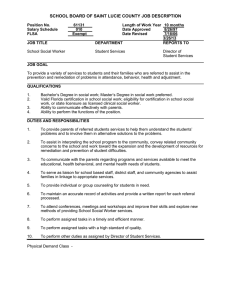

Document 11157798

advertisement

•k

[

\

LIBRARIES

•

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/certificationoftOOacem

oB/m^^

HB31

.M415

'''^

IV

/

working paper

department

of

economics

Certification

Of Training And

Training Outcomes

Daron Acemoglu

Jorn-Steffen Pischke

No. 99-28

October 1999

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass. 02139

WORKING PAPER

DEPARTMENT

OF ECONOMICS

Certification

Of Training And

Training Outcomes

Daron Acemoglu

Jorn-Steffen Pischke

No. 99-28

October 1999

MASSACHUSEHS

INSTITUTE OF

TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASS. 02142

MASSACHUSETTS iWSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

NOV

2 G 1999

LIBRARIES

Certification of Training

and Training Outcomes

Daron Acemoglu and Jorn-Steffen Pischke

MIT

July 1999

Abstract

External certification of workplace

is

widespread

in

many

countries.

skills

This

may

obtained through on-the-job training

indicate that training

is

financed by

workers, and certification serves to assure the quality of the training offered by the

is financed by firms, esGermany. We show in this paper that external certification of training

may also be necessary for an equilibrium with firm-sponsored training. Firm financing of training is only possible if firms have monopsony power over the workers

after training. If the training firm can extract too much of the employment rents,

firm.

However, other evidence shows that general training

pecially in

however, workers

ing.

may

not have sufficient incentives to put forth effort during train-

Certification increases the value training to the outside market,

workers, making firm-sponsored training possible.

and hence to

Introduction

1

Standard theory of human capital as developed by Becker maintains that workers should

pay

for investments in general skills.

by independent bodies,

especially

It

makes sense that such

when the

skills

are often certified

skills

are provided by firms at the workplace.

However, various pieces of evidence suggest that in a variety of circumstances firms rather

than workers pay

for investments in the general training of their

example. Bishop, 1997, Acemoglu and Pischke, 1999a).

that this

may be because other employers do not

Many

due to external

if

may be

certification of skills, there

for

observe whether an employee has received

become more

training programs

(see,

economists have suggested

training with his current employer (Katz and Ziderman, 1990,

According to this view,

employees

less

Chang and Wang,

easily identifiable, for

1996).

example

investment in training by firms.

In discussing proposals for occupational certification in the U.S., Heckman, Roselius, and

Smith (1994),

for

example, raised this

and argued that increased

issue,

certification

would

discourage training.

In this

light,

Germany's training system

is difficult

to understand.

Germany has an

extensive apprenticeship system which most non-college-bound youths complete before

becoming

full-time workers.

Many

studies have

documented that employers pay a

icant part of the financial costs of these training programs (see for

presented in Acemoglu and Pischke, 1998).

exams given by the chambers

of the training period,

and receive

received

The presence

certificates

of certificates that

by a worker observable to

example the evidence

However, apprenticeships are highly regu-

lated; apprentices take

skilled jobs.

of

commerce and

crafts at the

which play an important

make the amount and

end

role in access to

quality of the training

potential employers suggests that

about the quality of training that underlies

signif-

it is

not uncertainty

firms' incentives to invest in general skills in

Germany.

In Acemoglu and Pischke (1998), we developed an alternative theory of firm-sponsored

training based

on an asymmetry of information between current and potential employers

regarding the ability of young workers.

Valuable information about the abilities and

aptitudes of young workers will be revealed diiring the early years of their career.

Much

of this information will be directly observed by the current employer, but not necessarily

by other

skills

firms.

This informational monopsony

of their employees.

We

program, which they often

induce firms to invest in the general

argued that this theory accounts

the apprenticeship programs in Germany.

puzzling for this theory as well.

will

for the prevalence of

Nevertheless, certification of training skills

is

Why do firms operate within the regulated apprenticeship

criticize as rigid

and outdated, rather than developing

their

own

training programs without certification?^

We

In this paper, we attempt to answer this question.

tion of training in a labor market where

example

tion of

in the

form of

We

skills.

effort, is

discuss the role of certifica-

some investment by the workers themselves,

necessary during training for the successful accumula-

show that contrary to conventional wisdom,

certification

be necessary to encourage firm-sponsored training. The institutions that

ticeship skills therefore

may

actually

certify appren-

emerge as an integral part of the German training system, and

would not increase firm-sponsored

their removal

for

training, but likely

undermine the whole

system.^

The underlying

intuition for our results

employees because they have

sufficient

is

simple. Firms invest in the training of their

monopsony power, which makes them,

While labor market imperfections,

part, the residual claimant for the returns to training.

and

in particular

at least in

asymmetric information, increase the monopsony power of firms and

encourages firms to invest in training, they also reduce the workers' incentives to invest

in their skills, as

the worker

is

most of the returns

will

be appropriated by the

effort,

commit to reward workers

effort.

But

the problem woiild be solved.

diligence that workers exert in training programs

firms could

If

like

is

effort activities,

hard to monitor.

is

and

the

Alternatively,

if

conditional on their effort, the right incentives

often not possible in equilibrium either. This

in the labor

firms could observe

most

could be given to workers. Since the efibrt choice of the worker

this

by

If effort

necessary to complete the training, the labor market arrangements have

to give sufficient incentives to workers to exert this

monitor such

firm.

is

not observed, however,

means that asymmetric information

market might undermine the existence of training programs by not giving

enough incentives to workers. In

this setting, certification arises as

a method of ensuring

that workers receive more of the return to their general training. Certification therefore

helps to balance the power between workers and firms evenly, encouraging workers to

exert effort. In fact, in our simple model, firm-sponsored training arises as an equilibrium

with

certification,

We

but without certification training

next outline the basic environment.

in the absence of certification.

firms caimot

We

is

In section

never an equilibrium.

3,

we

characterize the equilibrium

simplify the analysis in this section

commit to future wages, and show that

by assuming that

in the absence of certification, there

^Although the German firms are currently not allowed to design their training programs, this is a

though they

could do so.

^Burtless (1994) makes an informal argument that more certification would encourage workers to

obtain more training but does not clearly articulate the reasons why there is too little training without

relatively recent development. In the past, they chose not to develop such programs, even

certification.

be no training in equilibrium. In section 4 of the paper, we solve

will

for the equilibrium

with certification, and show that there now exists an equilibrium in which firms invest in

the

skills of their

we

5,

workers, and workers exert effort diiring the training period.

relax the assumption of no

commitment

to future wages,

In section

and show that even

presence of such commitment, certification facilitates training. In section

6,

we

in the

discuss

further extensions of our results.

The Environment

2

The economy

are low ability,

At

i

and

=

0,

number

consists of a large

and the remaining

—p

1

no one knows a worker's

A

firms.

fraction are high ability.

fraction

There are two periods.

but other firms do not. This asymmetry of

ability,

information between the current employer and potential employers

monopsony power that

will lead to

Workers are not productive

output of a worker in period

where

/i

=

1 for

i

at

=

i

=

=

1 is

=

low ability workers, and

/i

worker.

upon.

o;

—

1

The effort

The

>

The

is

e

=

choice of the worker

analysis

If

is

unaffected

cost of training

is

or

=

>

1 for

high ability workers, r denotes

a worker receives no training, r

1

effort to benefit

where

e

=

1

is

=

0,

otherwise

We

denote

has a disutility cost of c for the

and cannot be contracted

and low

ability workers,

no discounting.

7 per worker and

t

=

from training.

costs differ across high

There

workers are unable to bear this cost at

77

his private information

is

if effort

the return to training.

a^^h

some

also needs to exert

the effort choice of the worker by

the source of the

but they can be trained during this period. The

0,

y

The worker

1.

is

firm-sponsored training in our economy.

whether the worker was offered training.

T

p of workers

but at the end of the period a worker himself

ability,

employer learn this

his current

and

of workers

0,

is

incurred by the firm.

so

all

We

assrune that

training has to be firm-sponsored.^

Moreover, since firms cannot distinguish between high and low ability workers at the

begirming of

i

—

0,

training has to be offered to

possible because at this point workers do not

at the beginning of

A

fraction

i

=

A of workers

1,

all

know

workers.

their

Self-selection

own

ability either.

workers decide whether to stay with the

will quit irrespective of the

is

initial

also not

Finally,

firm or not.

wages in the outside market. The

^See Acemoglu and Pischke (1999a, b) for a discussion of possible reasons for

unable to buy training from their employers.

why workers may be

remaining fraction

wage

offered

1

—A

of workers will stay in their current job

by the current firm and

;;

is

if

training depending

on the

rangements. In the

first,

fore, outside firms will

off.^

no

is

w

abilities

is

the

and whether

They may observe whether the workers

institutional arrangements.

there

where

v,

the wage offered by the outside market.^

Firms in the second hand labor market never observe workers'

they have quit or have been laid

w>

We

certification of skills

distinguish between

receive

two

ar-

by independent bodies. There-

not observe whether a worker has successfully completed a training

program. The second institutional setup, which

is

similar to the

system, involves an outside body that runs examinations and

German

certifies

apprenticeship

the successful com-

pletion of training programs.

The

outside labor market

make

their information, firms

beginning of time

^

=

is

W to ensure zero

wage

due to

is

competitive, so wages will be such that conditional on

zero

profits.*^

We

also

competitive, so firms

profits. Intuitively, if

assume that the labor market

may have

the firm will

ex post monopsony power, then competition at

its

this profit in the

form of upfront wages,

to

pay a

make

t

=

first

at the

period training

positive profits at

will force it to

t

=

1

pay out

W.

Equilibrium Without Certification

3

We

start

there

by showing that

no

is

in the absence of certification, there will

certification, all

a unique wage

To prove

v. It is

this,

workers in the outside labor market are

be no training. As

alike,

so there will be

straightforward to see that workers will not exert training effort.

suppose that firms offered training and workers exerted

effort.

In this

case the outside wage would be

,^

where

qi is

+ (l-p)g.r?

^

pqi + {l-p)qh

Pg/

(1)

the probability that a low ability worker separates from the current firm (due

to a quit or layoff)

and

qn

is

the probability that a high ability worker separates from

the firm. This equation ensures that firms in the outside market, which do not observe

worker ability or training, make zero profits in expectation. Since worker training

observed, a worker

W+v

(first

*This

^A

is

who

is

not

deviates and chooses not to exert effort will get utility equal to

period wage,

W, and

outside wage, v). Also notice that the

maximum wage

the formulation of the asymmetric information model used in Acemoglu and Pischke (1999b).

is vacuous in this simple model anyway, since the firm can always set wages so as

distinction that

to induce

all

^Formally,

(1998).

low ability workers to

we

quit.

are looking for a Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium of this game. See

Acemoglu and Pischke

.

that the current firm will pay in the second period

time;

if

the firm paid a higher wage,

necessarily

make

W+v—

most

is

w =

the outside wage at the

v,

would not retain any more workers, so would

This implies that the return to a worker exerting

less profits.

which

c,

it

is

strictly less

than the

utility

from not exerting any

effort is at

effort,

W+

v.

not exert

effort,

and so there

unable to reward workers for exerting

effort;

outside firms cannot

This implies that without certification workers

will

be

will

no training.

Intuitively, firms are

distinguish trained and untrained workers, so

all

workers will earn the same wage in the

This in turn means that the training firm will also pay a single wage

outside market.

and untrained workers.

to both trained

It

could promise ex-ante to pay a higher wage

Absent a possibility

to trained workers, but such a promise would not be credible.

committing to

this higher wage, the firm

We

reneging on this promise.

would always benefit

assume such a commitment

Also notice that there

to this issue in section 5 below.

in the

for

second period from

not possible here but retiirn

is

no

is

role for training firms to

engage in certification of training themselves. Since the firm benefits from paying a lower

wage,

it

has an incentive not to certify any workers as trained.

Equilibrium

rf)

—

now

is

Employers at

straightforward to characterize.

V to their high ability employees, and at most

w{h

=

1)

=

i

=

1 offer

all

low ability workers

will

=

to low ability workers.^

1

1,

and

where the

last

Since a fraction A of high ability workers quit, outside wages v will be greater than

therefore

w{h

indeed quit. Outside wages are

p+(l-p)A

Firms make second period

equality defines

11,

profits in period

4

which

=

^

0,

is

profits of IIo

=

(1

—

A) (1

—p)

(77

—

u)

=

11

a term that will reoccur throughout the paper. To ensure zero

firms will pay upfront wages VT

=

11.

Equilibrium with Certification

Now

consider the

same economy with an outside body

training. In this case outside firms

do not observe

certifying successful completion of

ability,

but they observe whether the

worker has successfully completed training. Notice that certification implies that the firm

has offered training and the worker has exerted

wages now, one

^When

t;„

offering a

strategy as a "layoff"

for

effort.

There

will

be two different outside

workers without certified training, the other

wage w{h

=

1)

=

1 firms realize

that workers will quit.

vt for

We

a worker with a

therefore refer to this

certificate of training.

With the same reasoning

+ {1 - p)qiv ^

pqj + (1 - p)ql

+ {l-p)qhV

pqf + (1 - p)ql

pq?

pqj

where g"

is

the probability that a low ability worker

because the firm did not

The

the firm.

Now

we have

as above

who

does not have training (either

because he did not exert

ofTer it or

.„.

effort)

has separated from

other g's are defined similarly.

consider an allocation (a candidate equilibrium) in which firms offer training to

all

their workers,

to

all

and

who

workers

workers exert

all

effort. Specifically,

the firm offers a wage of Wt

are high ability and have exerted effort, and lays off

all

= Vt

other workers.

In this case, the outside wage for workers with the certificate (who are necessarily trained)

will

be

Vt

The wages

in the

no

ability

certification case.

1.

the outside wage

firm

may want

A

(3)

-,

who have

for workers

produces

= P+{1-p)Xt]

r-r(^-

worker

not exerted any effort are going to be the

who has

same

as

not exerted effort and turns out to be low

Since some high ability workers will be in the outside market again,

is ?;„

>

1,

so the initial firm will not retain any low ability workers.

to keep high ability workers without training, by offering

if

the productivity of these workers

rj

>

77

is

greater than

Vn will always be the case, so the outside wage

?;„.

It is

them Wn

The

=

Vn,

straightforward to see that

is

p+(l-p)A

and a firm keeps some

of high

and low

of the high ability workers

ability

who have not exerted effort. The fraction

workers in the outside market are

and do not depend on behavior because workers make

their type.

This implies

Vt

still

the population fractions

their effort decision before

knowing

= aVn.

Next, we can determine whether workers prefer to exert effort during training.

will

do so

if Vt

>

Vn

+

c.

Substituting from (3) and

(4),

we

They

find that this inequality

is

equivalent to

that

is,

the rettirn to training should be sufficiently high, especially as compared to the

cost of effort,

c.

We assume this condition holds in the rest of the analysis. The presence

6

of training certificates

to their

hence

skills,

now

Is it

now

ensures that the outside market rewards the workers according

effort,

ensuring the correct incentives.

Consider the profits of a firm that

also profitable for firms to offer training?

offers training in this equilibrium,

=

lit

where

(1

-

was defined above.

11

-

p) {arj

In contrast,

if it

-

vt)

- 7 = an -

chooses not to train,

employees

will prefer to invest in the training of their

{a

a and

and

so,

77

are sufficiently large

and 7

is

As

before,

The main

—

> n„

and

be

Wt

=

all

—

therefore that, as long as conditions (5)

is

an equilibrium with training when the training

satisfied,

certification.

7.

and

(6)

results are externally

Given conditions

To

and

(6),

see this,

add

(5)

obtain

(a-l)(^;

+ n) >

^Wt + avt- c

where we have exploited the

hand

if

an equilibrium with firm-sponsored

will exist

but no training in the absence of

(6) to

or

- l)n > 7

welfare will be higher in the equilibrium with certification and training.

(5)

are

(6)

Q wages adjust to ensure zero profits, hence

result of this section

hold, there will be

certified,

t

if Ilf

sufficiently small, this condition will

with certification of training, there

training.

its profits

> 7

(a-l)(l-A)(l-p)(7y-i;„)

If

7,

= (i-A)(i-p)(77-?g = n

n„

Firms

A) (1

fact that

side of the second line of (7)

while the right hand side

is

is

>

W = U,

7

+c

(7)

W+v

Wt

=

all

—

7,

and a

>

1.

left

the utility of a worker in a training equilibrium,

the utility in a no training equilibrium. Since firms

profits, (7) establishes that welfare in

The

the training equilibrium

is

greater.

make

zero

Certification

is

therefore welfare enhancing.

Training Avith

5

Our

at

analysis above

time

i

=

1,

assrmiption for

Wage Commitments

was simplified by the assumption that firms

ruling out

many

commitments to wages.

firms, for large

Although

German companies,

it

set the post-training

this

may be a

wages

reasonable

might be more plausible to

assume that they can

vise their

reputation to commit to a wage path.^

It is

important to

investigate the role of this assumption since in the presence of such commitments, training

may be an equihbrium

even without

exploited the fact that the

maximum wage

worker had nothing to gain by exerting

without exerting

The

t

=

1,

Intuitively,

certification.

our analysis in section 3

the firm will pay at

effort as

t

=

1

is

w =

v,

so the

he could get the outside wage v even

effort.

alternative

is

a situation in which the firm commits to a higher wage in period

say Wc, and encourages workers to exert

however. Because

we do not have

effort.

worker

certification,

There

effort is

is

an important constraint,

not verifiable, and therefore

contracts cannot be contingent on a worker's effort choice. This implies that Wc has to

be high enough so that the expectation of getting

exert effort.

be

laid off

Only high

and receive

effort choice, so

v.

this higher

ability workers will receive

wage encourages workers to

Wc while low

Workers do not know their

ability

ability

workers will

when they have

to

make

they will base their decision on the expected gain from exerting

still

their

effort.

Since low ability workers will be laid off and a fraction A of high ability workers will quit

voluntarily, the

maximum

which needs to be

expected gain from exerting

at least as great as

lay off high ability workers,

run interest of the

who have

—

p) (1

—

A) {wc

—

v),

assume that the firm can commit to

effort,

even when

it is

not in the short

firm.^

all

workers exert

for retained

effort,

Vt

Therefore,

also

not exerted

Suppose the firm commits to a wage

This implies that

We will

c.

effort is (1

=

workers sufficient to encourage

effort.

hence

p+{l-p)Xr]

r-rCt

p + {l-p)X

;

we need

'"'=(l-p)(l-A)+'"

Without

certification, the firm will only follow the training strategy if profits

Het

=

(1

-

A) (1

- p)

{arj

-

w,)

from training

-j

we could imagine a repeated game similar to our static economy where firms are

but workers live only two periods. If workers can observe the past wage offers of firms,

there could exist a self-sustaining equilibrium where firms would be punished if they renege on their wage

promises. To keep the exposition simple, we do not discuss this more complicated model in this paper.

"In a repeated game framework, if the firm were to retain a worker who has not exerted effort, then all

workers in the future would prefer not to exert effort. Therefore, retaining such workers is incompatible

with a wage commitment strategy.

*More

formally,

infinitely lived,

are larger than the profits

of

commitment but no

<

Uct

IT

effort.

it is

unprofitable for firms to provide training

This condition together with

7< (aWhen

(5)

and

both

(8) are

a set of parameter values, defined by

certification, there exists

n, which ensures that

worker

from not training workers. Thus, even with the possibility

side certification.^*^ Thus,

and encourage

(6) implies

l)n <

satisfied, firms will

c

+ 7.

(8)

provide training only

when

there

wage commitments do not necessarily ensure equilibrium

sponsored training without

certification,

and

certification institutions

may

still

out-

is

firm-

be neces-

sary for high investments in training.

Concluding Remetrks

6

We

have kept the model above deliberately simple to clearly

may be

of our analysis: external certification of training

illustrate the

necessary to provide

incentives for workers to contribute their part to training investments

invest in worker training.

the qualitative results.

Many

choose to exert

siifficient

and ensure that firms

of the assumptions are very special but not essential to

It is useful at this

point to discuss briefly a few of the key ones.

The assumption that workers do not know their type ex-ante,

ble in this strict form, is not crucial. Our basic results still hold

their type ex-ante.

main point

while relatively implausiif

workers perfectly knew

In the case with commitment, however, low ability workers will not

effort

anymore, since they do not get a payoff from

More important,

it.

the firm will be able to induce high ability workers to exert effort with a lower wage com-

mitment. The range of parameters where wage commitments can ensure firm-sponsored

training will therefore be larger.

In the case of Germany, however, where workers enter

apprenticeships at a relatively young age, like 15 or 16,

good knowledge about

all

their

We have also assrmied that

who have

and

own

may be

unlikely that they have very

aptitudes and comparative advantages.

certification allows perfect discrimination

exerted effort during training and those

ability

it is

who have

not.

between workers

In practice, effort

more able workers may be able

substitutes in examinations, so that

to obtain the training certificate with less effort than low ability workers.

^°In fact, the condition for

commitment

to ensm'e training

is

This makes

more stringent than the one given

in

the text. Equihbrium commitment requires the discounted present value of a profit stream, Ilct/r, to be

greater than the alternative, where r is the discount rate. The firm will receive a larger profit now from

reneging on the promised wage w^ to trained workers now.

premium, but

also receive only profits 11

from then on.

This condition boils down to the one in the text when r

It will

pay them

Vt instead,

saving the wage

This means commitment requires

—

>

0.

Ilct

>

11

-I-

re.

putting in no effort more attractive for workers in the certification case, and tlierefore

more

leads to a

In

more

t

=

stringent condition than (5).

Acemoglu and

interesting

1 is

Pisclike (1998),

is

not completely exogenous.

Instead,

and

i.e.

a probability distribution function.

are possible.

One

equilibrium

lots of training, while

wage and

little

may be

we model the

for

a fraction

We

1

— F{w —

show that

It is

workers quits, where

in this setup multiple equilibria

characterized by few quits, low outside wages,

similarly possible to obtain multiple equilibria in the

an economy without such

and no training may not necessarily lead to a high training

initial

turnover rate of the economy

in this particular economy, even

highlights that certification

in

v) of

an economy

like

on

another equilibrium exhibits a high quit rate, a high outside

or no training.

example, the

model becomes

quit decision as depending

certification case. This implies that introducing certification in

credentials

selection

when the decision of workers to quit voluntarily at the beginning of period

the relative inside and outside wages,

F

we show that the adverse

is

though

it

is

equilibriiun.

too high, training

may

If,

not arise

could be sustained as an equilibrium.

This

only one institutional feature which helps support training

Germany.

10

References

[1]

Acemoglu, Daron and Jorn-Steffen Pischke (1998)

"Why do

firms train?

Theory and

evidence," Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, 79-119.

[2]

Acemoglu, Daron and Jorn-StefFen Pischke (1999a) "Beyond Becker: Training

perfect labor markets,"

[3]

Economic Journal Features

109,

in im-

February 1999, F112-F142.

Acemoglu, Daron and Jorn-Steffen Pischke (1999b) "The Structure of Wages an

In-

vestment in General Training" Journal of Political Economy, 107, June 1999, 539-572.

[4]

Burtless,

Gary (1994) "Meeting the

skill

demands

of the

new economy,"

Solomon and Alec R. Levenson Labor markets, employment

policy,

in:

Lewis C.

and job

creation.

Boulder, Co: Westview Press, 59-81.

[5]

Bishop, John H. (1996)

of the literature," in

"What we know about employer-provided

Solomon Polachek

(ed.)

training: a review

Research in Labor Economics,

vol. 16,

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 19-87.

[6]

Chang, Chun and Yijiang

Wang

The Pigovian

information:

(1996)

"Human

capital investment

under asymmetric

conjecture revisited," Journal of Labor Economics 14, 505-

519.

[7]

Heckman, James

and training

consensus"'

policy,

[8]

J.,

policy:

in:

and job

Rebecca

A

L. Roselius,

and

Jeffrey A.

Smith (1994) "U.S. education

re-evaluation of the underlying assumptions behind the 'new

Lewis C. Solomon and Alec R. Levenson Labor markets, employment

creation. Boulder, Co:

Westview Press, 83-121.

Katz, Eliakim and Adrian Ziderman (1990) "Investment in general training:

of information and labour mobility,"

Economic Journal

11

100, 1147-1158.

The

role

DEC

^nnnDate

Due

Lib-26-67

,MJT

LIBRARIES

3 9080 01917 6285

ip."^'

It:

t

It

I

6

r't"

7

i-fl

8

9

10

;

11

ll|l|l|l

l|l|M

_JoREGON RULE

CO.

l|l|l|M|l|l|l

1

U.S.A.

2

3

4