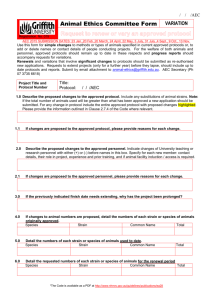

ON

advertisement