Protein Quality Control Processes in the ...

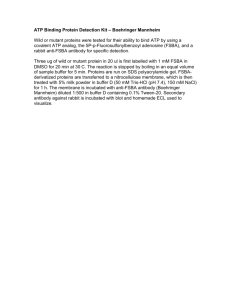

advertisement