INTERCONNECTION PAYMENTS IN TELECOMMUNICATIONS A COMPETITIVE MARKET APPROACH David Gabel

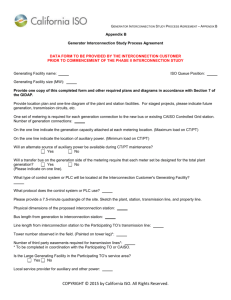

advertisement

INTERCONNECTION PAYMENTS IN TELECOMMUNICATIONS A COMPETITIVE MARKET APPROACH 1 David Gabel Introduction Telecommunications networks are unique because they require a high degree of cooperation from all parties involved and because of the interdependency of network components. Technical standards, service definitions, and pricing arrangements all must be well understood by the various users of the network in order to ensure efficient provision of the network’s services.2 Therefore, in order to allocate properly the joint costs and benefits of the telecommunications network, a sound interconnection pricing policy is of paramount importance. Establishing the price for interconnection, however, is a challenging undertaking, and there has been pressure on regulatory commissions to adopt interconnection arrangements that set termination charges at zero. This is due to the perception that regulators cannot measure costs correctly and have historically chosen interconnection prices that are too high.3 In addition, proponents of zero termination charges argue that the market distortions from high interconnection prices have induced new entrants in telecommunication services since 1996 to target firms, such as internet service providers (ISPs), that terminate large volumes of traffic. In this paper, we first discuss the concept of “Bill-and-Keep” whereby the party that receives a call pays for receiving the call. We explore if this outcome is efficient and consistent with competitive markets. Following the discussion of Bill-and-Keep we offer an explanation of w h y the flow of traffic has been imbalanced between incumbent local exchange carriers (ILECs) and competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs). We explain that this outcome is the natural outcome of the barriers to entry created by the incumbents in their refusal to provide collocation to internet service providers (ISPs). Interconnection Payments, Termination Charges, and Bill-and-Keep -- Setting the Correct Price Interconnection arrangements in the telecommunications industry have a long history. Interconnection first became a contractual issue in 1894 when Alexander Graham Bell’s initial patents expired. Beginning in 1894, the Bell System had to enter into interconnecting contracts with Independent telephone companies, and the Independents similarly signed contracts with each other that governed the terms of interconnection. 1 Professor of Economics, Queen College, City University of New York, and Visiting Scholar, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Internet and Telecommunications Convergence Consortium. 2 For a more complete discussion of telecommunication network characteristics, see Chapter 5, “Interconnection: Cornerstone of Competition” by William H. Melody in Telecom Reform: Principles, Policies, and Regulatory Practices, edited by William H. Melody, Den Private Ingeniorfond, Technical university of Denmark, Lyngby, 1997. 3 Patrick DeGraba, Federal Communications Commission, Office of Plans and Policy (OPP) Working Paper 33, “Bill-and-Keep at the Central Office as the Efficient Interconnection Regime”, Paragraphs 69, 91. 2 4 Bill-and-Keep, whereby there are no termination charges and each carrier is required to recover the costs of termination and origination from its own end-user customers, was adopted in certain situations in the past, but the most prevalent form of interconnection was revenue sharing. For example, the typical interconnection contract for a toll call required that fifteen to twenty-five percent of the originating revenue be paid to the terminating local exchange carrier.5 The contracts were established before the advent of federal or state regulation of the telephone industry, but the terms varied little after regulation was established. For local traffic, Bill-andKeep, was adopted where the traffic was balanced. Where the traffic was unbalanced, carriers relied on negotiated agreements between them governing either reciprocal compensation or access charges to recover the cost of interconnection. The originating party paid for the cost of interconnection under calling party pays arrangements, and where traffic was balanced under Bill-and-Keep. . Furthermore, the retail rates were generally designed so that the customers who initiated the calls paid for the calls, rather than having the cost of interconnection distributed evenly among the customers. This has been standard practice in the telecommunications industry on the basis that the decision made by an originating party to place a call is the decision that imposes costs on the network. The history of interconnection of telephone companies, illustrates: 1. The costs of interconnection have traditionally been recovered from the calling party on the basis that the calling party is the cost-causer; 2. The practice of calling party pays predates the establishment of state or federal regulation; and; 3. Bill-and-Keep has been adopted in situations where traffic is balanced -- where traffic is not balanced, the carrier on which the majority of traffic originated has made payments to the terminating carrier. Practical Constraints on Interconnection Pricing Arrangements In a world with no externalities (positive or negative) and perfect information interconnection pricing would be straightforward for regulators. In such a world, telephone service would represent a service for which two parties benefit, and that a call should be placed so long as the sum of the benefits exceeds the costs. At the margin, costs would be shared based on the benefits obtained by each party. In the real world, however, it is impossible to allocate the benefits to the calling and called parties, and thus it is problematic to ascertain how costs should be shared -- i.e., we cannot allocate costs on the basis of benefits because we do not know how to measure the benefits. Lacking information on valuation, the appropriate policy fallback is a second-best solution – using cost-based rates. Moreover, with the growth of competition in the telephone industry, it is even more important that prices must be established that govern the connection from one network to another. Regulators should be concerned that incumbent local exchange carriers (ILECs) will try to establish barriers to entry, and block entry by establishing too high of an interconnection price. Too avoid too high 4 Bill-and-Keep contracts were negotiated some of the time, but only where traffic was balanced. In those situations where traffic was out of balance, the company that originated the majority of the calls made a settlement payment. 5 David Gabel, “The Evolution of a Market: The Emergence of Regulation in the Telephone Industry of Wisconsin, 1893-1917,” Unpublished Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin—Madison, 1987, pp. 171-72. 3 of a price, regulators could impose a zero price on interconnection (i.e., Bill-and-Keep), but is this reasonable? We think not. Most other industries do not rely on Bill-and-Keep -- e.g., financial services, credit and ATM cards, package delivery services, and access fees for airport gates.6 In the telephone industry, we are now beginning to observe the operations of competitive markets at the start of the 21st century, and policy makers should not be enticed by simplistic and non-competitive zero-price solutions like Bill-and-Keep. The Distribution of Benefits from Phone Calls In this section we evaluate the proposition for Bill-and-Keep, and its policy implications. The strongest argument for Bill-and-Keep would be if the receiving party equally benefits from a call. This has been argued by some, but we disagree that the benefits of a telephone call are shared evenly by the caller and the receiver.7 Telephone calls are characterized by “joint demand” since there are at least two parties involved in any call.8 Similarly, the call is “jointly provided” by both the caller’s and the call receiver’s network. Consequently, the issue arises as to how to allocate joint costs. In a world with no externalities (positive or negative) and perfect information this would be straightforward since the parties would be expected to share the costs in proportion to the benefits they receive from the call. In the real world, however, it is impossible to allocate the benefits to the calling and called parties, and thus problematic to ascertain how costs should be shared. Since there are at least two parties to any telephone call, presumably both benefit from the call. Some experts have argued that this is justification for reversing the historical use of calling party pays, by shifting termination charges to the receiving party.9 However, even though call receivers benefit from SOME calls, it is impossible to say how the benefits of the call are shared, and therefore it is bad policy to assume that both parties benefit equally, and to base policy changes on this assumption. For example, calls from telemarketers surely benefit the caller more than the receiver, and many would argue that these calls have negative value for the receiver since he/she is likely not to be interested, and is interrupted in the middle of another activity. Proponents of mandatory Bill-and-Keep interconnection arrangements argue that callers make less calls since they must bear the entire costs of the call rather than sharing them with the receiver as would be the case under Bill-and-Keep arrangements.10 However, the fact that call receivers have the option of having toll-free numbers (e.g., like many businesses choose to do to encourage more business) suggests that call receivers have the option of purchasing a specific service which encourages them to receive more phone calls, and that the network is not 6 For a more complete discussion of the economics of networks and network pricing issues see The Economics of Network Industries by Oz Shy, Cambridge University Press, 2001. 7 Patrick DeGraba, Federal Communications Commission, Office of Plans and Policy (OPP) Working Paper 33, “Bill-and-Keep at the Central Office as the Efficient Interconnection Regime”, Paragraph 4. 8 Technically, joint demand occurs when a product is consumed simultaneously by more than one party (e.g. attendance at concerts and stadium events, use of highways and toll roads). 9 See, for example, Federal Communications Commission, Office of Plans and Policy Working Paper 33 by Patrick DeGraba, Bill and Keep at the Central Office as the Efficient Interconnection Regime. Federal Communications Commission, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking In the Matter of Developing a Unifie d Intercarrier Compensation Regime, CC Docket No. 01-92, April 27, 2001. 10 Allegiance Telecom -- In the Matter of Developing a Unified Intercarrier Compensation Regime, August 21, 2001 (CC Docket #01-92) -- Page 21 4 underutilized as suggested by proponents of mandatory Bill-and-Keep interconnection arrangements. There is no empirical evidence that callers would place more calls under Bill-and-Keep arrangements. Under toll-free services, the call receiver pays because it has decided that the benefits justify the additional costs incurred – whereas customers who choose not to have toll free numbers are implicitly saying that they benefit more by making phone calls than receiving them. Moreover, the proliferation of products to screen unwanted calls (e.g., Caller ID or Call Waiting) clearly contradicts the assumption under Bill-and-Keep that calling and called parties benefit equally from phone calls.11 Without these devices, only the calling party has complete information regarding the purpose of a telephone call, and thus it should bear the costs of termination. Since not all consumers can afford or desire call-screening devices, policy changes that unnecessarily encourage their purchase would be a costly technology distortion. This is not surprising because no empirical research on this issue would be meaningful since there is no way to measure the distribution of benefits between a caller, a receiver, and even a third party who benefits while not being part of the conversation. Interconnection policy should not be based on a hypothesis with no empirical foundation or support in the operations of unregulated competitive markets. Moreover, the case of network externalities below strongly supports the argument that the caller benefits more than the receiver, and a calling party pays system is more likely to capture these network externalities. In short, because we do not know the distribution of benefits on telephone calls, it is hard to conclude that Bill-and-Keep is efficient relative to reciprocal compensation. Furthermore, as discussed above, we know that in no other industry where traffic is out-of-balance do firms freely select Bill-and-Keep as a means for interconnection pricing. Interconnection and Network Externalities12 Using a Calling Party Pays system as opposed to Bill-and-Keep is more likely to internalize positive network externalities between calling and called parties, and is one of the main justifications for interconnection charges. Suppose that as a result of the called party being able and willing to accept a call, the calling party receives a direct benefit. This is an externality flowing from the called party to the calling party. Assuming, as is likely the case, this externality is larger compared to the externality going in the other direction (which would seem logical since the call was initiated by the caller who presumably has higher willingness to pay), then there may be efficiency grounds to have the calling party subsidize the called party. The incentive required to capture positive network externalities can be enacted through a termination charge since it encourages the receiving party to accept phone calls, whereas termination charges assessed on the receiving party will discourage the use of telephone services. A termination charge received by the terminating network will, through competition, be passed back to the called party by way of cheaper retail prices for services provided. If the calling party funds this termination charge, then this could be an efficient transfer between the two types of callers.13 However, by imposing mandatory Bill-and-Keep such transfers will be 11 Allegiance Telecom -- In the Matter of Developing a Unified Intercarrier Compensation Regime, August 21, 2001 (CC Docket #01-92) -- Page 21 12 This section draws on the work of Julian Wright of the Department of Economics at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. 13 An example where such network externalities are likely to be very important is the case of interconnection between fixed-line and mobile networks. Whereas mobile networks have penetration rates that are closer to 50%, a small decrease in the price offered to mobile customers can increase their participation and thereby provide a positive externality for existing fixed-line customers (and 5 eliminated. This will lead to serious inefficiencies where there are significant network externalities. Economic Efficiency Principles Under Bill-and-Keep, switching cost recovery would be folded into all of the other costs that must be recovered. The final rate would be either traffic-sensitive or a fixed per customer charge. However, if regulators cannot set traffic-sensitive rates correctly, as argued by the proponents of bill-and-keep, how can these costs be recovered efficiently? Having the user pay a per minute rate would discourage the use of telecommunications since there will be an incentive for parties to not answer calls to reduce termination charges assessed on them – i.e., Bill-and-Keep would not capture the positive network externalities associated with the Calling Party Network Pays principle. Per-minute charges also are not desirable for covering termination costs under the proposed Billand-Keep arrangements because they would “tip” the market towards monopoly since consumers would have an incentive to subscribe to larger and larger networks in order to avoid these charges. Any proposal to replace usage sensitive terminating access fees with a fixed customer charge contradicts the view that economic efficiency dictates that traffic sensitive costs be recovered through traffic sensitive rates. Aside from the argument that the cost-causer is not the costpayer, there are a number of reasons that Bill-and-Keep arrangements violate the principles of economic efficiency: ♦ Reforming the existing Calling Party’s Network Pays (CPNP) regimes with Bill-andKeep will require a reduction in per-minute charges to the caller and an increase in flat end-user charges to recover the lost revenue since the called parties’ providers would have no other way to recover termination costs except through flat-fees on its customers; ♦ A fixed monthly per-line subscriber charge ignores the capacity costs associated with termination of phone calls – all customers would pay the same fee for termination of calls regardless of the number of calls received; ♦ In unregulated markets Bill-and-Keep interconnection arrangements exist only under the restrictive condition of balanced traffic – however, in dynamic and partially regulated markets like telephones there is no guarantee that the traffic between any two operators will remain balanced over time and thus a Bill-andKeep arrangement does not afford adequate flexibility; and ♦ Under Bill-and-Keep and a fixed monthly subscriber line charge, the terminating company has less incentive to provide good service since it is not getting paid for the termination service on each call on a per call basis – there will be underinvestment in termination services and overinvestment in other services since recovering costs from a fixed monthly line subscriber charge does not send the proper signals on the cost of individual calls. networks). If the price of fixed-to-mobile calls is inflated and the higher price is used to subsidize low mobile subscription charges, the result can be an increase in welfare. Without providing this subsidy there would be less mobile customers. However, with fewer mobile customers, callers would have fewer options to call people who are away from their landline. Although a caller may be prepared to pay a high price to reach such people, the call will not be possible. 6 Bill-and-Keep amounts to setting termination charges at zero, which is clearly below cost since termination costs are non-zero. Setting the Price of Interconnection -- the Case of Collocation of Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and Competitive Local exchange carriers (CLECs) Traditionally interconnection pricing has been based on reciprocal compensation agreements reached between various local exchange companies (LECs). A new question that has recently arisen is what is the impact of traditional interconnection pricing arrangements on Internet service? Specifically, Internet Service Providers (ISPs) receive calls, but do not make calls. Consequently, some argue that this “one-way” traffic has led to a significant amount of money flowing away from incumbent local exchange carriers (ILECs) since the ISPs do not pay termination charges and have collocated facilities with competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs). On this basis, regulators have begun to rethink how to price interconnection, and to consider Billand-Keep interconnection pricing arrangements in order to force ISPs to cover termination costs.14 Under Bill-and-Keep, there are no reciprocal termination charges and each carrier is required to recover the costs of termination and origination from its own end-user customers. This paper argues that imposing mandatory Bill-and-Keep in order to correct for the ISP collocation “problem” is misguided and unsound. The ILECs claim that CLECs have targeted ISPs in order to take advantage of high reciprocal compensation rates. However, it is not a problem that CLECs have targeted ISPs as customers. There is an excellent reason why ISPs should all collocate with CLECs, and it has nothing to do with reciprocal compensation. ILECs have said enhanced service providers such as ISPs cannot collocate in their central offices. Therefore, ISPs can save a tremendous amount of money by collocating with CLECs, allowing them to avoid the costs of loops and transport for termination of modem pools back to the central office. Indeed, even if reciprocal compensation were priced at zero, because ILECs will not allow collocation of ISPs, it would still be a great opportunity to take business for CLECs. It should also come as no surprise that CLECs have targeted ISPs as customers. Since before the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 it has been well understood that fledgling LECs would, at least in the early stages of competition, primarily target businesses and other high margin telecommunications customers. Empirical evidence suggests that the Internet expanded rapidly around the same time the Telecommunications Act opened the door for competitors to provide local telecommunications services in 1996 -- with the percentage of households with internet access expanding from 17% to 42% from 1996-2000.15 The marketplace for ISPs expanded significantly at the same time that newly formed CLECs began searching for customers to serve. While ISPs are only one type of business customer, there is a fundamental difference between ISPs and other businesses that made their business more attractive to the CLECs. The CLECs may have had an easier time attracting an ISP’s business because there were no longstanding relationships with ILECs to overcome, and local number portability was not a concern. The ISP market was under-served by ILECs, and the CLECs attracted this business by offering state-of-the-art local fiber networks, and by offering 14 Federal Communications Commission, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking In the Matter of Developing a Unified Intercarrier Compensation Regime, CC Docket No. 01-92, April 27, 2001. 15 http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fttn00/charts00.html#f7 figure 1-1 7 16 to collocate ISP equipment. The beneficial relationship between CLECs and ISPs is clearly not a one-way street. CLECs and ISPs have become natural business associates because CLECs also provide certain synergies that are not present in the ILEC-ISP relationship. In order to avoid unnecessary switching and transport costs17 ISPs require the ability to aggregate Internet bound traffic in a facility that is collocated with a LEC’s facilities. Collocation allows the ISP to avoid the cost of first buying loops that carries dial-in traffic and then buying additional loops that carry the aggregated traffic back to the central office. The traffic needs to be returned to the central office in order to be shipped onto the Internet. Collocation is normally not offered to ISPs by ILECs because the FCC declined to require that ILECs make collocation space available to Enhanced Service Providers (“ESPs”).18 Without a specific mandate to provide collocation space, ILECs have demonstrated that they will not offer collocation to outside firms. Even with explicit instructions, the ILECs have shown a desire to deny or delay offering collocation facilities.19 Furthermore, ILECs do not have the same interest in competing with CLECs for ISP business, based on terms of collocation, because it would have a resounding impact on every rate the ILECs could charge for collocation facilities. It is apparent that the ILECs have made a conscious decision not to compete for the business of ISPs because it may well result in the ILECs having to offer collocation facilities at rates and terms that would encourage competitive entry into the ILECs core telecommunications markets. The ILECs would only be willing to create such barriers if they believe that the regulators will be willing to rescue them if a clever entrant finds away around the barrier. Regulators can improve the process of interconnection by holding parties to the terms of trade that they initially proposed. In the United States, the FCC has been too willing to accept the ISP traffic imbalance as a problem, rather than as an appropriate penalty imposed on an incumbent who created a barrier to entry and was unwilling to allow the efficient collocation of ISPs. As pointed out by the consulting firm Economics and Technology, “It would be entirely inappropriate at this time to now engage in what amounts to nothing short of a bail-out of those ILEC errors. In competitive markets, competitors live or die by their own business judgments and decisions, and it is 16 Focal Communications Corporation, Pac-West Telecommunications, RCN Telecom Services, and US LEC Corporation -- In the Matter of Developing a Unified Intercarrier Compensation Regime, August 21, 2001 (CC Docket #01-92) -- Pages 19-22 17 See: Connecting Homes to the Internet: An Engineering Cost Model of Cable vs. ISDN. Master Thesis of Sharon Eisner Gillett, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1995. “Notice that if the number of T1 lines into the Internet provider grows large enough, an economic incentive is created for the Internet provider to co-locate its facilities with a telephone company Central Office, to minimize distance-sensitive T1 tariffs.” at page 73; “The significant cost of the leased T1 lines needed to connect the Internet service provider to the local telephone network highlights another business and policy implication: ISDN Internet service would cost less to provide if these lines were not needed.” at page 152; “One way to eliminate (or reduce) these T1 line charges is to co-locate the Internet service provider with the local telephone company Central Office (just as the cable Internet service provider expects to co-locate with the cable head end). In that scenario, an external T1 circuit is replaced with an intra-office wire.” at page 153. The thesis is available at http://itel.mit.edu. 18 See: In the Matter of Implementation of the Local Competition Provisions of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, CC Docket No. 96-98, First Report and Order, FCC 96-325, Paragraph 581. 19 The ILECs have generally viewed collocation as an attack on their business. Wall Street Journal article August 9, 2001, titled “Covad Blames Its Recent Troubles On Bells' Anticompetitive Tactics” http://interactive.wsj.com/archive/retrieve.cgi?id=SB997325985752689883.djm. 8 not the role of regulators to backstop these market choices by after-the-fact protective measures.”20 Interconnection Pricing Arrangements should be Based on Capacity Charges We recognize that one problem with the current pricing of interconnection is that termination in the switch is based on a per minute charge with an equal charge on and off-peak. It would be more efficient to charge for interconnection in the manner which costs are incurred. On digital switching machines, incremental interconnection costs are incurred when the interoffice trunk is terminated. This costs is easily identifiable and this capacity cost should be the basis for setting rates. In the case of termination costs that are traffic sensitive, capacity charges are the most efficient recovery mechanism. Capacity charges are the best mechanism for recovering termination costs since the costs of terminating a call is determined by peak-usage. Provided that the capacity charges are based on forward-looking economic costs, they are an efficient means of recovering termination costs. Capacity charges are an effective and efficient way for one carrier to pay another for using the other carrier’s network. Yet, it would be virtually impossible to assess such charges directly on end users. Hence, it is reasonable -- and pro-competitive -- for each carrier to determine on its own how to recover the capacity charges from its customers. It is also important to point out that technological advances also argue in favor of more carrierpaid capacity-based charges rather than direct end-user charges. Packet switching is replacing circuit switching, and carriers are interconnecting with high-capacity links. Consequently, increased reliance on per-minute rates instead of capacity charges is nonsensical: “... as high capacity dedicated circuits become the norm, measuring traffic on a per-minute basis will be increasingly outmoded and unnecessary, as voice and data traffic will be indistinguishable. Accordingly, maintaining compensation structures that require measurement and compensation on a per-minute basis will impose unnecessary operational constraints and costs on carriers and equipment manufacturers.”21 The current tariffs for packet switching clearly illustrate that packet switching is offered on a capacity basis,22 and cost analysts are able to determine easily the cost of providing capacity on a packet switch system. There is no evidence that firms that interconnect packet switching networks rely on Bill-and-Keep. Therefore, the imposition of Bill-and-Keep would be contrary to the manner in which telecommunications pricing has evolved to reflect the cost structure of new technologies. 20 Economics and Technology, Inc. -- In the Matter of Developing a Unified Intercarrier Compensation Regime, August 21, 2001 (CC Docket #01-92) -- Page 27 21 Cbeyond -- In the Matter of Developing a Unified Intercarrier Compensation Regime, August 21, 2001 (CC Docket #01-92) -- Pages 5-6 22 See, for example, Qwest, “Interconnection and Collocation for Transport and Switched Unbundled Network Elements and Finished Services,” September 2001, at http://www.qwest.com/wholesale/downloads/2001/011017/77386_Issue_G_FD1.pdf, section 11; and “Verizon, Wireless Handbook, Exchange Access Frame Relay,” http://128.11.40.241/east/wholesale/wireless/wireless_handbook_7.7.htm. 9 Conclusion It is impossible to measure the “value” or “benefits” of a telephone call – especially for the party receiving the call. Value-laden policy decisions that have no empirical or theoretical basis are bad policy. The “cost-causer” pays approach is the most efficient approach to allocating costs since it avoids value-laden judgements about the benefits of phone calls and to whom they accrue. Moreover, the benefits of a call cannot be estimated before a call is made since one cannot possibly predict the precise “value” of a conversation. Interconnection payment schemes in the telecommunications industry therefore should be based on market forces and: ♦ Reflect the fact that the benefits of phone calls are not evenly distributed between callers and receivers; ♦ Capture the positive network externalities associated with the Calling Party Network Pays principle so as not to encourage the underutlization of telecommunications services; and ♦ Impose capacity charges that reflect traffic sensitive costs instead of using fixed end-user charges to recover termination costs. A one-fits-all interconnection pricing regime should not be used to cover the costs of interconnection of network traffic since this is not efficient in a market comprised of a variety of types of services, and which is very dynamic and innovative like telecommunications. Adopting such schemes to universally cover the costs of interconnection of network traffic is not sound policy since telecommunications networks are unique, require a high degree of cooperation from all parties involved, and because of the interdependency of network components. Cooperation is only economically efficient and conducive to competition when it is voluntary and contractual, and not imposed and mandatory as it would be under Bill-and-Keep interconnection pricing arrangements -- receiving no payment for handling traffic of rival firms would undermine competition in the telecommunications industry.