Document 11129484

advertisement

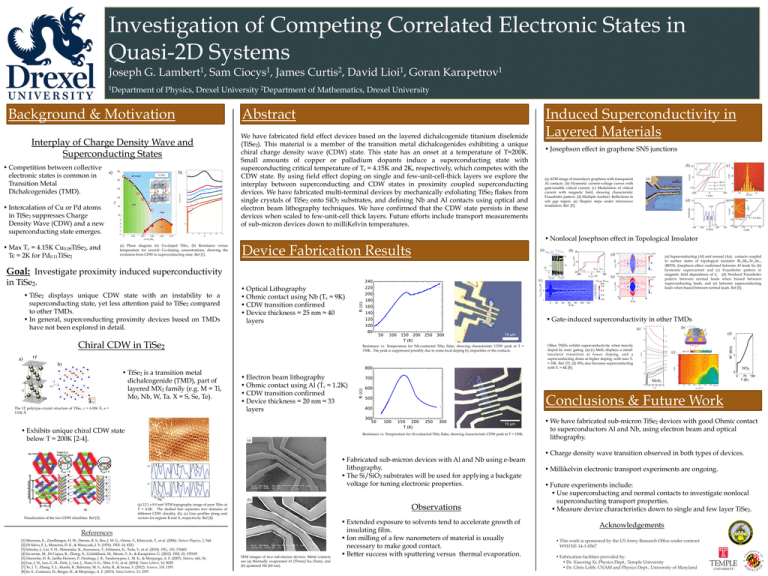

Investigation of Competing Correlated Electronic States in Quasi-2D Systems Vol 446 | 1 March 2007 | doi:10.1038/nature05555 David 1 Lioi , Goran LETTERS 1 Karapetrov of Physics, Drexel University 2Department of Mathematics, Drexel University Hubert B. Heersche1*, Pablo Jarillo-Herrero1*, Jeroen B. Oostinga1, Lieven M. K. Vandersypen1 & Alberto F. Morpurgo1 Abstract Induced Superconductivity in Layered Materials density only in the bottom one or two layers. For single layers, the Graphene—a recently discovered form of graphite only one 1 position of the resistance maximum corresponds to the gate voltage atomic layer thick —constitutes a new model system in condensed at which the Fermi energy is located at the Dirac point, VD, and we matter physics, because it is the first material in which charge typically find that jVDj , 20 V. We unambiguously determine the carriers behave as massless chiral relativistic particles. The anom2,3 single layer character of a device by quantum Hall effect (QHE) alous quantization of the Hall conductance , which is now under4,5 measurements. Because the superconducting proximity effect stood theoretically , is one of the experimental signatures of the requires two closely spaced electrodes, we can only perform magnepeculiar transport properties of relativistic electrons in graphene. toconductance measurements in a two terminal configuration. In Other unusual phenomena, like the finite conductivity of order 2 general, the conductance, G, measured in this way is a mixture of 4e /h (where e is the electron charge and h is Planck’s constant) at NATURE | Vol 446 | 1 March 2007 2 longitudinal and Hall signals, but at high fields G < jGHallj (this the charge neutrality (or Dirac) point , have come as a surprise and approximation is exact at the Hall plateaus19). Indeed, the measureremain to be explained5–13. Here we experimentally study the ment of G versus VG at B 5 10 T shows clearly identifiable Hall plaJosephson effect14 in mesoscopic junctions consisting of a grab /ha (Fig. 1d), characteristic of the teaus at half-integer multiples of 4e2(b) phene layer contacted by two closely spaced superconducting (c) 75 QHE in single layer graphene2,3. This demonstrates that, even in 30 electrodes15. The charge density in the graphene layer can be controlled by means of a gate electrode. We observe a supercurrent 20 that, depending on the gate voltage, is carried by either electrons in 0 I a b (a) (a)conduction AFM image graphene with transparent 1 µm the bandoformonolayer by holes in the valence band. More imporVG = –50 V 10 Al contacts. (b) Hysteretic current-voltage curves with tantly, we find that not only the normal state conductance of VG = –7.5 V graphene is finite,critical but alsocurrent. a finite supercurrent can flow at zero –7 5 gate-tunable (c) Modulation of critical VG = +1 V charge density. Our observations shed light on the special role of 0 current with magnetic field, showing characteristic – 250 0 250 –10 0 10 B (mT) time reversal symmetry in graphene, and demonstrate phase I (n A ) Fraunhofer pattern. (d) Multiple Andreev Reflections in coherent electronic transport at the Dirac point. c 1.2 d 60 100 (d) (e) 14,16 sub gap region. (e) Shapiro steps under microwave Owing to the Josephson effect , a supercurrent can flow through Ref. [5]. 2 ∆/3 a irradiation. normal conductor placed between two closely spaced supercon30 0 . 0 1 ducting electrodes. For this to happen, transport in the normal con0 ductor must be phase coherent and time reversal symmetry (TRS) –100 d 0.8 must be present. In graphene, the Josephson effect can be investigated f = 4 .5 G H z 1/2 c – 30 P (a.u.) B = 10 T B = 35 mT 15 2.0 in the ‘relativistic’ regime , where the supercurrent is carried by 2 .5 ∆ T = 3 0 m K Dirac electrons. However, it is not clear a priori that graphene can T = 100∆ m2 K – 60 – 150 75 – 75 0 – 7 0 0 3 5 0 350 700 – 0 2 .0 support supercurrents, because other quantum interference pheV (µV) 1.5 I (n A) nomena that require both phase coherence and TRS were found to 1 .5 Figure 2 | Josephson effect in graphene. a, Voltage, V, versus current bias, 17 be absent or strongly suppressed in previous experiments . Below we I, characteristics at various VG, showing a modulation of the critical current. 1 .0 1.0 show experimentally that the Josephson effect in graphene is a robust Inset, current bias sweeps from negative to positive (red) and vice versa (blue), showing that the asymmetry in the main panel is due to hysteretic phenomenon, and argue that its robustnessLetter is intimately linked to REPORTS 0 .5 behaviour (the retrapping current is smaller thantransistor theoperations switching current, as (15) suggests that interesting graphene’s unique electronic structure. Nano Letters Letter b, Colour-scale 0.5 Superconducting Dome in a Gate-Tuned basic physical properties may be revealed by usingof representation is typical for an underdamped junction). (a) Single- and few-layer 0 .0 the EDL dielectrics (11, 16–18). To make our de(b) graphene Josephson junctions are fabricated isolated flakes of MoS from a dV/dI(I,B) is zero, vices, thatweis, thethinsupercurrent 2030 mK 0(yellow-orange – 40 at T–5 20 2superconducting – 40 – 20 0 0 40 Band Insulator proximity effect between Pb and Bi2Te3 bulk 2H-type single crystal (Fig. 1A) by the 1 (d) region, and red corresponds to finite dV/dI). The critical current Scotch tape method widely usedexhibits in graphene a VG (V) established along VG (V) on oxidized Si substrates by mechanical exfoliation of bulk graphite , J. T. Ye, the * Y. J. Zhang, R. Akashi,direction Bahramy, Arita, Y. Iwasa thickness ofR.normal the Bi Te3*(Au) flake. research (19, 20) and transferred them onto the (a) Superconducting (Al)M. S.and contacts coupled c , Differential series of oscillations described by2 a Fraunhofer-like pattern. surface of HfO grown by atomic layer deposiThese observations were interpreted of ofamanywidely followed by optical microscope inspection to locate the thinnest A dome-shaped superconducting region appearsin in theterms phase diagrams unconventional tion on a Nb-doped SrTiO substrate. We selected resistance, dV/dI, versus V, showing multiple dips 22by theAndreev superconductors. In doped band insulators, however, reaching optimal insulator superconductivity to extended surface states of topological Bi1.5reflection Sb Teby1.7 Sebelow atomically flat thin0.5 flakes examining their 1.3 proximity effect, including the bulk of the flakes. fine-tuning of carriers has seldom been seen. We report the observation of a superconducting graphitic flakes, and electron beam lithography to define electrical optical occur micrographsat (21)values and patternedof them into Figure 1 | Sample characterization. a , Atomic force microscope image of a the superconducting energy gap. The dips in dV/dI dome in the temperature–carrier density phase diagram ofin MoSthese , an archetypal band insulator. By a Hall bar configuration (Fig. 1B), which acts as Becasue the bulk transport can be substantial materials, quasi-continuous electrostatic carrier doping through a combination of liquid and (BSTS). Josephson effect confirmed between (b) transistorleads channel (11, 16).by A droplet of ionic d,solid a.c. aAl Josephson effect. The 5plausible. 2D/en, where nachieved iselectrodes. an integer number. contacts. Figure 1a shows an atomic force microscope image of a single layer graphene device twoV superconducting We gating, weis revealed a large enhancement in the transition temperature T occurring at optimal thisbetween interpretation However, considering that the liquid (DEME-TSFI) (21) was applied onto the doping Shapiro in the chemicallysteps inaccessible low–carrier density regime. This observation appear indicates thatwhen in the I–V characteristics is irradiated surfacethe of the sample thin flake covering the side gate have fabricated deviceshysteretic with electrode separations incoupling the 100–500 nm. extremely extended Josephson in band these reports is not supercurrent (c) Fraunhofer pattern in typical device. We use as superconducting contacts a Ti/Al bilayer the superconducting dome may arise even range inand doped insulators. electrode (Fig. 1C). A voltage applied between with microwaves. In the example, we applied 4.5 GHz microwaves, the thus formed liquid gate (LG) andresulting the channel well understood, the nonlocal effect we report here may have b , Schematic representation of graphene between superconducting n many unconventional superconductors (4, 5). Except in certain cases (4, 6), however, drives either anions or cations onto the channel (10/70 nm). Titanium ensures good electrical contact to graphene, magnetic field ofInset, Ic.doping (d) Nonlocal Fraunhofer inthedependence 9.3 mV voltage colour-scale plot the characteristic chemical to achieve low carrier den- showing transition temperature T has asteps. max- using surface under positive or negative bias, respecbeenininvolved in(1–3), the observation. (e) electrodes. The two electrons a Cooper pair entering graphene into sities1/2 results in go nonuniformity or phase separation. tively. The ions and induced carriers (~10 cm ) imum as a function of external parameters ; a.u., arbitrary units) dependence of the a.c. microwave amplitude (P and Al establishes a sufficiently high critical temperature to enable the In summary, we demonstrated a surface-dominant Josephson Other systems exhibiting optimal doping of the such as chemical doping or pressure; in cuprate right beneath form an equivalent capacitance of patternby between normal leads when biased between superconducting state include two-dimensional families, this so-called superconducting dome ~10 mF/cm , largeto enough for inducing superc , Twothe red and blue cones (see text). (c)observation of supercurrents in a dilution refrigeration set-up18. different K-valleys, represented Josephson effect (orange and red correspond respectively zero and finite effect in S−TI−S constitutes a direct (2D) electron systems at surfaces and and interfaces, conductivity at the interface (10–14). In addiarises upon junctions. the chemical dopingThis of the parent whose phase diagrams may be explored by apMott insulator (1). In band insulators, similar tion, we were able to modulate the carrier density superconducting and between superconducting Tof5the30existence mK and adominant small terminal resistance versus gate voltage, VdV/dI). unequivocal confirmation of a(e) surface G, at leads, behavior was observed at low carrier densities plying electric fields (7–9). In recent years, this (to ~10 cm ) using a high-k dielectric (HfO ) Before discussing their superconducting properties, we first char- REPORTS 28 electrostatic carrier doping has been effectively (4) where superconductivity is usually not favorback gate (BG), which remains effective after conduction in BSTS TI flakes and Josephson coupling magnetic B 5is35 mT, drive the electrodes into the normal state. vices (15),normal the more pronounced saturation ambipolar transport could be found flakes with regime where field, chemical doping plagued by to leads when biased between leads. Ref [6]. implemented by using ionic liquidsattohigh form an the able because of thein low density of states (DOS) freezing of the ion motion at a temperature acterize the devices with the superconducting electrodes in the norVchannels less intrinsicto electron (sulfur deficiency), nonuniformity. indicates well-behaved transistor operation. electrical double the layer (EDL) high capacitance below ~200 K. For carriers induced at the top confined the doping surface conducting when TI offlakes The aperiodic conductance fluctuations are due to random quantum (10–12). This method has produced carrier densurface of the MoS flake by the LG, the effecFigure 1D shows the transfer curves of a typ- where the barely metallic state in the p-channel After introducing carriers onto the channel arewasin proximity tosuperconductivity superconductors. The magnetic field mal state. Figure 1c shows the two-terminal resistance, R, versus gate sities that span the superconducting in high- tive BG capacitance is affected by two layers of still far from reaching hole ical double-gate device atelectron 220 K with a sourcesurface at 220 Kconductance, with different liquid-gatedome biases d , Two terminal interference of waves (see also Fig. 4). T cuprates (13, 14) and may be an effective tool dielectrics: HfO and the bulk of MoS flake. (16). To confirmof the the electrostatic operation of ofV the drain voltage V = 10 mV. For the n-channelmodulations , we measured the four-terminal sheet resistsupercurrent Al−BSTS−Al junction to access exotic superconducting states in other Using this double gating method, we could acV -dependence of R voltage, VG, for one of our samples. The strong LG, we performed a transfer curve measurement conduction, an on/off ratio of >10 ance R was reached as a function of temperature Tawhen the G at high magnetic field, B 5 10 T, and T 5 100 mK, showing G, versus V materials. cess a large of carrier densities n quasiG REPORTS –2 remained up to the superconducting critical field of the AlMoS (1012 range cm ) for biasing with either the liquid ionic gate (V ) with fast gate bias cycles2(fig. S1). The possibility device was being cooled downband to 2insulator, K (Fig. 2A)., be- ncontinuously We chose a typical and precisely, thereby avoiding a provides a first indication that the device consists of at most a few /h, of the series of steps values 4ewas of a chemical of reaction ruled out by repeatAt gate biases V the or the high-k back gateat (V half-integer ), with a channelelectrodes. <anomalous 1 V,Al−BSTS−Al we observed a negative the staging effect cause high mobility found in its–solid-state A voltage incharacteristic part of the TI outside the 2 0 (22), even in the low-density 2 vices (15), the more pronounced saturation at high ambipolar transport could be found in flakes with regime where chemical doping is plagued by resistance R > 1 gigohm in the off state. Com- ability and a negligible (~1 nA) leak current I , temperature derivative of R (dR /dT) for insu1 junction was nonlocally triggered along with modulations of the 0 /dT with V indiQHE in single graphene. VG 4.affects the carrier layers of graphene , since, owing to screening,Figure less intrinsic electron (sulfur deficiency), VDSoff nonuniformity. indicates pared BG, the LGlayer not doping only had state (> 1well-behaved gigohm). The transistor lating states. operation. The increase 2 of0 dR 2 (a) Nonlocal modulation voltage vwith thecorresponding to 10 times as well as a persistent ARTICLES x = 0.10 2 × 10 – 5 x = 0.08 x = 0.06 x = 0.05 1 × 10 – 5 x = 0.04 x = 0.03 x = 0.02 0 ARTICLES – 1 × 10 – 5 • Competition between collective electronic states is common in Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMD). 100 150 200 250 300 b) b 240 CuxTiSe2 Semi metal 10 x=0 200 0 3 M/H (300 K ) – 40 2 160 Cu Se c b a 1 x = 0.01 x = 0.02 Resistivity (mΩ cm) γ 120 Ti T (K) 4 x = 0.03 x = 0.04 • Intercalation of Cu or Pd atoms in TiSe2 suppresses Charge Density Wave (CDW) and a new Tc = 1.8 K (Fig. 1(b)). Authors that the mechanism of superconductivity is fundamentally superconducting state argue emerges. CDW 80 x = 0.06 0.1 x = 0.08 1 40 – 80 Metal x = 0.10 40 0 0.02 0.04 0.06 x in CuxTiSe2 0.08 x = 0.01 – 40 0.10 S (µV K – 1) 0 x=0 0 4 3 0.01 Figure 5 Summary of the composition-dependent properties in Cux TiSe2 . M/H (300 K), ρ (300 K)/ρ (6 K), electronic specific heat coefficient γ and Seebeck coefficient S(300 K) as a function of Cu composition x. The solid lines are guides to the eye showing the linear variation of the latter two quantities, whereas for the former two the lines reflect steep changes at low Cu content (0 < x < 0.02) and through the superconducting state (0.04 < x < 0.08). – 160 1 0 0 x = 0.03 – 120 SC 2 x = 0.08 – 80 50 100 100 150 200 150 250 T (K) 200 300 350 250 400 300 0.02 x 0.04 0.06 x in CuxTiSe2 0.08 0.10 T (K) Figure 2 Magnetization and transport properties of Cux TiSe2 . a, Cux TiSe2 M(T ) curves measured in a constant H = 0.5 T applied field, for 0 < x < 0.10. The solid lines illustrate how the CDW transition temperatures have been determined. (A small peak is seen around 60 K in a few of the measurements, which is attributed to an oxygen impurity trapped in the measurement system.) b, H = 0 temperaturedependent resistivity data for 0 < x < 0.10. Inset: Seebeck coefficient for x = 0, 0.01, 0.03 and 0.08. 2 546 c1 Device Fabrication Results c2 x in TiSe . c c −1 2 c2 0 c2 B B 2 I 0 B c2 c c2 ∗ c2 c2 Tc c2 ∗ c2 c 4+ 2− c2 c2 0.08 2 c2 c2 • Optical Lithography • Ohmic contact using Nb (Tc ≈ 9K) • CDW transition confirmed • Device thickness = 25 nm ≈ 40 layers Chiral CDW in TiSe2 c a) DS b) 549 nature physics VOL 2 AUGUST 2006 www.nature.com/naturephysics ©2006 Nature Publishing Group Untitled-1 6 21/7/06, 4:44:03 pm The 1T polytype crystal structure of TiSe2. c = 6.004 Å, a = Fig. 2. Å (a) Schematic crystal structure ofM. 1T polytype of TMDs where the transition metal atoms octahedrally IAVARONE et al. PHYSICALare REVIEW B 85, 155103 (2012) 3.536 coordinate by chalcogen atoms and the sample thickness of the unit cell in c direction is one sandwich [26]. (b) Crystal slightly increases by decreasing the temperature from 300 K, structure shows a broadofhump with a maximumthe at about ais1 trigonal prismatic and (a) a3 2H polytype, coordination the structure of TiSe2 [44]. (c) Schematic crystal 150 K. The maximum resistance of the sample at 150 K three times larger as that roompolytype temperature, indicating unit cell is two sandwiches thick [26]. (d)isOne sandwich ofat2H [71]. a • Exhibits unique chiral CDW state B below T ≈ 200K [2-4]. P H Y Sorder I C A transition L R E V Iinto E W a Lcommensurate ETTERS undergoes a second At ~105, 202 K TiSe2(2010) PRL 176401 a good stoichiometry. The resistivity at low temperature is ≈1 m! cm. For the Cu0.05 TiSe2 and Cu0.06 TiSe2 crystals, the in-plane resistivity is metallic with a residual resistivity ratio ρab (300 K)/ρab (4 K) = 4 and 4.5 for the two samples, respectively. The resistivity just above the superconducting transition is 100 µ! cm for the Cu0.05 TiSe2 crystal and 70 µ! cm for the Cu0.06 TiSe2 crystal. The corresponding superconducting critical temperatures are Tc = 2.0 and 3.0 K. Low-temperature scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and spectroscopy (STS) have been performed at T = 4.2 K using a Unisoku UHV STM system, with a base pressure of 1 × 10−10 Torr. The samples were cleaved just before cooling down. We used Pt-Ir tips in all of our experiments, therefore the tunneling conductance between a normal electrode (tip) and a sample provides, in the limit of low voltages, the electronic density of states of the sample. All STM and STS measurements reported in this paper have been performed at 4.2 K and therefore the samples are in the CDW state but not in the superconducting state. week ending 22 OCTOBER 2010 aobserved a3 2a0 × 2a0 × 2c0 CDW state without an intermediate incommensurate state, by, neutron 1 rectly the interplay between chirality and transport in diffraction [11], electron diffraction [27], and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) [28]. A A a2 electron systems. Our findings could also pave the way driving force of the instability has been under debate for decades, during this time several Ia1 Ia2 (b) I towards theorinvestigation of charge helicity and external hypotheses were proposed: (i) the formation of an excitonic insulator [12],[16],[29] evena3 (ii) fields. an excitonic condensate, (iii) an antiferroelectric mechanism [17]-[18], (iv) the involvement of a We thank K. Yamaya and T. Toshima for providing band-type Jahn-Teller effect [19]-[20], (v) an indirect Jahn-Teller effect [21] (c) Ia2 combination Ia1 and the advice on sampleIa3preparation. We also thank K. Inagaki, of (i) and (iv) [22]-[23],[26]. Up to now, no unambiguous and conclusive explanation has been T. Matsuura, and H. Nobukane for measuring the electriIII. STM CHARACTERIZATION OF THE CDW STATE given. However, there is a general consensus that the CDW transition in cal TiSeproperty by fruitful discussions. And we thank 2 is not driven and for 2a0 Atomically resolved images were acquired in the constant current mode with a constant voltage between sample and 2 STM topography (a) 12.1 xFIG. 8.91. nm pure TiSe2 at (Color online) (a) 12.1 × 8.9 nm2 STMimage topographyof image tip. Figure 1(a) shows a 12.1 × 8.9 nm2 STM image of pure of pure TiSe2 acquired at T = 4.2 K. Scanning parameters are I = TiSe2 . All surface Se atoms of the hexagonal surface layer Tare= 4.2K. The dashed line separates two domains of 300 pA and V = −0.2 V. The dashed dark line shows the transition clearly resolved with a strong superlattice modulation 2a0 × between two different domains. (b)(b), Line profiles along the unit vectors along unit different CDW chirality. (c) Line profiles 2a0 clearly seen in direct space. a1 , a2 , and a3 in the region B of image (a). Iai is the normalized A closer Visualization of the two CDW chiralities. Reflook [3].at the amplitude of the modulation along vectorsamplitude for regions and A,along respectively. Ref [4]. along of the STMBcorrugation ai . (c) Line profiles the three directions reveals that the amplitude along the the unit vectors a1 , a2 , and a3 in the region A of image (a). crystallographic direction a2 has higher intensity than that 2 along a3 and a1 , in the top region B of the topography image. The same analysis reveals instead Ia1 > Ia3 > Ia2 The same conclusion can be drawn from the twoin the bottom of the image [portion A of Fig. 1(a)]. We dimensional Fourier transform (2DFT) of the region A [see name the phase in region A clockwise and that in region B Fig. 2(a)] and region B [see Fig. 2(b)].19 The 2DFT shows anticlockwise, where clockwise and anticlockwise indicates in both cases two sets of peaks. The outer peaks corresponds [1] Morosan, E., Zandbergen, H. W., Dennis, B. S., Bos, J. W. G., Onose, Y., Klimczuk, T., etpeaks al. (2006). Nature Physics, 2,is544. the direction of increasing amplitude. These two domains to the Bragg of the Se lattice whose wavelength a0 , cannot be superimposed on each other with simple rotational the inner peaks correspond to the CDW superlattice peaks [2] Di Salvo, F. J., Moncton, D. E., & Waszczak, J. V. (1976). PRB, 14, 4321. transformation, but they are mirror images of each other. This whose wavelength is 2a0 . The three sets of CDW peaks have 11 [3] Ishioka, J., Liu, Y. H., Shimatake, K., Kurosawa, T., Ichimura, K., Toda, Y.,theet al.different (2010). PRL,in105, 176401 observation in agreement with previous reports indicates intensities the two images. The 2DFT of region of the CDW inM., TiSe2Moore, . The line profiles the A in the topography image reported Fig. 1 shows that the [4] Iavarone, X., state Golalikhani, S. A.,along & Karapetrov, G. (2012). PRB, 85,in155103 0 M., Di Capua, R., Zhang,chiral three directions in region B are reported in Fig. 1(b) while CDW peaks increase in intensity clockwise with a normalized [5] Heersche, H. B., Jarillo-Herrero, P.,those Oostinga, J. B., Vandersypen, F.: (2007). related to the region A are reported in L. Fig.M. 1(c).K., The& Morpurgo, amplitude of Iq1A. : Iq2 Iq3 = 1.0 :Nature, 0.33 : 0.45,446, while56. in the intensities of theShin, modulations areet Ia1 al. : Ia2(2014). : Ia3 = 0.3Nano : 2DFT of region increase in intensity anticlockwise with [6] Lee, J. H., Lee, G.-H., Park, J., Lee, relative J., Nam, S.-G., Y.-S., Letters, 14,B they 5029. 1 : 0.7 in region B and Ia1 : Ia2 : Ia3 = 1 : 0.5 : 0.7 in region a normalized amplitude of Iq1 : Iq2 : Iq3 = 0.46 : 1.0 : 0.7. [7] Ye, J. T., Zhang, Y. J., Akashi, R., Bahramy, M. S.,have Arita, & Iwasa, (2012). Science, 1193. and analysis have been performed A. These profiles been R., normalized to the Y. maximum The same338, measurements amplitude alongA. each direction. The profiles can slightly for the Cu0.05 TiSe2 and Cu0.06 TiSe2 crystals. In Fig. 3(a), a [8] Jo, S., Costanzo, D., Berger, H., & Morpurgo, F. (2015). Nano Letters, 15, 1197. change from location to location especially when approaching 15 × 6.3 nm2 STM image for Cu0.05 TiSe2 is reported. The 4 FIG. 4 (color). Schematic representation of (a) left-handed chiral CDWs and (b) right-handed chiral CDWs in a TiSe CDW unit cell in real space and (c) typical 2D CDW. Charge References concentration is indicated by the deeply colored part. The colors correspond to the colored CDW q vector in the inset. In a CDW unit cell, the density peaks of three CDW are shifted at intervals of 2c =3. If we look at one layer, the different intensities of three CDWs form a low symmetry structure. There are two phases caused by difference in stacking direction (red-blue-green or redgreen-blue). As with cholesteric liquid crystals, the stacking −2 *Corresponding author. tanda@eng.hokudai.ac.jp images of two sub-micron devices. Metal contacts [1] A. D. Dolgov, Phys. Rep. 222, 309SEM (1992). 3 He (a) thermally evaporated (World Al (55nm)/Au (5nm), and [2] G. E. Volovik, Exotic Properties ofare Superfluid (b) sputtered Nb (60 nm). Scientific, Singapore, 1992). [3] A. P. Mackenzie and Y. Maeno, Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 657 2 2 *To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: yejianting@ap.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp (J.T.Y.); iwasa@ap.t.u-tokyo.ac. jp (Y.I.) 2D 2 LG G s s LG D2efficiency C2 the barely gate (the change of channel IDS versus supercurrent. the gradual formation of degenerate carriers VDS characteristic in the outputvoltage op- catesonto junction The across the Al−BSTS−Al metallic statecurrent in the p-channel Figure 1D shows the transfer curves of a typ- the where After introducing carriers the channel versus gate voltage DI ), but also created an eration (Fig. 1E) of a typical MoS2 EDL tran- and enhanced mobility at low temperatures. The DV reaching 1 i , as a function of the bias current I applied between A and was still far from hole superconductivity ical double-gate device at 220 K with a sourcesurface at 220 K with different liquid-gate biases wascorroborates also modulated by thechannel nonlocal at the A1B1the D1CPO A1additional BThe 1 1 Kavli of Nanoscience, Delft University Technology, Box 5046, 2600 GA, Delft, Netherlands. surface bias shows current metallic transport (posp-channel when a 1negative VG wasjunction sistor (EDLT) the more pronounced Figure 2. Institute (a) A scanning electron micrograph of theofdevice and (16).This To confirm the electrostatic drain voltage VDS = field 10 mV. For the n-channel , 1weV)measured the opfour-terminal sheet resist-V. The enhancement LG<junction. itive dR n-channelof (0 < VVLG applied. ambipolar transport indicates thatoperation than p-channel of s/dT) at VLG ≥ 1effect Au−BSTS−Au This mirage Fraunhofer can be B , and magnetic B. i , is the fraction of the modulation *These authors contributed equally to this work. 1 A B D C measurement setup used in this study, which consisted ofconduction, Au an on/off ratio of >10 1 14 1 1 LG iswe effective in shifting the Fermicurve level EFmeasurement eration (–0.6 < V metallicity continues –0.2V), performed a transfer ance was reached theLG, function with of temperature T whenwith thefurther increase of VLG, LG < R s as a consistent explained only in terms of existence of robust the transfer characteristics. Compared with the the down and superconductivity emerges atsurface V = 4 V. bothCgate the and conduction bands iA1with 10 the nA) flowing between andfast vbias exhibits electrodes (yellow) and Al electrodes (blue), overlaid on a BSTScurrent flake. (fig. S1). The possibility for biasing either liquid ionic gate (VLG) toDaccess device was being cooled to 2 K (Fig. 2A). B1 (= 1with 1. valence D2C2 cycles 10T0c shows LG n-channel operation observed in monolayer de- The (16). An enhanced p-channel with more balancedconducting transition temperature clear 56 channels, which extend to the sides of the TI. TheVLG of a chemical reaction was ruled out by repeatAt gate biases V or the high-k back gate (V ), with a channel < 1 V, we observed a negative BG LG Fraunhofer-type variations. The blue-colored (red-colored) inside IA1B1 (IC1D1) and VA2B2 (VC2D2) are the bias current and voltage 1 local and nonlocal Fraunhofer diffraction-type modulation of ability and a negligible (~1 nA) leak current I resistance R temperature derivative of R > 1 gigohm in the off state. Com, (dR /dT) for insuNature Publishing Group (resistive) DS ©2007 G s s region of the pattern denotes the pair-conducting difference between a pair of the Al (Au) electrodes, respectively. (outside) x and pared with the BG, the LG not only had 10 times as well as a persistent off state (> 1 gigohm). The lating states. The increase of dR /dT with V indis LG the junction critical current and differential resistance with state of the Al−BSTS−Al junction. (b) Nonlocal modulation voltage the gate efficiency (the change of channel current IDS versus VDS characteristic in thepersistent catesmodulation the gradual formation degenerate shows carriers nice fits to output op- field y denote the spatial coordinates viewed from above. (b) Current− of theofenvelope vversus to DS iC1D1,B1A1 as a function of the bias current IC1D1 B2A2 corresponding gate voltage DI eration (Fig. 1E) of a typical MoS2 EDL tran- and enhanced mobility at low temperatures. The DVG ), but also created an voltage characteristics of the Al−BSTS−Al junction at the bath model of a edge-stepped nonuniform supercurrent density additionalbetween p-channelCwhen negative sistor pronounced channel surface shows metallic transport (pos- 0 applied magnetic field (EDLT) B. iC1Dcorroborates , is thethe morethe G was 1 anda D 1, and V 1 B1A1 temperature of 10 mK, where the blue/red curve and arrow denote the This ambipolar Fig. 1. MoS2-based EDLT device and its transistor properties. on the oproughitive side BSTS flakes. of This strongly (A) dRssurfaces applied. transport indicates that n-channel (0 < VLG < 1 V) than p-channel /dT) at VLGof≥ 1the V. The enhancement Ball-and-stick model of the layered 2H-type MoS2 single of iC1D1 (= 100 nA) flowing between B1 and A1. vB2A2 also r crystal. (B) Optical micrograph of a typical MoS2 device un- 0 suggests that the Josephson coupling in a TI is established sweeping direction of IA1B1 from left/right to right/left. IcA1B1 andfraction theIALG is effective in shifting the Fermi level E eration (–0.6 < V metallicity continues with further increase of V < –0.2V), consistent with , F LG LG 1B1 transmission light illumination. (C) Double-gate device exhibits variations. Temperature increasecharacteristics. due to Joule Compared with the and superconductivity emerges at Vthat to accessFraunhofer-type both the valence and conduction bands the transfer 4 V.topologically der LG =are through the surface conducting channels and measurement configuration. VD (D) Transfer curve of trandenote the critical and retrapping currents, respectively. (c)heating The altered the de- This (16). An enhanced p-channel more balancedpeakn-channel Thestudy transition temperature Tc shows clear Vfor around Bobserved = 0. in monolayer shape with of the primary of vB2A2 operation LG confirming sistor operations by accumulating carriers by EDL top liquid protected. provides a unique method DS G • Gate-induced superconductivity in other TMDs Figure 1. A false-colored schematic diagram of devices with nonlocal measurement configurations, where the electrodes A and B are used as a source and a drain, respectively, for the bias current IAB and the voltage difference VCD are monitored between electrodes C and D. The normal conductor of the device consists of (a) conducting bulk, (b,c) insulating bulk, and conducting surface. The conducting surface in (c) is superconducting between the electrodes A and B. The arrows 15 µm denote the current directions in the normal conductors. The crosssection between x1 and x2 corresponds to the dotted x1 −x2 line in Figure 2a. • Fabricated sub-micron devices with Al and Nb using e-beam lithography. • The Si/SiO2 substrates will be used for applying a backgate voltage for tuning electronic properties. Observations • Extended exposure to solvents tend to accelerate growth of insulating film. • Ion milling of a few nanometers of material is usually necessary to make good contact. • Better success with sputtering versus thermal evaporation. (b) (a) Nano Letters (d) gate (red: ramping V up; blue: ramping V down) and HfO differential resistance dVA2B2/dIA1B1 of the Al−BSTS−Al junction, bottom solid gate (green), both at 220 K. (E) Output curve of Josephson coupling via the topological surface – 10conducting 0 the thin-flake MoS EDLT with both electron (0 < V < 1 V) and hole (–0.6 < V < –0.2 V) channel. obtained Other by numerically differentiating the Isuperconductivity 20 – 40Well-behaved–saturation 20 at large V 0was found in the dominating TMDs exhibit when heavily A1B1−VA2B2 characteristics at channels, which in turn provides a solid basis for exploring electron transport. For each V , we measured the two overlapping I curves with forward and backward distribution of the bias current IC1D1 via the BSTS TI surface. ( V ) V scans of V . G Majorana Fermionic excitation states by adopting TI/superdifferent doped values of perpendicular field(a)-(c) B, as a function B by cionic magnetic gating. MoSv2Bof2Adisplays metalvanished if ICa < IcA1B1 (= −IcA1B1). For IC1D1,B1A1 < IcA1B1, conductor 2 1D1,B1A1 and IA1B1 normalized by IA1B1(0). (c) heterostructures. 1193 www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 338 30 NOVEMBER 2012 Figure 3 | Bipolar supercurrent transistor behaviour and finite became i × R as shown in Figure 4b, where R insulator transition at lowervB2Adoping, and a C1D1,B1A1 B2A2 B2A2 2 supercurrent at the Dirac point. a, Colour-scale plot of dV/dI(VG,I). Yellow ASSOCIATED CONTENT = 80 Ω was the normal-state resistance between B2 and A2. The means zero, that is, the supercurrent region, and finite dV/dI increases via superconducting dome at higher doping, with max T c the Josephson coupling occurs dominantly via the surfaceappearance of this nonlocal feature indicates the existence of a S Supporting Information orange to dark red. The current is swept from negative to positive values, and * conducting layer. Ref. One would not WS expect this nonlocal mirage topologically protected conducting surface on our BSTS flake25 ≈ 10K. [7]. (d) becomes superconducting 2 also is asymmetric owing crystalline to the hysteresis associated with an underdamped Normal-state properties of the BSTS flake, overFraunhofer effect for the case of N, sandwiched betweenwith theJosephson coupling across it. junction (seeJosephson also Fig. 2ajunction, inset). The top axis shows the electron density, n, as damped characteristics of the differential with T ≈ 4K [8]. WS2 (positive) VG two S electrodes Ac and B with finite bulk conduction becauseThe in primary lobe of vB2A2 in Figure 4b exhibits a typical obtained fromjunction geometrical resistance of the Al−BSTS−Al by acconsiderations measurements,1. For large negative c this case the current IAB (>IAB) would mostly be confined Fraunhofer-type modulation but differs from that of vD2C2 in Fraunhofer interference pattern for aisnonuniform supercurrent the supercurrent carried by hole (electron) Cooper pairs. The density, fits to the uniform-current Fraunhofer diffraction for between A and B as in Figure 1a. Only when the conductance Figure 4a; the differential resistance is highly enhanced along 25 different field periodicity, estimation of the nonlocal current, edge of the critical current. This difference resulted from in a TI is predominated by the surface conducting layer, thethe ©2007 Nature Publish MoS and suppression of Ic due to bias-induced Joule heating. This the temperature increase due to Joule heating generated by2the situation depicted in Figure 1c is expected. material is available free of charge via the Internet at http:// biasitscurrent IC1D1(≃ 43 IB1A1). IcC1D1 ≃ 3 μA in Figure 4b A scanning electron micrograph of the actual device and pubs.acs.org. c to IB1A1 ≃ 70 nA. The Joule heating due to IC1D1 measurement configuration is shown in Figure 2a. The corresponds setup Fig. 2. Transport properties of the thin-flake MoS2 EDLT. (A) Temperature responds to the logarithm of the sheet resistance Rs (W). (D) Normalized was Al transferred to the BSTS flake between B2 and A2 with consisted of a 115 nm-thick BSTS crystal flake, overlaid with dependence of the channel sheetthe resistance Rs at different VLG gate biases superconducting transition Rs/Rs (15K) as a function of temperature for difAUTHOR ranging from 0 to 6 V (indicated on the right). (B) Temperature dependenceINFORMATION ferent gate voltages. The Tc is marked as a circle at 90% of the total transition. carrier temperature in the BSTS flake reaching a temperature of and Au electrodes. The BSTS flake, grown using the self-flux of the channel sheet resistance Rs at VLG = 1 V and different VBG’s showing a Both VLG and VBG are varied; for a given VLG, we show the evolution of the n2D =Ic6.7 × 1012 cm−2Corresponding transition with increasing VBG. All data corresponding to the same VLG are . For each VBG, we marked Author ∼115 mK (see Supporting Informationmetal-insulator 7). Thetransition valueat of B A1 method,26,27 was mechanically exfoliated onto a Si substrate the corresponding n2D measured by1 the Hall effect at 20 K. (C) Phase dia- shown with the same color. The dashed arrows indicate the order of increasing *E-mail: gram nA showing phases as a hjlee@postech.ac.kr. function of VBG from –4 to 2 V in ∆VBG = 2 V. (Upper panel) For VLG between 4 and 5.5 V, (≃ 70 nA) was suppressed below 110 attheTevolution = 10of different mK electronic capped with a 300 nm thick SiO2 layer. Details of the BSTS carrier density n2D. The phase diagram shows an insulating (n2D < 6.7 × Tc increased with increasing VBG; (bottom panel) for VLG = 6 V, Tc decreased 28 (without Joule heating) as the carrier temperature rose 115 (6.7 ×to 1012 < n2D < 6.8 ×Notes 1013 cm−2), and a dome- with increasing VBG because the corresponding n2D had reached the peak of 1012 cm−2), a metallic crystal growing are described elsewhere. The Au electrodes c(n2D > 6.8 × 1013 cm−2), where the color cor- the superconducting dome. like superconducting phase The authors declare no competing financial interest. mK due to Joule heating, which led to the condition ΔI (0) B1A1 were deposited on the BSTS flake by combining electron(e)< iB(5 , so that enhancement of the1194 differential resistance at the30 NOVEMBER 2012 VOL 338 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org 1A1 beam patterning, sequential e-gun evaporation of a Ti/Au ACKNOWLEDGMENTS edge of the critical current recurred, as discussed in Supporting nm/350 nm thick and 400 nm wide) bilayer, and lift-off. Information 3 in association with Supporting Information This work was supported by the National Research Foundation Immediately prior to the Ti/Au deposition, the surface of the Figure S3. (NRF) through the SRC Center for Topological Matter (Grant BSTS flake was Ar ion-beam cleaned for 20 s with a beam Fraunhofer modulation has been reported over an extended 2011-0030046 for H.J.L., Y.S.S., and J.S.K.), the GFR Center power of 4 W (= 400 V × 10 mA). The superconducting Al in Bi2Se3 from the Pb−Bi2Se3 interface by the proximity volume for Advanced Soft Electronics (Grant 2011-0031640 for H.J.L.), electrodes were prepared in a similar fashion as theeffect. Au19 The same group has also reported a strong the Basic Science Research Program (Grant LG LG 2 2 LG LG DS LG DS DS sectional view, along with the probable current profile via the surface and the bulk. The cross-section is drawn through the middle of the N conductor along the x-axis, which corresponds to the dotted x1−x2 line in Figure 2a. Electrodes A and B are used as the source and drain, respectively, for biasing current IAB, and the potential difference VCD is monitored between the electrodes C and D. Figure 1a depicts the case in which the N layer is normal-conducting with finite bulk conductivity. In Figure 1b, the N material consists of an insulating bulk and a conducting surface layer that uniformly covers the entire bulk. This mimics the conduction in a TI flake with normal-metallic contact leads. The situation of Figure 1c is identical to that of Figure 1b with the exception that the electrodes A and B are replaced by superconductors. In Figure 1a, with the electrodes C and D widely separated (>1 μm) from the electrodes A and B VCD is expected to be negligible as the diffusive current flow is confined primarily between A and B. In Figure 1b, IAB injected from A spreads out across the entire surface, that is, top, bottom, and four sides, which results in a nonvanishing value of VCD.25 If the electrodes A and B are superconducting and arranged sufficiently close to one other as in Figure 1c, Josephson coupling is established 10 µm through the surface conducting layer between electrodes A and B. For IAB less than the superconducting critical current IcAB, the entire current IAB injected from A is confined only between A showing CDW T ≈c 150K. andcharacteristic B, showing vanishing VCDpeak . For Iat AB > IAB, however, the surface conduction between A and B becomes resistive so that IAB injected from A spreads out across the entire surface before being recovered at the drain B, as depicted in Figure 1b, and induces a nonvanishing value of VCD. Thus, in this case, VCD versus B reveals a replica of IcAB versus B, which confirms that (b) N. Hatakenaka for helpful comments. This work was supported by the 21COE program on ‘‘Topological Science and Technology’’ from Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Technology of Japan. 2 2 c s Resistance vs. Temperature for Al-contacted TiSe2 flake, (a) −2 s DS • Electron beam lithography • Ohmic contact using Al (Tc ≈ 1.2K) • CDW transition confirmed • Device thickness = 20 nm ≈ 33 layers 2 4 LG d) • TiSe is a transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD), part of layered MX2 family (e.g. M = Ti, Mo, Nb, W, Ta. X = S, Se, Te). Quantum-Phase Electronics Center and Department of Applied Physics, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8656, Japan. 2Correlated Electron Research LGGroup, RIKEN, Hirosawa 2-1, Wako 351-0198, Japan. BG Resistance vs. Temperature for Nb-contacted TiSe2 flake, showing characteristic CDW peak at T ≈ 150K. The peak is suppressed possibly due to some local doping impurities contacts. fourby electrodes labeledorA,the B, C, and D shown with cross- c1 c) 14 DS c where superconductivity and CDW behaviour seem to coexist. The reason why superconductivity arises from the CDW state in TiSe2 on Cu doping has not yet been determined. It may be that Cu doping results in a tendency towards increasing the dimensionality of the Fermi surface, destabilizing the CDW and allowing for correlations to build in a third dimension, tipping the balance in favour of superconductivity. Otherwise, superconductivity may emerge from the CDW state due to the change in electron count on Cu doping. Further study of Cu 2 x TiSe2 will determine which of these c 1 c2 penetration depth, and ξ represents the coherence length), it can be concluded that Cu0.08 TiSe2 is in the extreme type-II limit, as κ ≈ 1 T/0.01 T = 100. The variation of the transport, magnetic and thermodynamic qualities of the normal state in the Cux TiSe2 series is summarized in Fig. 5. The resistivity, specific heat, magnetic susceptibility and Seebeck coefficient data taken together indicate that the Cu atoms contribute electrons to the conduction band on doping. This electron doping suppresses the CDW and induces metallic 1,2 13 2 c2 1,2 2 −2 B c 2 c c2 c 1 2 21/7/06, 4:43:44 pm −4 2 1 2 2 c c1 1 3 Goal: Investigate proximity induced superconductivity c 2 nature physics VOL 2 AUGUST 2006 www.nature.com/naturephysics Untitled-1 3 c1 Nano Letters ©2006 Nature Publishing Group x c • Nonlocal Josephson effect in Topological Insulator G (mS) different in these two approaches, owing to different signs of the Hall effect and an extreme sensitivity of pressure-induced superconductivity to magnetic compared to CuxTiSe TiSe . (a) Phase field diagram for Cu-doped 2. 2(b) Resistance versus • Max TThe Cu0.08TiSe2, ,and Figure 6 The Cu TiSe T–x electronic phase diagram. Open circles represent the c = 4.15K temperature for group several Cu-doping concentrations, ofand thethe transition metalshowing the parent compound–TiSe CDW transition temperature, filled circles correspond toIVb the superconducting 2 a representative evolution from toindicates superconducting state. Ref [1]. transition temperature. The shaded circleCDW at x = 0.04 that the transition Tc ≈ 2K for Pd TiSe to temperatures above 1.8 K: as the inset in Fig. 4a shows, the 0.11 2 diselenides, has been known since 1960s and has been extensively temperature is just below our minimum available temperature, andstudied the dashed circle due to the magnetization is linear in field at low H values; H is estimated at x = 0.06 marks the barely visible CDW transition at x = 0.06. Inset: Crystal as the field values where departures from linearity occurred at each unconventional nature of CDW state [11]-[24], for the first time examined in detail by Di Salvo . structure of Cu TiSe temperature. The anticipated linear temperature dependence close T is evident for both H and H (Fig. 4c), which also results [11]. At into room temperature, TiSe2 is either a semimetal [11]-[15],[24] or a semiconductor a linear √ thermodynamic critical field H (Fig. 4c), calculated as behaviour in Cu TiSe with a resistivity near 10 % cm at room temperature in the metallic phase. As the carriers are introduced, H = (H H ). [20],[22],[25] with a small indirect gap of the order contribution of 10-150 meVheat,[22],[25]. The possible γ , increases from to the specific Close to T = 0, BCS theory predicts that the upper critical field the electronic decreases with temperature as H (T ) ≈ H (0)[1 − 1.07(T /T ) ] approximately 1 to approximately 4 mJ mol K at the optimal reasons for ambiguous results beH(i) superconducting an insufficient resolution composition. Estimates ofof theARPES Wilson ratioexperiments, (ref.2these 27). The dashed line in Fig. 4c representscould a fit of the data to this expression, yielding a H (0) value of approximately R = χ /(3γ )(πk /µ ) (where χ is the temperature-independent (ii) a tiny1.39value of theT gap combined the strong CDW toisroom k is the fluctuations Boltzmann’s constant up and µ the Bohr temperature susceptibility, (3.2 K) estimated from thiswith fit is smaller T. (The zero-field than the measured value of 4.15 K, but the value of H (0) is magneton) based on the measured susceptibilities alone yield • well TiSe unique CDW to state with anexpected instability to a 2 Thedisplays [26] and (iii) a high sensitivitydataof(close theto crystal growing conditions R=1 T ) can also structure be values between defined.) high-temperature 0.3 and 0.4, much smaller than the [11]. used to estimate H , based on the equation H (0) = 0.693H (0) value for the free-electron approximation. The small susceptibilities superconducting yet less attention paid TiSe (ref. 28), where H (0in ) = −( dH /normal dT ) T . state, The phase dotted line in observed inof this system must be corrected for core to diamagnetism; TiSe the consists Ti layers sandwiched by octahedrally 2 compared 2 lattice Fig. 4c represents the extrapolation to T = 0 of the linear fit at however, correcting for the core contributions of Ti and Se (ref. 29) Se-Ti-Se. results in R valuesThe that seem to be too high configuration (between 2.5 high temperatures, yielding an estimate for H (a 0) = 1.27 T. On block coordinated Se atoms, thus creating trilayer described is the to other TMDs. the basis of these measurements, we conclude that the upper and 5). This suggests that additional contributions to the observed (0) = 1.33 ± 0.06 metal T. Despite dichalcogenides. susceptibility need to be considered to fully understand this system. field H (0) of Cu TiSe so-calledcritical 1T-polytype foris Htransition Quasi-two-dimensional crystal is left to a future study.devices based on TMDs the expected quadratic temperature dependence at low This analysis • exhibiting In general, superconducting proximity values the determined from field-dependent temperatures, the Hfrom Finally, the overall behaviour of this system is summarized in the trilayer structure magnetization, originates differences in the nature of chemical bonding within M(H ), measurements are probably overestimates the electronic phase diagram presented in Fig. 6. Using Cu doping have not been explored in detail. of the actual values. This could be a result of using polycrystalline as a finely parameter, CDW transition in TiSe blocks Se-Ti-Se (covalent bonding) and between the controlled blockstuning (van dertheWaals bonding). The latter pellets rather than single crystals, particularly if the critical field is is driven down in temperature, and a new superconducting state emerges. The superconducting state appears for x > 0.04, going anisotropic: the polycrystalline samples yield an average value H facilitatesthat the incorporation of foreign atoms into the van der Waals gap, being a wonderful tool is intermediate between the values corresponding to H ∥ ab through a maximum T of 4.15 K at x = 0.08, followed by a decrease and H ∥ c . Using the above critical field values to estimate the of T before the chemical phase boundary is reached at x = 0.11. for tuningGinzburg–Landau the electronic of(where compounds inisaa small controlled way [6]. boundary composition region (0.04 < x < 0.06) κ = l/ξ ≈ H /H l is the There parameterproperties 0 • Josephson effect in graphene SNS junctions I (nA) M/H (300 K) (e.m.u. per mol Ti) × 105 50 S (300 K) S (300 K) ( µV K–1) γ (mJ per mol Ti K2) ρ (300 K) /ρ (6 K) a) 40 ρ (300 K)/ρ (6 K) 5 0 T (K) SC CDW x = 0.01 x=0 We have fabricated field effect devices based on the layered dichalcogenide titanium diselenide (TiSe2). This material is a member of the transition metal dichalcogenides exhibiting a unique chiral charge density wave (CDW) state. This state has an onset at a temperature of T≈200K. Small amounts of copper or palladium dopants induce a superconducting state with superconducting critical temperature of Tc = 4.15K and 2K, respectively, which competes with the CDW state. By using field effect doping on single and few-unit-cell-thick layers we explore the interplay between superconducting and CDW states in proximity coupled superconducting devices. We have fabricated multi-terminal devices by mechanically exfoliating TiSe2 flakes from single crystals of TiSe2 onto SiO2 substrates, and defining Nb and Al contacts using optical and electron beam lithography techniques. We have confirmed that the CDW state persists in these devices when scaled to few-unit-cell thick layers. Future efforts include transport measurements of sub-micron devices down to milliKelvin temperatures. V Susceptibility (e.m.u. per Oe mol Ti) CuxTiSe2 H = 0.5 T V (µV) Interplay of Charge Density Wave and Superconducting States 3 × 10 – 5 pure TiSe2 at low temperatures show the presence of reflections corresponding to the basic trigonal structure and also the 2a,2c superstructure reflections associated with the CDW state3,19 . Figure 1b shows an electron diffraction pattern of Cu0.03 TiSe2 taken at approximately 120 K with the crystal tilted away from the [001] zone such that several higher-order Laue zones, with reflections hkl (l = −1, 0, 1 and 2) are visible. The superreflections are only observed for l = 2n + 1, and are not visible in the zeroorder Laue zone in the [001] orientation (where l = 0). The 2a,2c superstructure reflections, as indicated in the figure, are clearly seen, as they are in TiSe2 . Therefore, the charge density wave is still present at 120 K at this composition. Significantly, the characteristic CDW wavevector is unchanged by doping. Apart from the 2a,2c superstructure reflections, which are very sharp and only occur in the higher-order zones where l = 2n + 1, more-streaked reflections can be seen. Raising the temperature by approximately 20 K results in the disappearance of the 2a,2c superstructure reflections. The more-streaked reflections are still present above the CDW transition temperature and remain visible in diffraction patterns taken at room temperature. Furthermore, they are present in the diffraction pattern for Cu0.08 TiSe2 , the optimal superconducting composition, at 120 K (Fig. 1c) and also in pure TiSe2 at room temperature. The positions of these diffuse peaks are only in part the same as those of the 2a,2c superstructure, as shown in the overlays. The diffuse superreflections are not confined to a small band at l = 2n + 1 but are present everywhere, indicating that they are also streaked along c ∗ (perpendicular to the TiSe2 planes): the streaking seems to be continuous in that direction. It would be of interest to characterize the diffuse scattering as a function of temperature and composition and determine its origin. It is probably associated with the soft phonon believed to accompany the CDW transition25 . Figure 2a shows the temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibilities for Cux TiSe2 over the range of Cu solubility. The normal-state susceptibility (for example, at 300 K) increases with Cu content. This suggests that the Cu doping introduces carriers into the conduction band in TiSe2 , increasing the electronic density of states and therefore the Pauli paramagnetism. This is further confirmed by specific heat measurements, described below. A drop in the susceptibility of pure TiSe2 is seen as the temperature is lowered below the CDW transition at 200 K, consistent with the decrease in electronic density of states that occurs on opening a gap at the Fermi level (the susceptibility becomes negative because the core diamagnetism is larger than the Pauli contribution). On doping with increasing amounts of Cu, the CDW state in Cux TiSe2 exists until x = 0.06, as seen in the drops in the susceptibilities. The susceptibility drop decreases with increasing Cu content, implying that fewer states are gapped at the CDW transition. The CDW transition temperatures can be determined from the onsets of the susceptibility drops, and decrease continuously with increasing Cu content. For x = 0.06, the CDW transition, marked by a very small change in susceptibility, is reduced below 60 K and is no longer visible for higher x . The fact that local moment magnetism is not generated by Cu doping indicates that the intercalated Cu has a formal oxidation state of +1, a 3d 10 electron configuration. A systematic change in the transport properties of Cux TiSe2 occurs on increasing x . The resistivity of our pure TiSe2 (Fig. 2b) is very similar to that previously reported3 : a broad maximum occurs around 150 K, with the ratio ρ(150 K)/ρ(300 K) = 4, comparable to that of the stoichiometric crystals3 . However, unlike the single crystals where the ratio ρ(300 K)/ρ(6 K) is 3–4, in our sample this ratio is smaller than unity, probably due to the fact that it is a polycrystalline pellet. As shown in Fig. 2b, the resistivity maximum in Cux TiSe2 associated with the CDW state broadens and moves towards lower temperatures with increasing Cu doping, dV/dI (kΩ) 4 × 10 – 5 R (kΩ) a I (nA) Background & Motivation Bipolar supercurrent in graphene V (µV) James 2 Curtis , I (nA) 1Department Sam 1 Ciocys , G (4e2/h) Joseph G. 1 Lambert , ■ ■ Conclusions & Future Work ■ • We have fabricated sub-micron TiSe2 devices with good Ohmic contact electrodes,to using superconductors a Ti/Al (5 nm/350 nm thick and 400 nmAl and Nb, using electron beam and optical wide) bilayer in place of the Ti/Au bilayer. The thin Ti layers were addedlithography. to create a good ohmic contact at the BSTS/Al and BSTS/Au interfaces. The electrical leads A and B (C and D ) Fig. 2. Transport properties of the thin-flake MoS2 EDLT. (A) Temperature dependence of the channel sheet resistance Rs at different VLG gate biases ranging from 0 to 6 V (indicated on the right). (B) Temperature dependence of the channel sheet resistance Rs at VLG = 1 V and different VBG’s showing a metal-insulator transition at n2D = 6.7 × 1012 cm−2. For each VBG, we marked 1 1 1 1 the corresponding n2D measured by the Hall effect at 20 K. (C) Phase diawere the source and drain for current biasing the Al−BSTS−Al gram showing the evolution of different electronic phases as a function of carrier density n2D. The phase diagram shows an insulating (n2D < 6.7 × (Au-BSTS-Au) junction by IA1B1 (IC1D1), while the potential 1012 cm−2), a metallic (6.7 × 1012 < n2D < 6.8 × 1013 cm−2), and a domesuperconducting phase (n2D > 6.8 × 1013 cm−2), where the color corusing difference VA2B2 (VC2D2) across the junction was measured like 5030 responds to the logarithm of the sheet resistance Rs (W). (D) Normalized 5033 | Nano for Lett.dif2014, 14, 5029−5034 superconducting transition Rs/Rs (15K)dx.doi.org/10.1021/nl501481b as a function of temperature ferent gate voltages. The Tc is marked as a circle at 90% of the total transition. Both VLG and VBG are varied; for a given VLG, we show the evolution of the transition with increasing VBG. All data corresponding to the same VLG are shown with the same color. The dashed arrows indicate the order of increasing VBG from –4 to 2 V in ∆VBG = 2 V. (Upper panel) For VLG between 4 and 5.5 V, Tc increased with increasing VBG; (bottom panel) for VLG SD = 6 V, Tc decreased with increasing VBG because the corresponding n2D had reached the peak of the superconducting dome. Figure 2. Four-probe transport properties recorded at VG current I . The observed temperature dependence of t superconducting transition at lower T (b). The inset of dependence of the square resistance for different values of www.sciencemag.org which makes it possible to determine T more precisely. E C function of B for T = 0.25 K (e). (f) Two-dimensional • Charge density wave transition observed in both types of devices. dx.doi.org/10.1021/nl501481b | Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5029−5034 1194 30 NOVEMBER 2012 VOL 338 SCIENCE • Millikelvin electronic transport experiments are ongoing. Upon further cooling we see that below approximat the device exhibits a sharp, large decrease of resista 2b zooms-in on the behavior of R□(T) below T = 10 it apparent that at T ≃ 4 K, the device starts un transition to a zero resistance state, which is attained 0.4 K. This is the first observation of a superconduc WS2. It demonstrates that the possibility of elec inducing superconductivity in semiconducting TM confined to Mo-based compounds27−29 (the only on the phenomenon had been reported 2 so far). To further substantiate that the zero-resistance manifestation of superconductivity, we investigated the presence of an applied perpendicular magnetic magnetoresistance measured at T = 0.25 K is shown of Figure 2b. We find that a truly zero-resistance s only up to B = 10 G, and that at higher value resistance increases rapidly, reaching the value meas • This work is sponsored by the US Army Research Office under contract normal state at B = 0.14 T (i.e., the critical field at T W911NF-14-1-0567 BC = 0.14 T). For large field values the magnetor essentially negligible. Figure 2c further shows the e • Fabrication facilities provided by: R□ as a function of T, in the presence of differen applied perpendicular field, which confirms h • Dr. Xiaoxing Xi, Physics Dept., Temple University conductivity is suppressed on a magnetic field sc • Dr. Chris Lobb, CNAM and Physics Dept., University of Maryland 0.1 T. The same data show that above 4 K virtually of resistance with magnetic field is observed, confi • Future experiments include: • Use superconducting and normal contacts to investigate nonlocal superconducting transport properties. • Measure device characteristics down to single and few layer TiSe . Acknowledgements