C21 Resources T

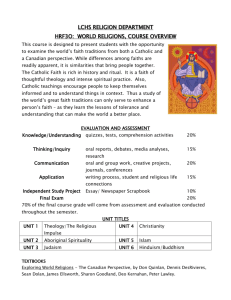

advertisement