Document 11124727

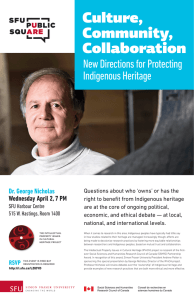

advertisement