Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

advertisement

Revista Colombiana de Estadística

Junio 2008, volumen 31, no. 1, pp. 95 a 109

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated

Secondary Variables

Análisis de covarianzas con variables secundarias correlacionadas

espacialmente

Tisha Hooks1,a , David Marx2,b , Stephen Kachman2,c ,

Jeffrey Pedersen3,d , Roger Eigenberg3,e

1 Department

of Mathematics and Statistics, Winona State University, Winona,

United States

2 Department

3 Department

of Statistics, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, United States

of Agronomy and Horticulture, USDA-ARS Research, University of

Nebraska, Lincoln, United States

4 USDA-ARS

U.S. Meat Animal Research Center, Clay Center, United States

Abstract

Advances in precision agriculture allow researchers to capture data more

frequently and in more detail. For example, it is typical to collect “on-the-go”

data such as soil electrical conductivity readings. This creates the opportunity to use these measurements as covariates for the primary response

variable to possibly increase experimental precision. Moreover, these measurements are also spatially referenced to one another, creating the need for

methods in which spatial locations play an explicit role in the analysis of

the data. Data sets which contain measurements on a spatially referenced

response and covariate are analyzed using either cokriging or spatial analysis of covariance. While cokriging accounts for the correlation structure of

the covariate, it is purely a predictive tool. Alternatively, spatial analysis

of covariance allows for parameter estimation yet disregards the correlation

structure of the covariate. A method is proposed which both accounts for

the correlation in and between the response and covariate and allows for

the estimation of model parameters; also, this method allows for analysis of

covariance when the response and covariate are not colocated.

Key words: Covariance Analysis, Spatial Analysis, Cokriging, Covariate.

a Assistant

Professor. E-mail: THooks@winona.edu

E-mail: DMarx1@unl.edu

c Professors. E-mail: SKachman1@unl.edu

d Geneticist and Professor. E-mail: JPedersen1@unl.edu

e Researcher. E-mail: REigenberg2@unl.edu

b Professors.

95

96

Tisha Hooks, et al.

Resumen

Los avances en agricultura de precisión permiten a los investigadores

obtener datos con más frecuencia y en detalle. Por ejemplo, es común colectar “en el transcurso” datos como lecturas de electro-conductividad del suelo.

Esto crea la oportunidad de usar estas medidas como covariables para incrementar la precisión experimental de la variable de respuesta. Aún más,

estas medidas están espacialmente relacionadas entre sí, creando la necesidad

de métodos en los cuales la ubicación espacial representa un papel explícito

en el análisis de los datos. Se analizan conjuntos de datos que contienen

variables de respuesta y covariables espacialmente relacionadas, usando el

método cokriging o el análisis espacial de covarianza. Aunque el método cokriging usa la estructura de correlación de la covariable, es una herramienta

puramente predictiva. Alternativamente, el análisis espacial de covarianza

permite la estimación de parámetros pero sin tener en cuenta la estructura

de correlación de la covariable. El presente artículo propone un método que

tiene en cuenta la correlación en la covariable, así como la correlación entre

la covariable y la variable de respuesta, permitiendo la estimación de los

parámetros del modelo. De la misma manera, este método permite el análisis espacial de covarianza cuando la variable de respuesta y la covariable no

están colocalizadas.

Palabras clave: análisis de covarianzas, covarianza espacial, cokriging, covarianza.

1. Introduction

With recent advances in precision agriculture, researchers are now able to capture data more frequently and in more detail. For example, it is typical to collect

“on-the-go" data such as soil electrical conductivity readings. This creates the

opportunity to use these measurements as covariates for the primary response variable to possibly increase experimental precision. Moreover, these measurements

are also spatially referenced to one another, creating the need for methods in which

spatial locations play an explicit role in the analysis of the data. These covariates

are usually measured before the treatment is applied and hence the assumption

that the covariate is not affected by the treatment is met.

A standard framework for the analysis of spatial data considers a response

variable, Y (s), which is in principle obtainable at any location, s, within a twodimensional spatial region R. Let these spatial locations be indexed by site si .

Data values ysi = yi are obtained from locations si , i = 1, 2, . . . , n, and are

assumed to follow the model

Y (si ) = µ(si ) + e(si ),

i = 1, 2, . . . , n

where Y (si ) = Yi is the response variable, µ(si ) is the deterministic trend, and

e(si ) is a stochastic error term with some spatial covariance structure (Dubin

1988). Applications of this model fall into two broad categories: spatial prediction

problems and estimation problems. In spatial prediction problems, the objective

is to predict the value of the response variable at some arbitrary location, s0 ,

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

97

given the data y = (y1 , y2 , . . . , yn ). In estimation problems, interest centers on

estimating model parameters such as treatment effects. A thorough discussion of

methods applicable to these types of problems can be found in texts such as Journel

& Huijbregts (1978), Isaaks & Srivastava (1989), Cressie (1993), and Goovaerts

(1997).

Often, data collected on the response variable are supplemented by additional

information collected on the covariates. The model given above can be extended to

include the covariates. In spatial prediction problems, the joint data are analyzed

using the cokriging approach (Goovaerts 1997). In this case, the model can be

expressed as

Y1 (s1i ) = µ1 (s1i ) + e1 (s1i ),

i = 1, 2, . . . , n1

Y2 (s2i ) = µ2 (s2i ) + e2 (s2i ),

i = 1, 2, . . . , n2

where Y1 (s1i ) is the response variable, Y2 (s2i ) is the covariate, µ1 (s1i ) and µ2 (s2i )

represent deterministic trend, and e1 (s1i ) and e2 (s2i ) are random error terms with

some spatial covariance structure. This approach is most advantageous when Y2

is more densely sampled than the response variable. Cokriging explicitly accounts

for spatial cross-correlation between the response and secondary variable in that

e1 (s1i ) and e2 (s2i ) have a spatial correlation structure and a cross-correlation between them. Incorporated into the procedure is the usual restriction that the covariance matrix associated with the cross-covariogram be positive definite (Isaaks

& Srivastava 1989). Ordinary cokriging then predicts Y1 (s0 ) using information

from the data Y1 (s1i ) and the covariate Y2 (s2i ). Universal cokriging allows for a

trend or large scale structure in the prediction equations under the assumption of

coregionalization. However, in order for the covariate to have any influence on the

estimation of the large scale structure parameters, a restriction on the parameter space that jointly involve parameters in the response and covariate variables

must be made (Helterbrand & Cressie 1994). Making such a restriction, such as

assuming the mean of the response variable and covariate are equal, it is often too

restrictive to make universal cokriging of any practical use for estimation. Universal cokriging can also be used as a regression procedure (Stein & Corsten 1991).

While the cokriging approach is an extremely useful geostatistical tool, it is used

only in prediction problems and does not easily allow for the estimation of treatment effects.

In spatial estimation problems where interest centers on estimating model

parameters or testing for treatment differences, data consisting of measurements

on a response variable and a covariate are usually analyzed using a spatial analysis

of covariance. Analysis of covariance methods use information about the response

variable that is contained in another variable in order to improve estimation, and

a detailed description of this tool can be found in Searle (1971) and Milliken &

Johnson (2002). The basic analysis of covariance model is as follows:

yij = αi + βi xij + eij

where i = 1, 2, . . . , t, j = 1, 2, . . . , ni , the mean of yi for a given value of X is αi +

βi X and eij ∼ i.i.d. N (0, σ 2 ). Note that this model has t intercepts and t slopes

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

98

Tisha Hooks, et al.

and thus represents a collection of simple linear regression models with a different

model for each level of the treatment. If equal slopes are assumed, the model used

to describe the mean of y as a function of the covariate is

yij = αi + βxij + eij

where eij ∼ i.i.d. N (0, σ 2 ) (Milliken & Johnson 2002).

If the assumption on the error term is relaxed and eij is alternatively assumed

to have some spatial covariance structure, the model becomes a spatial analysis

of covariance model (Cressie 1993, Zimmerman & Harville 1991). In this case,

the analysis uses information from both the response variable and the covariate

in order to obtain more accurate parameter estimates. Dubin (1988) proposed

this approach for spatially autocorrelated error terms. However, this method accounts for only the spatial correlation that exists in the response variable. If the

covariate has a spatial correlation structure and a cross-correlation with the response variable, the analysis does not take these spatial correlation structures into

account.

Consider the case where the primary attribute of interest (response variable)

and a secondary variable (covariate) possess some spatial structure, and assume interest lies in estimating treatment effects. For example, consider the situation and

an agronomic trial is conducted where the field fertility contains spatial structure.

The experimental design of the study can be any appropriate classical design, but

the appropriate analysis will include a spatial component (Marx & Stroup 1993).

If soil testing of the area has been conducted recently, then the soil fertility can

be more accurately estimated using these measurements. There will generally be

fewer soil sample locations than plots and these will not be colocated with the

centers of the plots. A hypothetical schematic is given in Figure 1, where there

is a 6 × 6 arrangement of plots with 20 gridded soil sample locations throughout

the field. In another example, a recent study conducted at the U.S. Meat Animal

Research Center in Clay Center, Nebraska, compared a cover crop treatment and

a no-cover crop treatment for values of ammonia nitrogen. Also, soil electrical

conductivity readings were used as a covariate. In this situation, the response

variable and a covariate possessed a spatial structure. These spatial correlations

and the cross-correlation structure that exists between them need to be included

in the analysis as it is in the cokriging approach, but parameter effects need to

be estimated as in spatial analysis of covariance. The objective of this work is

to develop a model that accounts for the correlation in and between the response

and covariate and allows for the estimation of model parameters. In the following pages, the proposed model and methodology are described, the analysis of a

simulated data set in which the response and covariate are colocated is presented

(colocated data occur when the response variable and the covariate are measured

at the same geographic coordinates), the methodology is applied to a simulated

data set in which the data are not colocated; and the methodology is used to

analyze a soils data set obtained from the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center.

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

99

Figure 1: Hypothetical agronomic field trial where additional information is available

through soil test samples.

2. Model and Methods

For colocated data, the model can be expressed as

y = Xτ + βu + ey

(1)

u = 1µ + eu

where y is an n × 1 vector containing the measurements of the observed y(si )’s at

sites in Syu , u is an n × 1 vector containing the covariate observations u(si )’s at

sites in Syu , X is an n × p design matrix for treatment effects, τ is a p × 1 vector

of treatment effects, β is the regression coefficient for the covariate, 1 is an n × 1

vector of 1’s, and µ represents the mean of the covariate. Also, the model assumes

ey ∼ N (0, σy2 R)

and

eu ∼ N (0, σu2 R)

where R represents a spatial correlation structure (e.g., spherical, gaussian, or

exponential)(Cressie 1993). It can be seen that

E(y) = E(Xτ + βu + ey ) = Xτ + βE(u) = Xτ + β1µ

E(u) = E(1µ + eu ) = E(1µ) = 1µ

Also, since the term βu in equation (1) can contain any correlation between y

and u, it can be assumed that Cov(ey , eu ) = 0. Then,

V ar(y) = V ar(Xτ + βu + ey ) = β 2 V ar(u) + V ar(ey ) = β 2 V ar(eu ) + V ar(ey )

V ar(u) = V ar(1µ + eu ) = V ar(eu )

Cov(y, u) = Cov(Xτ + βu + ey , 1µ + eu ) = Cov(Xτ + β(1µ + eu ) + ey , 1µ + eu )

= Cov(βeu + ey , eu ) = Cov(βeu , eu ) + Cov(ey , eu ) = βV ar(eu )

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

100

Tisha Hooks, et al.

Finally, the model assumptions can be written as

y

∼N

u

Σ

Xτ + β1µ

, yy

Σuy

1µ

Σyu

Σuu

!

where

Σyy = β 2 Σuu + Σyy = (β 2 σu2 + σy2 )R

Σuu = V ar(eu ) = σu2 R

Σyu = βΣuu = βσu2 R

thus,

y

∼N

u

2 2

(β σu + σy2 )R

Xτ + β1µ

,

βσu2 R

1µ

!

βσu2 R

σu2 R

(2)

For the univariate case, the variance of the response variable is defined as

κ2y = V ar(yi ) = β 2 σu2 + σy2

(3)

and the variance for the covariate is defined as

κ2u = V ar(ui ) = σu2

(4)

κyu = Cov(yi , ui ) = βσu2

(5)

Also,

Let ρ represent the correlation between the covariate and response variable.

The relationship between ρ and β can be described as follows:

κyu

κyu

= 2

σu2

κu

Cov(yi , ui )

κyu

=⇒ κyu = ρκy κu

ρ= p

=

κy κu

V ar(yi )V ar(ui )

κyu = βσu2 =⇒ β =

thus,

ρκy κu

ρκy

=

2

κu

κu

ρ̂κˆy

β̂ =

κˆu

β=

(6)

Note that κy is also the square root of the sill for the response and κu is the

square root of the sill for the covariate. The covariance matrix in (2) can easily be

reparameterized to have just one error term. Since, in our situation, we have two

variables, we chose to have two error terms rather than just one and the other error

term then being a proportionality constant times the first error term. This is in

agreement with Oliver (2003) (equations (3), (4), and (5)). Additionally note that

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

101

Oliver constructs the cosimulation by using independent Gaussian random variables which again implies that the assumption of zero covariance is made without

loss of generality.

This model notation can be extended to non-colocated data (Banerjee

et al.

S

2004). Let y be the vector of observed y(si )’s at S

the sites in Syu Sy and u be

the vector of observed u(sj )’s at the sites in Syu Su . Let y ′ denote the vector

of missing y observations in Su and u′ denote the vector of missing u observations

in Sy . Then, the vectors for the response and covariate observations from the

previous discussion can be replaced with the augmented vectors yaug = (y, y ′ ) and

uaug = (u, u′ ). After permutation to line up the y’s and u’s, they can be collected

y

yaug

of equation (2).

which is analogous to the vector

into a vector

uaug

u

A program which models the covariance structure in equation (2) was written in

R (R Development Core Team 2004). The program uses generalized least squares

and yields restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimates of the range, the

sills for the response variable and for the covariate, treatment effects, and the

correlation between the response and the covariate. Also, the results give the F value for testing for an overall difference in treatment effects, and an approximate

z-test is constructed using the asymptotic variance of ρ to test whether or not ρ

(and equivalently β) is significantly different from zero. The denominator degrees

of freedom for the F -test can be found by subtracting the number of fixed effects

from the number of observations on the response variable. Finally, an estimate for

β can be found using the relationship between β and ρ given in equation (6). The

program, simulated data sets, and soils data set may all be obtained from the first

author.

3. Example Using Simulated Colocated Data

The simulated data set consisted of 20 replications of five treatments. The

treatments were laid out in a completely randomized design on a 10 × 10 arrangement of plots. For each of the 100 points, both a spatial floor (Y ) and a

spatial covariate (X) were generated using the method of gaussian cosimulation

(Oliver 2003).

In this example, the spherical covariance function was used for the construction

of both variables. The function is as follows:

(

σ 2 {1 − 32 ( ha ) + 12 ( ha )3 }, if 0 ≤ h ≤ a;

C(h) =

0,

if h > a.

where h is the distance between observations, a is the range of the corresponding

spherical semivariogram, and σ 2 is the sill of the semivariogram. The response

variable was simulated with a range of 8 and a sill of 10, and the covariate was

simulated with a range of 8 and a sill of 1. Two different correlations of ρ = 0.3

and 0.8 were simulated when modeling the cross-covariance between the spatial

floor and the covariate. Finally, the mean of both the response variable and the

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

102

Tisha Hooks, et al.

covariate was simulated to be 10, and treatment effects were generated with the

treatment vector τ = (−0.4, −0.2, 0, 0.2, 0.4).

The data were analyzed in three ways: using a nonspatial analysis of covariance, a spatial analysis of covariance, and the proposed analysis which accounts

for the spatial structure of both the response and the covariate. The results are

summarized in Tables 1-3. The spatial analyses yield more accurate estimates

than the analysis which disregards the location of the observations. As displayed

in Tables 1 and 2, the estimate for β is much closer to the simulated value and

the average standard error of treatment differences is much smaller for the spatial

analyses. Also, the estimates for σy2 and for the regression coefficient for the

covariate are very close for the proposed method and spatial analysis of covariance. While the proposed method provides the most accurate representation of the

treatment effects as seen in Table 2, it is observed that the average standard error

of treatment differences is very close to that obtained from a spatial analysis of

covariance. Table 3 shows the results of hypothesis tests for treatment differences

and significance of the covariate for all three analyses. Overall, the results from the

proposed method are very close to the results obtained from the spatial analysis

of covariance, and it appears that little is gained when accounting for the spatial

structure of the covariate when the response and covariate are colocated. The same

results occur for ρ = 0.3 as seen in Table 4. In addition to the proposed method

giving a slightly smaller average standard error of treatment differences, the least

square means were slightly closer to the simulated data means (not shown). Thus,

one may choose to use a simple spatial analysis of covariance to test for treatment

differences since the precision that is gained via use of the proposed method may

not be worth the extra effort that is required.

Table 1: Parameter estimates from the three analyses conducted in the example using

simulated colocated data with ρ = 0.8.

Parameter of

Interest

Range

sill for response

sill for covariate

β

Analysis of

Covariance

–

–

–

3.37

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

8.74

4.31∗

–

2.33

Proposed

Method

8.61

9.73

1.02

2.33

Simulated

Data

8.00

10.00

1.00

2.53

∗ Note that 4.31 actually represents σ̂ 2 , whereas the sill for the response is κ2 .

y

y

For the proposed method, σ̂y2 is calculated to be 4.20 using equation (3). The

simulated σy2 is 3.60.

However, this is not to imply that the proposed method is not extremely useful.

The true strength of this analysis is more than simply accounting for the spatial

structure of the covariate. Its power lies in the fact that this model allows for

covariate measurements that are not colocated with measurements of the primary

attribute of interest. An example which considers a data set in which the covariate

is measured at locations different from the response variable is presented in the

next section.

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

103

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

Table 2: Least squares means for treatments and average standard errors of treatment

differences from the three analyses conducted in the example using simulated

colocated data with ρ = 0.8.

LSMEAN for

treatment 1

LSMEAN for

treatment 2

LSMEAN for

treatment 3

LSMEAN for

treatment 4

LSMEAN for

treatment 5

Average standard

error of treatment

differences

Analysis of

Covariance

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

Proposed

Method

Simulated

Data

10.860

10.150

9.980

9.6

10.670

10.290

10.110

9.8

10.930

10.460

10.280

10.0

11.580

10.780

10.610

10.2

11.560

10.720

10.540

10.4

0.478

0.260

0.255

–

Table 3: Results of hypothesis tests for treatment differences and significance of the

covariate from the three analyses conducted in the example using simulated

colocated data with ρ = 0.8.

test for treatment

differences

test for significance

of covariate

Analysis of

Covariance

F = 1.54

(p -value = 0.1976)

F = 327.90

(p -value < 0.0001)

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

F = 1.75

(p -value = 0.1448)

F = 119.57

(p -value < 0.0001)

Proposed

Method

F = 1.20

(p -value = 0.3174)

z = 3.668

(p -value < 0.0001)

Table 4: Parameter estimates from the three analyses conducted in the example using

simulated colocated data with ρ = 0.3.

Parameter of

Interest

Range

sill for response

sill for covariate

β

Average standard

error of treatment

differences

Analysis of

Covariance

–

–

–

1.220

0.778

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

7.220

6.320∗

–

0.800

0.333

Proposed

Method

10.05

9.40

0.90

0.83

0.328

Simulated

Data

8.00

10.00

1.00

0.95

–

∗ Note that 6.32 actually represents σ

by2 whereas the sill for the response is κ2y .

4. Example Using Simulated Non-Colocated Data

The simulated experiment consisted of twenty replications of five treatments.

The treatments were laid out in a completely randomized design on a 10 × 10 arrangement of plots. Within each plot, another 3×3 grid of points was constructed.

For each of the 900 points, a spatial floor (Y ) and a spatial covariate (X) were

generated using the method of gaussian cosimulation (Oliver 2003).

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

104

Tisha Hooks, et al.

The spherical covariance function was used for the construction of both variables. The response variable was simulated with a range of 25 and a sill of 5,

and the covariate was simulated with a range of 25 and a sill of 1. Correlations

of ρ = 0.8 and 0.3 were simulated when modeling the cross-covariance between

the spatial floor and the covariate. Finally, the mean of the response variable

and the covariate was simulated to be 10, and treatment effects were generated

with the treatment vector τ = (−0.5, −0.25, 0, 0.25, 0.5). These treatment effects

correspond to treatments A, B, C, D, and E, respectively.

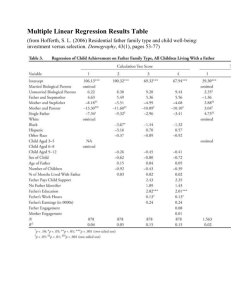

The final data set was constructed as follows. First, the center observation

from each of the 100 plots was used as the response variable. Then, 25 of the 100

remaining responses were randomly chosen and deleted from the data set. Finally,

90% of the 900 covariate observations were randomly selected and deleted. A

representation of this simulated data set is given in Figure 2. For each plot, the

treatment (A, B, C, D, or E) is identified, and the black squares represent the

location of the sampled covariates. Clearly, the response and the covariate are

not colocated in this example, and there are more covariate observations than

measurements on the response.

Figure 2: Simulated data set in which the response and covariate are not colocated.

Treatments A-E for each plot and the locations of the sampled covariates are

identified.

The data were first analyzed using the proposed analysis which accounts for the

spatial structure of both the response and the covariate. In order to compare this

to a spatial analysis of covariance, a data set in which the response and covariate

were colocated was constructed by using the covariate measurement which was

closest to the central observation of each plot as the covariate for that plot. If

two covariate measurements were equally distant from the center of the plot, the

covariate was calculated as their average. A spatial analysis of covariance was then

conducted using this data set. The results from both analyses are summarized in

Tables 5-7.

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

105

Table 5: Parameter estimates from the three analyses conducted in the example using

simulated colocated data with ρ = 0.8.

Parameter of

Interest

Range

sill for response

sill for covariate

β

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

27.43

4.75∗

–

0.83

Proposed

Method

27.35

5.16

1.02

2.02

Simulated

Data

25.00

5.00

1.00

1.79

∗ Note that 4.75 actually represents σ

by2 , whereas the sill for the res-

ponse is κ2y . The simulated σy2 is calculated to be 1.80 using

equation (3).

Table 6: Least squares means for treatments and average standard errors of treatment

differences from the three analyses conducted in the example using simulated

colocated data with ρ = 0.8.

LSMEAN for

treatment 1

LSMEAN for

treatment 2

LSMEAN for

treatment 3

LSMEAN for

treatment 4

LSMEAN for

treatment 5

Average standard

error of treatment

differences

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

Proposed

Method

Simulated

Data

10.000

9.540

9.50

9.930

9.360

9.75

10.460

10.200

10.00

10.560

10.340

10.25

10.680

10.270

10.50

0.304

0.241

–

Table 7: Results of hypothesis tests for treatment differences and significance of the

covariate from the three analyses conducted in the example using simulated

colocated data with ρ = 0.8.

Test for treatment

differences

Test for significance

of covariate

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

F = 2.10

(p -value = 0.0909)

F = 10.21

(p -value = 0.0021)

Proposed

Method

F = 6.06

(p -value = 0.0003)

z = 1.9580

(p -value = 0.0502)

As seen in Table 5, the proposed analysis yields a much more accurate estimate

of β than the spatial analysis of covariance. Moreover, the estimate of the sill

for the response variable (κ2y ) from the proposed analysis is very close to the

simulated value, but the estimate of σy2 from the spatial analysis of covariance is

considerably different from the simulated value. Also, as illustrated in Table 6, the

proposed method provides more accurate representations of most of the treatment

effects, and the average standard error of treatment differences provides a 20%

improvement over the average standard error of treatment differences from the

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

106

Tisha Hooks, et al.

Table 8: Parameter estimates from the three analyses conducted in the example using

simulated colocated data with ρ = 0.3.

Parameter of

Interest

Range

sill for response

sill for covariate

β

Average standard

error of treatment

differences

Spatial Analysis

of Covariance

20.520

4.200∗

–

0.100

Proposed

Method

20.330

5.120

0.760

0.520

0.335

0.329

Simulated

Data

25.00

5.00

1.00

0.67

–

∗ Note that 4.20 actually represents σ

by2 whereas the sill for the

response is κ2y .

spatial analysis of covariance. The F -statistic is larger for the proposed analysis

(Table 7), but there is no reason to expect that the F -statistics be comparable

since the proposed method uses all covariate points and the spatial analysis of

covariance uses a subset of the covariates. Moreover, some covariate points are used

twice in the spatial analysis of covariance. A relatively large correlation between

the response variable and covariate was chosen so that the analysis of covariance

would be very effective. To see if the results held for a smaller correlation, a

correlation of ρ = 0.3 was simulated using the same parameters (range, sill for

response and covariate, treatment means) as were used for the ρ = 0.8 simulation.

These results, shown in Table 8, indicate that the same trend as seen for ρ = 0.8

continue, but with a lesser effect. The average standard error of the treatment

differences was reduced slightly using the proposed method compared to spatial

analysis of covariance and the least square means were slightly closer to the simulated means using the proposed method (data not shown). Our conclusion is

that the stronger the association between the response variable and covariate the

greater the improvement by using the proposed method. The true strength of the

proposed method is that even the spatial analysis of covariance should not be run

except when the data are colocated. Our proposed method is the only procedure

which allows for non-colocated data and tests of treatment effects.

5. Example Using Actual Field Data

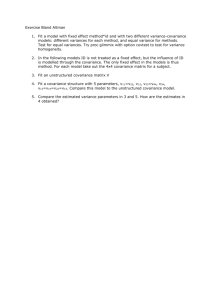

These data were obtained from a study site located at the U.S. Meat Animal

Research Center located in Clay Center, Nebraska. The site was treated with four

replications of a winter wheat cover crop versus four replications of a no-cover

crop. The treatments were laid out in a randomized complete block design with

subsampling. The response variable consisted of ammonia nitrogen levels obtained

from soil cores. Also, soil electrical conductivity measurements taken prior to

treatment application were used as a covariate, and the geographical coordinates

(northing and easting) were recorded at each measured location. A representation

of this data set is given in Figure 3.

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

107

Figure 3: Soils data set in which the response and covariate are not colocated. Locations where soil cores were taken for the response are marked by diamonds,

and locations of the sampled covariates are also identified.

The proposed method was used for the analysis since the response variable and

covariate are not colocated. The data were analyzed as a randomized complete

block design with subsampling and fixed block effects. A spherical covariance

structure was assumed, and the results are summarized in Tables 8-10.

All parameter estimates in Table 9 are reasonable. Table 10 shows the least

squares means of the two treatments and the standard error of their difference.

Finally, as shown in Table 11, there does not appear to be a difference in values

of ammonia nitrogen for cover crop treatment versus a no-cover crop treatment.

Moreover, the covariate (soil electrical conductivity) is not significant.

Table 9: Parameter estimates from the soils data example.

Parameter of

Interest

Range

sill for response

sill for covariate

β

Estimate from

Proposed Method

12.0600

0.9800

43.5100

−0.0350

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

108

Tisha Hooks, et al.

Table 10: Least squares means for treatments and average standard errors of treatment

differences from the analysis of the soils data.

Estimate from

Proposed Method

LSMEAN for

treatment 1

LSMEAN for

treatment 2

Standard error of

treatment difference

3.9900

3.8800

0.2032

Table 11: Results of hypothesis tests for treatment differences and significance of the

covariate from the analysis conducted in the soils data example.

Test for treatment

differences

Test for significance

of covariate

F = 0.55

(p -value = 0.5125)

z = −0.75

(p -value = 0.4532)

6. Discussion and Conclusion

First of all, it should be noted that the proposed method and analysis make

the usual intrinsic coregionalization assumption of equal ranges for the response

variable and the covariate. The model could be altered to allow for this assumption

to be relaxed, but the current framework assumes the correlation matrices are

proportional to each other.

Also, the results from the proposed method and the spatial analysis of covariance are very similar when the data are colocated. It appears that little is gained

by accounting for the correlation structure of the covariate, and if the response

variable and the covariate are colocated, the authors recommend analyzing the

data using a simple spatial analysis of covariance. In fact, when data are colocated,

the results are a generalized form of the error-in-variables problem. However, the

true power of this analysis lies in the fact that the model allows for analysis of

covariance when data are not colocated. Using this method, it is not essential that

the covariate and response be measured at the same location or to have the same

number of observations for the response and covariate. Although a data set in

which the response and covariate are not colocated can be manipulated so that a

spatial analysis of covariance is appropriate, more than one choice for a covariate

exists. For example, the covariate could have been constructed by averaging all

covariate measurements within a plot, had the data allowed for this. The construction of the covariate is arbitrary and has not statistical validation associated with

it; thus, using the proposed method is superior to the alternative. The spatial

locations of the covariates play a role in the proposed analysis, and this leads

to more precision in testing for treatment differences. Lastly, and perhaps most

importantly, experiments where the covariate is available at fewer locations than

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109

109

Analysis of Covariance with Spatially Correlated Secondary Variables

the primary variable still allows this supplementary information to be incorporated

into the analysis.

Recibido: noviembre de 2007 — Aceptado: mayo de 2008

ˆ

˜

References

Banerjee, S., Carlin, B. P. & Gelfand, A. E. (2004), Hierarchical Modeling and

Analysis for Spatial Data, Chapman and Hall/CRC Press.

Cressie, N. A. C. (1993), Statistics for Spatial Data, John Wiley and Sons, Inc.,

New York, United States.

Dubin, R. (1988), ‘Spatial Autocorrelation’, Review of Economics and Statistics

70(466-474).

Goovaerts, P. (1997), Geostatistics for Natural Resources Evaluation, Oxford University Press, New York, United States.

Helterbrand, J. D. & Cressie, N. (1994), ‘Universal Cokriging Under Intrinsic

Coregionalization’, Mathematical Geology 26(2), 205–226.

Isaaks, E. H. & Srivastava, R. M. (1989), An Introduction to Applied Geostatistics,

Oxford University Press, New York, United States.

Journel, A. G. & Huijbregts, C. J. (1978), Mining Geostatistics, Academic Press,

New York, United States.

Marx, D. & Stroup, W. (1993), Analysis of Spatial Variability using PROC

MIXED, in ‘Proceedings of the 1993 Kansas State University Conference of

Applied Statistics in Agriculture’, pp. 40–59.

Milliken, G. A. & Johnson, D. E. (2002), Analysis of Messy Data, Volume III:

Analysis of Covariance, Chapman and Hall/CRC Press.

Oliver, D. S. (2003), ‘Gaussian Cosimulation: Modeling of the Cross-Covariance’,

Mathematical Geology 35, 681–698.

R Development Core Team (2004), R: A Language and Environment for Statistical

Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN

3-900051-07-0.

*http://www.R-project.org

Searle, S. R. (1971), Linear Models, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, United

States.

Stein, A. & Corsten, I. C. A. (1991), ‘Universal Kriging and Cokriging as a Regression Procedure’, Biometrics 47, 575–587.

Zimmerman, D. L. & Harville, D. A. (1991), ‘A Random Field Approach to the

Analysis of Field-Plot Experiments and other Spatial Experiments’, Biometrics 47, 223–239.

Revista Colombiana de Estadística 31 (2008) 95–109