Read Chapter 7 – Prudent Practices; Read – Week 10, paper 1 – “Be careful what you In 1973 the EPA reported to Congress that there was a “clear and rapidly Summary 9

advertisement

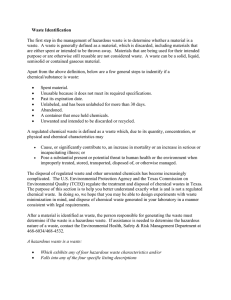

Summary 9 Read Chapter 7 – Prudent Practices; Read – Week 10, paper 1 – “Be careful what you call waste,” by Todd Houts; History ­ In 1973 the EPA reported to Congress that there was a “clear and rapidly growing hazardous waste management issue… that technologies were available to address the problem but adoption of these practices would add significant process costs and that existing economic or legislative incentives did not exist to encourage change toward better environmental management.” This report led to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) of 1976, a shift toward federal not local or state control of pollution. It is referred to as “cradle to grave” management of hazardous waste. RCRA was amended in 1984 to include smaller generators of hazardous waste, including small colleges and universities. Colleges and universities contribute about 1% of the nation’s total of hazardous waste. Certain waste was banned from landfills. Dr. Margaret­Ann Armour of the University of Alberta wrote an excellent book on treatment of laboratory waste: Hazardous Laboratory Chemicals Disposal Guide, 2 nd edition, Chelsea, Michigan; Lewis Publishers, Inc. 1996 The EPA is 11 entities with headquarters in 10 regional offices and DC. NY is in region 2. Regulatory Reform Spearheaded by Colleges and Universities The EPA is allowing a handful of colleges to operate under an alternate set of requirements based on an environmental management system. This is Project Lab­XL http://www.c2e2.org/labxl/ The Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Collaboratoive Hazardous Waste management Program reported college’s difficulty with EPA requirements: http://www.epa.gov/epaoswer/osw/specials/labwaste/ Semantically, it is better to refer to leftover chemicals as “unwanted materials” rather than waste. Then it can be reused, recycled, etc. Waste is put in a satellite accumulation area. Regulatory References ­ Federal Register – FR – published each business day – a history of a particular rule from proposal to codification. Ex. 69 FR 120 – would be page 120 in year 69 (2004) Code of Federal Regulations – CFR – the number preceding CFR refers to the specific code. Title 40 = protection of the environment; Title 49 = transportation; Title 29 = labor – this is where OSHA publishes worker protection rules. Following CFR is the sequential part then section. Ex. 29 CFR 1910.1450 is the regulation protecting lab workers from chemical use. The definition of hazardous waste in 40CFR261.3 is not scientifically correct – solid waste refers to solids, liquids and gases. Routes of Waste Disposal: (1) atmosphere – by evaporation or through the effluent from incineration; (2) water ­ via the sewer system and wastewater treatment facilities; and (3) landfills. 1 Characterization of Waste ­ Good labeling is important because it is usually straight foward to establish the hazardous characteristics of clearly identified waste. However, treatment disposal facilities are prohibited from accepting materials whose hazards are not known. The following is needed by treatment disposal facilities before they will consider handling unknown materials: · · · · · · · · · · · physical description – phase, color, consistency (solids), viscosity (liquids). water reactivity – determined by adding a small amount to H2O water solubility – measured – if insoluble does it sink or float? pH and possibly also neutralization information­pH is measured with pH paper ignitability (flammability)­ in an Al tray – if it burns after ½ second with a torch: flammable – if it burns after an additional 1 second with a torch:combustible presence of oxidizer ­ wet commercially available starch­iodide paper with 1 N hydrochloric acid, and then place a small portion of the unknown on the wetted paper. A change in color of the paper to dark purple is a positive test for an oxidizer. presence of sulfides or cyanides­. The test for inorganic sulfides or cyanides is carried out only when the pH of an aqueous solution of the unknown is greater than 10. For sulfides, add a few drops of concentrated hydrochloric acid to a sample of the unknown while holding a piece of commercial lead acetate paper, wetted with distilled water, over the sample. Development of a brown­black color on the paper indicates generation of hydrogen sulfide. For cyanides, 10% aqueous sodium hydroxide (solution A), 10% aqueous ferrous sulfate (solution B), and 5% ferric chloride (solution C). Mix 2 mL of the sample with 1 mL of distilled water and 1 mL each of solutions A, B, and C. Add enough concentrated sulfuric acid to make the solution acidic. Development of a blue color (Prussian blue, from ferric ferrocyanide) indicates cyanide. Because of the toxicity of the hydrogen cyanide formed during this test, only a small sample should be tested, and appropriate ventilation should be used. presence of halogens­A piece of copper wire is heated until red in a flame. The wire is cooled in distilled or deionized water, and then dipped into the unknown. The wire is again heated in the flame. A green color around the wire in the flame indicates halogens. presence of radioactive materials­use a Geiger counter presence of biohazardous materials­see Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (US DHHS 1993) presence of toxic constituents­ 2 FIGURE 7.1 Flow chart for categorizing unknown chemicals. This decision tree shows the sequence of tests that may need to be performed to determine the appropriate hazard category of an un known chemical. DWW, dangerous when wet; nos, not otherwise specified. 3 Regulated Chemical Hazardous Waste – defined by EPA under Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The danger depends on the composition and the quantity. EPA Characterization of Regulated Chemical Hazardous Waste 1. waste that has certain characteristics 2. waste that is on the EPA list of regulated chemicals Definitions of Characteristics Regulated Hazardous Waste: 1. Ignitability: Include most organic solvents, gases such as H2 and hydrocarbons and some nitrate salts: Characteristics a. Flashpoint less than 60C b. Non­liquid materials under standard temperature and pressure that can burn vigorously and persistently from friction, adsorption of moisture and spontaneous chemical changes 2. Corrosivity: liquids with a pH of 2 or less or 12.5 or greater 3. Reactivity: substances that are unstable, react violently with H2O, are capable of detonation if exposed to a detonation source, or produce toxic gases. Examples include alkali metals, peroxides, cyanides and sulfides. 4. Toxicity: if a toxic substance leaches from a substance under standard landfill conditions then the substance is considered toxic. Definitions of Listed Waste – Substances on one of the following lists – top 3 lists are of most interest to lab workers F list – hazardous waste from nonspecific sources P list – acutely toxic waste – LD50 of less than 50 mg/kg U list – toxic laboratory chemicals K list – hazardous waste from specific sources The waste generator must determine if the waste is hazardous and into what hazard classification it falls. Federal regulations allow the indefinite accumulation of up to 55 gallons of hazardous waste or 1 quart of acutely hazardous waste at or near the point of generation. Waste should not be held for more than a year. Rules for Satellite Accumulation Areas 1. Label all accumulation containers with the chemical contents and the hazard (flammable, corrosive, etc.) 4 2. Date all accumulation containers when you first add materials into the container 3. Keep containers closed except when actively adding materials 4. Make sure the container is compatible with the material being put into it and store in a secondary container to provide protection in case there is a spill of the container ruptures Central Accumulation Area – site where hazard reduction takes place. Combatible wastes from various sources are combined. This is a cost savings since disposal of a single 55 gallon drum is less expensive than disposal of many smaller vessels with the same total volume. Halogenated wastes are significantly more expensive to dispose of so halogenated and nonhalogenated are kept separate. Storage at a central accumulation area is limited to 90 days. The label must include the accumulation start date and the words, “Hazardous Waste.” The facility must include a fire suppression system, ventilation and dykes to avoid sewer contamination in the event of a spill. Waste often leaves in a Lab Pack, which is a container, frequently a 55 gal drum, in which small containers of waste are packed with an adsorbent material. The contents are sent to a disposal facility for incineration or treatment and disposal. Required Records 1. The quantity and identification of waste generated 2. Documentation of analysis of unknown materials 3. Manifests for shipping and verification of disposal. The waste generator retains the final responsibility for the long­term fate of the waste. 4. Any information required to insure compliace Hazard Reduction – important to be compliant – the fine for illegal treatment is up to $25,000 per day. Disposal Options: 1. Incineration: Advantage – minimum residue in landfills; long­term safety from liability Disadvantages: fewer incinerators being built (NIMBY) 2.Trash: more than commonly believed, including waste that is not regulated such as potassium chloride and sodium carbonate.. Verify safety for custodians 3. Sewer: Biodegradable and low toxicity inorganic aqueous solutions may be OK. Avoid water miscible flammable liquids and any water immiscible chemicals. 1ppm or less than 1% corrosives are also OK. 4. Atmosphere – evaporation in a fume hood is not acceptable. Disposal of Spills: spills less than 1 gallon that do not represent a fire or personal hazard can be cleaned up by lab workers. Once outside help is requested, specific personnel training requirements apply: Guidelines: 1. Realistically assess the situation and secure the area. Put up signs to keep people away. 5 2. If the spill is flammable, remove sources of ignition 3. Wear personal protective equipment – at a minimum protective gloves and goggles. Wear rubber boots if you may step in the spill. Wear a respirator if there is a danger from vapors. 4. Locate the spill kit and use adsorbent or other clean­up supplies as needed. Confine the spill so it doesn’t go down the sewer drain. Cover with adsorbent material. Neutraliz acids with sodium bicarbonate and bases with sodium bisulfate. Sweep up the adsorbed materials and dispose of in a closed container. Laboratory­Scale Treatment of Surplus and Waste Chemicals 1. Acids and bases – neutralize by co­mingling and dilute. If additional acid or base is needed use HCl, H2SO4 or NaOH, Mg(OH)2. The concentration of neutral salts in the sanitary sewer should be below 1%. 2. Thiols (SH) and sulfides (S) –destroy by oxidizing to sulfonic acid with NaClO 3. Acyl Halides (RCOX), sulfonyl halides (RSO2X) and Anhydrides (RCO)2O – avoid contact with water, alcohol and amines. Neutralize to low toxicity water soluble compounds with sodium hydroxide. 4. Aldehydes (RCHO) – generally use KMnO4 to oxidize to carboxylic acids which are less toxic and volatile. 5. Aromatic Amines (RNH2) – may be degraded by acidified potassium permanganate 6. Metal hydrides (MX) – react violently with H2O.: LiAlH4, KH and NaH are pyrophoric. May be decomposed by reacting with cooled alcohols in a hood. 7. Inorganic cyanides (MCN) – neutralization by NaOH followed by oxidation 8. Metal Azides (MN3) – explosive­ used in air bags – in drains can react with copper and explode. Silver azide and fulminate can be generated from Tollens reagent (used to make mirrors). Destroy in the hood with nitrous acid. 9. Alkali metals – react violently with water, hydroxylic solvents and halogenated hydrocarbons. Can be destroyed by alcohols. 10. Inorganic Ions – Precipitate and remove. Use table to determine acceptable pH range. 6