SHADOWS OF THINGS PAST AND IMAGES OF THE FUTURE: Max G. Manwaring

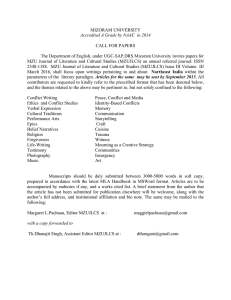

advertisement