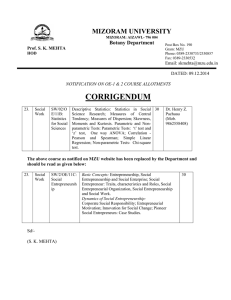

Entrepreneurship Policy for Entrepreneurs: Sarah Bird A by

advertisement