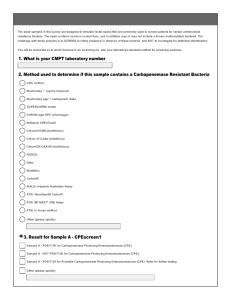

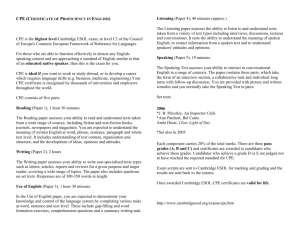

Report of the CUNY Proficiency Examination Task Force

advertisement