Document 11133443

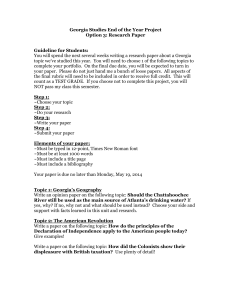

advertisement