Document 11157811

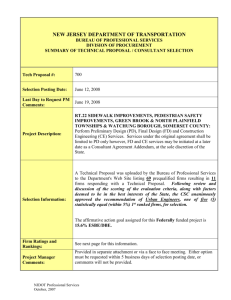

advertisement