INSTITUTIONALIZING AND DIFFUSING INNOVATIONS WP 1928-87 IN

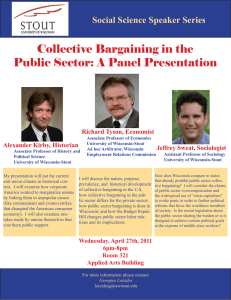

advertisement