Document 11146117

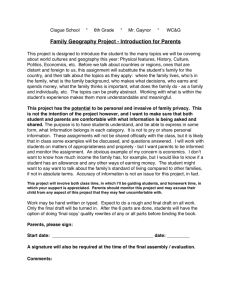

advertisement