moreover, /

>

for all

partly solve

equation (14) implies that in

citizens shifts to the right in the sense of first-order

uj

{cu)

we make the

some w <

twice continuously differentiable (so that

/', exist

differently,

may

its

is

0, is

following assumptions

everywhere

on F:

strictly increasing

and

density / and the derivative of the density,

single

< w* and

peaked

<

/' (w)

(in the sense that there exists

for all

ui

>

uj*)

and

satisfies

0.

embedded

in

Assumption

2 are for convenience,

and how relaxing them

affects the equilibrium is discussed below.

We

introduce the variable nt G {0, 1} to deiiote whether the elite have more (total) political

power. In particular,

and

will

more

make the key

political

decisions are.

We

ttj

—

t,

and the

In contrast, whenever

will

make

description of the environment,

Tt,

and what the

Pf <

elite

Pf,

have more political power

nt

=

I

and

citizens have

the key decisions.

assume that the group with greater

institutions at time

When

decisions.

power, and they

To complete the

sions,

when Pf > Pf, we have

political

it

remains to specify what these key

political

power

will decide

both economic

regime wih be in the following period, St+i-

the elite have more political power, a representative elite agent makes the key deci-

and when

citizens

have more political power, a representative citizen does

political preferences of all elites

and

all

so.

Since the

citizens are the same, these representative agents will

always make the decisions favored by their group.

is used extensively in Acemoglu and Robinson (2006a), and defended there. Briefly, given

whether and how effectively citizens will be able to organize is difficult to predict in advance,

change from time to time. The randomness of ujt captures this in a simple way.

'"This assumption

their large numbers,

and

will

11

Timing of Events

2.3

We now

environment.

briefly recap the timing of events in this basic

At each date

t,

society starts with a state variable

G {D, N}. Given

St

the following

this,

sequence of events take place:

1.

Each

power

political

2.

agent

elite

£ £ simultaneously chooses how much to spend to acquire de facto

i

>

for their group, 9]

The random variable cot

0,

and

drawn from the

is

Pf

determined according to

is

distribution F,

and

(13).

Pf is determined according

to (14).

3.

4.

If

Pf > Pf

(i.e., TTt

—

a representative

0),

Pf < Pf

—

randomly chosen)

(e.g.,

elite

agent chooses

(Tt,st-|_i),

and

Given

transactions in the labor market take place, Rt and Wt are paid to elites and

r^,

if

(i.e., Tit

1),

a representative citizen chooses (rt,St+i).

workers respectively, and consumption takes place.

5.

The

following date,

i

+

starts with state st+i-

1,

Analysis of Baseline

3

We now

Model

analyze the baseline model described in the previous section.

symmetric R-Iarkov Perfect Equihbria (MPE).

strategies are

mappings from payoff-relevant

particular, in

an

MPE

above the influence of

this past history

(tt)

and

.

s' (tt)

and equilibrium

political power,

^ for

elite

Symmetric

form 6

s'

(n)

MPE

(s), i.e.,

€

{D,N}

s

G {D,N}. In

on the past history of the game over and

s.

An

MPE will

consist of

agent as a function of the political state, and

as a function of

tt

factor prices as given

6

{0, 1}

by

denoting which side has more

Here the function r

(8)-(ll).-^^

determines the equilibrium decision about labor repression conditional on

the function

focus on the

imposes the restriction that equilibrium

on the payoff-relevant state

each

first

which here only include

states,

strategies are not conditioned

contribution functions {^' (s)}

decision variables r

An MPE

We

(tt)

who has power and

determines the pohtical state at the start of the next period.

will in addition

impose the condition that contribution functions take the

do not depend on the identity of the individual

elite,

i.

Symmetry

is

a natural

since

it is

(tt, 5) and s' {n,s), so that the choice of economic institutions and future

on which party has political power, tt, and the current state, s. Nevertheless,

clear that the current state will have no effect on these decisions, we use the more economical notation

T

and

s' {n).

^^More

generally,

we could have r

political institutions are conditioned

(tt)

12

We

feature here, and simplifies the analysis.

A

more formal

The

focus on

elite

AiPE

MPE

is

the

elite.

MPE

completeness telow.

for

also given below.

natural in this context as a

is

among

action problem

the

an

definition of

discuss asymmetric

Looking

at

way

subgame

of

modehng

the potential collective

perfect equilibrium (SPE) will allow

greater latitude in solving the collective action problem by using implicit punishment

strategies.

We

briefly analyze

SPEs

in subsection 3.3.

Mciin Results

3.1

The

date

MPE can be characterized by backward induction within the stage game at some arbitrary

t,

given the state s 6 {D, TV}. At the last stage of the game, clearly whenever the

political power,

and a

political

whenever

i.e., tt

=

0,

they will choose economic institutions that favor them,

system that gives them more power in the future,

citizens have political power,

i.e.,

tt

=

1,

=

s'

i.e.,

=

they will choose r

i.e.,

r

have

=

0,

In contrast,

A''.

1

elite

and

s'

=

D}'^

This implies that choices over economic institutions and political states are straightforward.

Moreover the determination of market prices under

been specified above

(recall

equations (8)-(ll)).

different

Thus the only remaining

contributions of each elite agent to their de facto power,

be summarized by a

to characterize the

V (A)

for

d].

MPE

by writing the payoff to

elite

agents recursively, and for this reason,

value of an elite agent in state s by

V {s)

(i.e.,

V {D)

to 6 (A). Consequently,

i E.

when agent

have political power

P^

We

{e\

MPE,

democracy

suppose that

£, have chosen a level of contribution to de facto

i

E £ chooses

6^,

their total

power

P^ {9\e{N)\N)^cj){{M-l)e{N) +

elite will

for

nondemocracy).

other elite agents, except

The

MPE can

be convenient

(s). It will

Let us begin with nondemocracy. Since we are focusing on symmetric

all

decisions are the

Therefore, a symmetric

level of contribution as a function of the state

we denote the equilibrium

and

economic institutions has already

will

power equal

be

9').

if

9{N)\N)

=(l)

((M -1)9 (A) +

9')

>

wj.

is the same in

and s' = N. Throughout, we

use the tie-breaking rule that, when indifferent, citizens choose s' = D, and we impose this in the analysis.

Alternatively, in Section 5, equation (49) introduces more general preferences for the citizens, whereby they

receive other benefits from democracy, denoted by v{D). In that case for any u (D) > 0, s' = D is always

strictly preferred for the citizens. We do not introduce these preferences now to simplify the analj'sis until

will see in

Proposition

1

democracy and nondemocracy, so

Section

that the equilibrium distribution over economic institutions

citizens will

be indifferent between

5.

13

s'

=

D

Expressed

differently, the probability that the ehte will

have political power in this state

p{0\eiN)\N)=F{4>{{M-l)e{N) +

We

can then write the net present discounted value of agent

i

is

9^)).

(15)

e £ recursively as

= max I -9' +p(9\e{N)\N)(^ + l3ViN\e(N), 9(D))]

V{N\e{N),9{D))

'

e'>o

M

\

t

J

+ {l-p{9\9[N)\N)) (^^+13V{D\9{N),9{D))^Y

where

is

R^

recall that

is

the rate of return on land in competitive markets, given by

(9)

(16)

and K^

The

the rate of return on land under labor repressive economic institutions, given by (11).

function

V {N

when

other elite agents choose contributions 9 {N) in nondemocracy and 9 (D) in democracy.

all

V {D

Similarly,

The form

{N) 9 (D)) recursively defines the value of an

9

\

\

{N) 9 (D))

9

,

given his contribution

remain

will

the value in democracy under the same circumstances.

is

of the value function in (16)

because of the expenditure

in the

9^

0'',

is

intuitive. It consists of the forgone

plus the revenues and the continuation values.

and those of other

hands of the

agent in nondemocracy

elite

,

elite

institutions will be labor repressive,

elite

In particular,

agents in nondemocracy, 9 {N), political power

with probability p [9\d {N)

and

consumption

this elite agent receives

|

A'')

,

which case economic

in

revenue equal to K" L/M (rate

L/M) and

of return under labor repressive economic institutions, BJ' times his land holdings,

,

the discounted continuation value of remaining in nondemocracy, jiV

probability

— p [9\9{N)

1

and labor markets are competitive. In

to

R^L/M

Agent

i

change the

E £ chooses

9^

to

g

pTV

j^

Since

is

p (0\ 9

^^^

F

^

^^>jj

-g g^j^

\

political

maximize

pohcy function (correspondence)

Qi

this case a

and continuation value j3V [D

citizens will choose to

for the

\

(N) 9 {D)). With

9

,

9 (TV)

,

member

9 {D)), since with

system to St+i

his net

power

in their hands, the

D.

expected present discounted

maximization

optimal policy

—

(TV)

TV),

in (16)

be

T^

[9

{N) 9

,

utility.

(£*)],

Let the

so that- any

for the value function in (16) (in state s

which implies a particularly simple

1

of the elite receives revenue equal

—

TV).

continuously difTerentiable and everywhere increasing (from Assumption

is

=

have greater political power, so they choose r

TV), citizens

\

{N

2), so

first-order necessary condition for (16):

I

4>f{cP{{M-l)9{N) +

9'))

(^^ + (3(V{N\9{N),9{D))-V{D\9iN),9iD)))^

<

1,

(17)

and

(12),

0*

>

0,

and /

^*That

is,

with complementary slackness,'^ where

is

recall that

AT?

=

R^ —

the density function of the distribution function F. Moreover,

either 5'

=

or (17) holds as equahty.

14

R"^ is

it is

defined in

clear that

we

need the additional second-order condition that

wliy the maximization problem for individual

6'

that

V (N

does not affect

maximand

is

any

differently,

9^

consumption, which

which

from

this contribution,

more

political

6*'))

<

in this recursive formulation

V [D

{N) ,9{D)),so

9

\

The reason

0.-^^

is

so simple

is

differentiability of the

from

this political power,

focusing on a symmetric

de facto power by the

(17)

,

first-order condition

side of (17),

citizens,

which

ARL/M plus

(N) 9 [D)] must solve

is

and

satisfy the correspond-

quite intuitive:

must be equal to

the cost of forgone

(or less than) the benefit

the marginal increase in the probability of the

is

power than the

[9

hand

the right

is

T^

e

The

ing second-order condition.

in

i

+

1)9 {N)

guaranteed.

Expressed

direct benefit

(N) ,6 (D)) or

9

\

—

/' (0 (^{M

is

i.e.,

(pf

{•),

elite

and the benefit that the agent

will derive

the second term on the left-hand side, consisting of the

the benefit in terms of continuation value. Moreover, since

MPE,

9^

having

>

is

>

equivalent to 9 {N)

0,

so

if

there

is

we

are

any investment

then (17) must hold as an equality.

elite,

Next, consider the society starting in democracy. With the same argument as above, the

elite will

have political power

P^

which only

differs

if

9{D)\D)^ct> {{M -1)9 {D) +

{9\

from the above expression because with

tional advantage represented by the positive parameter

will

capture political power in democracy

p {9\

=

+

ut

D, the

Then the

rj.

77,

citizens

have an addi-

probability that the elite

1) e

+ 9') -

{D)

ry)

(18)

,

as before, the value function for elite agent

i

£ £

is

= max!.-9'+p(9\9{D)\D)(^ + f3V{N\9{N).9{D))

V{D\9{N),9iD))

which has

st

>

is

9{D)\D)=F (0 ((M -

and using the same reasoning

9')

w>o

[

+

-p{9\9{D) D))

(1

'

\

M

\

+ PV (D

(^^

\9

iN),9{D)))\

(19)

first-order necessary condition

cpf{cp{{M-l)9{D) +

9')-il)(^^ + /3{V{N\9{N),9{D))-V{D\9{N),9{D)))) <

1,

(20)

and

/'

0'

[(f>

>

0,

((M —

again with complementary slackness and with second-order condition

1)6' (A'^)

+

0')

—

the maximization in (19) by

'"The condition /' (0 ((M

necessary but not sufficient.

?])

T^

<

[9

0.

Denote the policy function (correspondence) imphed by

(N) 9 (D)], so that any

,

-1)9 {N) + 9')) <

We

impose the

is

sufficient,

sufficient condition

15

9'

6

T^

[9

[N)

,

9 {D)] solves (20).

< would be

{(j> ((M -1)6 (N) + 9'))

throughout to simplify the discussion.

while /'

Consequently, denoting the decision of current economic institutions by r

system by

political

Definition 1

e

A

we can have the following

s' (tt),

MPE

symmetric

T^

[9

0)

— N,

T

=

{tt

=

1)

1

and

5' {tt

—

T^

(N) 9 (D)] and similarly 9 {D) e

,

In addition, economic and political decisions r

=

symmetric MPE:~°

consists of a pair of contribution levels for elite agents

(N) and 9 (D), such that 9 {N) e

s' {tt

definition of a

and future

(tt)

I)

=

(tt)

and

D, and

s' (tt)

[9

are such that t

factor prices are given

(N) 9

,

{tt

by

—

0)

(D)].

—

0,

(8)-(ll) as a

function of r € {0, 1}.

This definition highlights that the main economic actions, in particular, the investments

by

in de facto power, are taken

elite agents,

so the characterization of the

MPE

will involve

solving for their optimal behavior.

MPE,

In a symmetric

9 {N)

,

must be given

9^

that solves (17) must equal 9{N), thus

{^ +(5V{N\9{N),9

and similarly the equilibrium condition

{<PM9 {D)

Given Definition

and 9 {D) >

-

1,

strictly positive,

by:

0/ {cf>M9 {N))

4>f

when

r/)

for 9

{D))

-

{D) (when

(iV

{D \9{N)

,9

{D))^

=

1,

(21)

=

1.

(22)

strictly positive) is

(^^ +PV{N\9{N),9 {D)) -PV{D\9{N),9 {D))\

these two equations completely characterize symmetric

MPEs with 9 (TV) >

0.

Comparison

of (21)

and

(22)

immediately implies that

9{D) = 9{N)

Moreover inspection of

(21)

and

(22),

+

^.

combined with the

(23)

fact that

F

is

continuously difFeren-

tiable, yields the invariance result:

p{D)=p{9{D),9{D)\D)=p{9{N),9{N)\N)=p{N),

which also defines p {D) and p {N) as the respective probabilities of the

taining) political

Intuitively, in

power that they

power

in

(tt)

and

democracy the

elite invest sufficiently

more

entirely offset the advantage of the citizens

s' (tt),

gaining (or main-

democracy and nondemocracy.

^"This definition incorporates the best responses of

tutional, T

elite

(24)

elites

for convenience.

16

to increase their de facto political

coming from

their de jure power.

and citizens regarding economic and political

insti-

A

more

technical intuition for this result

is

that the optimal contribution conditions for elite

agents both in nondemocracy and democracy equate the marginal cost of contribution, which

is

always equal to

1,

to the marginal benefit. Since the marginal costs are equal, equilibrium

The marginal

benefits in the two regimes also have to be equal.

ARL/M,

mediate gain of economic rents,

benefits consist of the im-

plus the gain in continuation value, which

also

is

independent of current regime. Consequently, marginal costs and benefits can only be equated

a p{D)=p{N)

It is also

as in {24).

straightforward to specify

when there

In particular, the following assumption

be positive investment in de facto power.

will

sufficient to

is

ensure that the equilibrium will have

positive contribution by elite agents to de facto power:

Assumption 3

ARL]

,,„, ARL

,,

mm|^/(O)^^,0/(-^)-^|>l.

.

Since

this

V (N) — V {D) >

r

,

,

,

,

(by virtue of the fact that the elite choose nondemocracy),

assumption ensures that in both regimes, an individual would

contribution even

if

nobody

also exist equilibria in

else is

which the

doing

elite

assumption

If this

so.^^

make no

is

like to

make a

positive

may

not satisfied, there

contribution to increasing their de facto power

(see Corollary 1).

Proposition

1

(Invariance) Suppose Assumptions

there exists a unique symmetric

MPE.

1-3 hold.

is

=

and 6

Since Assumption 2 implies that / (w)

The

comparison of these two

follows from

Assumption

result that

equalities,

2,

isfy (21)

and

Assumption

2,

/ (w)

is

p {D)

=

p (N)

F

is

F {4>Me [D) -

(A^)

some

which establishes

which imposes that

so for any interior 9 {D) and 9 {N),

from Assumption

6 (0,1), so

non- degenerate and independent

=

cannot be part of an equi-

continuous and lim^^^oo /

is

conditions (21) and (22) must hold as equalities for

establishing existence.

is

— p{N)

model,

democratic or nondemocratic.

Proof. Assumption 3 ensures that 6 {D)

librium.

in the baseline

This equilibrium involves p{D)

that the probability distribution over economic institutions

of whether the society

Then

>

interior values of 9

(24).

The

fact that

3 also implies that

ry

< — oj

<

and

(where

/'

^ F {(pM9 {N)) <

{(pM9 {D)

recall that

17

w <

0,

both

{D) and 0{A^),

-

77)

0); see

<

p{D)

= p{N) <

throughout

single peaked, so only a unique pair of 9 (D)

(22) with /' {(f>M9 [N])

=

then follows immediately from the

strictly increasing

i])

(^')

1.

its

1

support,

In addition, again

and 9 {N) could

for given

sat-

V (N) - V {D).

condition (26) below.

The

V (N) — V {D) —

fact that

i]/ {(f)M)

estabhshes the uniqueness of the symmetric

This proposition

is

uniquely determined (from equation (24)) then

is

MPE.

one of the main results of the paper.

shows that there

It

librium changes from democracy to nondemocracy and the other

the fact that the equihbrium probability distribution

non-degenerate,

is

(this follows

i.e.,

of de jure power, but they

do not translate into changes

tutions and economic allocations,

invariance in equilibrium; even

p{D) = p[N) e

i.e.,

in the

we have p [D) — p

law of motion of economic

{N)?"^ This

when shocks change the

insti-

the sense in which there

is

political institutions, the probability

distribution over equilibrium economic institutions remains unchanged. This result also

trates

from

Moreover, by assumption these changes in political institutions affect the distribution

(0, 1)).

is

way round

be equi-

will

how

institutional change

and persistence can coexist

—while

illus-

change

political institutions

frequently, the equilibrium process for economic institutions remains unchanged.

Remark

1

As

will

be discussed further below, the invariance

assumptions. Section 4 will show that

de facto power

for the elite in

when

Other assumptions implicit

result are: (1) that

on functional form

there are differences in the technology of generating

democracy and nondemocracy or when economic

costly to change in the short run, de facto

partially.

result relies

democracy

power

will only offset the

in our analysis that are

shifts the

power of the

change

institutions are

power

in de jure

important for the invariance

than

cj

being

Fq

first-

order stochastically dominating F/v); (2) that the technology of de facto power for the

elite,

drawn from general

equation (13),

is

nondemocracy and Fp

distributions F/v in

linear.

When

citizens additively (rather

in

democracy, with

either of these assumptions are relaxed,

we continue

to obtain

the general insight that endogenous changes in de facto power (at least partially) offset declines

in the

de jure power of the

Remark

elite,

but not necessarily the invariance

1.

For example,

sions in Proposition

1

if

we

relax the single-peakedness assumption

would continue to apply, except that the symmetric

be unique. Multiple equilibria here are of potential

which expectations of future behavior

if

relaxed,

See Section

4.

2 Assumptions 2 and 3 can be relaxed without affecting the basic conclusions in

Proposition

Also,

result.

affects current

the parts of Assumption 2 that

we may obtain corner

transitions to

from investing

F

solutions,

is

behavior

whereby p{A^)

the conclu-

MPE may no longer

they correspond to situations in

(see, e.g.,

Hassler et

= p[D) =

(essentially

1,

al.,

when

18

total

2003).

=

because returns to individual

power

shifts

are

and there would be no

power may remain high, while the probability of a

'Yet, naturally, economic institutions will change

(cj),

increasing everywhere and limu,^oo / (w)

democracy from nondemocracy

in de facto

interest, as

on /

elites

sufficiently high

from one group to another.

level of

LJ

becomes

(^N)

=

p {D)

result

is

interesting in this context.

p

Corollary

1

=

Alternatively,

0).

Assumptions

0.

Suppose there

that Assumptions

1

and

2

Assumption 3

if

and 3

exists ^(A'')

2 hold,

>

equilibria with

The

following

such that

and that

> -u.

(26)

model, there exists a symmetric

in the baseline

we can have

relaxed,

rule out these "corner" equilibria.

r?

Then

is

MPE in which p (N)

G

(0, 1)

and p {D)

—

0.

Proof. Suppose there

R^L/

{{1

—

P) M), while V"

{N)

condition for

obtain

exists a

e{N) =

>

is

(A'')

Now

using (21) and (22),

to de facto power in

/

(-77)

=

0,

'

we

(

jj^

^

Combining

this

Then we have

0.

with the expression

^ F[cj>Me{N))^RL/M -

'

V (D) =

V {D),

for

see that (25)

nondemocracy

is

e[N)

sufficient to ensure that positive contribution

is

optimal for

elite agents.

Moreover, (26) implies that

thus

F (—77) =

p{D) = 0. m

(26),

Therefore,

sorbing state

when

0,

if

we relax part

may

rj

is

is

also optimal for the elite.

which establishes the existence of a symmetric

arise.

of

Assumption

3,

Clearly, Condition (26),

high. This implies that

in favor of the citizens,

it

may

if

symmetric

Moreover, again from

MPE with p (N)

MPEs

e

(0, 1)

which leads to this outcome,

is

more

likely

democrac}' in fact creates a substantial advantage

destroy the incentives of the

elite to

engage

in activities that

and

institutions.

It is also

p {D)

and

with democracy as an ab-

increase their de facto power, and thus change the future distribution of political regimes

economic

we

- PF{(pM9{N))

I

so that zero contribution in democracy

to hold

=

and

y

y (j^n

with p [D)

given by (16), and the relevant first-order necessary

given by (21).

9 {N) as in (25),

^

still

is

MPE

symmetric

interesting to note that even

— p {N) >

when Condition

characterized in Proposition

1

19

may

(26) holds, the equilibrium with

still exist,

leading to a symmetric

MPE

= p (N).

with p {D)

Consequently, whether democracy becomes an absorbmg state

may depend on

consolidated),

expectations.

Finally, inspection of the proof of Corollary 1

Assumption

With

3

A

There

exists

tion 3 since, despite being

Non-Symmetric

3.2

We now

more

do

this,

we

first

is

and

the results continue to hold, though

restrictive,

it is

to:

we

prefer

Assump-

simpler and more transparent.

MPE

result obtains without the restriction to

MPE

extend our treatment above and define an

Without symmetry, the power

i

all

shows that Assumption 3 can be relaxed

satisfying (25),

show that the same invariance

MPE. To

agent

0{N) >

assumption,

this modified

fully

(i.e.,

of the elite in

nondemocracy

£ £ and the distribution of contributions by

all

symmetric

more

generally.

as a function of contribution

other agents, 9~' (TV)

=

{^-^

by

6'^

{N)] .^

.

,^,

given by

Similar to before, in nondemocracy the elite will have political power with probability

p{e\e-^{N)\N)^F[<p(

In democracy, with the

same reasoning

0^{N)

+ 6A\.

as before, this probability

p{9\e-^[D)\D)^F(<pi

V

The

E

E

given by

is

+ e^\-7A.

9^[D)

\j?:£,]¥^^

J

elite implies

be indexed by

i.

that value functions can also differ across

(28)

J

possibility that different individuals will contribute different

power of the

(27)

amounts

agents,

elite

Therefore, the net present discounted value of agent

i

to the de facto

G

and must

£^ is

V'{N\9'^{N),e-'{D))

= max

9'

+ {l-p{9\9-'

Here

elite

V (TV

|

_,

+ p {9\ 9-'

{N)

,.„

(29)

,

(N)

...

N)

.

i

I

TV))

I

also

R'L

——

+ 13V' {N

(^ +/3V^ {D

0"' (TV) ,0~' (D)) denotes the value of agent

9'' (TV)

9-' (A^)

,

0-

I

i

in

agents choose contributions 9"' (N) in nondemocracy and

20

\

,

9-' (D))

(Z?)))

|

.

nondemocracy when

9"''

(D)

in

all

other

democracy. Similarly,

9~^ (N)

V^ (D

,

0^' (D))

the corresponding value in democracy for agent

is

equation

for this

Agent

is

£ £ chooses

i

6^

maximize

to

{N) 0-' (D)] so that any

[e-'

symmetric

similar to that for (16) in the

his net

pohcy function (correspondence) of agent

rf

i.

The

intuition

I

,

€

6'

,

expected present discounted

utility.

Let the

that solves the maximization in (29) be given by

i

[9''

{N) 9"' (D)]

is

,

an optimal policy

the value

for

we have

function in (29). Similarly,

9'' {N)

V' [D

Pf

case.

,

9-' (D))

(30)

I

= m^L9'+p{9',9~^{D)\D)(^^+pv'{N\9-HN),9-'{D))'^

+ {l-p {9\ 9-^

and

the set of maximizers of this problem be

let

general definition of

Pf

MPE

that r

(tt

=

0~' (Z?)]

,

,

0)

=

9-^ (D)))

I

{N) 9~^

[9~^

,

(L>)]

Then we have the more

.

i

e

S, 9'

{N) G

Pf

for elite agents

0, s' (tt

=

=

0)

A',

r

(tt

=

—

1)

1

[9'^

i^)}ip£

[9'' {N) ,9'' {D)] and similarly 9' {D) G

In addition, economic and political decisions r

.

|

as:

{9' (D)}^^^, such that for all

[(9~' (A'^)

Ff

{D r' [N]

An MPE consists of a pair of contribution distributions

Definition 2

and

\D))[j^+ aV^

(D)

and

=

s' (tt

1)

=

and

(tt)

are such

s' (tt)

D, and factor prices are

given by (8)-(ll) as a function of r £ {0, 1}.

Proposition 2

Then

(Non- Symmetric

in the baseline model,

any

MPE and Invariance)

MPE involves p (D) = p (A)

Suppose Assumptions 1-3 hold.

G

(0, 1).

Proof. See Appendix.

The only

we

know

also

that the total contributions

agents

elite

between symmetric and non-symmetric

In non-symmetric

elite agent.

some

difference

may be

MPE,

expected

implies that in non-symmetric

this

may

the

elite will

in

symmetric

MPE

be equally divided among each

not be the case, and depending on expectations,

and consequently do, contribute more than others. This

to,

MPE,

made by

MPE is that

different levels of

p (D)

= p (A)

can

arise in equilibrium.

Nevertheless, the important conclusion that the probability of the elite dominating political

power and imposing

form of

political institutions remains.

symmetric

MPE.

CoroUciry 2

ff'

(D)

their favorite

=

9''

Before doing

so,

economic institutions

Given

+

ri/(f),

and

for

independent of the underlying

this result, in the rest of the

paper we focus on

however, we can also note the following result:

Among non-symmetric MPEs,

(A)

is

alH G ^ and

the following maximizes p (A)

i

7^

21

i\ 9'

{D)

=

9'

(A)

=

0.

= p (D):

for

i'

G

S,

The proof

Proof.

dition (59) in the

i

Appendix holds

(61-"'

{N),e-' (D))

(D))

=

that an equihbrium with

9''

AV'

and

(e-'' {N),e-''

^

i

note

exists,

i'

AV'

have

(0"'

(ct>

any such

(9^'

9''

+

(N)

i'

for

alH G

for

ri/cf)

—

(A)

9''

and

£"

i

and

z'

j^

9''

(A)

+

i

(A)) )=</./ (0

e

-

r?)

fARL

=

[-^

(D))

[9^'

-

7?)

<

i'

achieves the highest

and

9'

p (A)

{D)

=

=

(A)

9'

= p (D) among

Intuitively, the equilibrium that

de facto power means that