BEYOND THE BIG TOP

advertisement

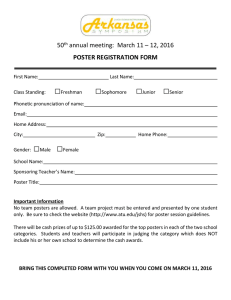

Some circus posters did not send any feelings of happiness or friendliness. Czerniawski, known for blurring the lines between painting and design, often represented memories and contemporary issues within his symmetrical and surrealist posters. The painted title conveys both personal and disruptive sensibilities, and the acrobat symbolizes the Poles’ BEYOND THE BIG TOP irritation of the turmoil caused by the “twisted” Soviet government. Jan Mlodozeniec (1975) Mlodozeniec often created work that was reminiscent of wycinanki folk style, an art of papercutting. This poster utilizes that style and pays attribute to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s “Moulin Rouge: La Goulue” poster. Much THE ART OF THE POLISH CIRCUS POSTER like the Moulin Rouge, the Soviet government used the circus in Poland to celebrate its stability and progress. In the industrialized and urbanized United States, advertising artists displayed the excitement of the politically-neutral circuses by painting vibrant, realistic illustrations of elephants, bears, and ringmasters in layouts with the punch line “The Greatest Show on Earth.” These pieces generally look similar to the examples below. LIONS, TIGERS, AND CLOWNS – OH MY! In 1956, the first major Soviet circus began touring in Poland. As the Soviets built their nuclear arsenal, the “cyrk” (which translates to “circus”) brought cheer to Poland and other satellite states. As a lively event with universal appeal, the circus conveyed the idea that the Soviets were a people of peace, equality, and happiness. “The friendly, multinational, space-age circus was presented as proof that the Soviet Union was the world’s only exporter of the humane, anti-imperialist, and progressive socialist ideology and therefore, its best guarantor of international peace” (Miriam Neirick). Despite its content, the circus gave artists the chance to design unique event posters. Beginning in the 1960s, the Polish State Entertainment Agency commissioned poster artists to create promotional pieces for the circus. Warsaw’s Jan Mlodozeniec (1929-2000) and Wroclaw’s Jerzy Czerniawski (1947-present) were two of many artists who took the opportunity to cover the streets with their illustrative, abstract designs that sometimes sent subliminal political messages to the public. Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey (1900) Jan Mlodozeniec (1975) Because of Mlodozeniec’s use of bright color, the bold typography stands out the most in this design. The “Y”, which may be interpreted as a symbol of Polish resistance, sends questions about the objectives of both the clown and the circus. Jerzy Czerniawski (1977) Unlike most circus posters, Czerniawski included text within this 1977 piece. The text at the bottom translates to the first stanza of William Blake’s “The Tyger.” The poem examines the root of evil by questioning what or who could make such a horrific creature – perhaps a reflection on the Soviet’s control of Poland. Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey (1940) Hubert Hilscher (1979) Waldemar Swierzy (1970) THE HISTORY OF THE POLISH POSTER In 1944, during WWII, Poland became a satellite nation of the Soviet Union. That year also marked the beginning of the Golden Age of the Polish Poster. Due to the lack of consumerism in socialist Poland, the posters were evaluated not in terms of sales but terms of design. Talented designers, who were trained in fine art, developed individualistic styles that set the posters apart from the rest of the world. The Soviet government deemed poster design an effective means of promoting socialist propaganda. Although the government prohibited revolutionary styles and symbols, the artists became the spokespeople of a dissatisfied nation by using subliminal messages in their designs. Polish poster art was at its peak in the late 1960s. Artists were featured at the First International Poster Biennale in Warsaw in 1966 and at the 1968 opening of the world’s first poster museum – the Poster Museum at Wilanów. Maciej Urbanjec (1970) Jan Sawka (1975) Jan Lenica (1976) Andrzej Pagowski (1978) The posters were crucial in the 1980s Solidarity movement, which lead to the fall of communism in Poland in 1989 and the rise of a market economy that introduced commercial prints. Although that level of Polish poster art diminished in production, the posters remain symbols of the nation’s sociopolitical distress for more than 30 years and examples of some of the best design in world history. Courtney Sabo | Graphic Design | The Frank Fox Polish Poster Collection at Drexel University and the Kenneth F. Lewalski Polish Posters Collection at Drexel University | Drexel University Research Day 2015 Jerzy Czerniawski (1975)