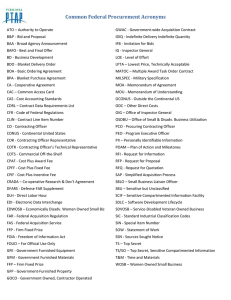

Acquisition

advertisement