Document 11157852

advertisement

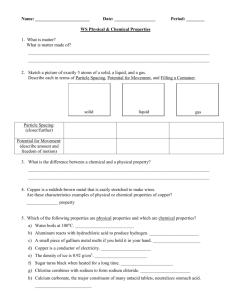

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/copingwithchiles00caba2

c

L

j

15

oi-

I

3

'-1^

Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Massachusetts

Institute of

COPING WITH CHILE'S EXTERNAL VULNERABILITY:

A FINANCIAL PROBLEM

Ricardo

J.

Caballero

WORKING PAPER

01-23

REVISED, January 2002

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Diive

Cambridge,

MA 021 42

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

This

http://papers.ssrn.

o m/abstract=274083

Dewey

\(y

Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Massachusetts

Institute of

COPING WITH CHILE'S EXTERNAL VULNERABILITY:

A FINANCIAL PROBLEM

Ricardo

J.

Caballero

WORKING PAPER

01-23

REVISED, January 2002

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge, MA 02142

This

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http://papers.ssrn. conn/abstract=274083

'.GHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OFTECHMOLOGY

H'AR

7 2002

LiBF?ARiES

Coping with Chile's External Vulnerability:

A Financial

Problem

01/11/2002

Ricardo

J.

Caballero'

Abstract

With traditional domestic imbalances long under control, the Chilean business cycle

Most

driven by external shocks.

A

financial problem.

a decline

in real

importantly, Chile

's

external vulnerability

decline in the Chilean terms-of-trade, for example,

GDP that is many times larger than

one would predict

is

is

is

primarily a

associated to

in the presence

of

perfect financial markets. The financial nature of this excess-sensitivity has two central

dimensions: a sharp contraction

it

needs

it

the most;

and an

borrowers during external

and argue

Chile's access to international financial markets

in

crises. In this

paper I characterize

that Chile's aggregate volatility can

this

financial mechanism

be reduced significantly by fostering the

private sector's development offinancial instruments that are contingent on Chile

external shocks.

As a

when

inefficient reallocation of this scarce access across domestic

first step, the Central

Bank or

IFIs could issue a

's

main

benchmark

instrument contingent on these shocks. I also advocate a countercyclical monetary policy

but mainly for incentive

— that

is,

as a substitute for taxes on capital inflows and

equivalent measures — rather than for ex-post

'

MIT

Banco

Loayza

and

NBER.

e-mail: caball(a)mit.edu; http://web.mit.edu/caball/www.

Central de Chile.

for their

liquidity purposes.

I

comments;

am

to

Prepared for the

very grateful Vittorio Corbo, Esteban Jadresic, and

Adam Ashcraft, Marco

for excellent research assistance;

and

required data. First draft: 03/06/2001.

to

Norman

Morales and especially Claudio Raddatz

Herman Bennett

for his effort collecting

much of the

Introduction and Overview

I.

With

domestic imbalances long under control, the Chilean business cycle

traditional

extemal shocks. Most importantly, Chile's extemal vulnerability

A decline

is

many

Chilean terms-of-trade, for example,

in the

is

is

driven by

is

primarily a financial problem.

GDP that

associated to a decline in real

times larger than one would predict in the presence of perfect financial markets. The

of

financial nature

this excess-sensitivity

has two central dimensions: a sharp contraction in

when

Chile's access to international financial markets

needs

it

it

the most;

reallocation of this scarce access across borrowers during extemal crises.

I

and an

inefficient

argue that Chile's

aggregate volatility can be reduced significantly by fostering the private sector's development of

on the main extemal shocks faced by

financial instruments that are contingent

Bank

step, the Central

—

that

is,

a

first

or IFIs could issue a benchmark instrument contingent on these shocks.

also advocate a countercyclical

incentive

As

Chile.

I

monetary pohcy (also contingent on these shocks) but mainly for

as a substitute for taxes

on

and equivalent

capital inflows

— rather than for

ex-post hquidity purposes.

The essence of the mechanism through which extemal shocks

be characterized as follows:

First, there is

for extemal resources if the real

economy

latter

to continue unaffected, but this triggers exactly the

who puU back

capital inflows. Occasionally, the

occurs directly as part of "contagion" effects. Second, once extemal financial markets faU

accommodate

the needs of domestic fiimis and households, these agents turn to domestic

financial maricets,

and to commercial banks in

matched by an increase

domestic

in supply as

banks

as

—

firms find

large

it

more

financial markets at

crisis,

of

this

any

when major

crisis is

to

is

not

tighten

are high.

Widespread

forced adjustments are needed.

rise

a

Limit

is

seek financing in domestic markets, in

medium

size firms cannot access intemational

in

expected returns,

symptom of these

The sharp

decline in domestic asset prices,

driven by the extreme scarcity in financial

is

Even

financial constraints are binding during the

the praised rise in

fire sales.

The

FDI

Chile's

integration to

that

occurred during the

fact that this investment takes the

control-purchases rather than portfoUo or credit flows simply reflects

that

-

domestic financial system, which reinforces the above

resources and their high opportunity cost.

problems

demand

price.

mechanism

and corresponding

most recent

Again, this increase in

particularly resident foreign institutions

attractive

circumstances that the displaced small and

costs

particular.

opting instead to increase their net foreign asset positions. Third, there

credit,

significant "flight-to-quaUt}^' within the

effects

The

Chilean economy can

a deterioration of terms-of-trade that raises the need

is

opposite reaction fi^om international financiers,

to

affect the

intemational

financial

markets:

weak

corporate

governance and other "transparency" standards. Finally, the costs do not end with the

financially distressed firms are iU

form of

some of the underlying

equipped to mount a speedy recovery. The

latter

crisis,

often

as

comes

not only with the costs of a slow recovery in employment and activity, but also with a slowdown

in the process

of creative destmction and productivity growth. In the U.S., the

account for about

1998),

which

is

30%

latter

may

of the costs of an average recession (see Caballero and Hammour,

probably a very optimistic lower bound for the Chilean economy. Moreover,

number of

the presence of a large

when

financially distressed small firms,

severe enough,

reduces rather than enhances the effectiveness of monetary policy in facihtating the recovery

(see below).

The

distnbutional impact of this type of crisis

is

On

significant as well.

one end,

large firms are

directly affected by external shocks but can substitute most of their financial needs domestically.

They

by demand

are affected primarily

PYMES)

(henceforth,

are

are the residual claimants

factors.

On

the other, small

and medium sized firms

crowded out and are severely constrained on the

of the

financial crunch.

They

financial side.

-

This diagnosis points in the direction of a stmctural solution based on two building blocks. The

first

one deals with the

institutions required to foster Chile's integration to international financial

markets and the development of domestic financial markets. Chile

along this margin through

its

capital

the unavoidable slow nature of the above process,

liquidity

management

management of

strategy.

The

latter

intemational reserves

by

focus on the

latter

is

to design

must be understood

the central bank,

financial instruments that facilitate the delegation

I

is

making

significant progress

markets reform program. The second one, necessary during

an appropriate international

in terms broader than just the

and include the development of

of this task to the private

type of solutions in this paper.^

sector.

view the pohcy problem as one of

I

remedying a chronic private sector underinsurance with respect to external

outlining the

them. The

main sources of such problem and

first

the corresponding solutions,

one seeks to develop a key missing market.

benchmark "bond"

instalment should

that is

made

facilitate

contingent on the

main

I

I

After

crises.'

focus on

two of

propose the creation of a

external shocks faced

by

Chile. This

the private sector's pricing and creation of similar and derivative

contingent financial instruments.

In the second one,

I

discuss optimal monetary

poUcy and intemational reserve management

fi-om

an insurance perspective. Provided that the Central Bank of Chile has achieved a high degree of

inflation-target credibility, the optimal

response to an external shock

of reserves and an expansionary monetary pohcy. The

real

latter,

is

however,

with a moderate injection

is

unlikely to have a large

impact and indeed will imply a sharp short-Uved exchange rate depreciation. The main

benefit

of such pohcy

is

in the incentives

it

provides.

Its

main problem

it

is

time-

mechanism

at

work.

is

that

inconsistent.

Section

2

II

describes the essence of the extemal shocks and the financial

See Caballero (1999, 2001) for a discussion of the structural reforms aimed

the

development of financial markets. More importantly, Chile

is

in the

at

improving integration and

process of enacting a major capital

markets reform.

See Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2001a) for a formal discussion of this perspective.

.

Section in follows with a discussion of the impact of this

economy and

the different

economic

agents. Section

IV

mechanism on

discusses

the real side of the

pohcy options and Section

V

concludes.

The Shock and the Financial System

II.

In this section

economy.

I

illustrate the

mechanism though which

mechanisms around demand and supply

backbone of the Chilean

presented in

I

external shocks aflFect the Chilean

organize the discussion of the role played by these shocks and their amplification

I

Box

factors affecting the domestic

An

financial system.

banking system

overview of the Chilean financial

-

the

institutions is

1

focus on the most recent cychcal episode, as the changing nature of the Chilean financial

system makes older data

//.

1

less relevant.

The External Shock and its Impact on Domestic Financial Needs

The trigger of the mechanism

of-trade

instrument.

It is

apparent that Chile

(b) offers a better metric to

1996

is illustrated

in Figure

1.

Panel

(a)

shows the path of Chile's terms-

and the spread paid by prime Chilean instruments over the equivalent U.S. Treasury

cvirrent

was

severely affected

by both

at the

end of the 1990s. Panel

gauge the magnitude of these shocks. Taking the quantities firom the

account as representative of those that would have occurred in the economy

absent any real adjustment,

it

deterioration in terms-of-trade

and

translates

them

into

the dollar losses

interest rates. In 1998, these losses

of GDP, with similar magnitudes for 1999 and 2000.

associated to the

amounted

to about

2%

Box

The Chilean Banking

1:

Sector

Table A.2: Composition ofloansby use.

Banks

of financing

are an important source

Chilean

for

The

firms.

financing (table A.l)

is

and much

60%

similar to that of

Residential

the maturity

Trade

15%

10%

10%

US,

like the

more

Other

5%

of Chilean bank loans

structure

of total loans

Fracti(>n

Commercial

advanced European economies. Unlike the

latter,

Type of loan

of

composition

is

57%

concentrated on the short end:

Consumption

Source: Superintendencia de Bancos

of

e Instituciones

total

Financieras.

loans,

and

60%

of commercial loans, have a

maturity of less than

1

year.

summary,

In

Chilean banks look like European banks in

terms of their relative importance but

banks

of

terms

in

on

focus

their

like

US

Composition of commercial loans by

firm

size.

short

Chilean banks concentrate their lending

maturities.

on

activity

size

Relative importance: Loans versus

65%

Around

other instruments.

large fums, at least

approximated

is

of

commercial loans

above

Table A.l: The relative importance of bank

US$

different

1

.

loan

The

is

by

firm

size.

volume

the

of

allocated to loans

importance of

relative

sizes

when

loan

is

summarized

in

loans.

Source of financing

Stock

Flows

Loans

43%

54%

51%

33%

3%

16%

Equity

Bonds

Note:

Participations

December 2000.

using

built

Flows

were

stocks

the

computed

as

Table A.3.

Table A.3: The relative importance of

different loan sizes.

at

Loan

in stocks between December

1999 and

December 2000 except for the flow of new equity,

which was built using information on equity placement

during the period.

on

activity

Medium

Micro

Note:

represent around

(see Table A.2).

70%

and

most of

Commercial

60%

of

Adding

total

their

loans

of total bank credit supply

loans above 50,000

US$

UF

(around

of 1999 dollars)); Medium:

1,400,000); Micro: loans

UF (US$

280,000

below 10,000 UF

(US$ 280,000).

Source: Superintendencia de Bancos

e Instituciones

Financieras.

bank loans

is

directed to

Banks versus other

financial

institutions.

Computed using

Source

all

trade loans, about

firms.

''

Large:

1.4 millions (end

loans between 10,000 and 50,000

concentrate

firms.

64%

14%

22%

Large

US$

Composition of Loans.

volume of

commercial loans

the

difference

Chilean banks

Fraction of the

size

the stock of loans in

Superinlendencia

de

Bancos

December

e

1999.

Jns/i/imones

Financieras.

In Germany, for example, more that 70% of the

commercial loans are long term. In contrast, in the US

short term loans account for about 60% of non^

residential loans.

Banks in Chile are important when

compared with other financial institutions

as well. Table A.4 compares the total

assets

of banks,

pension

fiinds,

and

represent

Banks'

companies.^

insurance

60%

of

assets

total assets.

Table A.4: Banks and other financial

institutions.

Banks

Pensio

Insurance

n

companies

Funds

Relative

60%

30%

10%

asset level

Note: Ratios based on the stock of

assets

at

December 2000.

Sources:

Superintendencia

Bancos

de

e

Instituciones

Financieras, Superintendencia de Valores

y Seguros.

Domestic and Foreign banks.

banks

Foreign

presence

very

is

Table A.5 shows that loans

significant.

by foreign banks represented around

40%

of

total

loans

in

1999.

It

is

important to note that Chilean Banking

Law

does not recognize subsidiaries of

banks

foreign

as

part

of

main

their

headquarters.

Table A.5: Domestic and Foreign Banks

Relative importance

Domestic

Foreign

58%

42%

80%

11%

67%

(%) total loans)

Portfolio composition

Loans

Securities

Foreign assets

Reserves

14%

15%

6%

3%

4%

Note: Ratios based on December 1999 values.

Source: Superintendencia de Bancos

e Instituciones

Financieras.

Total assets

is

the

sum of financial and

fixed assets.

Fixed assets are not included for insurance companies.

Nevertheless, fixed assets represent a very small

fraction of financial institutions' assets.

'

Figure

(a) TefTTis ot

1:

External Shocks

Trade and Sovereign Spread

(b)

Terms

of

Trade and Interest Rate

effect (fixed quanlities)

I1U1MJ

~>

\

—

^

'

Vy

—

/

—

V

.

V V ^s

\

;\/ "

'

_

~

_

-

•^

<•

^

Hi

A

fi

Hi

1

y

-4

/

._ ^ •

.

.

^

/',

f

<

^'"'

i

1

I

i-

1

1.

i

TemaoltfjdB

[

\

'^

I

'^

\

i

s

s

1

i

i

1

?

s

1

— -St»B3dEntnaEr»tea|

H TT eHecl

li.rnri.sl

ram BffT^

Notes: Preliminary data used for 1999 and 2000. The yearly Figure for 2000 was computed multiplying the S quarters

cumulative value by 4/3. (a) Terms-of-trade

is

the ratio

of exports price index and import price index computed by the

ENERSIS-ENDESA corporate bonds. The spread data

Central Bank. The sovereign spread was estimated as the spread of

for 1996 was estimated by the author using information from the Central Bank of Chile,

computed as the difference between the actual terms-of-trade and the terms-of-trade

effect was computed in similar fashion

at

(b)

The terms-of-trade

1996

quantities.

effect

was

The interest rate

Source: Banco Central de Chile.

How

should Chile have reacted to this sharp decline in national income, absent any significant

financial friction (aside

The

from the temporary increase

thin line depicts the path

in the spread)?

Figure 2 hints the answer.

of actual consumption growth, while the thick

hypothetical path of Chile's consumption growth if

it

line illustrates the

were perfectly integrated to

international

markets and terms-of-trade the only source of shocks.' There are two interesting

financial

features in the figure. First, there is a very high correlation

shocks to

its

terms-of-trade. This correlation

is

between Chile's business cycle and

not observed in other

commodity dependent

economies with more developed financial markets, such as Australia or Norway (see Caballero

1999 or 2001). Second, and more importantly for the argument in

response of the

economy

measured on the

it is

is

being measured on the

right axis. Since the scale in the

apparent that the

economy

left

is

being

ten times larger than that of the

latter,

over-reacts to these shocks

by a

significant margin.

shocks to the terms-of-trade are simply too transitory, especially

demand

of the hypothetical

is

axis while that

former

this paper, the actual

when

as in the recent crisis, to justify a large response of the real side

In practice

they are driven by

of the economy.^ The

Consumption growth is very similar to GDP growth for this comparison. Adding the income effect of

shocks would not change things too much as these were very short-lived.

I

neglect the

presence of substitution effects because there is no evidence of a consumption overshooting once

interest rate

international spreads

come down.

income

measured

effect that is

of Figure

in panel (b)

practice, translate almost entirely in increased

Figure

2:

1

should in principle, but

it

does not in

borrowing from abroad.

Excess Sensitivity of Real Consumption

Growth

to

Terms-of-Trade Shocks

13BS

1SB7

PV^g^

af.Brtif<Wl7W.m«in)

I

Notes: consumption growth from IFS, copper prices (London

Metal Exchange) from Datastream, copper exports from Min.

de Hacienda.

Returning to the

late

1990s

crisis,

panel (a) of Figure 3

illustrates that international financial

markets not only did not accommodate the (potential) increase in demand for foreign resources

but actually capital inflows declined rapidly over the period. Panel (b) documents that while the

central

bank

clearly

was not

offset part

of

this decline

by

injecting

back some of

its

international reserves,

it

nearly enough to offset both the decline in capital inflows and the rise in external

needs. For example, the figure shows that in 1998, the injection of reserves amounted to

approximately

US$2

and

in terms of trades

inflows that

'

The

bilhon dollars. This

came with

is

comparable to the

but

rise in interest rates,

it

direct

income

effect

of the decline

does not compensate for the decline in capital

these shocks.

price of copper has trends and cycles at different frequencies,

some of which

are persistent (see

Marshall and Silva, 1998). But there seems to be no doubt that the sharp decline in the price of copper

during the late 1990s crisis was mostly the result of

and Russian

crises.

demand shock,

copper

1

would argue

demand shock brought about by the Asian

that the current shock was a transitory

the univariate process used to estimate the present value impact of the decline in the price of

in Figure 2, overestimates the extent

of this decline. The lower decline

with this view. The variance of the spot price

Moreover, the expectations computed from the

is

in future prices is consistent

6 times the variance of 15-months-ahead future prices.

AR process track reasonably well the expectations implicit in

future markets but for the very end of the sample,

play.

a transitory

on the information

that conditional

when

liquidity

premia considerations

may have come

into

Figure 3: Capital Flows and Reserves

(a) Capital

Account except Reserves

(b)

BabncE

of

Payments

ecoD

son

r

'i^'\

c-^

I

"EE

•1C00

-2.000

Source: Banco Centra! de Chile

How

severe

was

mismatch between the increase

the

financial resources? Figure

in

needs and the availability of extemal

4a has a back-of-the-envelope answer.

account (light bars) and the current account with quantities fixed

the trough, in 1999, the actual current account deficit

what one would have predicted using only

at

bars),

in panel (b),

at

1996 levels (dark

bars).

At

the actual change in terms-of-trade. Moreover, this

dollar adjustment underestimates the quantity adjustment behind

and the current account

graphs the actual current

was around US$4 bUhon smaller than

it,

of-trade typically worsens the current account deficit for any path

of this price-correction can be seen

It

as the deterioration of terms-

of quantities. The importance

which graphs the actual current account (hght

1996 prices (dark

bars).

Clearly, the latter

shows a

significantly larger adjustment than the former.

Figure 4: The Current Account

(a)

CunentAccajnt and CuiTent Account

at

(b)CunGnt Account

1996 quantities

(actual

and

h

19g6pnc8s}

S^

t599

M CjTtrt /•a

Notes:

(a)

USS\» Qjignt Arc |m« USl

2000

96il

The current account at 1996 quantities was computed by multiplying the 1996 quantities by each year's price

indices for exports, imports

(b)

Invi

The current account

and

in 1

interest payments

.

The other components of the current account were kept at current values,

the 1 996 prices by each year 's quantities. Source:

996 prices was computed by multiplying

Banco Central de Chile

Figure 5 reinforces the mismatch conclusion by reporting increasingly conservative estimates of

the shortage of extemal financial resources

by the non-banking

sector.

Panel

(a) describes the

path of the change in potential financial needs stemming from the decline in temis-of-trade and

capital inflows,

by

and the increase

in spreads. Panel (b) subtracts

the central bank, while panel (c) subtracts

banking

sector.

We

can see from

from about $2 bilhons

to just

from

financial system.

extensively,

show

The

(a) the injection

dechne

above $7

billions.

needs for 1999 ranges

Regardless of the concept used, the mismatch

demand

for resources

from the domestic

difference between panel (b) and (c), as well as the next section

that the latter sector not only did not

accommodate

this increase in

but also exacerbated the financial crunch.

Figure

(s)

5:

The Increase

in Potential Financial

CuTprfiensTi/e

Needs

(b) {a)

minus reserves accumulation

1

1

6.0X

-S?:;-:C

4,000

S

w

^^^^^^^^^^

-2.000

(c) (b)

10

of reserves

in capital inflows to the

this figure that the increase in financial

large, creating a potentially large surge in the

is

(b) the

from

minus flews

to

banking setior

more

demand,

corresponds to the sum of the terms-of-trade effect, the interest rate effect, and the decline in capital

(a)

Both the terms-of-trade and the interest rate effects are measured at 1996 quantities. The decline in capital flows

Notes: Panel

inflows.

corresponds

(a) the net

sector.

To

to the

change

difference of the capital account except reserves with respect to

in

Central Bank reserves. Panel

(c)

subtracts

from panel

its

1996

value.

(b) subtracts

flows

to the

from

banking

Source: Banco Central de Chile

conclude

smooth

demand

the

Figure 6

this section.

illustrates

other dimensions that could have, but did not,

from resident banks. Panel

for resources

"good" news. The former panel shows

that issues

and

(a)

(b) carry the relatively

of new equity and corporate bonds did not

decline very sharply, although they hide the fact that the required retum

rose significantly.

The

latter

panel

illustrates that

while the

flmds to foreign assets during the period, this portfoho

instruments.

some

Panel

(b) the net increase in

However,

this decline

APPs

on these instruments

increased their allocation of

occurred mostly against public

shift

probably translated into a large placement of public bonds on

other market or institution that competes with the private sector, like banks (see the

discussion below). Panel

(c),

on

the other hand, indicates that retained earnings, a significant

source of investment financing to Qiilean firms, declined significantly over the period.^ Finally,

panel (d)

illustrates that

workers did not help accommodating the financial bottleneck

either, as

the labor share rose steadily throughout the period.

Figure

{a)

Change

in

the stock of corporate debt

_

199G

>998

Before the

firm.

in

AFP

holdings as fracfion of

GDP

|_

1999

crises, in 1996, the stock

50%

(b)

m PubBe •

oulsUntHno corporaia dflbl

The difference between

represented around a

11

ChanuB

Other Factors

equity

I

1997

IB New equJN

and new

6:

profits

Financial

a

I

20% of total assets for the median

measure of the flow of retained earnings,

of retained earnings represented

and dividend payments,

a ComMriw B FCTCtiji

of total capital expenditures for the median firm

in 1996.

Retained Earnings

(c)

I

I

M

10%'

=

.1

IH

'

'^

;;;^;,

'

iDFtow/Opcfabon

Notes:

(a)

-.

i_

iSiodt/ToB)

|

Source: Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago and Superintendencia de Valores y Seguros.

New

equity

issuance price, and deflated using CPI. The stock of corporate debt outstanding was also deflated by CPI. The

valued at

December

1998 exchange rate was 432 pesos per dollar, (b) Source: Superintendencia de AFP. The values are expressed as a fraction

of the year 's GDP. (c) The data on retained earnings are from Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago (Santiago Stock Exchange)

and correspond to the stocks of retained earning reported in the balance sheets of all the societies traded in thai exchange.

They exclude investment societies, pension funds, and insurance companies. The flow value was computed as the difference

in the (deflated)

The bottom

stocks at

line

I

and

t-l.

(d)

of this section

Source: Banco Central de Chile.

is clear:

dxiring external

cnmches, firms need substantial additional

financial resources fi-om resident banks.

11.2

The (Supply) Response by Resident Banks

How

did resident banks respond to increased

demand? The

short

answer

is

that they

exacerbated rather than smooth the external shock.

Panel

(a) in

late 90s,

Figure 7 shows that domestic loan growth actually slowed

even as deposits kept growing. This tightening can also be seen

through the sharp

While spreads

makes

12

it

down

rise in the loan-deposit

started to fall

by 1999,

in prices in panel (b),

spread during the early phase of the recent

there

difficult to interpret this decline as

sharply during the

was a strong

substitution

crisis.

toward prime firms

a loosening in credit standards (see below).

that

1

1

Figure?: The Credit Crunch

{a)

(b) Inlerest

Loans and Deposits: Banking Syslem

*»

/'""•'

'

Rate Spreads (Annual %}

"

s

-—^->'

1

""^

-=^

i

a

/^

_.^--^^

s • s $ s s s

i

• 1

1 2

5

S s

8 8 8

HI 11 it H U 1

^ 1

5

Jl

-l.CWC'---DB'OSns

Notes:

(a)

Loans: commercial, consumption, trade, and mortgages. Deposits: sight deposits and time deposits. The values

were expressed in dollars of December 1998 using the average December 1998 exchange rate (472 pesos/dollar), (b) The

30-day interest rates are nominal while the 90-365 are real (to a first order, this distinction should not matter for spreads

calculations ).

Sources: Banco Central, and Superintendencia de Valores y Seguros.

The main

substitutes for loans in banks' portfolios are public debt

alternatives are

toward external

domestic

shown

in Figure 8a, with the clear conclusion that

assets. Interestingly, the central

interest rates

of 1998). Instead, the

and external

was only temporarily

rise in interest rates

succeeded mostly in slowing

down

bank policy of fighting

assets.

banks moved

These

their assets

capital outflows

with high

successful (see the reversal during the last quarter

during the Russian phase of the

the decline in banks' investment in

crisis

seems

to

have

pubhc instmment, and

encouraged substitution away fi-om loans. Banks, rather than smooth the loss of external

funding, exacerbated

illustrates that the

it

by becoming

panel (c) reveals that

much of

of the

the net outflow

credit lines or inflows, but rather

13

part

capital outflows.

banking sector also experienced a large

due

to

capital

was not due

In fact, while panel (b)

outflow during this episode,

to a decline in their international

an outflow toward foreign deposits and

securities.

Figure

(a)

Inveslmanl

in

8: Capital

Outflows by the Banking System

Domestic and External Assets: Banking System

(b)

CZoomwIic

(c)

Notes:

(a)

assets are

Composition

of

—

Net capital rifbws to tjanking sector

Ettemall

Foreign Assets: Banking System

Domestic assets include Central Bank securities with secondary market and intermediated

the

sum of deposits abroad and foreign

securities. Deposits

securities. External

abroad are mostly sight deposits

in

foreign (non-

resident) banks. Foreign securities are mostly foreign bonds.

Sources: Banco Central and Superintendencia de Bancos.

While most

resident banks exhibited this pattern to

had the most pronounced portfoUo

and

(b) in Figure 9,

shift

assets, foreign

degree,

towards foreign

which present the investment

domestic (private) banks, respectively.

some

While

in

all

assets.

it

is

resident foreign banks that

This

is

apparent in panels (a)

domestic and foreign assets by foreign and

banks increased

their positions in foreign

banks' trend was substantially more pronounced. Moreover, domestic banks

"financed" a larger fiaction of their portfoHo

loans. This conclusion

is

ratios for foreign (dashes)

confirmed by panel

shift

(c),

by reducing other investments

rather than

which shows the paths of loans-to-deposit

and domestic (sohd) banks.'"

This figure excludes two banks (BHIF and Banco de Santiago) that changed firom domestic to foreign

ownership during the period. The change

BHIF, and

place in

in July

May

were going

to

in statistical classification

took place in

November 1998

for

Banco

1999 for Banco de Santiago. In the case of Banco de Santiago, the takeover operation took

1999 by Banco Santander (the largest foreign bank

in Chile).

Assuming

that the

two banks

merge, the Chilean banks regulatory agency (Superintendencia de Bancos) ordered Banco de

Santiago to reduce its market presence (the two banks had a joint presence equivalent to 29% of total loans).

The banks finally decided not to merge and therefore their joint market presence has remained unaltered so

far. Most likely the confusion created by the potential participafion limits did not help the severe credit

crunch that Chile was experiencing at the time.

14

-

Figure 9: Comparing Foreign and Domestic

(a)

Investment

in

Domestic and External Assets Foreign Banks

(b)

Bank Behavior

Investment

in

'•.

Domestic and External Assets: Domestic Banks

'"-

.'•

.

'"

/'•'..-:'

-./vv

—

A

/\.

.

^

J\y^^

'

^^s__—x^-.-^-^

SSsS3SSSSSgsS?|SS

4 1 J - 1 1 i s 1 1

Exlomrf -

[

(c)

Loans over Deposits domestk: and foreign banks except BHIF

-

•

DomesBJ

arxJ

Santiago

I

I

=

5

S

I

3

I

=

«

=

I

S

Notes: Domestic banks do not include

I

5

I

Banco

del Estado.

(a), (b)

Domestic assets include Central Bank securities with

secondary market and intermediated securities. External assets are the sum of deposits abroad and foreign securities.

All constant 1998-peso series were converted to dollars using the average exchange rale during December 1998 (472

pesos/dollar),

Loans-to- deposits ratios are normalized to one in

(c)

March

Loans: commercial, consumption, and trade loans, and mortgages. Banco

changed from domestic

these two banks

The question

is

from

arises

to foreign

the Bolsa

whether

1996. Deposit: sight

BHIF and Banco

during the period, were excluded from the sample. The information used

it is

not the nationality but other factors

banks did not experience a

account for additional hedging.

significantly sharper rise in

by a

15

to

separate

(e.g., risk characteristics)

is

explored more thoroughly, the evidence in Figure 10 suggests that this

that foreign

deposits.

de Valores de Santiago (Santiago Stock Exchange).

the banks that determined the differential response. While this

shows

and time

de Santiago, which

rise in net foreign

certainly a

is

tighter capital-adequacy constraint in panel (c).

is

indicated

to

be

not the case. Panel (a)

currency liabiUties that could

When compared with domestic banks, they

non-performing loans as

theme

of

by panel

did not experience a

(b),

or were affected

Figure 10: Risk Characteristics of Foreign and Domestic Banks

(a)

Foreign Currency Assels and

Foreign Banks

Liabilities:

(b)

Non performing

loans as percenlage ot

total loans:

domestic and

foreign tianks

^^

1

rJ

™n

f

rl

,—y~^^~^

/s^^

_^--N

p-.

••

,

1

-•.-•-.....,..--•

1

i 2 s 1

1

1 i 1 3 1

—

r

1

S g s S S

s

1

(c) Capital

ini

i 1

-AMfltt

5

S

ill!?!!

5 5 5 1 1

S

=

•UnbBifiei

adequacy

ratio

,^i^

TTT

"TTTTTTTT

Notes:

(a)

Foreign

assets: foreign loans, deposits

abroad and foreign

abroad and deposits in foreign currency, (b) ROE: ratio of

Domestic private banks do not include Banco del Estado.

securities.

total profits

Foreign

liabilities:

funds borrowed from

over capital and reserves (as a percentage).

Source: Superinlendencia de Bancos e Instituciones Financieras.

Foreign banks usually play

many

useful roles in emerging economies but they

helping to smooth extemal shocks

(at least in the

most recent

crisis). It is

do not seem to be

probably the case that

these banks' credit and risk strategies are being dictated from abroad, and there

is

no

particular

reason to expect them to behave too differently from other foreign investors during these times.

In summary, during 1999 -perhaps the worst fuU year during the crisis

growth by approximately

US$2

banking private sector was about

billions,"

US$2

while the increase in financial needs by the non-

billions as well (see figure 5c).

general equilibrium issues ignored in these simple calculations,

US$4

"

it

is

Although there are

biUions (about

5-6% of GDP)

large,

perhaps around

in that single year.

A number close to two billion dollars is obtained from the difference between the flow of loans

1999 (computed as the change

flow of loans

16

in

1

in the stock

996 (computed

many

probably not too far-fetched

add them up and conclude that the financial crunch was extremely

to

— banks reduced loan

during

of loans between December 1999 and December 1998) and the

in a similar manner).

The Costs

III.

The impact of the

and medium

financial crunch

on the economy

is

correspondingly large, especially on small

size firms.

The Aggregates

111.1

Figure 2 already summarized the first-order impact of the financial mechanism, with a domestic

business cycle that

many times more volatile

is

than

it

would be

if financial

markets were perfect.

This "excess volatility" was particularly pronounced in the recent slowdown, as

panel (a) in Figure

1 1

move

only appear to

together, but the latter adjusts

largely transitory terms-of-trade

unemployment

sharp rise in the

(a} National

shock

is

11

:

more than

by

(dashes) not

implying that the

the former,

not being smoothed over time. Panel (b) illustrates a

rate that has yet to

Figure

95000

is illustrated

The paths of national income (soUd) and domestic demand

.

be undone.

Output, Demand, and Unemployment

Income and Domestic Demand

(b)

Unemployment

rate

.

'~

-

'

-

^

.

-<.^

BOOOO

.•"

1

M

,

^/

L-^-^

,

^

•

^^.^

^^

-^^T"^.^^-^

E

65000

.

60000

.

5O0O0

,

.

-'(OQl-'inQ

5

-

Notes:

(a)

-

3^mDl-'in05

-•

c.tH;

Series are seasonally adjusted

and annualized. Source: Banco Central de

Chile, (b) Source: INE.

Aside fi^om the direct negative impact of the slowdown and any additional uncertainty that

may

have been created by the untimely discussion of a new labor code, the build up in

unemployment and

persistence can be linked to

its

mechanism described above.

exchange

this,

rate

of Figure

financial resources

(see below).

While

line) suffered a

The

larger real

12.

additional aspects

of the financial

I

falls

on

creation, a

crisis

phenomenon

and

a result of

into the recovery, the lack

that is particularly acute in the

do not have job creation numbers, panel

(b)

deeper and more prolonged recession than the

exchange

As

the labor-intensive non-tradable sector, as illustrated

Second, going beyond the

hampers job

and Krishnamurthy (2001a).

17

two

the presence of an external financial constraint the real

needs a larger adjustment for any given decline in terms-of-trade.'^

a big share of the adjustment

in panel (a)

'^

First, in

rate adjustment corresponds to the dual

shows

rest

of

PYMES

that investment (solid

of domestic aggregate

of the financial constraint. See Caballero

demand (dashed

the

line).

This

is

important beyond

its

impact on unemployment, as

slowdown of one of the main engines of productivity growth:

U.S.

is

any

optimistic

indication of the costs associated to this

lower bound for the Chilean costs

productivity loss that amounts to over

slowdown

—

this

it

also hints at

the restmcturing process. If the

in restmcturing

—

possibly a very

mechanism may add a

30% of the employment cost of the recession.

significant

'^

Figure 12: Forced and Depressed Restructuring

(a)

GDP

tratjeable

and norvlradeable

(b) Evohjlion of

t-

.

flomestrc

RCS1

demand

—=FBgl

Series are seasonally adjusted and normalized to one in March 1996. Tradable sector: agriculture, fishing,

and manufacturing. Non-lradable sector: electricity, gas and water, construction, trade, transport and

telecommunications, and other services, (b) Series are seasonally adjusted, and annualized. Source: Banco Central de

Notes:

(a)

mining,

Chile.

As

the external constraint tightens,

must

and hquidity

to

domestic assets that are not part of international hquidity

buy them. Figure 13a shows a

market. Panel (b)

increased

assets.

most

all

lose value sharply in order to offer significant excess returns to the

is

perhaps more interesting, as

it

of this v-pattem

However, while FDI

scarce,

its

is

very useful since

presence during the

See Caballero and Hammour( 1998).

it

investment (FDI)

to the fire sale

provides external resources

crisis also reflects the severe costs

heavy discounts.

will

in the Chilean stock

illustrates that foreign direct

by almost $4.5 bilhon during 1999, and created a bottom

constraint as valuable assets are sold at

18

clear trace

few agents with the

of domestic

when

they are

of the external financial

Figure 13: Fire Sales

Value

(a)

of Chilean stocks (index)

(b)

Foreign Drecl Inveslment (FDI)

"^'

i

llf-lMll-ll

—

I

IGPA

Notes: (a)

is

1997

1996

r^AI

the general stock price index

1999

199B

2000

of the Santiago Stock Exchange. Sources: Bloomberg and Banco Central

de Chile

Gross

(b)

III.2

The

FDI

inflows. Source:

Banco Central de

Chile.

The Asymmetries

real

consequences of the external shocks and the financial amplification mechanism are

differently across firms

of different

sizes.

Large firms are

but can substitute their financial needs domestically.

demand

factors.

The PYMES, on

directly affected

They

the other hand, are

and

to a lesser extent, so are indebted

consumers

external shock

are affected primarily

by

price and

crowded out from domestic

markets and become severely constrained on the financial

-

by the

side.

—

They

felt

financial

are the residual claimants

-

of the financial dimension of the

mechanism described above.

Figure 14

illustrates

some

aspects of this asymmetry, starting with panel (a) that

of the share of "large" loans as an imperfect proxy for resident

Together with panel

(b),

which shows a sharp increase

at a substantial reallocation

I

win argue

19

that

of domestic loans toward

some of this

reallocation is Kkely to

be

shows the path

bank loans going

in the relative size

relatively large firms. In the

socially inefficient.

to large firms.

of large loans,

poUcy

it

hints

section

Figure 14: Flight-to-Quality

(a)

Share of brge toans

in totaJ

loans

(b)

Average size

Strml

I

Notes:

average size corresponds

UF;

larger than 50000

Large loans:

(a)

to the stock

of loans

in

Small loan:

greater than

400UF

of smatl

•

and large loarw

- •Largal

less than

but

10000 UF.

(b)

The

each class divided by the number of debtors.

Source: Superintendencia de Bancos e Instituciones Financieras.

The next

figure looks at cxDntinuing firms fixDm the

relatively large

the largest of

that larger firms fared better as

this period,

FECU

is

more

while

the

by

initial assets)

during the recent slowdown.

medium-sized firms saw

importantly, since the

total

acronym

sheet

of these firms being

that

for

every

shows the path of medium and

size ones. Figure 15

sum of loans

loans declined throughout the

particularly significant in smaller firms (those not in the

balance

all

pubhcly traded companies, one can already see important differences between

them and "medium"

firms' bank-Uabihties (normalized

1999. Perhaps

FECUs.''' Despite

their level

to

firm

in

Chile

is

large firms rose during

the contraction

must have been

FECUs).

Ficha Estadistica Codificada Uniforme, which

public

apparent

of loans fiozen throughout

medium and

crisis,

It is

large

required

to

is

report

the

to

name of the

the

standardized

supervisor

authority

{Superintendencia de Valores y Seguros) on a quarterly basis. Our database contains the information on

those standardized balance sheets for every public firm reporting to the authority between the first quarter

of 1996 and the

20

first

quarter of 2000.

.

Figure 15:

Bank Debt

(a)

Bank

of Publicly Traded Firms

liabilibes of

I

medium and

Mft.ftjm-

-

By

Size

large Hrnis

[jmal

Data source: FECU reported by all listed firms to the Superintendencia de

y Seguros. The sample includes all firms that continuously reported information

between December 1996 and March 2000. Within this sample, the medium (since they are

larger than firms outside the sample) size firms are those with total assets below the median

level of total assets in December 1996. The series correspond to the total stock of bank

Notes:

(a)

Valores

liabilities at all maturities

expressed

in

1996 pesos, divided by the

total level

of assets

in

December 1996). The nominal values were deflated using the CPl. The total level of assets

in December 1996 was VS$788 millions for the group of medium size firms, and

US$59,300 millions for the group of large firms

In summary, despite significant institutional development over the last

economy

is

stUl

two decades,

very vulnerable to external shocks. The main reason for

the Chilean

this vulnerability

appears to be a double-edged financial mechanism, which includes a sharp tightening of Chile's

access to international fmancial markets, and a significant reallocation of resources fi^om the

domestic fmancial system toward larger corporations, pubhc bonds and, most significantly,

foreign assets.

21

Policy Considerations and a Proposal

iV.

The previous

especially

IV. 1

diagnostic points at the occasional tightening of an external financial constraint

when terms-of-trade

— as the trigger for the costly financial mechanism.

General Policy Considerations

If this assessment

a)

deteriorate

~

for a stmctural solution

is correct, it calls

Measures aimed

at

based on two building blocks:

improving Chile's integration to intemational financial markets and

the development of domestic financial markets.

b)

Measures aimed

at

improving the allocation of financial resources during times of

extemal distress and across

While

in practice

states

of nature.

most stmctural poHcies contain elements of both building blocks,

as the guiding principle of the

pohcy discussion below because

already broadly understood and Qiile

dimension through

its

capital

akeady making

is

(a), at least

significant

maikets reform program. That

is,

I

I

focus on (b)

as an objective,

progress

is

along this

focus primarily on the

intemational liquidity management problem raised by the analysis above.'^

Intemational liquidity

management

is

primarily an "insurance" problem with respect to those

(aggregate) shocks that trigger extemal crises.

contingent nature.

large share

trade, the

The

first

step

is

to identify

Of course solutions to this problem must have

a — hopefidly small — set of shocks that capture

a

a

of the triggers to the mechanism described above. In the case of Chile, terms-of-

EMBI+, and weather

index chosen

is

variables, represent a

good

starting point, but the particular

a central aspect of the design that needs to be extensively explored before

it is

implemented.

The second

step is to identify the ex-post transfers (perhaps temporary loans rather than

outright transfers) that are desirable.

level these are simply:

From foreigners to domestic agents.

From less constrained domestic agents to more

i)

v)

At a generic

needs and

let

constiained ones.

level these transfers are clear, but in practice there

availability, raising the information

not already doing as

identifies the policy goals

much

as

is

great heterogeneity in agents'

requirements greatly.

the private sector take over the bulk of the solution,

this sector is

''

At a broad

is

It is

thus highly desirable to

which begs the question of why

is it that

needed. The answer to this question most Ukely

with the highest returns.

See Caballero (1999, 2001) for general policy recommendations for the Chilean economy, including

measures type

(a).

My objective in the current paper is instead to focus and deepen the discussion

subset of those policies, adding an implementation dimension as well.

22

of a

The main

suspects can be grouped into

Among the

a)

supply factors, there are

two

types: supply

at least three

and demand

factors.

prominent ones:

Coordination problems. The absence of a well-defmed benchmark around which the

market can be organized.

b)

These

Limited "insurance" capital.

financial constraint (in the sense that

by

coordination aspects as well,

and

missing

is

that

affect the payoffs

by

respect to aggregate shocks.

The

latter

of

b)

Sovereign problems. Imphcit

c)

Behavioral problems. Over-optimism.

at least three sources

The bulk of

factor (a)

of underinsurance:

depresses effective competition for domestically

crises,

reducing the private (but not the social)

'^

(free) insurance.

view, domestic financial underdevelopment

demand

and

is

still

to supply factor (b) as

a problem in Qiile, which gives

it

reduces the size of the effective

the solution to this problem should be pursued through financial market

reforms. In the meantime, however, an adequate use of monetary and reserves

poUcy may remedy some of the underinsurance impUcations of this

the general features of this

in Caballero

Similarly,

demand

in the next section.

deficiency. I briefly discuss

A more extensive discussion can be found

The

is

factor (c)

seems to be a pervasive human phenomenon (see

whose macroeconomic impUcations can

latter

problem, which

and neither

poUcy

management

and Krishnamurthy (2001 c).

Shiller 1999),

policy.

is

must be done with great care not

for

example

also be partly remedied with the above

to generate a sizeable

demand-(b) type

otherwise not likely to be present in any significant amount in the case of Chile

supply-(c).

This leaves us with supply-(a) as the main focus of the poUcy proposal, which

extensively in section TV. 3.

" See, e.g., Tirole (2000).

" See Caballero and Krishnamvirthy (200

23

parties,

of these contracts.'^

valuation of international liquidity during these times.

market.

"

This leads to a private undervaluation of insurance with

available external liquidity at times

my

due to a

be credibly pledged

A closely related problem, but with

the "insurers.

one should consider

Financial underdevelopment.

relevance to

assets that can

an insufficient number of participants in the market

collateral risk faced

Among the demand problems,

In

to structural shortages or

is

(dual-agency) problems. While contracts are signed by private

Sovereign

government actions

a)

is

the "insurer," rather than actual funds during crises).

raises the hquidity

c)

may be due

what

1

a, b).

I

discuss

IV.2

Monetary Policy as a Solution

to the

of an external

Figure 16 provides a stylized characterization

described up to now.

Underinsurance Problem

The main problem during an emerging market

the presence of a "vertical" external constraint. That

margin,

it

becomes very

financial markets at

of the

crises

any

difficult for

As

price.

is,

crisis is

to gain

any access to

this, international liquidity

domestic competition for these resources bid up the "doUaf' -cost of

by prime

international interest rate faced

crunch

is

a sharp

fall in

when,

at

the

international

becomes scarce and

capital,

(international) Chilean assets,

have

1

well captured by

external crises are times

most domestic agents

a result of

sort that

/*.

above the

f^,

The

dual of this

investment.

Figure 16: External Crisis

t

7*

I^

It is

important to clarify a few aspects of this perspective of

some confusion

a)

Particularly in the case

measure of the

b)

It

of Chile, the

rise in the

rise in

vertical constraint to

scarcity is

seldom the

perceive that there

is

case.

But

it is

literally

enough

Fleming type

;

rather,

it

not a

represents

runs out of intemational liquidity for the

that

some

crisis

may

the intemational liquidity rather than lend

that follows

i^- /*, is

seldom

new

it

lie

ahead, for

domestically,

positive.

vertical but '"diagonal." In that case the

must be blended with

analysis, but the interesting

total

prime firms, banks, and the government

a significant chance that a severe external

in practice the constraint is

of the analysis

f

is

bind for small and less than prime firms. In fact in Chile

to decide to hoard

Of course,

logic

to have caused

may tighten the vertical constraint.

even when the current domestic spread,

c)

seem

sovereign (or prime firms') spread

domestic (shadow or observed) rate

needs not be the case that the country

them

crisis that

in the past:

the rise in /*, which in turn

24

Investment

insight is

that

still

of the standard Mundell-

that

which

related to the non-

,

flat

aspect of the supply of funds.

Ex-post-Optimal Monetary and reserves policy during

crisis

Before discussing optimal policy fijom an insurance perspective,

bank faces during an external

incentives that a central

The main

shortage experienced

by

the country

is

it

is

worth highhghting the

crisis.

one of

international Uquidity (or "collateral,"

broadly understood). Thus, an injection of international reserves into the market

powerful

tool:

stabilizes the

To

see the

there

is

directly relaxes the "vertical" constraint

it

exchange

latter,

credit constraint.

crisis international arbitrage

Domestic

and dollar instruments backed by domestic

arbitrage,

collateral

f'

(1)

where f denotes de peso

rate for next period. In

when

this

a very

it

=f

expectation

is

I

take the

affected

on the other hand, must

hold. Peso

(risk

is:

+(e-Ee).

exchange

interest rate, e the current

what follows,

does not hold since

must yield the same expected return

aversion aside). Thus the domestic arbitrage condition

arise

is

in Figure 16, and

rate.

note that during an external

an extemal

on investment

rate,

by poUcy

and Ee the expected

interest

although interesting interactions

latter as given,

as well (see

CabaUero and Krishnamurthy

2001c).

Rearranging (1) yields and expression for the exchange

e~Ee=

(2)

which shows

that as

given peso interest

The

effectiveness

f

facilitates

H',

of an expansionary monetary pohcy. The reason for

crisis is the

domestic loans and hence the role of

lower peso

this is that

interest rates raise investment

Part of the reason for the "diagonal" shape in practice

is

f

in the investment function in

demand)

constraint.

As

but, to a first order,

25

it

a result, an expansionary

that the currency depreciates as

I

rises. If

exports are an important dimension of the country's intemational liquidity, then a depreciation increases

intemational collateral.

rate

lack of intemational not domestic hquidity.

does not relax the binding intemational financial

'*

and protecting the exchange

injections in boosting investment

main problem during an extemal

Figure 16 (given

f

rate.

of reserves'

Domestic hquidity

-

with the reserves' injection, the exchange rate appreciates for any

falls

contrasts sharply with the impact

the

f'

rate:

monetary policy

impact

is

equation

not effective in boosting real investment in equilibrium. Instead,

is

(2), the latter

offset the reduction in

f

In conclusion, a central

have much

means

that the

real benefits

exchange

rate depreciates sharply, as

(the standard channel) but also absorb the rise in

bank

that has

may have on

the exchange rate

it,

an inflation target and

will rather tighten

during the

crisis

if the central

and can lead

tighten during a

bank could commit ex-ante

The answer

crisis.

is

no.

is

of the

crisis

during the

but

is

it

boom

not ex-ante.

years,

It

to a

The reason

concemed with

exchange

to a sharp

the impact that

rate depreciation.

monetary policy, would

it

for this is that the primitive

crisis

how much

sectoral

international

allocation

still

choose to

problem

is

the

The amount of

may be exogenous

at the

time

borrowing occurred

on the maturity stmcture and denomination of

contingent credit lines contracted, on the

By

crisis

an external

depends on

f'.

must not only

t'.

private sector's underinsurance with respect to aggregate external shocks.

international Uquidity that the country has during

it

monetary policy. Doing otherwise does not

Ex-ante-Optimal Monetary and reserves policy during

But

and hence

to raise domestic competition for the limited international liquidity,

main

its

that debt,

on the

of investment, and so on.

Underinsurance means that these decisions did not fully internalize the social cost of sacrificing a

unit

of international

hquidity. Figure 17 captures this

Figure 16. The gap A-

i'

captures the undervaluation problem. In other words, had the private

sector expected value of a unit

more

gap by adding a social valuation curve to

of hquidity being

A

as

opposed

to

i^

right.

Figure 17: Underinsurance

Social

,•*

26

,

intemational Uquidity and the vertical constraint during the crisis

10^^)

they would have hoarded

would have

shifted to the

Thus, while an expansionary monetary pobcy during a

anticipation

make

If private agents anticipate such policy, they will expect a higher

is.

ex-ante decision

What

in line with those of the social planner.

one of incentives

is

an external

scarcity during

i^

more

of monetary poUcy

role

unable to boost investment,

crisis is

and hence will

main

In this context, the

one of Uquidity provision, for the main

rather than

crisis is international rather

f'

its

than domestic hquidity.

about intemational reserves' injections? They are

optimal ex- ante, however the

stUl

they bring about have a perverse incentive effect that also needs to be offset

fall

by

in

the

expansionary monetary policy.

Before concluding

a)

There

this section, I shall

mention two caveats:

a related but distinct type of monetary policy ineffectiveness that arises dviring

is

the recovery phase of an external crunch.

WhUe

intemational Uquidity

the binding constraint in this phase, the lack of domestic collateral

during the intemational crunch

lost

injects resources into the

binding constraint

b)

Finally,

the

is

commitment

is.

An

Ee

much

this is the case

does not reach the

as given throughout. If this

PYMES

this

—

case

since the

not warranted, in the sense that

is

policies during the extemal crunch, then

an available incentive mechanism. Having

resort to

it

and

to a post-crisis inflation target is not sufficiently credible

compromised by

PYMES

by the

expansionary monetary policy in

banking system, but

longer be

not the availability of loanable funds.

have taken

I

—

may no

is

seriously

may not be

may have to

monetary poUcy

lost the latter, the authorities

costher incentive mechanisms such as capital controls.

I

do not beheve

of Chile today.

IV.3 Creating a market: Issuing a bencfimarl<-contingent-instrument

As

I

mentioned before,

I

suspect another key aspect behind underinsurance

coordination problem. While there are

many ways

to hoard intemational liquidity

they tend to be cumbersome and costly for most, especially

insurance.

The

basic proposal here

is

when

issuer, this

one

in section IV.l. Ideally,

bond should be

free

the goal

extremely simple: The Central

the IFIs should issue a financial instrument -a "bond" for

identified in step

of other

risks.

now—

Bank

is

desired insurance

to create the market.

With

may be

It is

its

The

issue should

achieved directly by

own

and hedge,

to obtain long

or, preferably,

term

one of

and hence the role played by a reputable

be

significant

bond,

this

the basic contingency well priced,

for the private sector to engineer

simply a

contingent on the shocks

the participation of intemational institutional investors and hence generate

some of the

is

it

its

its

first

enough to

attract

Uquidity.

WhUe

main purpose

is

simply

should be substantiaUy simpler

contingent instruments.

important to realize that the contingency generated via this

mechanism addresses only

the

expected differential impact of the aggregate shocks contained in the index. Individual agents

27

hedging through

will generate heterogeneity in their effective

their net positions rather than

through a change in the specific contingency." Other, more idiosyncratic underinsurance

problems are also welfare reducing but are

the concern in this paper

While

connected with aggregate stabihzation, which

is

of how responsive should be the contingency to the underlying

in principle the question

insurance factors or indices

is

considerations suggest otherwise.

bond contingency very

be able to develop the

irrelevant since the private sector should

derivative markets that can generate

the

less

.^^

any slope they

With the

latter

"steep," so as to

required to generate an appropriate

may

need, financial constraints and Uquidity

considerations in mind,

it is

desirable to

make

minimize the leverage and derivative instruments

amount of insurance

for large crises.

The

counterpart will

probably be a very limited insurance of small and intermediate shocks, which should be fine

since these shocks seldom trigger the financial amplification

How much

many

mechanism highhghted

insurance does the country need? This question

is

in this paper.

not easy to answer as

it

involves

general equilibrium considerations, but a very conservative answer for a full-insurance

upper bound should not be very

trigger the

from the

partial

equihbrium answer. Crises deep enough to

complex scenarios experienced by Chile recently are probably once

and according to our estimates earUer on the

events,

dollars a year, lasting for at

of the

far

damage

created

by the lack of

is

in a

decade

about 5 biUion

most

likely the result

insurance, rather than the direct effect

of the external

most two years (recessions longer than

But the required insurance

shocks).

of resources

is

shortfall

this are

only a fiaction of this shortfall since